2000年1月的一天,斯坦福大學(Stanford University)一位名叫保羅·馬丁的年輕學生走進了位于美國帕洛阿爾托市的大學大道(University Avenue)的Confinity 初創科技公司。他是為了一份實習工作來找彼得·蒂爾的。

蒂爾當時還沒有成為著名的創始人和投資人,但他的面孔并不陌生,這要歸功于蒂爾為《斯坦福評論》(Stanford Review)的員工舉辦的一次次晚宴。《斯坦福評論》是斯坦福大學校內的一份保守派學生報紙,蒂爾在本科學習哲學專業時與他人共同創辦了這份報紙。在帕洛阿爾托的一家牛排館舉行的某次晚宴中,蒂爾給當時擔任報紙業務經理的馬丁留下了深刻印象。馬丁記得那次晚宴討論的話題涉獵很廣,從宗教到政治,從經濟到娛樂。

馬丁說:“他是一個令人印象深刻的人。如果他說:‘嘿,我有一家公司,我認為它很有可能取得巨大成功。’那么你就會[想]:‘也許我應該加入這家公司。’”

當馬丁到達Confinity公司時,他驚訝地發現《斯坦福評論》的另一位員工已經在Confinity工作了——那就是埃里克·杰克遜,他曾經在馬丁讀大一的時候擔任過報紙的主編。馬丁與蒂爾談話結束后,杰克遜帶著這位本科生去吃午飯,就在大學大道的街邊小店。馬丁回憶道:“他說:‘你知道嗎,這里正在起飛,我們一定會干出一番事情。如果你現在加入,你就會成為偉大事業的一部分。可你如果猶豫,機會就將消失。’”

不久,馬丁從斯坦福大學退學,也退出了學校田徑隊,開始在Confinity公司全職工作。這家公司最終更名為PayPal。

當時追隨彼得·蒂爾的有好幾十號人,馬丁和杰克遜只是其中之二。這里的工作已經悄然成為硅谷最令人羨慕的通往成功的途徑。這一切都始于《斯坦福評論》——1987 年,蒂爾與另一位未來的PayPal的早期員工諾曼·布克共同創辦的這份學生報紙。

蒂爾說:“我們在1987年創辦《斯坦福評論》時,顯然沒有料到幾十年后它會成為硅谷的一個令人難以置信的科技圈子。”他同意接受《財富》雜志的采訪,討論這份報紙。(與蒂爾一起通話的還有薩姆·沃爾夫,他是2018-19年度的前主編,通過《斯坦福評論》認識了蒂爾,目前在蒂爾的對沖基金擔任研究員。)

蒂爾在采訪中說:“我們在思想上當然并不完全一致,但我們有很多緊密的個人聯系,不僅是我和大家的聯系,還有他們互相之間的聯系——這就形成了一種團隊精神,對我們幫助很大……[PayPal]當然也經歷了很多波折和起伏——這種緊密的友情對我們共同度過公司的起起落落非常有幫助。”

在校園里,這份保守派的學生報紙在其30多年的歷史中曾經因為激怒左傾的斯坦福社區而聞名。每隔一段時間,《斯坦福評論》的某一篇慷慨激昂、引發爭議的評論文章就會登上全國頭條,這些文章或抨擊政治正確,或反對同性戀,或批評斯坦福大學的某位教授。包括一些《斯坦福評論》撰稿人在內的斯坦福學生在20世紀90年代對該校提起了訴訟,最終推動該校撤銷了禁止校園內激烈言論的規定。不過,除了少數幾個廣受關注的事件之外,該報在斯坦福校園之外基本上一直默默無名,即使其圈子已經擴大到相當規模的程度。

《斯坦福評論》的前編輯們說,早在蒂爾于1989年從斯坦福大學獲得本科學位后,他就一直在培養報紙的社區影響力。蒂爾至今仍然在參與這份報紙的工作。30多年來,他一直在家中或帕洛阿爾托的圣丹斯牛排館(Sundance steak house)等地為員工舉辦晚宴,討論世界大事和政治哲學問題,并向學生們了解大學生活和校園中的思潮。2017年,《斯坦福評論》為校友們舉辦了30周年聚會,現任主編沃克·斯圖爾特告訴《財富》雜志,就在去年,他還參加了蒂爾為報紙撰稿人舉辦的晚宴。

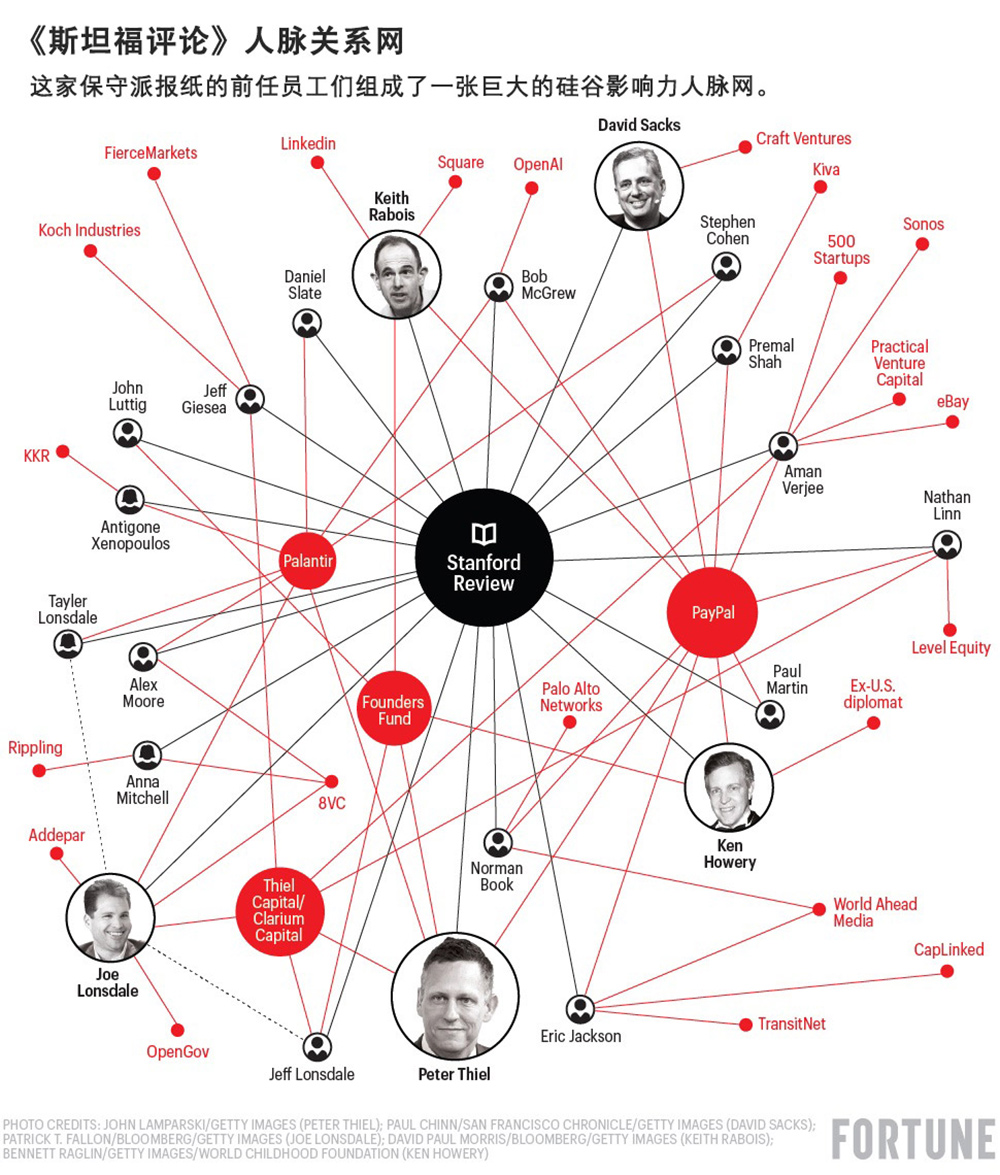

回顧一下《斯坦福評論》的歷史刊頭,就會發現這位傳奇投資人的圈子是多么龐大,多么緊密。PayPal的幾位聯合創始人或早期高管——蒂爾、Craft Ventures的大衛·薩克斯和美國駐瑞典前大使肯·霍威利——都曾經為該報撰稿。撰稿人還包括Palantir的三位創始人,該公司是一家國防技術公司,截至8月中旬市值接近330億美元。此外,還有Founders Fund的投資人基思·拉布瓦和Founders Fund的負責人約翰·呂蒂希,前者曾經在LinkedIn和Square任職。喬·朗斯代爾在擔任《斯坦福評論》主編后曾經為蒂爾工作,現在經營著風險投資公司8VC,他聘用了許多這家保守派報紙的員工,包括與他共同投資時間最長的合伙人之一亞歷克斯·穆爾,以及去年剛從斯坦福大學畢業的馬克斯韋爾·邁耶。(朗斯代爾與《斯坦福評論》的另一位編輯泰勒·考克斯組建了家庭,朗斯代爾的兄弟也曾經為該報撰稿。)

根據彭博億萬富豪指數(Bloomberg Billionaires Index),曾經在美國前總統唐納德·特朗普的過渡委員會任職的蒂爾本人的身價約為93億美元。這群校友在風險投資基金和科技公司方面的總資產是這一數字的好幾倍。Founders Fund上一次公布的資產管理規模為110億美元,朗斯代爾的8VC管理著超過60億美元的承諾資金,更不用說《斯坦福評論》的校友們已經在整個行業的科技公司中發揮了影響力。例如,《斯坦福評論》的前業務經理吉迪恩·于曾經在Facebook(現在的Meta)擔任過兩年的首席財務官,又比如《斯坦福評論》的校友鮑勃·麥格魯目前在OpenAI擔任研究副總裁。

六年前,前斯坦福大學學生安德魯·格拉納托花了將近一年的時間,仔細分析了《斯坦福評論》龐大的人脈網絡,并在學生雜志《斯坦福政治》(Stanford Politics)上發表的一篇文章,指出有近300名參與過《斯坦福評論》的校友曾經為蒂爾或朗斯代爾工作,或接受過他們的投資。自2018年以來,這些數字還在繼續上升。《財富》雜志發現,至少還有六人在Palantir、蒂爾資本、Founders Fund、蒂爾基金會(Thiel Capital)或朗斯代爾的風險投資基金8VC實習或工作,還有一些人在Founders Fund支持的Rippling等公司工作。

《財富》雜志采訪了包括蒂爾在內的10位現任或前任《斯坦福評論》編輯和工作人員,查閱了數百頁的非營利性文件,以及廣泛的公司網站、LinkedIn網頁和存檔的報紙文章,以了解這份學生報紙是如何成為硅谷科技生態系統中如此顯赫但又飽受爭議的平臺——還有將這群人聯系在一起的共同點。(其中兩人在匿名的情況下接受了《財富》雜志的采訪,一人要求保密,以便討論報紙上一些有爭議的文章。)

“現在回頭看,這份報紙是我職業生涯中非常重要的組成部分。”杰克遜說。他是《斯坦福評論》的編輯,也是PayPal的早期員工,后來與《斯坦福評論》的聯合創始人諾曼·布克一起成立了一家以保守派和基督教市場為重點的出版公司,并撰寫了一本關于PayPal的書。杰克遜說,他招募了《斯坦福評論》的校友,向他們尋求投資,并讓他們擔任自己多年來創辦的科技初創公司的顧問和董事。

《斯坦福評論》的前員工們認為,該雜志吸引了一群持反對意見、思想自由的大學生,有人稱他們是被遺棄者,盡管他們主要是保守派或自由主義者,但多年來,他們在政治上存在分歧,并在內部就報紙上發表文章的前提進行辯論。幾十年來,《斯坦福評論》的版面顯示了另一個共同特點:他們認為自己的世界觀和西方價值體系在大學校園和全國范圍內都受到了攻擊。因此,這些學生從《斯坦福評論》的版面開始,并延續至其后的職業生涯中,一再向他們的意識形態對手揮拳相向。

《斯坦福評論》創刊初期

《斯坦福評論》是美國20世紀80年代涌現出的一系列保守派校園報紙之一。第一份同類報紙《達特茅斯評論》(Dartmouth Review)最終培養出了格雷戈里·福斯代爾、勞拉·英格拉哈姆、迪內希·德索薩和約瑟夫·拉戈等保守派評論家、作家和電視名人。在硅谷科技根深蒂固的校園里,《斯坦福評論》培養出如此多的科技投資者和工程師,也就不那么令人驚訝了。

《斯坦福評論》創刊時,蒂爾還是斯坦福大學哲學系的一名本科生。當時這所大學正在經歷一場意識形態的變革。在那次著名的游行活動中,美國總統候選人杰西·杰克遜牧師也加入了游行隊伍,學生們高呼:“嘿嘿,嗬嗬,西方文化必須消失。”一年后,斯坦福大學用《文化、思想與價值觀》(Culture, Ideas & Values)取代了《西方文明》(Western Civilization)課程,旨在納入更多由女性和有色人種撰寫的作品以及對歐洲之外的歷史研究。[蒂爾和大衛·薩克斯(PayPal早期高管和Craft Ventures創始人)后來在他們撰寫的《多樣性神話》(The Diversity Myth)一書中引用了一系列《斯坦福評論》文章和趣聞軼事。]

多年來,《斯坦福評論》發表的大部分內容都圍繞著校園新聞或外交政策(很少涉及商業或技術):例如關于美國前總統喬治·沃克·布什的政府與斯坦福大學的胡佛研究所(Hoover Institution)之間關系的報道;關于全校抵制葡萄的爭議;或者為何康多莉扎·賴斯被納入大學校長一職的考慮人選。

但《斯坦福評論》最初的一個重要使命是,在斯坦福大學這個自由主義濃厚的校園里,通過提出另類觀點,挑戰大多數人的想法,并引發“亟需的辯論”。學生們表達這些另類觀點的方法多種多樣,從深思熟慮的分析和報道,到挑釁式、甚至是直接攻擊式的觀點文章。撰寫《蒂爾傳》的馬克斯·查夫金寫道,在“2019年年末的漫長一天”里,他在斯坦福大學檔案館翻閱各期《斯坦福評論》。“翻閱這些報紙……讓人不斷地感到震驚,作者們竟然能夠在隨后的幾十年里積累如此巨大的力量,而沒有遭受任何明顯的打擊。”他在自己的書《逆反者》(The Contrarian)里寫道。

2004年的一篇文章標題是《同性戀將削弱婚姻》(Homosexuals Will Weaken Marriage)。1993年薩克斯撰寫的關于“光榮洞”的大膽專欄最后登上了《紐約時報》(New York Times)。在《斯坦福評論》歷史上臭名昭著的是瑞安·邦茲撰寫的一連串文章節選,其中一篇文章將多元文化主義(multiculturalism)的努力比作納粹焚書,這篇文章在他被美國前總統特朗普提名為美國第九巡回上訴法庭(Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals)的法官后不久浮出水面。白宮最終在一片反對聲中撤回了對他的提名。

在后來的幾十年里,一些作家紛紛道歉。薩克斯在《紐約時報》的報道中表示,他“為自己20多年前在大學里寫的一些東西感到難堪,我很抱歉寫了這些東西”,他用“恐怖”形容自己以前關于同性戀的觀點。邦茲說,他本應更加尊重他人,卻使用了“過激的言辭”。(薩克斯和邦茲沒有回復本文的評論請求。)

蒂爾告訴《財富》雜志,他擁護“最大限度的言論自由——尤其是帶有政治色彩的言論自由”。他為邦茲的文章辯護稱:“這完全在合理的言論范圍之內。”他還為《斯坦福評論》發表的一些更具爭議性的文章辯護,即使“有些具體的報道我個人是不會那么寫的”。

在談到更廣泛的問題時,蒂爾表示,《斯坦福評論》在2002年“明顯弱化了爭議性”,差不多就是文章開始登上互聯網的時代。他說,互聯網讓大學生們更難去探索觀點或發表有爭議的言論,而這些言論最終可能會改變他們的想法。

蒂爾說:“你必須明白,20世紀90年代的很多文章是在作者們認為會在大學校園里被閱讀一周的背景下[寫]出來的,而不是在未來幾十年都會出現在不朽的互聯網上。”

接受《財富》雜志采訪的其他編輯認為,一些較具反向思潮的文章是20歲年紀的人故意為引起爭論而寫的。一位不愿透露姓名的編輯說:“如果它沒有引起波瀾,如果人們不談論它,它就無關緊要。必須理解這一點。”

任何敢于翻閱《斯坦福評論》有關同性戀話題的存檔文章的人都很難忽略字里行間的諷刺意味,因為蒂爾和其他幾位前編輯或作者今天都是公開的同性戀者。報紙的一位前編輯杰夫·吉西亞提起此事時大笑起來,他說:“我是一名同性戀,事實證明,《斯坦福評論》大約三分之一的前編輯都是同性戀。”吉西亞在20世紀90年代末幫助蒂爾建立了對沖基金,后來又創辦了B2B媒體公司FierceMarkets。

PayPal向前走

2007年,《財富》雜志在一篇報道里用了“PayPal黑手黨”的說法,詳細描述了蒂爾、埃隆·馬斯克和里德·霍夫曼等眾多科技名人是如何在這家支付公司起步的。如果沒有《斯坦福評論》,PayPal的許多最早的員工可能一開始就不會加入PayPal。馬丁就是其中之一,還有杰克遜、拉布瓦、薩克斯、阿曼·韋爾吉、內森·林和鮑勃·麥格魯。

蒂爾說,1999年至2000年間,當他創辦PayPal的前身公司時,雇傭了許多《斯坦福評論》雜志的員工,他希望與那些他認為是朋友的人一起工作,而且這些人在某種程度上與他有共鳴——他們共同經歷了后來被稱為“網絡泡沫”時代的起起伏伏。

2002年擔任《斯坦福評論》編輯的亨利·托斯納說:“當然,并沒有人覺得(為蒂爾工作)是對任何人的某種公開邀請。”馬丁稱:“沒有任何正式的形式,甚至不一定是公開有意的聯系。它就這樣自然而然發生了。”

這里的工作不是對每個人敞開。正如幾位前編輯所承認的那樣,雖然《斯坦福評論》自發行以來的最初幾年里有很多女作者和女編輯,但最終進入蒂爾技術軌道的并不多——泰勒·朗斯代爾和Assembl的聯合創始人莉薩·華萊士都是《斯坦福評論》的編輯,后來都在Palantir工作,她們是為數不多的兩個例外。該報紙的校友網絡以男性為主,不過近年來這種情況已經開始慢慢改變,《斯坦福評論》最近的女性校友包括曾經在Palantir實習的安提戈涅·克塞諾普洛斯,以及曾經在8VC擔任助理、現任Founders Fund投資的公司Rippling招聘專員的安娜·米切爾。

對于那些最終進入科技領域的人來說,蒂爾的公司有時只是一個發射臺。薩克斯后來經營著市值數十億美元的風險投資公司Craft Ventures,該公司曾經為愛彼迎(Airbnb)、Lyft、Palantir和太空探索技術公司(SpaceX)提供支持。韋爾吉目前仍然擔任《斯坦福評論》下屬非營利組織的主席,并為學生提供指導,他后來成為早期風險投資和加速器500 Startups的首席運營官(他后來成立了風險投資二級基金)。鮑勃·麥格魯是微軟支持的人工智能巨頭OpenAI的研究副總裁。吉西亞創辦了一家專注于醫療保健的B2B媒體公司FierceMarkets。普雷馬爾·沙阿與他人共同創辦了小額貸款初創公司Kiva,杰克遜與他人共同創辦了一家名為TransitNet的加密貨幣所有權注冊公司。現在負責8VC的朗斯代爾曾經聯合創辦過Addepar和OpenGov等公司。

在《斯坦福評論》校友創辦的公司或組織中,有些公司或組織在某些方面頗具爭議。Palantir因為其與美國移民和海關執法局(U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)的關系而備受爭議。(一位前撰稿人說,與Palantir有關的爭議使它對《斯坦福評論》撰稿人更具吸引力。)朗斯代爾正計劃在奧斯汀建立一所新大學,教授所謂的《禁忌課程》。Rippling是一家由Founders Fund支持的公司,吸引了《斯坦福評論》的校友,其創始人帕克·康拉德曾經因為保險丑聞而從人力資源公司Zenefits辭職,最終不得不與美國證券交易委員會(SEC)達成和解。(大衛·薩克斯接替康拉德擔任Zenefits的臨時首席執行官。在達成和解時,康拉德表示很高興可以與美國證券交易委員會達成協議,并為自己在Zenefits建立的公司感到“無比自豪”。)

一位前撰稿人指出,有一條主線將這群《斯坦福評論》人清晰地聯系在一起:“他們蔑視自由主義的正統觀念和身份政治——比如政治正確。在他們眼里,這份報紙象征著一個由傳統來統治的社會,而不是自由思想家的天下。”

但大多數接受《財富》雜志采訪的前編輯都強調,《斯坦福評論》人脈網絡在思想上是多元化的,而不是思想統一。正如一些編輯所指出的,《斯坦福評論》的一些校友在支持哪位政治候選人、財政政策,以及美國是否應該支持俄烏沖突等問題上意見分歧很大。

“《斯坦福評論》的前員工們的政治觀點多樣性超出了人們的想象。我認為我們現在能夠清楚地看到這一點。”前編輯吉西亞說。

喬斯林·曼根是Him for Her組織的創始人,該組織是一家專門從事提高企業和初創公司董事會多樣性的社會影響組織。她認為,認知多樣性實際上只能來自跨越種族、性別、地域、年齡、教育背景和社會經濟水平的人際網絡,而大多數硅谷的主要網絡和早期公司及董事會都缺乏這種多樣性。曼根認為,像《斯坦福評論》這樣的圈子,在其中工作的人們可能是孤立于外界的,無法了解缺失的聲音或觀點。”曼根說:“我認為這歸結于存在于人性中的圈子行為——選擇每個人都認為可以帶來安全答案的人,也就是我認識的人。而這最終是最有風險的答案,因為這可能意味著你看不到其它的角度。”

《斯坦福評論》的持久影響

蒂爾說,《斯坦福評論》最終未能有效改變斯坦福校園。他認為是因為斯坦福校園過于循規蹈矩,幾乎沒有給異類思想留出空間。但他稱《斯坦福評論》“非常有影響力”,它讓人們的思維更加獨立。他表示,在某種情況下,即使它不能改變硅谷,也可以幫助人們在硅谷取得成功。

值得稱贊的是,正是蒂爾對一些不尋常想法的大膽追尋,讓他成為了億萬富翁——他相信支付將走向數字化,比特幣(Bitcoin)將變得有價值。他給一位哈佛大學(Harvard University)二年級學生一張50萬美元的支票,幫助他創建了一個名為“Thefacebook”的東西。(蒂爾還因為預測2008年房地產市場崩盤而聞名,盡管他從中套利的策略并不成功。)

正如杰克遜談到在PayPal工作經歷時所說的那樣:“這里從來沒有什么試金石,不是政治試題,也不是共和黨與民主黨之爭,而是圍繞著讓市場自行運轉,或技術最終如何在人類生活中發揮作用展開思考。”杰克遜說:“這是我們都在思考和相信的東西,它絕對與《斯坦福評論》一脈相承。”

盡管《斯坦福評論》的校友們已經積累了大量財富,建立了龐大的公司,形成了強大的圈子,但大學時代困擾年輕編輯們的一些難題似乎至今仍然揮之不去。正如蒂爾在1989年4月的編輯離任感言中寫道:“作為編輯,我學到了很多東西,但我仍然不知道如何說服人們傾聽。”(財富中文網)

譯者:珠珠

2000年1月的一天,斯坦福大學(Stanford University)一位名叫保羅·馬丁的年輕學生走進了位于美國帕洛阿爾托市的大學大道(University Avenue)的Confinity 初創科技公司。他是為了一份實習工作來找彼得·蒂爾的。

蒂爾當時還沒有成為著名的創始人和投資人,但他的面孔并不陌生,這要歸功于蒂爾為《斯坦福評論》(Stanford Review)的員工舉辦的一次次晚宴。《斯坦福評論》是斯坦福大學校內的一份保守派學生報紙,蒂爾在本科學習哲學專業時與他人共同創辦了這份報紙。在帕洛阿爾托的一家牛排館舉行的某次晚宴中,蒂爾給當時擔任報紙業務經理的馬丁留下了深刻印象。馬丁記得那次晚宴討論的話題涉獵很廣,從宗教到政治,從經濟到娛樂。

馬丁說:“他是一個令人印象深刻的人。如果他說:‘嘿,我有一家公司,我認為它很有可能取得巨大成功。’那么你就會[想]:‘也許我應該加入這家公司。’”

當馬丁到達Confinity公司時,他驚訝地發現《斯坦福評論》的另一位員工已經在Confinity工作了——那就是埃里克·杰克遜,他曾經在馬丁讀大一的時候擔任過報紙的主編。馬丁與蒂爾談話結束后,杰克遜帶著這位本科生去吃午飯,就在大學大道的街邊小店。馬丁回憶道:“他說:‘你知道嗎,這里正在起飛,我們一定會干出一番事情。如果你現在加入,你就會成為偉大事業的一部分。可你如果猶豫,機會就將消失。’”

不久,馬丁從斯坦福大學退學,也退出了學校田徑隊,開始在Confinity公司全職工作。這家公司最終更名為PayPal。

當時追隨彼得·蒂爾的有好幾十號人,馬丁和杰克遜只是其中之二。這里的工作已經悄然成為硅谷最令人羨慕的通往成功的途徑。這一切都始于《斯坦福評論》——1987 年,蒂爾與另一位未來的PayPal的早期員工諾曼·布克共同創辦的這份學生報紙。

蒂爾說:“我們在1987年創辦《斯坦福評論》時,顯然沒有料到幾十年后它會成為硅谷的一個令人難以置信的科技圈子。”他同意接受《財富》雜志的采訪,討論這份報紙。(與蒂爾一起通話的還有薩姆·沃爾夫,他是2018-19年度的前主編,通過《斯坦福評論》認識了蒂爾,目前在蒂爾的對沖基金擔任研究員。)

蒂爾在采訪中說:“我們在思想上當然并不完全一致,但我們有很多緊密的個人聯系,不僅是我和大家的聯系,還有他們互相之間的聯系——這就形成了一種團隊精神,對我們幫助很大……[PayPal]當然也經歷了很多波折和起伏——這種緊密的友情對我們共同度過公司的起起落落非常有幫助。”

在校園里,這份保守派的學生報紙在其30多年的歷史中曾經因為激怒左傾的斯坦福社區而聞名。每隔一段時間,《斯坦福評論》的某一篇慷慨激昂、引發爭議的評論文章就會登上全國頭條,這些文章或抨擊政治正確,或反對同性戀,或批評斯坦福大學的某位教授。包括一些《斯坦福評論》撰稿人在內的斯坦福學生在20世紀90年代對該校提起了訴訟,最終推動該校撤銷了禁止校園內激烈言論的規定。不過,除了少數幾個廣受關注的事件之外,該報在斯坦福校園之外基本上一直默默無名,即使其圈子已經擴大到相當規模的程度。

《斯坦福評論》的前編輯們說,早在蒂爾于1989年從斯坦福大學獲得本科學位后,他就一直在培養報紙的社區影響力。蒂爾至今仍然在參與這份報紙的工作。30多年來,他一直在家中或帕洛阿爾托的圣丹斯牛排館(Sundance steak house)等地為員工舉辦晚宴,討論世界大事和政治哲學問題,并向學生們了解大學生活和校園中的思潮。2017年,《斯坦福評論》為校友們舉辦了30周年聚會,現任主編沃克·斯圖爾特告訴《財富》雜志,就在去年,他還參加了蒂爾為報紙撰稿人舉辦的晚宴。

回顧一下《斯坦福評論》的歷史刊頭,就會發現這位傳奇投資人的圈子是多么龐大,多么緊密。PayPal的幾位聯合創始人或早期高管——蒂爾、Craft Ventures的大衛·薩克斯和美國駐瑞典前大使肯·霍威利——都曾經為該報撰稿。撰稿人還包括Palantir的三位創始人,該公司是一家國防技術公司,截至8月中旬市值接近330億美元。此外,還有Founders Fund的投資人基思·拉布瓦和Founders Fund的負責人約翰·呂蒂希,前者曾經在LinkedIn和Square任職。喬·朗斯代爾在擔任《斯坦福評論》主編后曾經為蒂爾工作,現在經營著風險投資公司8VC,他聘用了許多這家保守派報紙的員工,包括與他共同投資時間最長的合伙人之一亞歷克斯·穆爾,以及去年剛從斯坦福大學畢業的馬克斯韋爾·邁耶。(朗斯代爾與《斯坦福評論》的另一位編輯泰勒·考克斯組建了家庭,朗斯代爾的兄弟也曾經為該報撰稿。)

根據彭博億萬富豪指數(Bloomberg Billionaires Index),曾經在美國前總統唐納德·特朗普的過渡委員會任職的蒂爾本人的身價約為93億美元。這群校友在風險投資基金和科技公司方面的總資產是這一數字的好幾倍。Founders Fund上一次公布的資產管理規模為110億美元,朗斯代爾的8VC管理著超過60億美元的承諾資金,更不用說《斯坦福評論》的校友們已經在整個行業的科技公司中發揮了影響力。例如,《斯坦福評論》的前業務經理吉迪恩·于曾經在Facebook(現在的Meta)擔任過兩年的首席財務官,又比如《斯坦福評論》的校友鮑勃·麥格魯目前在OpenAI擔任研究副總裁。

六年前,前斯坦福大學學生安德魯·格拉納托花了將近一年的時間,仔細分析了《斯坦福評論》龐大的人脈網絡,并在學生雜志《斯坦福政治》(Stanford Politics)上發表的一篇文章,指出有近300名參與過《斯坦福評論》的校友曾經為蒂爾或朗斯代爾工作,或接受過他們的投資。自2018年以來,這些數字還在繼續上升。《財富》雜志發現,至少還有六人在Palantir、蒂爾資本、Founders Fund、蒂爾基金會(Thiel Capital)或朗斯代爾的風險投資基金8VC實習或工作,還有一些人在Founders Fund支持的Rippling等公司工作。

《財富》雜志采訪了包括蒂爾在內的10位現任或前任《斯坦福評論》編輯和工作人員,查閱了數百頁的非營利性文件,以及廣泛的公司網站、LinkedIn網頁和存檔的報紙文章,以了解這份學生報紙是如何成為硅谷科技生態系統中如此顯赫但又飽受爭議的平臺——還有將這群人聯系在一起的共同點。(其中兩人在匿名的情況下接受了《財富》雜志的采訪,一人要求保密,以便討論報紙上一些有爭議的文章。)

“現在回頭看,這份報紙是我職業生涯中非常重要的組成部分。”杰克遜說。他是《斯坦福評論》的編輯,也是PayPal的早期員工,后來與《斯坦福評論》的聯合創始人諾曼·布克一起成立了一家以保守派和基督教市場為重點的出版公司,并撰寫了一本關于PayPal的書。杰克遜說,他招募了《斯坦福評論》的校友,向他們尋求投資,并讓他們擔任自己多年來創辦的科技初創公司的顧問和董事。

《斯坦福評論》的前員工們認為,該雜志吸引了一群持反對意見、思想自由的大學生,有人稱他們是被遺棄者,盡管他們主要是保守派或自由主義者,但多年來,他們在政治上存在分歧,并在內部就報紙上發表文章的前提進行辯論。幾十年來,《斯坦福評論》的版面顯示了另一個共同特點:他們認為自己的世界觀和西方價值體系在大學校園和全國范圍內都受到了攻擊。因此,這些學生從《斯坦福評論》的版面開始,并延續至其后的職業生涯中,一再向他們的意識形態對手揮拳相向。

《斯坦福評論》創刊初期

《斯坦福評論》是美國20世紀80年代涌現出的一系列保守派校園報紙之一。第一份同類報紙《達特茅斯評論》(Dartmouth Review)最終培養出了格雷戈里·福斯代爾、勞拉·英格拉哈姆、迪內希·德索薩和約瑟夫·拉戈等保守派評論家、作家和電視名人。在硅谷科技根深蒂固的校園里,《斯坦福評論》培養出如此多的科技投資者和工程師,也就不那么令人驚訝了。

《斯坦福評論》創刊時,蒂爾還是斯坦福大學哲學系的一名本科生。當時這所大學正在經歷一場意識形態的變革。在那次著名的游行活動中,美國總統候選人杰西·杰克遜牧師也加入了游行隊伍,學生們高呼:“嘿嘿,嗬嗬,西方文化必須消失。”一年后,斯坦福大學用《文化、思想與價值觀》(Culture, Ideas & Values)取代了《西方文明》(Western Civilization)課程,旨在納入更多由女性和有色人種撰寫的作品以及對歐洲之外的歷史研究。[蒂爾和大衛·薩克斯(PayPal早期高管和Craft Ventures創始人)后來在他們撰寫的《多樣性神話》(The Diversity Myth)一書中引用了一系列《斯坦福評論》文章和趣聞軼事。]

多年來,《斯坦福評論》發表的大部分內容都圍繞著校園新聞或外交政策(很少涉及商業或技術):例如關于美國前總統喬治·沃克·布什的政府與斯坦福大學的胡佛研究所(Hoover Institution)之間關系的報道;關于全校抵制葡萄的爭議;或者為何康多莉扎·賴斯被納入大學校長一職的考慮人選。

但《斯坦福評論》最初的一個重要使命是,在斯坦福大學這個自由主義濃厚的校園里,通過提出另類觀點,挑戰大多數人的想法,并引發“亟需的辯論”。學生們表達這些另類觀點的方法多種多樣,從深思熟慮的分析和報道,到挑釁式、甚至是直接攻擊式的觀點文章。撰寫《蒂爾傳》的馬克斯·查夫金寫道,在“2019年年末的漫長一天”里,他在斯坦福大學檔案館翻閱各期《斯坦福評論》。“翻閱這些報紙……讓人不斷地感到震驚,作者們竟然能夠在隨后的幾十年里積累如此巨大的力量,而沒有遭受任何明顯的打擊。”他在自己的書《逆反者》(The Contrarian)里寫道。

2004年的一篇文章標題是《同性戀將削弱婚姻》(Homosexuals Will Weaken Marriage)。1993年薩克斯撰寫的關于“光榮洞”的大膽專欄最后登上了《紐約時報》(New York Times)。在《斯坦福評論》歷史上臭名昭著的是瑞安·邦茲撰寫的一連串文章節選,其中一篇文章將多元文化主義(multiculturalism)的努力比作納粹焚書,這篇文章在他被美國前總統特朗普提名為美國第九巡回上訴法庭(Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals)的法官后不久浮出水面。白宮最終在一片反對聲中撤回了對他的提名。

在后來的幾十年里,一些作家紛紛道歉。薩克斯在《紐約時報》的報道中表示,他“為自己20多年前在大學里寫的一些東西感到難堪,我很抱歉寫了這些東西”,他用“恐怖”形容自己以前關于同性戀的觀點。邦茲說,他本應更加尊重他人,卻使用了“過激的言辭”。(薩克斯和邦茲沒有回復本文的評論請求。)

蒂爾告訴《財富》雜志,他擁護“最大限度的言論自由——尤其是帶有政治色彩的言論自由”。他為邦茲的文章辯護稱:“這完全在合理的言論范圍之內。”他還為《斯坦福評論》發表的一些更具爭議性的文章辯護,即使“有些具體的報道我個人是不會那么寫的”。

在談到更廣泛的問題時,蒂爾表示,《斯坦福評論》在2002年“明顯弱化了爭議性”,差不多就是文章開始登上互聯網的時代。他說,互聯網讓大學生們更難去探索觀點或發表有爭議的言論,而這些言論最終可能會改變他們的想法。

蒂爾說:“你必須明白,20世紀90年代的很多文章是在作者們認為會在大學校園里被閱讀一周的背景下[寫]出來的,而不是在未來幾十年都會出現在不朽的互聯網上。”

接受《財富》雜志采訪的其他編輯認為,一些較具反向思潮的文章是20歲年紀的人故意為引起爭論而寫的。一位不愿透露姓名的編輯說:“如果它沒有引起波瀾,如果人們不談論它,它就無關緊要。必須理解這一點。”

任何敢于翻閱《斯坦福評論》有關同性戀話題的存檔文章的人都很難忽略字里行間的諷刺意味,因為蒂爾和其他幾位前編輯或作者今天都是公開的同性戀者。報紙的一位前編輯杰夫·吉西亞提起此事時大笑起來,他說:“我是一名同性戀,事實證明,《斯坦福評論》大約三分之一的前編輯都是同性戀。”吉西亞在20世紀90年代末幫助蒂爾建立了對沖基金,后來又創辦了B2B媒體公司FierceMarkets。

PayPal向前走

2007年,《財富》雜志在一篇報道里用了“PayPal黑手黨”的說法,詳細描述了蒂爾、埃隆·馬斯克和里德·霍夫曼等眾多科技名人是如何在這家支付公司起步的。如果沒有《斯坦福評論》,PayPal的許多最早的員工可能一開始就不會加入PayPal。馬丁就是其中之一,還有杰克遜、拉布瓦、薩克斯、阿曼·韋爾吉、內森·林和鮑勃·麥格魯。

蒂爾說,1999年至2000年間,當他創辦PayPal的前身公司時,雇傭了許多《斯坦福評論》雜志的員工,他希望與那些他認為是朋友的人一起工作,而且這些人在某種程度上與他有共鳴——他們共同經歷了后來被稱為“網絡泡沫”時代的起起伏伏。

2002年擔任《斯坦福評論》編輯的亨利·托斯納說:“當然,并沒有人覺得(為蒂爾工作)是對任何人的某種公開邀請。”馬丁稱:“沒有任何正式的形式,甚至不一定是公開有意的聯系。它就這樣自然而然發生了。”

這里的工作不是對每個人敞開。正如幾位前編輯所承認的那樣,雖然《斯坦福評論》自發行以來的最初幾年里有很多女作者和女編輯,但最終進入蒂爾技術軌道的并不多——泰勒·朗斯代爾和Assembl的聯合創始人莉薩·華萊士都是《斯坦福評論》的編輯,后來都在Palantir工作,她們是為數不多的兩個例外。該報紙的校友網絡以男性為主,不過近年來這種情況已經開始慢慢改變,《斯坦福評論》最近的女性校友包括曾經在Palantir實習的安提戈涅·克塞諾普洛斯,以及曾經在8VC擔任助理、現任Founders Fund投資的公司Rippling招聘專員的安娜·米切爾。

對于那些最終進入科技領域的人來說,蒂爾的公司有時只是一個發射臺。薩克斯后來經營著市值數十億美元的風險投資公司Craft Ventures,該公司曾經為愛彼迎(Airbnb)、Lyft、Palantir和太空探索技術公司(SpaceX)提供支持。韋爾吉目前仍然擔任《斯坦福評論》下屬非營利組織的主席,并為學生提供指導,他后來成為早期風險投資和加速器500 Startups的首席運營官(他后來成立了風險投資二級基金)。鮑勃·麥格魯是微軟支持的人工智能巨頭OpenAI的研究副總裁。吉西亞創辦了一家專注于醫療保健的B2B媒體公司FierceMarkets。普雷馬爾·沙阿與他人共同創辦了小額貸款初創公司Kiva,杰克遜與他人共同創辦了一家名為TransitNet的加密貨幣所有權注冊公司。現在負責8VC的朗斯代爾曾經聯合創辦過Addepar和OpenGov等公司。

在《斯坦福評論》校友創辦的公司或組織中,有些公司或組織在某些方面頗具爭議。Palantir因為其與美國移民和海關執法局(U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)的關系而備受爭議。(一位前撰稿人說,與Palantir有關的爭議使它對《斯坦福評論》撰稿人更具吸引力。)朗斯代爾正計劃在奧斯汀建立一所新大學,教授所謂的《禁忌課程》。Rippling是一家由Founders Fund支持的公司,吸引了《斯坦福評論》的校友,其創始人帕克·康拉德曾經因為保險丑聞而從人力資源公司Zenefits辭職,最終不得不與美國證券交易委員會(SEC)達成和解。(大衛·薩克斯接替康拉德擔任Zenefits的臨時首席執行官。在達成和解時,康拉德表示很高興可以與美國證券交易委員會達成協議,并為自己在Zenefits建立的公司感到“無比自豪”。)

一位前撰稿人指出,有一條主線將這群《斯坦福評論》人清晰地聯系在一起:“他們蔑視自由主義的正統觀念和身份政治——比如政治正確。在他們眼里,這份報紙象征著一個由傳統來統治的社會,而不是自由思想家的天下。”

但大多數接受《財富》雜志采訪的前編輯都強調,《斯坦福評論》人脈網絡在思想上是多元化的,而不是思想統一。正如一些編輯所指出的,《斯坦福評論》的一些校友在支持哪位政治候選人、財政政策,以及美國是否應該支持俄烏沖突等問題上意見分歧很大。

“《斯坦福評論》的前員工們的政治觀點多樣性超出了人們的想象。我認為我們現在能夠清楚地看到這一點。”前編輯吉西亞說。

喬斯林·曼根是Him for Her組織的創始人,該組織是一家專門從事提高企業和初創公司董事會多樣性的社會影響組織。她認為,認知多樣性實際上只能來自跨越種族、性別、地域、年齡、教育背景和社會經濟水平的人際網絡,而大多數硅谷的主要網絡和早期公司及董事會都缺乏這種多樣性。曼根認為,像《斯坦福評論》這樣的圈子,在其中工作的人們可能是孤立于外界的,無法了解缺失的聲音或觀點。”曼根說:“我認為這歸結于存在于人性中的圈子行為——選擇每個人都認為可以帶來安全答案的人,也就是我認識的人。而這最終是最有風險的答案,因為這可能意味著你看不到其它的角度。”

《斯坦福評論》的持久影響

蒂爾說,《斯坦福評論》最終未能有效改變斯坦福校園。他認為是因為斯坦福校園過于循規蹈矩,幾乎沒有給異類思想留出空間。但他稱《斯坦福評論》“非常有影響力”,它讓人們的思維更加獨立。他表示,在某種情況下,即使它不能改變硅谷,也可以幫助人們在硅谷取得成功。

值得稱贊的是,正是蒂爾對一些不尋常想法的大膽追尋,讓他成為了億萬富翁——他相信支付將走向數字化,比特幣(Bitcoin)將變得有價值。他給一位哈佛大學(Harvard University)二年級學生一張50萬美元的支票,幫助他創建了一個名為“Thefacebook”的東西。(蒂爾還因為預測2008年房地產市場崩盤而聞名,盡管他從中套利的策略并不成功。)

正如杰克遜談到在PayPal工作經歷時所說的那樣:“這里從來沒有什么試金石,不是政治試題,也不是共和黨與民主黨之爭,而是圍繞著讓市場自行運轉,或技術最終如何在人類生活中發揮作用展開思考。”杰克遜說:“這是我們都在思考和相信的東西,它絕對與《斯坦福評論》一脈相承。”

盡管《斯坦福評論》的校友們已經積累了大量財富,建立了龐大的公司,形成了強大的圈子,但大學時代困擾年輕編輯們的一些難題似乎至今仍然揮之不去。正如蒂爾在1989年4月的編輯離任感言中寫道:“作為編輯,我學到了很多東西,但我仍然不知道如何說服人們傾聽。”(財富中文網)

譯者:珠珠

In January 2000, a young Stanford University student named Paul Martin walked into the office of a fledgling tech company called Confinity on University Avenue in Palo Alto. He was there to see Peter Thiel about an internship.

Thiel, who had yet to become a renowned founder and investor, was already a familiar face, thanks to the dinners he had hosted for staff of the Stanford Review, a conservative student newspaper on Stanford’s campus that Thiel had cofounded as an undergraduate studying philosophy. Martin, a business manager for that paper, had been struck by one dinner in particular at a steak house in Palo Alto, where he recalls a wider discussion ranging from religion to politics, economics to entertainment.

“He’s just—he’s an impressive person,” Martin says. “And so if he says, ‘Hey, I’ve got this company, and I think that this has a real shot at being a huge success,’ then you’re going to [think], ‘I should probably get on board with that.’”

When Martin arrived at Confinity, he was surprised to see another Review staffer already working there: Eric Jackson, who had been editor-in-chief during Martin’s freshman year. Jackson took the undergrad out to lunch after his meeting with Thiel—to a little spot down the street on University Avenue. “He [said], ‘You know, this is taking off. This is going somewhere. And if you come now, then you’re going to be a part of something special. If you wait, this might be over,’” Martin recalls.

Martin dropped out of Stanford—and off the university’s track team—shortly after to start working full-time at Confinity. That company would eventually undergo a name change—to PayPal.

Martin and Jackson were just two of dozens of individuals who have followed Peter Thiel on what has quietly become one of the surest paths to an enviable job in Silicon Valley. It all starts at the Stanford Review, the student newspaper Thiel founded with Norman Book, another future early PayPal employee, in 1987.

“We obviously didn’t envision it becoming this incredible tech Silicon Valley network decades later when we started back in 1987,” says Thiel, who agreed to sit down for an interview with Fortune to discuss the paper. (Joining Thiel on the call was Sam Wolfe, a former editor-in-chief from 2018–19 who met Thiel via the Review and now works for him as a researcher at his hedge fund.)

“We certainly were not ideologically monolithic in any way,” Thiel said in the interview. “But the fact that there were a lot of strong personal connections that, not only I had with people, but they had with one another—gave it a certain esprit de corps that helped a lot…[PayPal] certainly had a lot of volatility, a lot of ups and downs—and that kind of intense camaraderie was what was super helpful to get through the boom and the bust.”

On campus, the conservative student newspaper has gained a reputation over its more than 30-year history for riling up the left-leaning Stanford community. And every once in a while, one of its impassioned and controversial opinion pieces criticizing political correctness, lambasting homosexuality, or calling out one of Stanford’s professors, has trickled into the national headlines. So did a lawsuit that was filed by Stanford students including some Review writers against the college in the ’90s, which ultimately compelled the university to overturn its speech code meant to put a stop to bigoted speech on campus. But beyond a handful of high-profile exceptions, the paper has largely remained unknown beyond Stanford’s elite campus, even if its network has grown large.

Former Review editors say that Thiel has been influential in cultivating the paper’s community, well after Thiel received his undergraduate degree from Stanford in 1989. And Thiel remains involved to this day, hosting dinners for staffers for more than three decades now—at his home, or at places like the Sundance steak house in Palo Alto—where he discusses world events and political philosophy and asks students questions about college life and what ideas are circulating around campus. In 2017, there was a 30th anniversary party for Review alumni, and the Stanford Review’s current editor-in-chief, Walker Stewart, told Fortune he had attended a dinner for Review writers hosted by Thiel in just the past year.

A look back through the archived mastheads of the Review shows how vast—but also how tight—the legendary investor’s orbit is. Several of PayPal’s cofounders or early executives—Thiel, Craft Ventures’ David Sacks, and former U.S. ambassador to Sweden Ken Howery—wrote for the paper, as did three founders of Palantir, a defense technology company with a market capitalization of nearly $33 billion as of mid-August. You can add Founders Fund investor Keith Rabois, who had stints at LinkedIn and Square, and Founders Fund principal John Luttig to the mix as well. Joe Lonsdale, who worked for Thiel after serving as editor-in-chief of the Review and now runs venture capital firm 8VC, has hired a number of the conservative paper’s staffers, including Alex Moore, one of Lonsdale’s longest-running investing partners, and, just last year, recent Stanford alum Maxwell Meyer. (Lonsdale married another Review editor, Tayler Cox, and Lonsdale’s brother wrote for the paper, too.)

Thiel himself, who served on former President Donald Trump’s transition committee, is estimated to be worth some $9.3 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Collectively—across venture capital funds and tech companies—this group of alumni has control over multiples of that. Founders Fund last reported $11 billion in assets under management. Lonsdale’s 8VC oversees more than $6 billion in committed capital. Not to mention Review alums who have gone on to wield influence at tech companies across the industry, such as Facebook (now Meta), where former Review business manager Gideon Yu was CFO for two years, or OpenAI, where Review alum Bob McGrew currently serves as vice president of research.

Six years ago, former Stanford student Andrew Granato spent almost a year poring through the Review’s vast network for an article in student magazine Stanford Politics—pinpointing nearly 300 Review alumni who had either worked for, or had received investments from, either Thiel or Lonsdale. And since 2018, those numbers have continued to rise. Fortune identified at least six more individuals who have gone on to intern or work at Palantir, Thiel Capital, Founders Fund, the Thiel Foundation, or Lonsdale’s venture capital fund, 8VC—as well as a handful of others who are working at companies like Rippling, which is backed by Founders Fund.

Fortune spoke with 10 current or former Review editors and staffers, including Thiel, and reviewed hundreds of pages of nonprofit filings as well as an extensive network of company websites, LinkedIn pages, and archived newspaper articles to understand how the student newspaper became such a prominent, yet controversial, launchpad into the Silicon Valley tech ecosystem—and to piece together the common thread that bound them together. (Two of the people spoke with Fortune on condition of anonymity, and one asked to remain confidential in order to discuss some of the newspaper’s controversial articles.)

“Now that I look back at it—it’s been a big part of what I did,” said Jackson, the Review editor and early PayPal employee who would go on to set up a conservative and Christian market-focused publishing company with Review cofounder Norman Book and author a book about PayPal. Jackson says he has recruited Review alumni, pitched them for investments, and brought them on as advisors and directors at tech startups he has founded over the years.

Former Review staffers say that the journal attracted a group of contrarian, free-thinking college kids some have described as outcasts who, despite being predominantly conservative or libertarian, disagreed on politics and internally debated the premise of stories published in the newspaper over the years. Decades of pages of the Review point to another shared characteristic: a belief that their worldview and the Western value system were under assault both on their university campus and across the nation. As a result, those students would repeatedly come out swinging at their ideological opponents, starting in the pages of the Review—and, in some cases, throughout their subsequent careers.

The early days of the Stanford Review

The Stanford Review was one of a series of conservative campus newspapers that popped up across the U.S. in the ’80s. The first of its kind, the Dartmouth Review, ended up fostering conservative commentators, writers, and television personalities like Gregory Fossedal, Laura Ingraham, Dinesh D’Souza, and Joseph Rago. It’s not so surprising that, on a campus ingrained in Silicon Valley tech, the Stanford Review has cultivated so many tech investors and engineers.

At the time the Review came into the picture, Thiel was a philosophy undergraduate at Stanford. And the university was undergoing an ideological transformation. There was the now-infamous march with presidential candidate the Rev. Jesse Jackson at which students chanted: “Hey hey, ho ho, Western culture’s got to go.” One year later, Stanford would replace its Western Civilization course with Culture, Ideas & Values, aimed at incorporating more works written by women and people of color as well as non-European historical studies. (Thiel and David Sacks, an early PayPal executive and a founder of Craft Ventures, would later cite a series of Review articles and anecdotes in the book they wrote on the topic: The Diversity Myth.)

Much of what has been published by the Review over the years revolved around campus news or foreign politics (with little on business or technology): stories on the connection between the George W. Bush administration and Stanford’s Hoover Institution; the controversy surrounding a campus-wide boycott on grapes; or why Condoleezza Rice should have been considered for the role of university president.

But a key part of the Stanford Review’s initial mission was to be combative with the majority on Stanford’s largely liberal-leaning campus by presenting alternative views—and to spark “much-needed debate,” according to the first editor’s note in 1987. The methods students used to deliver those alternative views varied from thoughtful analysis and reporting to provocative—or outright offensive—opinion pieces. Max Chafkin, who authored a biography of Thiel, wrote about a “long day at the end of 2019” spent in the Stanford archives, reading through issues of the Review. “To flip through the pages…is to be continually flabbergasted that the authors managed to amass so much power in the decades that followed without suffering any apparent blowback,” he wrote in his book, The Contrarian.

A 2004 story ran with the headline “Homosexuals Will Weaken Marriage.” A brazen column written by Sacks on “glory holes” in 1993 ended up featured in the New York Times. Infamous in Review history is a string of excerpts of articles written by Ryan Bounds, including one in which he likened multiculturalism efforts to a Nazi book burning, that surfaced shortly after he was nominated by President Trump for a seat on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The White House ended up withdrawing his nomination amid the backlash.

Some writers have apologized in the following decades. Sacks said at the time of the New York Times story that he was “embarrassed by some of the things I wrote in college over 20 years ago, and I am sorry I wrote them,” and that he was “horrified” by his old views on homosexuality. Bounds said he should have been more respectful and had used “overheated rhetoric.” (Sacks and Bounds didn’t return requests for comment for this article.)

Thiel told Fortune he believes in “maximalist free speech—especially of the sort that has a political valence,” defending Bounds’ articles as “well within the zone of reasonable discourse.” And he came to the defense of the Review publishing some of its more controversial pieces, even “if there were specific stories I would not personally have written.”

Speaking more broadly, Thiel says that the Review became “markedly less controversial” in 2002, around the same time that articles began to be published on the internet; he says that the internet has made it harder for undergraduates to explore ideas or say controversial things that they might end up changing their mind about.

“A lot of articles in the 1990s—what you have to contextualize is these were pieces [written] in a context where they thought it would be read for one week in a college setting—not where it would be on the imperishable internet for decades to come,” Thiel says.

Other editors who spoke with Fortune chalked up some of the more contrarian pieces to argumentative 20-year-olds who wanted to stir the pot. “If it doesn’t make waves, if people aren’t talking about it, it’s irrelevant,” says one editor, who would only speak on the topic anonymously. “That has to be understood.”

Anyone who dares to read back through the Review’s archived pieces on homosexuality would be hard-pressed to miss the irony between the lines, as Thiel—and several other former editors or writers—are now openly gay. One former editor laughed when he brought it up: “I’m gay—as are about one-third of the former Review editors, it turns out,” said Jeff Giesea, who helped Thiel set up his hedge fund in the late ’90s, then later founded B2B media company FierceMarkets.

To PayPal and beyond

In 2007 Fortune immortalized the descriptor “PayPal Mafia” in a story detailing how so many tech luminaries like Thiel, Elon Musk, and Reid Hoffman got their start at the payments company. But many of the company’s earliest employees likely wouldn’t have arrived at PayPal in the first place without the Review. Martin was one of them—as were Jackson, Rabois, Sacks, Aman Verjee, Nathan Linn, and Bob McGrew.

Thiel hired a number of Review staffers between 1999 and 2000 when he was starting the company that became PayPal, he says, noting that he wanted to work with people he considered friends and that he bonded with on some level—particularly during the ups and downs of the period now known as the “dotcom bubble.”

“There certainly wasn’t a sense that [working for Thiel] was an open invitation to anyone,” says Henry Towsner, who was editor of the Review in 2002. “There wasn’t anything formalized—or even necessarily overtly intentional” about the connections, Martin says. “It just kind of happened.”

Though not for everyone. As several former editors acknowledged, while there have been many female writers and editors for the Review since its first few years in circulation, not many of them ended up in Thiel’s tech orbit—Tayler Lonsdale and Assemble cofounder Lisa Wallace, both Review editors who went on to work at Palantir, being two of the few exceptions. The Review alumni network is predominantly male, though that has, slowly, started to change over the years, with more recent Review alumnae including Antigone Xenopoulos, who interned at Palantir, or Anna Mitchell, who was an associate at 8VC and is now a recruiter at Founders Fund portfolio company Rippling.

For those who did end up in the tech orbit, Thiel companies were sometimes just a launchpad. Sacks went on to run the multibillion-dollar venture capital firm Craft Ventures, which has backed Airbnb, Lyft, Palantir, and SpaceX. Verjee, who is still chairman of the Review’s affiliated nonprofit organization and mentors students, went on to become COO of early-stage VC and accelerator 500 Startups (he later set up a VC secondary fund). Bob McGrew is vice president of research at Microsoft-backed artificial intelligence juggernaut OpenAI. Giesea founded FierceMarkets, a B2B media business focused on health care. Premal Shah cofounded the microloan startup Kiva, and Jackson cofounded a crypto ownership registry called TransitNet. Lonsdale, who now runs 8VC, has cofounded companies like Addepar and OpenGov.

Some of the companies or organizations Review alumni have launched or ended up working for are controversial in some way. Palantir has been contentious owing to its ties to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (a former staff writer said the controversy around Palantir made it all the more alluring to Review writers). Lonsdale is planning to set up a new university in Austin that is teaching what it calls “forbidden courses.” Rippling, a Founders Fund–backed company that has attracted Review alums, is run by Parker Conrad, a founder who had resigned from human resources company Zenefits over an insurance scandal and ultimately had to settle with the SEC. (David Sacks succeeded Conrad as temporary CEO of Zenefits. At the time of the settlement, Conrad said he was pleased to have reached an agreement with the SEC and was “incredibly proud” of what he had built at Zenefits.)

One former writer notes there is a through line that clearly connects the Review bunch: A “disdain for liberal orthodoxy and identity politics—things like political correctness,” this staff writer says, adding, “They sort of see it as emblematic of a society governed by convention and not free thinkers.”

But most of the former editors who spoke with Fortune emphasized that the Review network is intellectually diverse and object to the notion that it is monolithic. As a handful of editors pointed out, some Review alumni vehemently disagree on which political candidates they support, fiscal policy, or whether they think the U.S. should support the war in Ukraine.

“There is more political diversity among Review alums than people might expect. I think we’re seeing that play out right now,” says former editor Giesea.

Jocelyn Mangan, founder of Him for Her, a social impact organization that specializes in boosting diversity on corporate and startup boards, argues that cognitive diversity can really only come from a network that spans race, gender, geography, age, educational background, and socioeconomic experiences—diversity most major Silicon Valley networks and early-stage companies and boards lack. Networks like those from the Review, where people go on to work with and for one another, can be insular and may not be privy to the voices or perspectives that are missing, according to Mangan. “I really think it comes down to human nature network behavior—of picking who everyone thinks is the safe answer, which is who I know,” Mangan says. “That ultimately is the riskiest answer, because it may mean that you don’t see around that corner.”

The lasting impact of the Review

In the end, Thiel says, the Stanford Review has not been very effective in changing Stanford’s campus, one he describes as too conformist, with little room for heterodox thought. But he contends the Review was “very formative” in making people more independent in their thinking—something, he notes, in some context, would help people succeed in Silicon Valley—if not change it.

To his credit, it’s Thiel’s bold swings on some rather unusual ideas that have made him a billionaire—his belief that payments would go digital, that Bitcoin would become valuable, or his $500,000 check to a Harvard sophomore building something called “Thefacebook.” (Thiel is also well known for predicting the 2008 housing market crash, though his strategy for monetizing it was not a success.)

As Jackson puts it, of working at PayPal: “There was never a litmus test, and they weren’t political ones per se—it wasn’t Republican versus Democrat,” he notes. Instead, it was the thinking around letting the market work itself out, or how technology could end up functioning in people’s lives: “That was the kind of stuff that we were all thinking and believing, and it definitely has the lineage that you can tie back to the Stanford Review,” Jackson says.

Though even as Review alums have amassed fortunes, built huge companies, and formed powerful networks, some quandaries that stumped the young editors back in college seem to still linger today. As Thiel wrote in April 1989 in his parting editor’s note: “I’ve learned a great deal as editor, but I still don’t know how one convinces people to listen.”