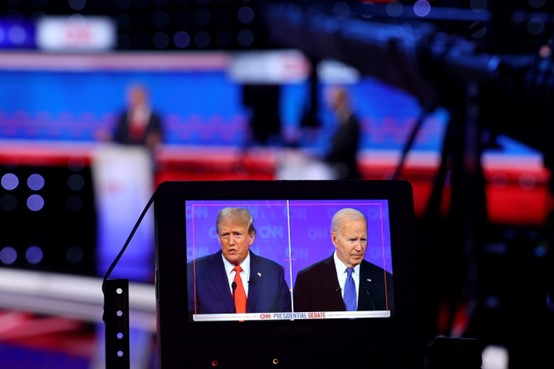

上周,時(shí)年78歲和81歲的候選人進(jìn)行了總統(tǒng)辯論,辯論結(jié)束后,大多數(shù)美國(guó)人都在思考年齡問(wèn)題。很多美國(guó)人都認(rèn)為總統(tǒng)拜登看起來(lái)"年老體弱",至少有一次公開(kāi)呼吁對(duì)其進(jìn)行認(rèn)知測(cè)試。

但是,年齡究竟會(huì)對(duì)大腦產(chǎn)生什么影響呢?《財(cái)富》雜志咨詢了衰老問(wèn)題專(zhuān)家,以更清楚地了解情況。

令人難以置信的大腦皮層萎縮

芝加哥大學(xué)(University of Chicago)神經(jīng)學(xué)教授、健康衰老與阿爾茨海默病研究護(hù)理中心主任艾米麗·羅加爾斯基(Emily Rogalski)告訴《財(cái)富》雜志:“隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),大腦會(huì)發(fā)生許多變化,其中之一就是我們所說(shuō)的大腦外層或皮層的萎縮。”

她解釋說(shuō),大腦皮層就像樹(shù)皮一樣,是腦細(xì)胞賴以生存的地方。

她說(shuō):"大腦皮層對(duì)我們的思考和交流非常重要。"大腦皮層的萎縮往往發(fā)生在與記憶有關(guān)的區(qū)域,而且往往與記憶變化相關(guān)。不管你是否相信,當(dāng)我們20多歲或30歲出頭的時(shí)候,記憶力會(huì)達(dá)到巔峰。

同樣容易受到影響的還有注意力和執(zhí)行能力。羅加爾斯基說(shuō):"所有這些能力在某種程度上都是相互關(guān)聯(lián)的,原因是你需要集中注意力才能記住事情。我們的認(rèn)知功能并不是孤立存在的。并不是說(shuō)大腦這片區(qū)域負(fù)責(zé)記憶,那片區(qū)域負(fù)責(zé)注意力,這些功能之間不進(jìn)行相互作用。大腦是一個(gè)復(fù)雜的系統(tǒng)。”

與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失是正常的

拉什大學(xué)(Rush University)精神病學(xué)和行為科學(xué)教授、拉什阿爾茨海默病中心神經(jīng)心理學(xué)家帕特麗夏·博伊爾(Patricia Boyle)指出,麥克奈特大腦研究基金會(huì)(McKnight Brain Research Foundation)最近的一項(xiàng)調(diào)查發(fā)現(xiàn),87%的美國(guó)人擔(dān)心隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),他們會(huì)經(jīng)歷與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失和大腦功能下降。

博伊爾告訴《財(cái)富》雜志:"但是,許多人不知道的是,與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失并不總是嚴(yán)重認(rèn)知問(wèn)題的征兆。大多數(shù)人都不明白,與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失通常與輕度健忘有關(guān),是大腦衰老的正常現(xiàn)象,并不一定是嚴(yán)重記憶問(wèn)題的征兆。"

她表示,正常衰老的跡象包括:

?偶爾做出錯(cuò)誤的決定

?忘記償還月供

?忘記時(shí)間

?找不到合適的措辭

?丟三落四

博伊爾說(shuō):“隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),出現(xiàn)認(rèn)知衰老的跡象是正常的,就像身體衰老的跡象是正常的一樣,比如行動(dòng)遲緩或疼痛加劇。”

隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),大腦萎縮確實(shí)會(huì)加速

隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),腦容量會(huì)不斷減少,包括負(fù)責(zé)認(rèn)知功能的前額葉和海馬體,到60歲左右,腦容量萎縮的速度會(huì)加快。

羅加爾斯基解釋說(shuō):"隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),我們罹患多種疾病的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)也隨之增加。”如果考慮到身體的磨損和脆弱性增加,而且事實(shí)上,不像臀部或膝蓋,大腦沒(méi)有替代品,就不難理解這一點(diǎn)了。

哥倫比亞大學(xué)梅爾曼公共衛(wèi)生學(xué)院(Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health)健康政策與衰老方面的教授約翰·羅(John Rowe)博士指出,衰老可能會(huì)導(dǎo)致兩種非典型認(rèn)知功能喪失中的一種:癡呆癥和輕度認(rèn)知障礙(MCI)。他說(shuō):“與年齡相關(guān)的變化發(fā)生在12%到18%的65歲以上老年人身上。在日常生活中反映出來(lái)的是,人們變得更加健忘、丟三落四、失約,而且這可能會(huì)影響日常生活。”他補(bǔ)充說(shuō),每年約有10%的輕度認(rèn)知障礙患者會(huì)發(fā)展為癡呆癥。

一些老年人表現(xiàn)出很高的水平

羅加爾斯基強(qiáng)調(diào),看待衰老的一個(gè)重要部分是,不要只糾結(jié)于那些出錯(cuò)的事情,還要關(guān)注新機(jī)會(huì)。“衰老帶來(lái)的巨大挑戰(zhàn)實(shí)際上是與衰老相關(guān)的污名,以及我們對(duì)老年人的期望(沒(méi)有向上的發(fā)展軌跡,只有不斷下降),我們不讓老年人參與活動(dòng),剝奪他們應(yīng)負(fù)的責(zé)任。”

她說(shuō),這也是一些新型豪華輔助生活設(shè)施存在的問(wèn)題,這些設(shè)施提供從客房服務(wù)到洗衣折疊等服務(wù)。"事實(shí)證明,我們所做的許多日常活動(dòng),如洗碗或四處走動(dòng),實(shí)際上對(duì)保持肌肉強(qiáng)健相當(dāng)有益。”同樣,讓大腦參與活動(dòng)和保持大腦活躍也很重要,有多種形式可以實(shí)現(xiàn)這一目的。"比如,保持社交聯(lián)系,學(xué)習(xí)新知識(shí)。但是,我們需要考慮如何鍛煉大腦和使用身體,包括考慮如何練習(xí)精細(xì)運(yùn)動(dòng)技能......如果我們不進(jìn)行這些活動(dòng),讓別人代勞,我們不一定會(huì)給自己帶來(lái)益處。"

不過(guò),羅強(qiáng)調(diào)說(shuō):“變化巨大。我們所看到的是,越來(lái)越多的人表現(xiàn)出很高的水平,他們?cè)谀撤N程度上是超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者。”

超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者登場(chǎng)了……

作為正在進(jìn)行的多學(xué)科“超級(jí)衰老研究計(jì)劃”的一部分,羅加爾斯基正在從生物學(xué)、家族史和生活方式的角度進(jìn)行研究,并尋找證據(jù),以了解是什么讓某些人看起來(lái)幾乎不會(huì)衰老,至少是在認(rèn)知水平上。

"我們發(fā)現(xiàn),從生物學(xué)角度看,'超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者'似乎與眾不同。他們的大腦實(shí)際上看起來(lái)更像五六十歲的老人,而不像八十歲的老人。"她說(shuō),并補(bǔ)充說(shuō),他們大腦的萎縮速度比普通八十歲老人要慢。

她說(shuō):“因此,他們似乎在抵制大腦外層或皮層變薄,當(dāng)我們使用極其精確的工具進(jìn)行測(cè)量時(shí)發(fā)現(xiàn),與50至60歲的老人相比,超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的大腦實(shí)際上并沒(méi)有表現(xiàn)出任何萎縮。”事實(shí)上,大腦中有一個(gè)叫做前扣帶回皮層(ACC)的區(qū)域(在動(dòng)機(jī)、決策、情緒和情境線索方面發(fā)揮作用)。超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的前扣帶回皮層比普通五六十歲老人的前扣帶回皮層更厚。他們還發(fā)現(xiàn)了大量被稱(chēng)為馮·艾克諾默神經(jīng)元的神經(jīng)元,使得科學(xué)家們找到了理解超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的“生物學(xué)路徑”。

羅告訴《財(cái)富》雜志,多年前,他在哈佛大學(xué)(Harvard University)管理著一個(gè)研究“成功衰老”的研究網(wǎng)絡(luò)。在一項(xiàng)研究中,他對(duì)一群75歲的老人進(jìn)行了長(zhǎng)達(dá)六年的跟蹤調(diào)查,在此期間對(duì)他們的身體和認(rèn)知能力進(jìn)行了測(cè)試。羅說(shuō):“研究結(jié)束時(shí),25%的人沒(méi)有變化,50%的人變得更糟糕,另一部分人則處于中間狀態(tài)。”他指出,那些表現(xiàn)最好的人,也就是超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者具有某些共同的生活方式特征,包括不獨(dú)居、受教育程度高和享有經(jīng)濟(jì)保障。

這表明,如果你今天召集一群80歲的老人來(lái)評(píng)估他們的認(rèn)知能力,你會(huì)得到好壞參半的結(jié)果:可能有一對(duì)夫婦患有癡呆癥,一兩個(gè)超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者,其他人則介于兩者之間。這不僅是由于人們的大腦變化速度不同,還與生活方式、遺傳和其他因素有關(guān)。

羅指出,他自己也已經(jīng)80歲了,他表示最重要的是,“我認(rèn)為,當(dāng)我們?cè)噲D將平均值簡(jiǎn)化為對(duì)某個(gè)個(gè)體的決定時(shí),談?wù)撈骄凳菦](méi)有任何意義的。我認(rèn)為我們不能把80歲老人的平均水平歸結(jié)為某個(gè)人的水平。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:中慧言-王芳

上周,時(shí)年78歲和81歲的候選人進(jìn)行了總統(tǒng)辯論,辯論結(jié)束后,大多數(shù)美國(guó)人都在思考年齡問(wèn)題。很多美國(guó)人都認(rèn)為總統(tǒng)拜登看起來(lái)"年老體弱",至少有一次公開(kāi)呼吁對(duì)其進(jìn)行認(rèn)知測(cè)試。

但是,年齡究竟會(huì)對(duì)大腦產(chǎn)生什么影響呢?《財(cái)富》雜志咨詢了衰老問(wèn)題專(zhuān)家,以更清楚地了解情況。

令人難以置信的大腦皮層萎縮

芝加哥大學(xué)(University of Chicago)神經(jīng)學(xué)教授、健康衰老與阿爾茨海默病研究護(hù)理中心主任艾米麗·羅加爾斯基(Emily Rogalski)告訴《財(cái)富》雜志:“隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),大腦會(huì)發(fā)生許多變化,其中之一就是我們所說(shuō)的大腦外層或皮層的萎縮。”

她解釋說(shuō),大腦皮層就像樹(shù)皮一樣,是腦細(xì)胞賴以生存的地方。

她說(shuō):"大腦皮層對(duì)我們的思考和交流非常重要。"大腦皮層的萎縮往往發(fā)生在與記憶有關(guān)的區(qū)域,而且往往與記憶變化相關(guān)。不管你是否相信,當(dāng)我們20多歲或30歲出頭的時(shí)候,記憶力會(huì)達(dá)到巔峰。

同樣容易受到影響的還有注意力和執(zhí)行能力。羅加爾斯基說(shuō):"所有這些能力在某種程度上都是相互關(guān)聯(lián)的,原因是你需要集中注意力才能記住事情。我們的認(rèn)知功能并不是孤立存在的。并不是說(shuō)大腦這片區(qū)域負(fù)責(zé)記憶,那片區(qū)域負(fù)責(zé)注意力,這些功能之間不進(jìn)行相互作用。大腦是一個(gè)復(fù)雜的系統(tǒng)。”

與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失是正常的

拉什大學(xué)(Rush University)精神病學(xué)和行為科學(xué)教授、拉什阿爾茨海默病中心神經(jīng)心理學(xué)家帕特麗夏·博伊爾(Patricia Boyle)指出,麥克奈特大腦研究基金會(huì)(McKnight Brain Research Foundation)最近的一項(xiàng)調(diào)查發(fā)現(xiàn),87%的美國(guó)人擔(dān)心隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),他們會(huì)經(jīng)歷與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失和大腦功能下降。

博伊爾告訴《財(cái)富》雜志:"但是,許多人不知道的是,與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失并不總是嚴(yán)重認(rèn)知問(wèn)題的征兆。大多數(shù)人都不明白,與年齡相關(guān)的記憶力喪失通常與輕度健忘有關(guān),是大腦衰老的正常現(xiàn)象,并不一定是嚴(yán)重記憶問(wèn)題的征兆。"

她表示,正常衰老的跡象包括:

?偶爾做出錯(cuò)誤的決定

?忘記償還月供

?忘記時(shí)間

?找不到合適的措辭

?丟三落四

博伊爾說(shuō):“隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),出現(xiàn)認(rèn)知衰老的跡象是正常的,就像身體衰老的跡象是正常的一樣,比如行動(dòng)遲緩或疼痛加劇。”

隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),大腦萎縮確實(shí)會(huì)加速

隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),腦容量會(huì)不斷減少,包括負(fù)責(zé)認(rèn)知功能的前額葉和海馬體,到60歲左右,腦容量萎縮的速度會(huì)加快。

羅加爾斯基解釋說(shuō):"隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),我們罹患多種疾病的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)也隨之增加。”如果考慮到身體的磨損和脆弱性增加,而且事實(shí)上,不像臀部或膝蓋,大腦沒(méi)有替代品,就不難理解這一點(diǎn)了。

哥倫比亞大學(xué)梅爾曼公共衛(wèi)生學(xué)院(Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health)健康政策與衰老方面的教授約翰·羅(John Rowe)博士指出,衰老可能會(huì)導(dǎo)致兩種非典型認(rèn)知功能喪失中的一種:癡呆癥和輕度認(rèn)知障礙(MCI)。他說(shuō):“與年齡相關(guān)的變化發(fā)生在12%到18%的65歲以上老年人身上。在日常生活中反映出來(lái)的是,人們變得更加健忘、丟三落四、失約,而且這可能會(huì)影響日常生活。”他補(bǔ)充說(shuō),每年約有10%的輕度認(rèn)知障礙患者會(huì)發(fā)展為癡呆癥。

一些老年人表現(xiàn)出很高的水平

羅加爾斯基強(qiáng)調(diào),看待衰老的一個(gè)重要部分是,不要只糾結(jié)于那些出錯(cuò)的事情,還要關(guān)注新機(jī)會(huì)。“衰老帶來(lái)的巨大挑戰(zhàn)實(shí)際上是與衰老相關(guān)的污名,以及我們對(duì)老年人的期望(沒(méi)有向上的發(fā)展軌跡,只有不斷下降),我們不讓老年人參與活動(dòng),剝奪他們應(yīng)負(fù)的責(zé)任。”

她說(shuō),這也是一些新型豪華輔助生活設(shè)施存在的問(wèn)題,這些設(shè)施提供從客房服務(wù)到洗衣折疊等服務(wù)。"事實(shí)證明,我們所做的許多日常活動(dòng),如洗碗或四處走動(dòng),實(shí)際上對(duì)保持肌肉強(qiáng)健相當(dāng)有益。”同樣,讓大腦參與活動(dòng)和保持大腦活躍也很重要,有多種形式可以實(shí)現(xiàn)這一目的。"比如,保持社交聯(lián)系,學(xué)習(xí)新知識(shí)。但是,我們需要考慮如何鍛煉大腦和使用身體,包括考慮如何練習(xí)精細(xì)運(yùn)動(dòng)技能......如果我們不進(jìn)行這些活動(dòng),讓別人代勞,我們不一定會(huì)給自己帶來(lái)益處。"

不過(guò),羅強(qiáng)調(diào)說(shuō):“變化巨大。我們所看到的是,越來(lái)越多的人表現(xiàn)出很高的水平,他們?cè)谀撤N程度上是超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者。”

超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者登場(chǎng)了……

作為正在進(jìn)行的多學(xué)科“超級(jí)衰老研究計(jì)劃”的一部分,羅加爾斯基正在從生物學(xué)、家族史和生活方式的角度進(jìn)行研究,并尋找證據(jù),以了解是什么讓某些人看起來(lái)幾乎不會(huì)衰老,至少是在認(rèn)知水平上。

"我們發(fā)現(xiàn),從生物學(xué)角度看,'超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者'似乎與眾不同。他們的大腦實(shí)際上看起來(lái)更像五六十歲的老人,而不像八十歲的老人。"她說(shuō),并補(bǔ)充說(shuō),他們大腦的萎縮速度比普通八十歲老人要慢。

她說(shuō):“因此,他們似乎在抵制大腦外層或皮層變薄,當(dāng)我們使用極其精確的工具進(jìn)行測(cè)量時(shí)發(fā)現(xiàn),與50至60歲的老人相比,超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的大腦實(shí)際上并沒(méi)有表現(xiàn)出任何萎縮。”事實(shí)上,大腦中有一個(gè)叫做前扣帶回皮層(ACC)的區(qū)域(在動(dòng)機(jī)、決策、情緒和情境線索方面發(fā)揮作用)。超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的前扣帶回皮層比普通五六十歲老人的前扣帶回皮層更厚。他們還發(fā)現(xiàn)了大量被稱(chēng)為馮·艾克諾默神經(jīng)元的神經(jīng)元,使得科學(xué)家們找到了理解超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者的“生物學(xué)路徑”。

羅告訴《財(cái)富》雜志,多年前,他在哈佛大學(xué)(Harvard University)管理著一個(gè)研究“成功衰老”的研究網(wǎng)絡(luò)。在一項(xiàng)研究中,他對(duì)一群75歲的老人進(jìn)行了長(zhǎng)達(dá)六年的跟蹤調(diào)查,在此期間對(duì)他們的身體和認(rèn)知能力進(jìn)行了測(cè)試。羅說(shuō):“研究結(jié)束時(shí),25%的人沒(méi)有變化,50%的人變得更糟糕,另一部分人則處于中間狀態(tài)。”他指出,那些表現(xiàn)最好的人,也就是超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者具有某些共同的生活方式特征,包括不獨(dú)居、受教育程度高和享有經(jīng)濟(jì)保障。

這表明,如果你今天召集一群80歲的老人來(lái)評(píng)估他們的認(rèn)知能力,你會(huì)得到好壞參半的結(jié)果:可能有一對(duì)夫婦患有癡呆癥,一兩個(gè)超級(jí)長(zhǎng)者,其他人則介于兩者之間。這不僅是由于人們的大腦變化速度不同,還與生活方式、遺傳和其他因素有關(guān)。

羅指出,他自己也已經(jīng)80歲了,他表示最重要的是,“我認(rèn)為,當(dāng)我們?cè)噲D將平均值簡(jiǎn)化為對(duì)某個(gè)個(gè)體的決定時(shí),談?wù)撈骄凳菦](méi)有任何意義的。我認(rèn)為我們不能把80歲老人的平均水平歸結(jié)為某個(gè)人的水平。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:中慧言-王芳

In the wake of last week’s presidential debate between the 78- and 81-year-old candidates—and the impression among some that President Joe Biden looked “old and frail,” with at least one public call for cognitive testing—much of America has had age on the brain.

But what does age actually do to the brain? Fortune consulted with experts on aging to get a clearer picture.

The incredible shrinking cortex

“The brain undergoes many changes associated with aging, and one of them is the shrinkage of what we call the outer layer of the brain, or the cortex,” Emily Rogalski, professor of neurology at the University of Chicago and director of its Healthy Aging & Alzheimer’s Research Care Center, tells Fortune.

The cortex, she explains, is like the bark on a tree, and is the layer where brain cells live.

“It’s really important to our thinking and our communication,” she says, and its shrinking tends to occur in areas related to memory, and tends to be correlated with changes in memory—which is at its peak performance, believe it or not, when we are just in our 20s or early 30s.

Also vulnerable as a result are skills of attention and executive functioning. “And all of these things are interrelated in a way, because you need to have good attention in order to remember something,” Rogalski says. “Our cognitive functions don’t just sit on little islands of, here’s memory and here’s attention, and there’s no interaction. It’s a complex system.”

Age-related memory loss is normal

A recent McKnight Brain Research Foundation survey, points out Patricia Boyle, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Rush University and a neuropsychologist with the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, found that 87% of Americans are concerned about experiencing age-related memory loss and a decline in brain function as they grow older.

“But, what many don’t know is that age-related memory loss is not always a sign of a serious cognitive problem,” Boyle tells Fortune. “Most people do not understand that age-related memory loss is usually associated with mild forgetfulness and is a normal part of brain aging and not necessarily a sign of a serious memory problem.”

Some signs of normal aging, she says, include:

? Making a bad decision occasionally

? Missing a monthly payment

? Losing track of time

? Not being able to find the right words

? Losing things around the house

“As we get older, it is normal to see signs of cognitive aging just like it’s normal to see the physical signs of your body aging, like moving slower or more aches and pains,” Boyle says.

Brain shrinkage does accelerate when you’re older

Brain volume continues to decrease as we age—including the frontal lobe and hippocampus, the areas responsible for cognitive functions—with the rate of shrinkage increasing by around age 60.

“With aging, we increase our risk for many diseases just by getting older,” which makes sense, Rogalski explains, if you think about wear and tear and the increasing vulnerabilities of our body—and the fact that, unlike with hips or knees, there are no brain replacements.

Aging brings the possibility of one of two types of atypical loss of cognitive function, notes Dr. John Rowe, a Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health professor of health policy and aging: dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), “an age-related change that occurs in between 12% and 18% of older people, over 65,” he says. “And what is reflected in day-to-day living is that people become more forgetful, they lose things, they miss appointments, and this can have an impact on your day-to-day function.” MCI, he adds, progresses to dementia in about 10% of people per year.

Some older adults are performing at high levels

Rogalski stresses that an important part of looking at aging is to not just dwell on the things that go wrong, but new opportunities. “A huge challenge with aging is actually the stigma associated with aging and the expectations that we put on individuals as they age—that there is no trajectory but down—and that we take away activities and responsibilities that people can do.”

And that’s a problem in some new, luxury assisted-living facilities, she says, which provide services from room service to laundry folding. “It turns out that many of these daily activities that we do, such as washing our dishes or just moving around, are actually really good for keeping those muscles strong.” Similarly, it’s important to keep our brain engaged and active, which can come in many forms. “It can come from staying socially connected. It can come from learning something new. But we want to think about exercising our brain and using our body, including thinking about ways to practice our fine motor skills … and if we have those things taken away and done for us, we’re not necessarily doing ourselves a service.”

Still, stresses Rowe, “There’s tremendous variability. And what we’re seeing is an increasing proportion of the older population that’s performing at very high levels who are kind of superagers.”

Enter the superagers…

Rogalski, through her research as part of the ongoing, multidisciplinary SuperAging Research Initiative, is looking at evidence from biologic, family history and lifestyle perspectives in order to learn what makes certain people seem to barely age, at least cognitively.

“What we’ve seen is that superagers, biologically, seem to look different. Their brains actually look more like 50 to 60 year olds than they do like 80 year olds,” she says, adding that their rate of shrinkage is slower than that of average 80-year-olds.

“So they seem to be resisting that thinning of the outer layer of the brain, or the cortex, and when we measure it using really precise tools, we see that the superager brains actually don’t show any shrinkage relative to the 50- to 60-year-olds,” she says. In fact, there’s a region of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)—which has a role in motivation, decision-making, and emotional and situational cues—that’s thicker in the superagers than it is in the 50- to 60-year-olds. They’ve also discovered an abundance of a neuron called von Economo neurons, helping scientists to have a “biologic pathway” for understanding superagers.

Years ago, Rowe tells Fortune, he ran a research network that studied “successful aging” at Harvard University. In one study, he followed a group of 75-year-olds for six years, testing them physically and cognitively over that period. “At the end, 25% had not changed, 50% had gotten much worse and the other kind of stayed in the middle,” says Rowe, noting that those who did the best, the superagers, shared certain lifestyle characteristics, including not living alone, educational attainment, and financial security.

It underscores how, were you to gather a bunch of 80-year-olds today to assess their cognitively abilities, you’d get mixed results: Probably a couple with dementia, a superager or two, and others who are in between. That’s not only due to people’s brains changing at different rates, but also the difference in lifestyles, genetics, and other factors.

Bottom line, says Rowe, who points out that he himself is 80, “I don’t think we can talk about an average with any meaningful validity when we are trying to reduce that to a decision about a person. I don’t think we can ascribe an average of an 80-year-old to an individual.”