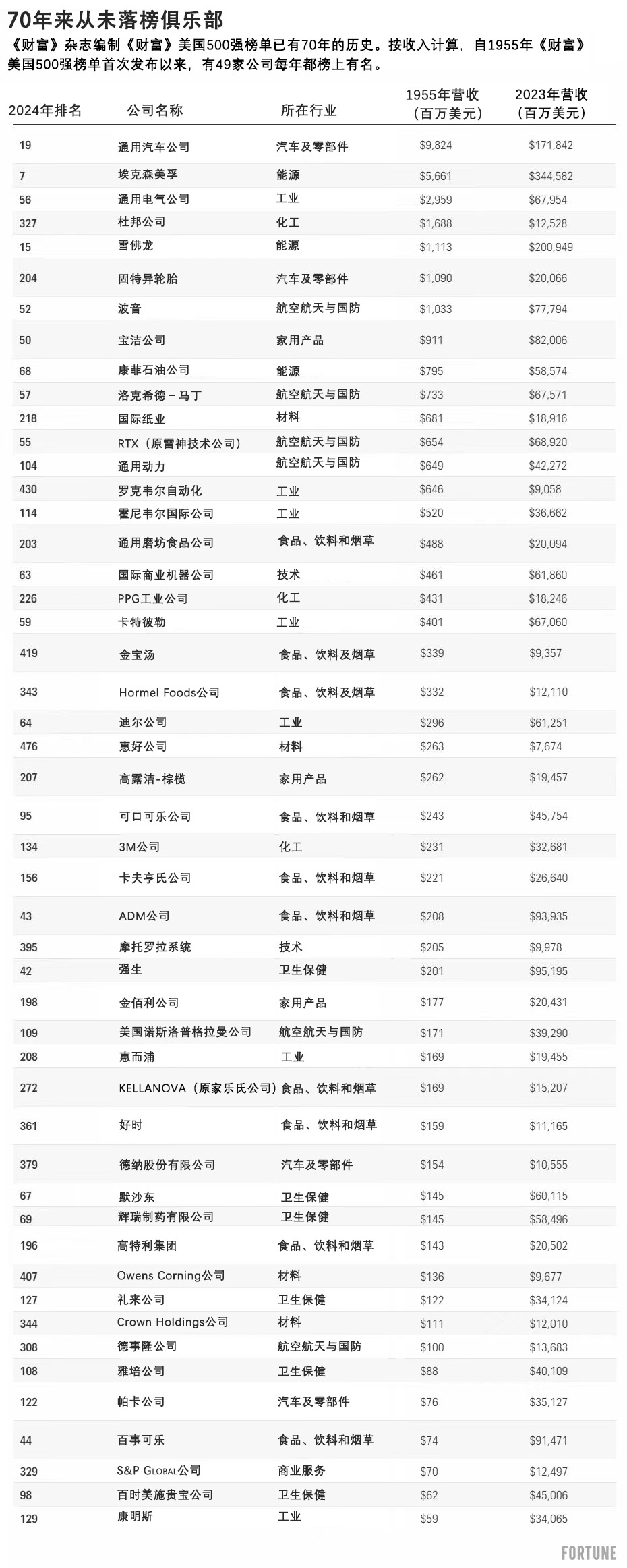

想想那些你所知道的最排外的組織——美國海豹第六特種部隊、《碧海黑帆》(Skull and Bones)游戲戰隊、奧古斯塔高爾夫俱樂部——而加入這些組織可能比躋身《財富》美國500強排行榜更容易。美國只有0.03%的公司能夠上榜,而且每家公司每年都必須重新獲得上榜資格,通常有幾十家公司無法上榜。如今,讓我們對美國公司萬神殿中一個更為獨特的俱樂部一探究竟。自1955年以來,數以千計的公司在《財富》美國500強排行榜中進進出出,只有49家公司在70次年度排名中每次都榜上有名。它們是美國企業界的奧運會選手。

這49家非同尋常的公司有什么不尋常的地方嗎?一項分析表明,早在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生之前,它們的魔力就開始發揮作用了。到那時,它們中的絕大多數已經發展壯大,躋身1955年第一屆榜單前列。我們應該注意的是,所有這些公司都是制造商或石油公司,原因是1955年的《財富》美國500強排行榜并不包括零售商、銀行、保險公司、公用事業和運輸供應商等服務公司(這些行業自1996年以來一直躋身排行榜)。此外,許多公司的歷史已經非常悠久——杜邦公司(DuPont)已有153年的歷史,高露潔-棕欖(Colgate-Palmolive)已有149年的歷史,迪爾公司(DEERE)和寶潔公司(PROCTER & GAMBLE)已有118年的歷史。在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生的數十年前,物競天擇已經將這49家公司中的大多數確定為商業界的紅杉。

但這并不能完全解釋為什么在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生之后的70年里,這49家公司能幸存下來并實現蓬勃發展。1955年上榜的許多其他歷史悠久的公司都已不復存在。達爾文式的類比可以給出更為全面的解釋,這49家公司無疑是適應性方面的冠軍,能夠靈活應對不斷變化的環境——是的,他們都能做到這一點。但仔細觀察就會發現,它們不同尋常的成功背后的基本要素卻略有不同。

關鍵洞察來自吉姆·柯林斯(Jim Collins)和杰里·波勒斯(Jerry Porras),他們是暢銷書《基業長青—企業永續經營的準則》(Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies)的作者。他們的整體研究成果于1994年首次出版,至今仍適用。他們選擇了一份“富有遠見的公司”名單,并將每家公司與同行業中表現良好、但不如“富有遠見的公司”表現優異的“對照公司”進行了分析。30年后的今天,17家躋身《財富》美國500強的富有遠見的公司全部仍榜上有名;只有6家“對照公司”上榜。

經過多年研究,柯林斯和波勒斯得出了幾條領軍者原則。最重要的原則是“保持核心競爭力,促進進步”,這也是這49家公司取得業績的核心要素。柯林斯后來撰寫了暢銷書《從優秀到卓越》(Good to Great)和《選擇卓越》(Great by Choice),他告訴《財富》雜志:“我越接受這個理論,就越覺得它可能是我有幸參與的數十年研究中最深刻的解釋性觀點。”

他們強調,一家公司的核心不是戰略、架構、技術,甚至不是文化。柯林斯說,隨著時間的推移,“所有這些東西都會發生變化”。核心是一家公司的基因,也是其存在的理由。柯林斯表示,他和波勒斯發現,與對照公司相比,富有遠見的公司“對核心價值的忠誠度要高得多,而且會清楚地意識到,他們的核心目標不僅僅是盈利。”這一核心的優點近年來引起了廣泛關注,但這不足為奇。這49家公司中的部分公司早在100或200年前就采用了這一理念。

這49家公司的首席執行官們用(柯林斯和波勒斯定義的)核心語言來解釋他們公司的長青之道——目的、價值觀、存在的理由。輝瑞制藥有限公司首席執行官阿爾伯特·布爾拉(Albert Bourla)告訴《財富》雜志:“輝瑞公司的存在是為了給患者帶來突破。”高露潔-棕欖首席執行官諾埃爾·華萊士(Noel Wallace)說,員工對“我們的目標”和“共同的價值觀”的承諾是公司取得長期業績的核心。禮來公司首席執行官戴文睿(David A. Ricks)表示:“禮來公司的長青之道源于我們的宗旨。”

成立于1902年的3M公司就是展示核心效力的典型例子。3M公司是富有遠見的“基業長青”公司之一,也是這49家公司之一。3M公司早期的設計師、長期領導人威廉·麥克奈特(William McKnight)認為,其公司的核心是發明。這是一個全新的概念——一家公司不是由行業、產品或服務定義的,而是由廣義的發明定義的。柯林斯說:“他只是認為創新是3M公司應該做的事情,原因是這是人類應該做的事情。”

3M公司的例子說明,為什么說適應性是這49家公司的制勝秘訣并不完全準確。適應是一種被動反應。每家公司都會面臨競爭,有時必須進行調整。但這49家公司大部分時間都在做其強大的核心驅動它們去做的事情,而世界也會反過來適應它們。想想強生公司發明大規模生產的無菌縫合線(1887年)、寶潔公司發明合成洗滌劑(1933年)或杜邦公司發明尼龍(1935年)等改變行業的進步。

這49家公司絕非完美無缺。它們并不是通過避免做出錯誤決定而獲得崇高聲譽的。這是不可能做到的。讓這些公司與眾不同的一大關鍵因素是它們從錯誤中恢復過來的卓越能力。想想可口可樂的歷史性錯誤“新可樂”(New Coke)吧:新可樂在1985年激怒了全美人民,這是前無古人后無來者的營銷策略。然而,在最近創下歷史新高的股價走勢圖上,這一失誤只是一個難以察覺的小插曲。這49家公司都經歷過類似的嚴重危機。

要了解這49家公司的與眾不同之處,一個很有啟發性的方法就是將它們與最初的《財富》美國500強中早已消失的企業巨頭進行比較。當時,排名第五的Swift meat company似乎是在500強排行榜中保持70年之久的有力候選者。該公司是一個龐然大物,比殼牌(Shell)和雪佛龍加起來還要大。此外,人們總是需要食物的,事實上,這49家公司中食品和飲料行業的公司確實比其他任何行業都多。但在20世紀60年代,Swift瘋狂擴張,不再局限于肉類,而是成為一家多元化的企業集團,業務涉及人壽保險、石油和女性內衣。這一策略并沒有奏效。經過多年被多家公司收購和出售,Swift現在只是世界上最大的肉類公司巴西JBS公司旗下的一個品牌。

從中吸取到的教訓是:Swift之所以跌出《財富》美國500強榜單,并不是因為它變成了一家企業集團。它之所以衰落,是因為成為一家企業集團并不是該公司的核心。集團化從來就不是其基因的一部分,這促使該公司無論如何都要實現多元化。相比之下,這49家公司之一德事隆公司躋身最初的《財富》美國500強時是一家企業集團,并一直保持至今。集團化是該公司的基因。

在世界最大經濟體的行業巔峰屹立70年之后,這49家公司的未來會怎樣?從理論上講,它們的業績表明這些公司應該能夠無限期地發展下去。但在現實生活中,大公司不會長青;這49家公司令人印象深刻的基業長青表明,它們都在預計期限之后繼續存在。

它們最好聽從亞馬遜(Amazon)創始人杰夫·貝索斯(Jeff Bezos)的現實主義建議。他在2018年的一次員工會議上說:“我預測有一天亞馬遜會失敗。亞馬遜會破產……我們必須盡量推遲那一天的到來。”要做到這一點,像這49家公司這樣杰出的公司面臨著極其隱蔽的自大威脅。自大是成功引起的,但也被成功所掩蓋,它將公司的重心轉向內部。起初,這種損害的累積速度很慢,但當這種損害到了顯而易見的時候,那就無法起死回生了。

對于這49家公司來說,抵御這種威脅是一個嚴峻的挑戰。這也是大多數其他公司都希望遇到的挑戰。(財富中文網)

譯者:中慧言-王芳

想想那些你所知道的最排外的組織——美國海豹第六特種部隊、《碧海黑帆》(Skull and Bones)游戲戰隊、奧古斯塔高爾夫俱樂部——而加入這些組織可能比躋身《財富》美國500強排行榜更容易。美國只有0.03%的公司能夠上榜,而且每家公司每年都必須重新獲得上榜資格,通常有幾十家公司無法上榜。如今,讓我們對美國公司萬神殿中一個更為獨特的俱樂部一探究竟。自1955年以來,數以千計的公司在《財富》美國500強排行榜中進進出出,只有49家公司在70次年度排名中每次都榜上有名。它們是美國企業界的奧運會選手。

這49家非同尋常的公司有什么不尋常的地方嗎?一項分析表明,早在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生之前,它們的魔力就開始發揮作用了。到那時,它們中的絕大多數已經發展壯大,躋身1955年第一屆榜單前列。我們應該注意的是,所有這些公司都是制造商或石油公司,原因是1955年的《財富》美國500強排行榜并不包括零售商、銀行、保險公司、公用事業和運輸供應商等服務公司(這些行業自1996年以來一直躋身排行榜)。此外,許多公司的歷史已經非常悠久——杜邦公司(DuPont)已有153年的歷史,高露潔-棕欖(Colgate-Palmolive)已有149年的歷史,迪爾公司(DEERE)和寶潔公司(PROCTER & GAMBLE)已有118年的歷史。在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生的數十年前,物競天擇已經將這49家公司中的大多數確定為商業界的紅杉。

但這并不能完全解釋為什么在《財富》美國500強第一屆榜單誕生之后的70年里,這49家公司能幸存下來并實現蓬勃發展。1955年上榜的許多其他歷史悠久的公司都已不復存在。達爾文式的類比可以給出更為全面的解釋,這49家公司無疑是適應性方面的冠軍,能夠靈活應對不斷變化的環境——是的,他們都能做到這一點。但仔細觀察就會發現,它們不同尋常的成功背后的基本要素卻略有不同。

關鍵洞察來自吉姆·柯林斯(Jim Collins)和杰里·波勒斯(Jerry Porras),他們是暢銷書《基業長青—企業永續經營的準則》(Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies)的作者。他們的整體研究成果于1994年首次出版,至今仍適用。他們選擇了一份“富有遠見的公司”名單,并將每家公司與同行業中表現良好、但不如“富有遠見的公司”表現優異的“對照公司”進行了分析。30年后的今天,17家躋身《財富》美國500強的富有遠見的公司全部仍榜上有名;只有6家“對照公司”上榜。

經過多年研究,柯林斯和波勒斯得出了幾條領軍者原則。最重要的原則是“保持核心競爭力,促進進步”,這也是這49家公司取得業績的核心要素。柯林斯后來撰寫了暢銷書《從優秀到卓越》(Good to Great)和《選擇卓越》(Great by Choice),他告訴《財富》雜志:“我越接受這個理論,就越覺得它可能是我有幸參與的數十年研究中最深刻的解釋性觀點。”

他們強調,一家公司的核心不是戰略、架構、技術,甚至不是文化。柯林斯說,隨著時間的推移,“所有這些東西都會發生變化”。核心是一家公司的基因,也是其存在的理由。柯林斯表示,他和波勒斯發現,與對照公司相比,富有遠見的公司“對核心價值的忠誠度要高得多,而且會清楚地意識到,他們的核心目標不僅僅是盈利。”這一核心的優點近年來引起了廣泛關注,但這不足為奇。這49家公司中的部分公司早在100或200年前就采用了這一理念。

這49家公司的首席執行官們用(柯林斯和波勒斯定義的)核心語言來解釋他們公司的長青之道——目的、價值觀、存在的理由。輝瑞制藥有限公司首席執行官阿爾伯特·布爾拉(Albert Bourla)告訴《財富》雜志:“輝瑞公司的存在是為了給患者帶來突破。”高露潔-棕欖首席執行官諾埃爾·華萊士(Noel Wallace)說,員工對“我們的目標”和“共同的價值觀”的承諾是公司取得長期業績的核心。禮來公司首席執行官戴文睿(David A. Ricks)表示:“禮來公司的長青之道源于我們的宗旨。”

成立于1902年的3M公司就是展示核心效力的典型例子。3M公司是富有遠見的“基業長青”公司之一,也是這49家公司之一。3M公司早期的設計師、長期領導人威廉·麥克奈特(William McKnight)認為,其公司的核心是發明。這是一個全新的概念——一家公司不是由行業、產品或服務定義的,而是由廣義的發明定義的。柯林斯說:“他只是認為創新是3M公司應該做的事情,原因是這是人類應該做的事情。”

3M公司的例子說明,為什么說適應性是這49家公司的制勝秘訣并不完全準確。適應是一種被動反應。每家公司都會面臨競爭,有時必須進行調整。但這49家公司大部分時間都在做其強大的核心驅動它們去做的事情,而世界也會反過來適應它們。想想強生公司發明大規模生產的無菌縫合線(1887年)、寶潔公司發明合成洗滌劑(1933年)或杜邦公司發明尼龍(1935年)等改變行業的進步。

這49家公司絕非完美無缺。它們并不是通過避免做出錯誤決定而獲得崇高聲譽的。這是不可能做到的。讓這些公司與眾不同的一大關鍵因素是它們從錯誤中恢復過來的卓越能力。想想可口可樂的歷史性錯誤“新可樂”(New Coke)吧:新可樂在1985年激怒了全美人民,這是前無古人后無來者的營銷策略。然而,在最近創下歷史新高的股價走勢圖上,這一失誤只是一個難以察覺的小插曲。這49家公司都經歷過類似的嚴重危機。

要了解這49家公司的與眾不同之處,一個很有啟發性的方法就是將它們與最初的《財富》美國500強中早已消失的企業巨頭進行比較。當時,排名第五的Swift meat company似乎是在500強排行榜中保持70年之久的有力候選者。該公司是一個龐然大物,比殼牌(Shell)和雪佛龍加起來還要大。此外,人們總是需要食物的,事實上,這49家公司中食品和飲料行業的公司確實比其他任何行業都多。但在20世紀60年代,Swift瘋狂擴張,不再局限于肉類,而是成為一家多元化的企業集團,業務涉及人壽保險、石油和女性內衣。這一策略并沒有奏效。經過多年被多家公司收購和出售,Swift現在只是世界上最大的肉類公司巴西JBS公司旗下的一個品牌。

從中吸取到的教訓是:Swift之所以跌出《財富》美國500強榜單,并不是因為它變成了一家企業集團。它之所以衰落,是因為成為一家企業集團并不是該公司的核心。集團化從來就不是其基因的一部分,這促使該公司無論如何都要實現多元化。相比之下,這49家公司之一德事隆公司躋身最初的《財富》美國500強時是一家企業集團,并一直保持至今。集團化是該公司的基因。

在世界最大經濟體的行業巔峰屹立70年之后,這49家公司的未來會怎樣?從理論上講,它們的業績表明這些公司應該能夠無限期地發展下去。但在現實生活中,大公司不會長青;這49家公司令人印象深刻的基業長青表明,它們都在預計期限之后繼續存在。

它們最好聽從亞馬遜(Amazon)創始人杰夫·貝索斯(Jeff Bezos)的現實主義建議。他在2018年的一次員工會議上說:“我預測有一天亞馬遜會失敗。亞馬遜會破產……我們必須盡量推遲那一天的到來。”要做到這一點,像這49家公司這樣杰出的公司面臨著極其隱蔽的自大威脅。自大是成功引起的,但也被成功所掩蓋,它將公司的重心轉向內部。起初,這種損害的累積速度很慢,但當這種損害到了顯而易見的時候,那就無法起死回生了。

對于這49家公司來說,抵御這種威脅是一個嚴峻的挑戰。這也是大多數其他公司都希望遇到的挑戰。(財富中文網)

譯者:中慧言-王芳

Think of the most exclusive groups you know—SEAL Team 6, Skull and Bones, Augusta National—and they’re probably easier to join than the Fortune 500. Only 0.03% of America’s incorporated companies make it, and each one must requalify every year; dozens of them typically don’t. Now, as we publish the 70th annual ranking of the Fortune 500, consider an even more exclusive club within this pantheon of U.S. companies. Of the thousands of firms that have come and gone in the 500 since 1955, only 49 have merited membership in every one of those 70 annual rankings. They are America’s corporate Olympians.

What have these extraordinary 49ers got? An analysis shows that their magic was at work long before the first Fortune 500. The vast majority of them had grown so large by then that they were in the top half of the 1955 ranking. We should note that all of them are manufacturers or oil companies because in 1955 the 500 did not include service companies such as retailers, banks, insurers, utilities, and transportation providers (those industries have been included since 1996). In addition, many were already uncommonly old—DuPont had been growing for 153 years, Colgate-Palmolive for 149 years, Deere and Procter & Gamble for 118 years. Decades before the Fortune 500 came along, natural selection had identified most of the 49ers as business sequoias.

But that doesn’t entirely explain why the 49ers have survived and thrived through the 70 years since that first 500. Plenty of the other old companies in 1955 are gone. As a fuller explanation, the Darwinian analogy suggests the 49ers must be champions of adaptability, nimbly responding to an ever-changing environment—and, yes, they can all do that. But a closer look shows that the fundamental factors in their unusual success are subtly different.

The key insight comes from Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, authors of the bestseller Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Their overall findings, first published in 1994, have held up remarkably well. They chose a list of “visionary companies” and analyzed each against a similar “comparison company” that was in the same industry and doing well, but not quite as well as the visionary company. Today, 30 years later, all 17 of their visionary companies that are eligible for the Fortune 500 are in the 500; only six of the comparison companies are.

After years of study, Collins and Porras derived several principles for leaders. The most important principle, and a central factor in our 49ers’ performance, was to “preserve the core and stimulate progress.” Collins, who later wrote the bestsellers Good to Great and Great by Choice, tells Fortune, “The more I live with it, the more I think it might be the deepest explanatory idea across all the multiple decades of research I’ve had the privilege to be involved in.”

A company’s core, they emphasized, isn’t strategies, structures, technologies, or even culture. Over time, “all that stuff is going to change,” Collins says. The core is a company’s DNA, its reason for being. Collins says he and Porras found that their visionary companies, when seen beside their comparison companies, “had a much deeper allegiance to their core values and a clear sense they had a core purpose beyond just making money.” The virtue of that foundation has attracted much attention in recent years, but it’s hardly new. Some of our 49ers adopted it 100 or 200 years ago.

Our 49ers’ CEOs explain their companies’ longevity in the language of the core as defined by Collins and Porras—purpose, values, reason for being. Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla tells Fortune, “Pfizer exists to deliver breakthroughs for patients.” Colgate-Palmolive CEO Noel Wallace says employee commitment to “our purpose” and “the values we share” is central to the company’s long-running performance. Eli Lilly CEO David A. Ricks says, “Lilly’s longevity is rooted in our purpose.”

A striking example of the core is 3M, founded in 1902. It’s one of the Built to Last visionary companies and one of our 49ers. Longtime leader William McKnight, 3M’s architect in the early days, believed the company’s core was inventing. That was a new concept—a company not defined by industry or products or services, but by inventing, broadly defined. “He just thought humans innovating is what 3M should be doing because that’s what humans should do,” Collins says.

3M’s example illustrates why it isn’t quite right to say adaptability is the essence of the 49ers. Adapting is reactive. Every company faces competition and must sometimes adapt. But the 49ers mostly do what their powerful core drives them to do, and the world adapts to them. Think of such industry-changing advances as Johnson & Johnson’s invention of mass-produced sterile sutures (1887) or Procter & Gamble’s invention of synthetic detergent (1933) or DuPont’s invention of nylon (1935).

The 49ers are by no means perfect. They didn’t attain their lofty reputations by avoiding bad decisions. That’s impossible. A key factor that sets those companies apart is their superior ability to recover from mistakes. Consider Coca-Cola’s New Coke, a historic blunder that in 1985 infuriated the nation like no other marketing strategy before or since. Yet today that snafu is an imperceptible blip on a stock price chart that recently hit all-time highs. All the 49ers have similarly come through grave crises.

An enlightening way to see what differentiates the 49ers is to compare them with long-gone corporate giants from the original Fortune 500. Back then, No. 5 on the list, the Swift meat company, would have seemed a strong candidate to stay in the 500 for 70 years. It was a colossus, bigger than Shell and Chevron combined. Besides, people will always need food, and indeed the 49ers include more companies from the food and beverage industry than from any other. But in the 1960s Swift expanded wildly beyond meat, becoming a diversified conglomerate with businesses in life insurance, petroleum, and women’s undergarments. It didn’t work. After years of being bought and sold by various firms, Swift is now only a brand owned by the Brazilian company JBS, the world’s largest meat company.

The lesson: Swift didn’t fall off the Fortune 500 because it became a conglomerate. It fell off because being a conglomerate wasn’t in its core. Conglomerating was never part of its DNA, pushing the company to diversify no matter what. By contrast, Textron, one of our 49ers, was a conglomerate when it landed on the original Fortune 500 and has remained one. Conglomerating is in its DNA.

After 70 years at the apex of industry in the world’s largest economy, what’s ahead for the 49ers? In theory, their performance says they should be able to carry on indefinitely. But in real life, big companies don’t live forever; the 49ers’ impressive longevity suggests they’re living on borrowed time.

They would probably be wise to follow Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s realist advice. “I predict one day Amazon will fail,” he told an employee meeting in 2018. “Amazon will go bankrupt… We have to try and delay that day for as long as possible.” To do that, companies as outstanding as the 49ers face the particularly insidious threat of hubris. Caused by success but also hidden by success, it turns the company’s focus inward. The damage accrues slowly at first. By the time it’s apparent, rescue may be impossible.

For the 49ers, fending off that threat is a serious problem. It’s a problem most other companies would love to have.