如今人們可能會看到,在快餐店端盤子的美國老年人以及在當地百貨店干兼職的老年人越來越少。

這些消失的員工不僅僅讓店面遲遲無法撤掉“需要人手”的招工啟事,同時也讓居高不下的通脹水平變得越發難以管控。

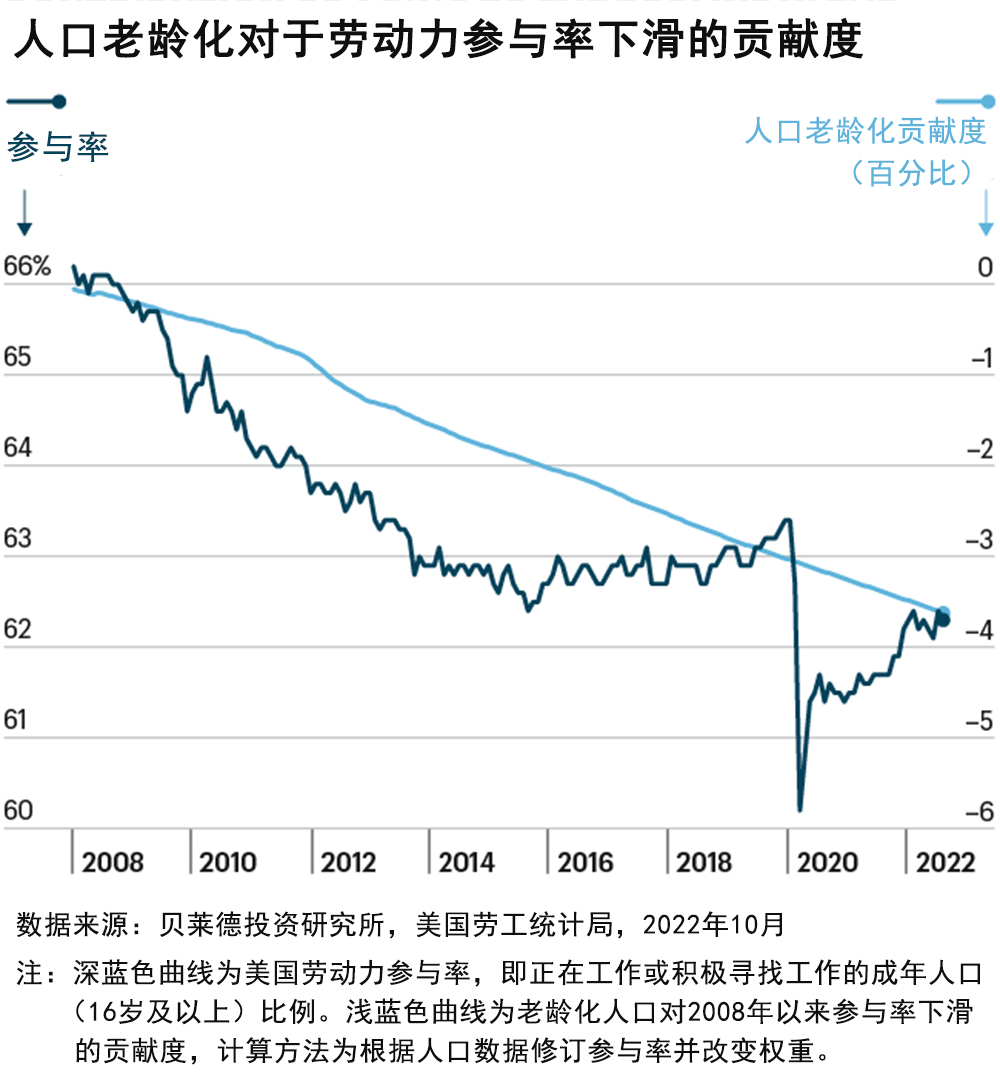

最近貝萊德(BlackRock)發布報告稱,美國65歲以上老年人的數量在不斷增長而且達到了退休年齡,此外,這些老年人不再回歸工作的比例已經達到了疫情前水平。這一現象會給勞動力短缺以及薪酬和雇員利用等問題帶來重大影響,同時還會波及當前和未來的通脹水平。

貝萊德分析師稱:“老齡化加劇了勞動力的短缺,推高了控制通脹的成本。”

畢馬威(KPMG)首席經濟師戴安娜?斯旺克對《財富》雜志說,從1995年到2020年2月,65歲以上人群勞動力參與率實際上在不斷增長。然而,當疫情爆發后,他們的參與率因一系列原因出現了下滑,包括該人群更容易受到病毒感染等,斯旺克說道。

盡管勞動力參與率較新冠疫情初期的暴跌有所恢復,但勞動力短缺的問題依然存在。其中很大一部分源于老年人不再回歸勞動力市場。貝萊德的報告顯示,截至2022年10月,常規退休已經讓130萬美國人(64歲以上)脫離了勞動力大軍,還有63萬人因提前退休而脫離。

11月30日,美聯儲主席杰羅姆?鮑威爾在布魯金斯學會發表講話時表示,當前的勞動力參與率缺口大多歸咎于“超量退休”,也就是退休人群數量超過了人們對老齡化人口退休的預期。在350萬的勞動力缺口中,超量退休貢獻的缺口超過了200萬人。

鮑威爾稱:“老年人的退休率仍在上升,而且他們在退休后回歸勞動力市場的比例也不夠大,無法有效減少過量退休人員的總數。”

斯旺克說,雖然這可能不是個大問題,但事實在于,當前沒有足夠多的年輕員工來完全替代即將退休并永久退出勞動力大軍的嬰兒潮人群。

“這些事件都碰到一塊了,人口老齡化,再加上疫情的催化,進一步破壞了我們增加適齡勞動力數量的能力,” 斯旺克說。“如果不實施重大改革,我們無法填補這些變化造成的勞動力空洞。”

就在上述缺口導致勞動力緊缺的同時,雇主為了吸引和留住所需的雇員一直在調高薪資,并直接放棄了其所期望的用工標準。貝萊德分析師還預測,僅靠美聯儲的加息也不大可能解決勞動力短缺這類窘境。

分析師寫道:“有鑒于人口的不斷老齡化,美國經濟將難以在不出現長期通脹的情況下實現增長。經濟活動將需要在更低水平運行,才能避免持續的薪資和價格通脹,尤其是勞動力密集的服務行業。”

盡管美聯儲在疫情初期稱,供應鏈問題和疫情相關因素(并非薪資)是價格高漲的推手,但鮑威爾在11月30日表示,這一現象隨著通脹的持續發生了改變。“不過這是一個時間的問題,通脹如今已經波及經濟的各個方面。盡管我依然認為,我們當前經歷的通脹與薪資沒有太大的關系,然而在未來,薪資增長很有可能成為通脹非常重要的推手。”

老齡化的嬰兒潮人群還存在額外成本,包括生活成本調整,例如社保將于明年實施的生活費調整。斯旺克指出,最終,6600多萬美國民眾將迎來8.7%的收入增幅。她說:“此舉為已然在負重前行的美聯儲增添了新的擔子。”她還表示,此舉可能會轉化為對需求的大幅提振,而美聯儲卻在努力壓低這一需求。

不幸的是,在應對人口結構問題帶來的勞動力參與率挑戰方面,沒有多少可在短期內發揮作用的簡單解決方案。最大的革命性解決方案就是移民改革,然而,聯邦層面對于通過修改美國移民政策來提供更多的勞動力沒有多少興趣。合法移民在2020年-2021年出現了斷崖式下跌,盡管目前有所回升,但依然是杯水車薪。

斯旺克說:“從我們面臨的緊張地緣政治局勢到氣候變化,再到極端天氣事件以及老齡化的人口結構和管控更加嚴格的移民政策,就算[美聯儲]成功消滅了這一次的通脹,但所有這一切都將讓這個世界成為通脹滋生的沃土。這也就意味著,我們不會回到21世紀10年代那個受到抑制、不慍不火、努力走出金融危機陰影的世界,而是通往一個大起大落、充滿通脹和加息的世界。”(財富中文網)

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

如今人們可能會看到,在快餐店端盤子的美國老年人以及在當地百貨店干兼職的老年人越來越少。

這些消失的員工不僅僅讓店面遲遲無法撤掉“需要人手”的招工啟事,同時也讓居高不下的通脹水平變得越發難以管控。

最近貝萊德(BlackRock)發布報告稱,美國65歲以上老年人的數量在不斷增長而且達到了退休年齡,此外,這些老年人不再回歸工作的比例已經達到了疫情前水平。這一現象會給勞動力短缺以及薪酬和雇員利用等問題帶來重大影響,同時還會波及當前和未來的通脹水平。

貝萊德分析師稱:“老齡化加劇了勞動力的短缺,推高了控制通脹的成本。”

畢馬威(KPMG)首席經濟師戴安娜?斯旺克對《財富》雜志說,從1995年到2020年2月,65歲以上人群勞動力參與率實際上在不斷增長。然而,當疫情爆發后,他們的參與率因一系列原因出現了下滑,包括該人群更容易受到病毒感染等,斯旺克說道。

盡管勞動力參與率較新冠疫情初期的暴跌有所恢復,但勞動力短缺的問題依然存在。其中很大一部分源于老年人不再回歸勞動力市場。貝萊德的報告顯示,截至2022年10月,常規退休已經讓130萬美國人(64歲以上)脫離了勞動力大軍,還有63萬人因提前退休而脫離。

11月30日,美聯儲主席杰羅姆?鮑威爾在布魯金斯學會發表講話時表示,當前的勞動力參與率缺口大多歸咎于“超量退休”,也就是退休人群數量超過了人們對老齡化人口退休的預期。在350萬的勞動力缺口中,超量退休貢獻的缺口超過了200萬人。

鮑威爾稱:“老年人的退休率仍在上升,而且他們在退休后回歸勞動力市場的比例也不夠大,無法有效減少過量退休人員的總數。”

斯旺克說,雖然這可能不是個大問題,但事實在于,當前沒有足夠多的年輕員工來完全替代即將退休并永久退出勞動力大軍的嬰兒潮人群。

“這些事件都碰到一塊了,人口老齡化,再加上疫情的催化,進一步破壞了我們增加適齡勞動力數量的能力,” 斯旺克說。“如果不實施重大改革,我們無法填補這些變化造成的勞動力空洞。”

就在上述缺口導致勞動力緊缺的同時,雇主為了吸引和留住所需的雇員一直在調高薪資,并直接放棄了其所期望的用工標準。貝萊德分析師還預測,僅靠美聯儲的加息也不大可能解決勞動力短缺這類窘境。

分析師寫道:“有鑒于人口的不斷老齡化,美國經濟將難以在不出現長期通脹的情況下實現增長。經濟活動將需要在更低水平運行,才能避免持續的薪資和價格通脹,尤其是勞動力密集的服務行業。”

盡管美聯儲在疫情初期稱,供應鏈問題和疫情相關因素(并非薪資)是價格高漲的推手,但鮑威爾在11月30日表示,這一現象隨著通脹的持續發生了改變。“不過這是一個時間的問題,通脹如今已經波及經濟的各個方面。盡管我依然認為,我們當前經歷的通脹與薪資沒有太大的關系,然而在未來,薪資增長很有可能成為通脹非常重要的推手。”

老齡化的嬰兒潮人群還存在額外成本,包括生活成本調整,例如社保將于明年實施的生活費調整。斯旺克指出,最終,6600多萬美國民眾將迎來8.7%的收入增幅。她說:“此舉為已然在負重前行的美聯儲增添了新的擔子。”她還表示,此舉可能會轉化為對需求的大幅提振,而美聯儲卻在努力壓低這一需求。

不幸的是,在應對人口結構問題帶來的勞動力參與率挑戰方面,沒有多少可在短期內發揮作用的簡單解決方案。最大的革命性解決方案就是移民改革,然而,聯邦層面對于通過修改美國移民政策來提供更多的勞動力沒有多少興趣。合法移民在2020年-2021年出現了斷崖式下跌,盡管目前有所回升,但依然是杯水車薪。

斯旺克說:“從我們面臨的緊張地緣政治局勢到氣候變化,再到極端天氣事件以及老齡化的人口結構和管控更加嚴格的移民政策,就算[美聯儲]成功消滅了這一次的通脹,但所有這一切都將讓這個世界成為通脹滋生的沃土。這也就意味著,我們不會回到21世紀10年代那個受到抑制、不慍不火、努力走出金融危機陰影的世界,而是通往一個大起大落、充滿通脹和加息的世界。”(財富中文網)

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

These days, you’re likely to see fewer older Americans handing over your fast food order or working part-time at the local grocery store.

Those missing workers are not just causing the “help wanted” signs to linger, but are actually making it harder to tame sky-high inflation levels.

The number of older Americans over the age of 65 is not only growing and hitting their retirement age, they’re also not coming back to the workforce in the numbers seen prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. That has major implications—not only for issues like worker shortages and compensation and employee leverage, but also for current and future inflation levels, according to a recent BlackRock report.

“Aging has worsened labor shortages, raising the cost of taming inflation,” BlackRock analysts report.

From 1995 to February 2020, the labor force participation rate among those over age 65 had actually been growing, Diane Swonk, chief economist for KPMG, tells Fortune. But when the pandemic hit, their participation rate dropped owing to a variety of reasons—including that this demographic was more vulnerable to the virus, Swonk says.

Although the labor force participation rate has recovered from the nosedive it took early in the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s still a lingering shortfall of workers. And a good portion of that stems from older workers not returning to the workforce. Routine retirements have taken 1.3 million Americans (age 64 and older) out of the workforce as of October 2022, BlackRock reports. Another 630,000 have left because of early retirement.

The current labor force participation rate gap is mostly the result of “excess retirements,” or exits above and beyond what would have been expected from aging alone, Fed Chair Jay Powell noted during an appearance on Wednesday. Those excess retirements are estimated to account for more than 2 million of the 3.5 million–person shortfall in the labor force.

“Older workers are still retiring at higher rates, and retirees do not appear to be returning to the labor force in sufficient numbers to meaningfully reduce the total number of excess retirees,” Powell said.

That perhaps wouldn’t be an issue, except for the fact that there aren’t enough younger workers to fully replace the sheer number of baby boomers who are retiring and permanently exiting the workforce, Swonk says.

“You really have this sort of collision of events of aging demographics that has been accelerated by the pandemic further undermining our ability to grow the prime-age labor force,” Swonk says. “Without major reforms, we’re just not going to be able to fill the hole that was left by those shifts.”

That shortfall makes for a tighter workforce where employers have been upping wages to attract and retain the employees they need, as well as simply forgoing the desired staffing levels. And the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes alone are unlikely to cure constraints like labor shortages, BlackRock’s analysts predict.

“An aging population will hurt the U.S. economy’s ability to grow without creating inflation longer term,” the analysts write. “Economic activity will need to run at a lower level to avoid persistent wage and price inflation, especially in the labor-heavy services sector.”

While the Fed reported early in the pandemic that supply-chain issues and pandemic-related conditions—not wages—were contributing to rising prices, that has shifted as inflation has persisted, Powell said Wednesday. “Over time though, inflation has now spread broadly through the economy. And while I would still say that the inflation we’re seeing now is not principally related to wages, we think that wage increases are probably going to be a very important part of the story going forward.”

There are additional costs tied to aging baby boomers, including cost of living adjustments like the one Social Security is set to implement next year. Essentially, over 66 million people are going to get an 8.7% raise, Swonk notes. “It ups the ante on the Fed at a time when they’re already challenged,” she says, adding that this likely translates to a pretty significant boost to demand when the Fed is trying to cool it.

Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of easy or short-term solutions that address the demographic challenges to the labor force participation rate. The biggest game-changing solution is immigration reform, but there’s been little appetite at the federal level to overhaul U.S. immigration policy to provide more workers. Legal immigration fell off a cliff in 2020 and 2021, and while it’s picking up again, it’s still not enough.

“From the geopolitical tensions we face to climate change to extreme weather events to the aging demographics and harsher borders—all of that makes for a more inflation-prone world even after [the Fed] slays this one inflation dragon. Which means we’re moving not back to the subdued, tepid, trying-to-recover-from-a-financial-crisis world that we were in during the 2010s, but to a much more boom-bust cycle punctuated by inflation and interest rate hikes,” Swonk says.