Moxy酒店是萬(wàn)豪國(guó)際(Marriott International)旗下一個(gè)主要針對(duì)年輕人的時(shí)尚酒店品牌。去年,萬(wàn)豪國(guó)際想在上海搞一個(gè)Moxy酒店的推廣活動(dòng),于是他們將這項(xiàng)任務(wù)委托給了專注中國(guó)市場(chǎng)的創(chuàng)意機(jī)構(gòu)趣民(Qumin)的負(fù)責(zé)人阿諾德·馬。

在美國(guó),萬(wàn)豪的Moxy酒店的前臺(tái)通常也會(huì)兼作酒吧,大堂的家具上也寫著很多專門針對(duì)年輕人的標(biāo)語(yǔ),比如“比薩是我的神寵”之類。萬(wàn)豪酒店深知,Moxy到了中國(guó)也必須進(jìn)行本土化改造,才能吸引中國(guó)的年輕人。因此他們聘請(qǐng)了華人出身的阿諾德·馬來(lái)推廣這個(gè)品牌。新一代中國(guó)的年輕消費(fèi)者有兩大特點(diǎn):一是開(kāi)始對(duì)舶來(lái)品持懷疑態(tài)度,二是由于經(jīng)濟(jì)和社會(huì)競(jìng)爭(zhēng)太激烈,越來(lái)越多的年輕人開(kāi)始了“躺平”的生活。

要完成這個(gè)項(xiàng)目,首先要研究年輕消費(fèi)者身上的矛盾。這也是趣民團(tuán)隊(duì)的首要任務(wù)。

首先,他們對(duì)中國(guó)的新一代年輕人進(jìn)行了一項(xiàng)非正式的民族性研究。研究發(fā)現(xiàn),新一代的中國(guó)年輕人對(duì)自己的能力擁有一種“與生俱來(lái)的自信”,并且渴望創(chuàng)造價(jià)值。因此在上海虹橋的第一家Moxy酒店開(kāi)業(yè)前,趣民請(qǐng)來(lái)了一群擁有狂熱粉絲的地下藝術(shù)家參與酒店內(nèi)飾部分的涂鴉,并且為開(kāi)業(yè)儀式準(zhǔn)備了手工雞尾酒。酒店的墻上繪滿了機(jī)器人和抽象畫等涂鴉,現(xiàn)場(chǎng)還有一名DJ播放音樂(lè)。此外,現(xiàn)場(chǎng)還準(zhǔn)備了一大堆粉色和紫色的塑料球和枕頭,枕頭還畫著吉他和紅嘴唇的圖案,它們都是專門為開(kāi)業(yè)儀式設(shè)計(jì)的。

與此同時(shí),他們還在抖音上同步發(fā)起了宣傳活動(dòng),不光邀請(qǐng)了一些網(wǎng)紅拍攝短視頻,同時(shí)也鼓勵(lì)粉絲制作了數(shù)千個(gè)探店短視頻。“我們形成了一種金字塔效應(yīng),讓大家制作與酒店相關(guān)的作品,然后把它變成營(yíng)銷內(nèi)容。”阿諾德·馬說(shuō)。

據(jù)萬(wàn)豪亞太地區(qū)(Marriott Asia Pacific)的品牌營(yíng)銷副總裁Jennie Toh介紹,“找到你身邊的Moxy”活動(dòng)已經(jīng)在中國(guó)的社交媒體渠道上收獲了“4.2億播放量和598萬(wàn)個(gè)贊”。Moxy酒店上海虹橋店于2021年6月開(kāi)業(yè)后,Moxy又在上海開(kāi)業(yè)了第二家店,并在中國(guó)大陸其他城市陸續(xù)開(kāi)業(yè)四家酒店。而更多分店也在“陸續(xù)籌備中”。

在這次宣傳活動(dòng)結(jié)束的幾周后,Moxy上海旗艦店的入住率增長(zhǎng)了500%。雖然萬(wàn)豪沒(méi)有透露今年受嚴(yán)格的疫情防控影響,這種成功勢(shì)頭是否保持了下去,不過(guò)萬(wàn)豪的高管們表示,他們的在華業(yè)務(wù)仍然十分強(qiáng)勁。萬(wàn)豪的首席執(zhí)行官安東尼·卡普阿諾在8月初的財(cái)報(bào)會(huì)議上說(shuō):“(萬(wàn)豪及其伙伴的)很多酒店都受益于中國(guó)國(guó)內(nèi)旅行客流量的增加,盡管個(gè)別城市由于疫情防控而一度按下暫停健。”

萬(wàn)豪對(duì)這次營(yíng)銷活動(dòng)的成果十分滿意,雖然萬(wàn)豪的高管們也不完全理解阿諾德·馬是如何達(dá)到這個(gè)結(jié)果的。阿諾德·馬表示:“(一位萬(wàn)豪高管)曾經(jīng)對(duì)我說(shuō):‘兄弟,我真的不理解這些短視頻到底是怎么回事。’”

當(dāng)然,外國(guó)高管肯定無(wú)法輕易理解中國(guó)的年輕人是怎么想的。根據(jù)來(lái)自中國(guó)數(shù)字營(yíng)銷機(jī)構(gòu)Alarice的數(shù)據(jù),中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群(也就是1997年至2012年間出生的人群)已占全國(guó)總?cè)丝诘?9%,到2025年,這個(gè)比例將達(dá)到27%。華興資本(China Renaissance)的數(shù)據(jù)也表明,從現(xiàn)在起到2035年,中國(guó)“Z世代”人群的消費(fèi)力將增長(zhǎng)四倍,達(dá)到2.4萬(wàn)億美元。但中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群也有一些新的個(gè)性特點(diǎn)——例如偏愛(ài)國(guó)貨、討厭過(guò)度工作等等,這些與前幾代年輕人有明顯區(qū)別。面對(duì)中國(guó)這個(gè)14億人口的龐大市場(chǎng),西方品牌要想保持影響力,就必須重新思考它們的對(duì)華戰(zhàn)略,學(xué)習(xí)一套新的規(guī)則,來(lái)破解新一代中國(guó)年輕人的消費(fèi)密碼。

脫節(jié)

新一代的中國(guó)年輕人,不僅是外國(guó)高管無(wú)法理解的存在,甚至就連老一輩的中國(guó)人,也很難真正理解這些在相對(duì)富足的年代和“微信時(shí)代”里成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的年輕人。

中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群,指的是出生于1997年至2012年間的年輕人。就在短短十幾年里,中國(guó)從一潭死水般的狀態(tài)迅速崛起成了一個(gè)全球強(qiáng)國(guó),其經(jīng)濟(jì)總量增長(zhǎng)了8倍,從世界第七變成了世界第二大經(jīng)濟(jì)體。1997年也就是第一批“Z世代”人群出生時(shí),中國(guó)的經(jīng)濟(jì)繁榮才剛剛拉開(kāi)序幕,當(dāng)時(shí)的人均GDP只有781美元。到2007年,也就是這批孩子長(zhǎng)到10歲時(shí),中國(guó)的人均GDP已經(jīng)增長(zhǎng)了兩倍多,達(dá)到2,694美元。所以這些年輕人生來(lái)就認(rèn)為中國(guó)是一個(gè)經(jīng)濟(jì)超級(jí)大國(guó),這種認(rèn)識(shí)與他們吃過(guò)苦的父輩是有天壤之別的。

“這種兩代人之間的差距之大,可以說(shuō)歷史中見(jiàn)所未見(jiàn)。”阿諾德·馬說(shuō)。

博圣軒(Daxue Consulting)的營(yíng)銷總監(jiān)阿利森·馬爾姆斯滕表示,智能手機(jī)更加劇了這種代際脫節(jié)。新一代年輕人是由他們的數(shù)字生活定義的。“在西方,人們正在嘗試將社交媒體與電商結(jié)合起來(lái),但是在中國(guó),他們這樣做已經(jīng)好幾年了。這意味著你的社交時(shí)間和網(wǎng)購(gòu)時(shí)間是深度融合的,你的消費(fèi)與愛(ài)好也是深度融合的。”

新老一代的認(rèn)知脫節(jié),也讓年輕人中出現(xiàn)了“躺平”和“內(nèi)卷”之類的新詞。糾其原因,是上一代人愿意通過(guò)付出更長(zhǎng)的工作時(shí)間來(lái)促進(jìn)國(guó)家的GDP增長(zhǎng)。但這一代的年輕人卻很難輕易看到回報(bào)——因?yàn)橹袊?guó)已經(jīng)是全球頂尖的經(jīng)濟(jì)體了,而他們辛苦工作的回報(bào)卻是遞減的。

咨詢公司青年中國(guó)集團(tuán)(Young China Group)的首席執(zhí)行官扎克·迪赫特瓦爾德表示,新一代的中國(guó)年輕人是在一個(gè)“超高壓的環(huán)境”里成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的。他們從小被逼著上好中學(xué)、好高中,找一個(gè)好工作、好配偶。但事實(shí)是競(jìng)爭(zhēng)雖然越來(lái)越激烈,但回報(bào)越卻來(lái)越少。今年6月,中國(guó)的青年失業(yè)率達(dá)到有史以來(lái)最高的19.3%。買房對(duì)年輕人來(lái)說(shuō)是一個(gè)越來(lái)越遙不可及的夢(mèng)想。2020年,中國(guó)的城市平均房?jī)r(jià)達(dá)到人均年收入的13.7倍,也就是說(shuō)買房的困難程度是美國(guó)的兩倍。“年輕人有了一種無(wú)助感,無(wú)論他們?nèi)绾闻ぷ鳎麄兿胍臇|西都是遙不可及的。”迪赫特瓦爾德說(shuō)。

有專家表示,“躺平”和“內(nèi)卷”不光只是網(wǎng)絡(luò)熱詞,而是正在整個(gè)中國(guó)社會(huì)蔓延。一些白領(lǐng)選擇辭掉高壓工作搬到農(nóng)村生活。還有專家認(rèn)為,中國(guó)生育率的下跌,至少有一部分原因,是因?yàn)橹袊?guó)年輕女性不愿意屈從于社會(huì)的壓力而生孩子。

Alarice公司的創(chuàng)始人阿什利·杜達(dá)內(nèi)洛克表示,要想通過(guò)宣傳“偷懶文化”吸引這些身心被掏空的年輕人,并不是一件容易的事情。不過(guò)很多在華的外國(guó)品牌都想吸引這部分年輕人,但結(jié)果卻是參差不齊。

去年,有一位叫利路修(Vladislav Ivanov)的俄羅斯男孩中國(guó)的一個(gè)音樂(lè)綜藝節(jié)目里火了,成了“躺平”運(yùn)動(dòng)的一個(gè)代言人。利路修在參加了節(jié)目后,千方百計(jì)想早點(diǎn)輸?shù)舯荣悾層^眾別投票給他,好打包行李回家休息。結(jié)果網(wǎng)友們愛(ài)上了他的“躺平”精神,偏偏投票不讓他下課,結(jié)果他足足在這個(gè)節(jié)目里待了十集,幾乎被網(wǎng)友逼著參加完了一整季的節(jié)目。

此后,普拉達(dá)(Prada)、古馳(Gucci)和芬迪(Fendi)等外國(guó)時(shí)尚品牌都找利路修來(lái)代言在中國(guó)的廣告。比如在美國(guó)綠箭公司(Wrigley)的一個(gè)廣告里,利路修無(wú)論是上班下班還是健身的時(shí)候都嚼著口香糖。這說(shuō)明這些品牌都想借“躺平”文化分一杯羹。

國(guó)潮

阿諾德·馬認(rèn)為,如果說(shuō)這一代中國(guó)年輕人是“躺平的一代”,這種說(shuō)法顯然不正確。通過(guò)萬(wàn)豪集團(tuán)的這次營(yíng)銷活動(dòng),他發(fā)現(xiàn)中國(guó)的年輕人未必都是躺平的,他們也想找到自己的激情,并以某一種方式去追求它。

他還表示,在萬(wàn)豪集團(tuán)的這次任務(wù)中,最難的部分,就是如何向年輕人推銷一個(gè)外國(guó)品牌。“以前,西方品牌在中國(guó)自帶一種高級(jí)感,但現(xiàn)在不是這樣了。”

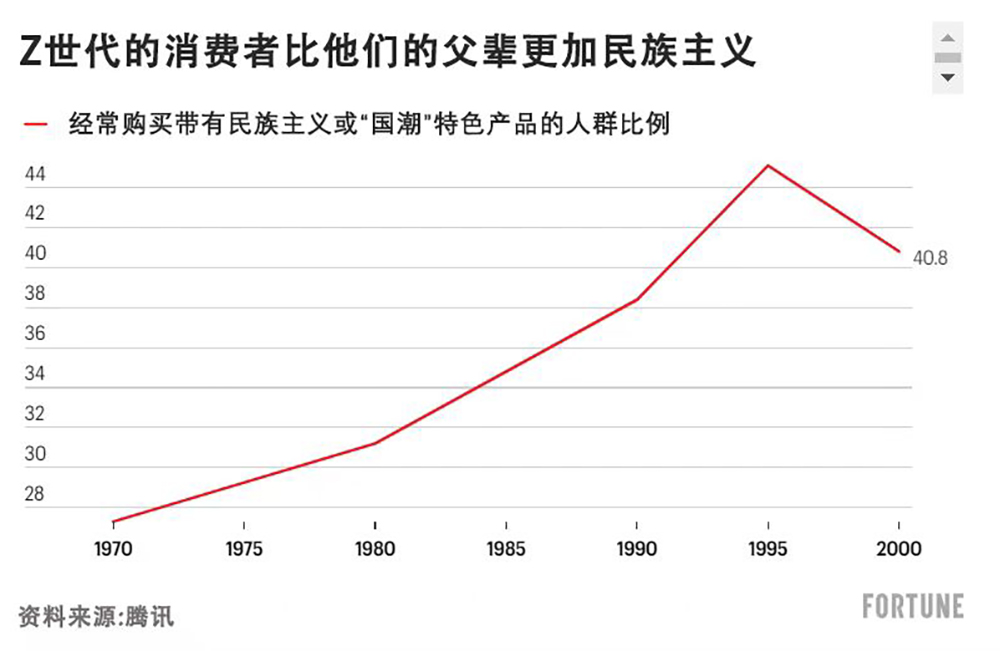

隨著近年來(lái)中美摩擦不斷擴(kuò)大,以購(gòu)買國(guó)貨為榮的“國(guó)潮”正在興起,特別是在“Z世代”的年輕人中。麥肯錫公司(McKinsey)在2020年曾經(jīng)對(duì)15個(gè)城市的5,000人作過(guò)一項(xiàng)調(diào)查,結(jié)果顯示,2011年以來(lái),更愿意購(gòu)買國(guó)產(chǎn)而不是外國(guó)品牌的比例已經(jīng)由15%上升到了85%,而“國(guó)潮”的消費(fèi)主力就是“Z世代”。騰訊最近的一項(xiàng)調(diào)查也顯示,45%的“95后”年輕人經(jīng)常購(gòu)買有“國(guó)潮”元素的產(chǎn)品,而在90后和80后消費(fèi)者中,這一比例分別為38%和27%。

2021年3月,一些中國(guó)的年輕人以燒掉耐克鞋的方式,抗議耐克公司(Nike)在新疆棉問(wèn)題上的立場(chǎng)。就在今年8月,大量社交媒體用戶還威脅抵制士力架(Snickers),因?yàn)樵摴驹谝粍t外國(guó)廣告里稱中國(guó)臺(tái)灣地區(qū)是一個(gè)國(guó)家。就在“士力架事件”發(fā)生前不久,美國(guó)國(guó)會(huì)眾議院議長(zhǎng)南希·佩洛西竄訪了臺(tái)灣,造成了兩岸關(guān)系緊張局面急劇升高。士力架的美國(guó)母公司瑪氏箭牌(Mars Wrigley)在8月5日發(fā)表了一則道歉聲明,稱臺(tái)灣地區(qū)“是中國(guó)領(lǐng)土不可分割的一部分”。

博圣軒的營(yíng)銷總監(jiān)阿利森·馬爾姆斯滕說(shuō):“中國(guó)的‘Z世代’已經(jīng)以自己的方式‘覺(jué)醒’了。中國(guó)年輕人對(duì)外國(guó)影響力是持非常批判的態(tài)度的。”

因此,在中國(guó)的外國(guó)品牌絕不能忽視“國(guó)潮”的威力,從而輸給愛(ài)國(guó)的競(jìng)爭(zhēng)對(duì)手。因此,很多外國(guó)公司也正在與本地品牌和機(jī)構(gòu)開(kāi)展合作。

阿諾德·馬表示:“國(guó)潮有正宗性和民族性兩個(gè)特點(diǎn)。外國(guó)品牌要想做好這件事情,唯一的辦法就是與本土伙伴合作。”例如奧利奧(Oreo)與故宮博物院的合作就是一次成功的合作。

2019年,奧利奧和故宮博物院聯(lián)合推出了以皇室為主題的奧利奧餅干,包括綠茶、紅豆和荔枝玫瑰等口味——這些都是康熙皇帝喜歡的點(diǎn)心。奧利奧表示,這些新品牌上線首日就賣掉了76萬(wàn)盒,并且為它的天貓旗艦店帶來(lái)了26萬(wàn)新粉絲。

也有一些洋品牌,畫虎不成反類犬,消費(fèi)者一眼就看出這是假冒的“國(guó)潮”。

比如美國(guó)巧克力制造商德芙(Dove)也在2020年農(nóng)歷新年推出了故宮主題的巧克力。但網(wǎng)友們紛紛吐槽稱,這些巧克力幾乎沒(méi)有任何中國(guó)歷史元素,只不過(guò)是偽“國(guó)潮”。

Alarice公司的創(chuàng)始人阿什利·杜達(dá)內(nèi)洛克稱:“有些合作是非常膚淺的,或者對(duì)文化引用不當(dāng),這反而會(huì)危及品牌的聲譽(yù)。”

最后,迪赫特瓦爾德指出,外國(guó)品牌必須以謙卑的態(tài)度對(duì)待中國(guó)市場(chǎng)。

他表示:“你必須專門針對(duì)中國(guó)年輕人市場(chǎng)設(shè)計(jì)產(chǎn)品,這意味著你要真正了解他們想要什么。很多國(guó)際品牌都在投資收集這些市場(chǎng)情報(bào),但有時(shí)它們并未委托中國(guó)團(tuán)隊(duì)來(lái)制定這些戰(zhàn)略。”

阿諾德·馬認(rèn)為,西方品牌光靠認(rèn)知度就能夠占領(lǐng)市場(chǎng)的日子已經(jīng)一去不復(fù)返了。

他說(shuō):“你不能以為自己是一個(gè)歷史悠久的外國(guó)品牌,就以為自己可以予取予求,現(xiàn)在這樣只會(huì)讓人覺(jué)得你很傲慢。人們不在乎你是從哪兒來(lái)的,只在乎你現(xiàn)在在做什么。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:樸成奎

Moxy酒店是萬(wàn)豪國(guó)際(Marriott International)旗下一個(gè)主要針對(duì)年輕人的時(shí)尚酒店品牌。去年,萬(wàn)豪國(guó)際想在上海搞一個(gè)Moxy酒店的推廣活動(dòng),于是他們將這項(xiàng)任務(wù)委托給了專注中國(guó)市場(chǎng)的創(chuàng)意機(jī)構(gòu)趣民(Qumin)的負(fù)責(zé)人阿諾德·馬。

在美國(guó),萬(wàn)豪的Moxy酒店的前臺(tái)通常也會(huì)兼作酒吧,大堂的家具上也寫著很多專門針對(duì)年輕人的標(biāo)語(yǔ),比如“比薩是我的神寵”之類。萬(wàn)豪酒店深知,Moxy到了中國(guó)也必須進(jìn)行本土化改造,才能吸引中國(guó)的年輕人。因此他們聘請(qǐng)了華人出身的阿諾德·馬來(lái)推廣這個(gè)品牌。新一代中國(guó)的年輕消費(fèi)者有兩大特點(diǎn):一是開(kāi)始對(duì)舶來(lái)品持懷疑態(tài)度,二是由于經(jīng)濟(jì)和社會(huì)競(jìng)爭(zhēng)太激烈,越來(lái)越多的年輕人開(kāi)始了“躺平”的生活。

要完成這個(gè)項(xiàng)目,首先要研究年輕消費(fèi)者身上的矛盾。這也是趣民團(tuán)隊(duì)的首要任務(wù)。

首先,他們對(duì)中國(guó)的新一代年輕人進(jìn)行了一項(xiàng)非正式的民族性研究。研究發(fā)現(xiàn),新一代的中國(guó)年輕人對(duì)自己的能力擁有一種“與生俱來(lái)的自信”,并且渴望創(chuàng)造價(jià)值。因此在上海虹橋的第一家Moxy酒店開(kāi)業(yè)前,趣民請(qǐng)來(lái)了一群擁有狂熱粉絲的地下藝術(shù)家參與酒店內(nèi)飾部分的涂鴉,并且為開(kāi)業(yè)儀式準(zhǔn)備了手工雞尾酒。酒店的墻上繪滿了機(jī)器人和抽象畫等涂鴉,現(xiàn)場(chǎng)還有一名DJ播放音樂(lè)。此外,現(xiàn)場(chǎng)還準(zhǔn)備了一大堆粉色和紫色的塑料球和枕頭,枕頭還畫著吉他和紅嘴唇的圖案,它們都是專門為開(kāi)業(yè)儀式設(shè)計(jì)的。

與此同時(shí),他們還在抖音上同步發(fā)起了宣傳活動(dòng),不光邀請(qǐng)了一些網(wǎng)紅拍攝短視頻,同時(shí)也鼓勵(lì)粉絲制作了數(shù)千個(gè)探店短視頻。“我們形成了一種金字塔效應(yīng),讓大家制作與酒店相關(guān)的作品,然后把它變成營(yíng)銷內(nèi)容。”阿諾德·馬說(shuō)。

據(jù)萬(wàn)豪亞太地區(qū)(Marriott Asia Pacific)的品牌營(yíng)銷副總裁Jennie Toh介紹,“找到你身邊的Moxy”活動(dòng)已經(jīng)在中國(guó)的社交媒體渠道上收獲了“4.2億播放量和598萬(wàn)個(gè)贊”。Moxy酒店上海虹橋店于2021年6月開(kāi)業(yè)后,Moxy又在上海開(kāi)業(yè)了第二家店,并在中國(guó)大陸其他城市陸續(xù)開(kāi)業(yè)四家酒店。而更多分店也在“陸續(xù)籌備中”。

在這次宣傳活動(dòng)結(jié)束的幾周后,Moxy上海旗艦店的入住率增長(zhǎng)了500%。雖然萬(wàn)豪沒(méi)有透露今年受嚴(yán)格的疫情防控影響,這種成功勢(shì)頭是否保持了下去,不過(guò)萬(wàn)豪的高管們表示,他們的在華業(yè)務(wù)仍然十分強(qiáng)勁。萬(wàn)豪的首席執(zhí)行官安東尼·卡普阿諾在8月初的財(cái)報(bào)會(huì)議上說(shuō):“(萬(wàn)豪及其伙伴的)很多酒店都受益于中國(guó)國(guó)內(nèi)旅行客流量的增加,盡管個(gè)別城市由于疫情防控而一度按下暫停健。”

萬(wàn)豪對(duì)這次營(yíng)銷活動(dòng)的成果十分滿意,雖然萬(wàn)豪的高管們也不完全理解阿諾德·馬是如何達(dá)到這個(gè)結(jié)果的。阿諾德·馬表示:“(一位萬(wàn)豪高管)曾經(jīng)對(duì)我說(shuō):‘兄弟,我真的不理解這些短視頻到底是怎么回事。’”

當(dāng)然,外國(guó)高管肯定無(wú)法輕易理解中國(guó)的年輕人是怎么想的。根據(jù)來(lái)自中國(guó)數(shù)字營(yíng)銷機(jī)構(gòu)Alarice的數(shù)據(jù),中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群(也就是1997年至2012年間出生的人群)已占全國(guó)總?cè)丝诘?9%,到2025年,這個(gè)比例將達(dá)到27%。華興資本(China Renaissance)的數(shù)據(jù)也表明,從現(xiàn)在起到2035年,中國(guó)“Z世代”人群的消費(fèi)力將增長(zhǎng)四倍,達(dá)到2.4萬(wàn)億美元。但中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群也有一些新的個(gè)性特點(diǎn)——例如偏愛(ài)國(guó)貨、討厭過(guò)度工作等等,這些與前幾代年輕人有明顯區(qū)別。面對(duì)中國(guó)這個(gè)14億人口的龐大市場(chǎng),西方品牌要想保持影響力,就必須重新思考它們的對(duì)華戰(zhàn)略,學(xué)習(xí)一套新的規(guī)則,來(lái)破解新一代中國(guó)年輕人的消費(fèi)密碼。

脫節(jié)

新一代的中國(guó)年輕人,不僅是外國(guó)高管無(wú)法理解的存在,甚至就連老一輩的中國(guó)人,也很難真正理解這些在相對(duì)富足的年代和“微信時(shí)代”里成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的年輕人。

中國(guó)的“Z世代”人群,指的是出生于1997年至2012年間的年輕人。就在短短十幾年里,中國(guó)從一潭死水般的狀態(tài)迅速崛起成了一個(gè)全球強(qiáng)國(guó),其經(jīng)濟(jì)總量增長(zhǎng)了8倍,從世界第七變成了世界第二大經(jīng)濟(jì)體。1997年也就是第一批“Z世代”人群出生時(shí),中國(guó)的經(jīng)濟(jì)繁榮才剛剛拉開(kāi)序幕,當(dāng)時(shí)的人均GDP只有781美元。到2007年,也就是這批孩子長(zhǎng)到10歲時(shí),中國(guó)的人均GDP已經(jīng)增長(zhǎng)了兩倍多,達(dá)到2,694美元。所以這些年輕人生來(lái)就認(rèn)為中國(guó)是一個(gè)經(jīng)濟(jì)超級(jí)大國(guó),這種認(rèn)識(shí)與他們吃過(guò)苦的父輩是有天壤之別的。

“這種兩代人之間的差距之大,可以說(shuō)歷史中見(jiàn)所未見(jiàn)。”阿諾德·馬說(shuō)。

博圣軒(Daxue Consulting)的營(yíng)銷總監(jiān)阿利森·馬爾姆斯滕表示,智能手機(jī)更加劇了這種代際脫節(jié)。新一代年輕人是由他們的數(shù)字生活定義的。“在西方,人們正在嘗試將社交媒體與電商結(jié)合起來(lái),但是在中國(guó),他們這樣做已經(jīng)好幾年了。這意味著你的社交時(shí)間和網(wǎng)購(gòu)時(shí)間是深度融合的,你的消費(fèi)與愛(ài)好也是深度融合的。”

新老一代的認(rèn)知脫節(jié),也讓年輕人中出現(xiàn)了“躺平”和“內(nèi)卷”之類的新詞。糾其原因,是上一代人愿意通過(guò)付出更長(zhǎng)的工作時(shí)間來(lái)促進(jìn)國(guó)家的GDP增長(zhǎng)。但這一代的年輕人卻很難輕易看到回報(bào)——因?yàn)橹袊?guó)已經(jīng)是全球頂尖的經(jīng)濟(jì)體了,而他們辛苦工作的回報(bào)卻是遞減的。

咨詢公司青年中國(guó)集團(tuán)(Young China Group)的首席執(zhí)行官扎克·迪赫特瓦爾德表示,新一代的中國(guó)年輕人是在一個(gè)“超高壓的環(huán)境”里成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的。他們從小被逼著上好中學(xué)、好高中,找一個(gè)好工作、好配偶。但事實(shí)是競(jìng)爭(zhēng)雖然越來(lái)越激烈,但回報(bào)越卻來(lái)越少。今年6月,中國(guó)的青年失業(yè)率達(dá)到有史以來(lái)最高的19.3%。買房對(duì)年輕人來(lái)說(shuō)是一個(gè)越來(lái)越遙不可及的夢(mèng)想。2020年,中國(guó)的城市平均房?jī)r(jià)達(dá)到人均年收入的13.7倍,也就是說(shuō)買房的困難程度是美國(guó)的兩倍。“年輕人有了一種無(wú)助感,無(wú)論他們?nèi)绾闻ぷ鳎麄兿胍臇|西都是遙不可及的。”迪赫特瓦爾德說(shuō)。

有專家表示,“躺平”和“內(nèi)卷”不光只是網(wǎng)絡(luò)熱詞,而是正在整個(gè)中國(guó)社會(huì)蔓延。一些白領(lǐng)選擇辭掉高壓工作搬到農(nóng)村生活。還有專家認(rèn)為,中國(guó)生育率的下跌,至少有一部分原因,是因?yàn)橹袊?guó)年輕女性不愿意屈從于社會(huì)的壓力而生孩子。

Alarice公司的創(chuàng)始人阿什利·杜達(dá)內(nèi)洛克表示,要想通過(guò)宣傳“偷懶文化”吸引這些身心被掏空的年輕人,并不是一件容易的事情。不過(guò)很多在華的外國(guó)品牌都想吸引這部分年輕人,但結(jié)果卻是參差不齊。

去年,有一位叫利路修(Vladislav Ivanov)的俄羅斯男孩中國(guó)的一個(gè)音樂(lè)綜藝節(jié)目里火了,成了“躺平”運(yùn)動(dòng)的一個(gè)代言人。利路修在參加了節(jié)目后,千方百計(jì)想早點(diǎn)輸?shù)舯荣悾層^眾別投票給他,好打包行李回家休息。結(jié)果網(wǎng)友們愛(ài)上了他的“躺平”精神,偏偏投票不讓他下課,結(jié)果他足足在這個(gè)節(jié)目里待了十集,幾乎被網(wǎng)友逼著參加完了一整季的節(jié)目。

此后,普拉達(dá)(Prada)、古馳(Gucci)和芬迪(Fendi)等外國(guó)時(shí)尚品牌都找利路修來(lái)代言在中國(guó)的廣告。比如在美國(guó)綠箭公司(Wrigley)的一個(gè)廣告里,利路修無(wú)論是上班下班還是健身的時(shí)候都嚼著口香糖。這說(shuō)明這些品牌都想借“躺平”文化分一杯羹。

國(guó)潮

阿諾德·馬認(rèn)為,如果說(shuō)這一代中國(guó)年輕人是“躺平的一代”,這種說(shuō)法顯然不正確。通過(guò)萬(wàn)豪集團(tuán)的這次營(yíng)銷活動(dòng),他發(fā)現(xiàn)中國(guó)的年輕人未必都是躺平的,他們也想找到自己的激情,并以某一種方式去追求它。

他還表示,在萬(wàn)豪集團(tuán)的這次任務(wù)中,最難的部分,就是如何向年輕人推銷一個(gè)外國(guó)品牌。“以前,西方品牌在中國(guó)自帶一種高級(jí)感,但現(xiàn)在不是這樣了。”

隨著近年來(lái)中美摩擦不斷擴(kuò)大,以購(gòu)買國(guó)貨為榮的“國(guó)潮”正在興起,特別是在“Z世代”的年輕人中。麥肯錫公司(McKinsey)在2020年曾經(jīng)對(duì)15個(gè)城市的5,000人作過(guò)一項(xiàng)調(diào)查,結(jié)果顯示,2011年以來(lái),更愿意購(gòu)買國(guó)產(chǎn)而不是外國(guó)品牌的比例已經(jīng)由15%上升到了85%,而“國(guó)潮”的消費(fèi)主力就是“Z世代”。騰訊最近的一項(xiàng)調(diào)查也顯示,45%的“95后”年輕人經(jīng)常購(gòu)買有“國(guó)潮”元素的產(chǎn)品,而在90后和80后消費(fèi)者中,這一比例分別為38%和27%。

2021年3月,一些中國(guó)的年輕人以燒掉耐克鞋的方式,抗議耐克公司(Nike)在新疆棉問(wèn)題上的立場(chǎng)。就在今年8月,大量社交媒體用戶還威脅抵制士力架(Snickers),因?yàn)樵摴驹谝粍t外國(guó)廣告里稱中國(guó)臺(tái)灣地區(qū)是一個(gè)國(guó)家。就在“士力架事件”發(fā)生前不久,美國(guó)國(guó)會(huì)眾議院議長(zhǎng)南希·佩洛西竄訪了臺(tái)灣,造成了兩岸關(guān)系緊張局面急劇升高。士力架的美國(guó)母公司瑪氏箭牌(Mars Wrigley)在8月5日發(fā)表了一則道歉聲明,稱臺(tái)灣地區(qū)“是中國(guó)領(lǐng)土不可分割的一部分”。

博圣軒的營(yíng)銷總監(jiān)阿利森·馬爾姆斯滕說(shuō):“中國(guó)的‘Z世代’已經(jīng)以自己的方式‘覺(jué)醒’了。中國(guó)年輕人對(duì)外國(guó)影響力是持非常批判的態(tài)度的。”

因此,在中國(guó)的外國(guó)品牌絕不能忽視“國(guó)潮”的威力,從而輸給愛(ài)國(guó)的競(jìng)爭(zhēng)對(duì)手。因此,很多外國(guó)公司也正在與本地品牌和機(jī)構(gòu)開(kāi)展合作。

阿諾德·馬表示:“國(guó)潮有正宗性和民族性兩個(gè)特點(diǎn)。外國(guó)品牌要想做好這件事情,唯一的辦法就是與本土伙伴合作。”例如奧利奧(Oreo)與故宮博物院的合作就是一次成功的合作。

2019年,奧利奧和故宮博物院聯(lián)合推出了以皇室為主題的奧利奧餅干,包括綠茶、紅豆和荔枝玫瑰等口味——這些都是康熙皇帝喜歡的點(diǎn)心。奧利奧表示,這些新品牌上線首日就賣掉了76萬(wàn)盒,并且為它的天貓旗艦店帶來(lái)了26萬(wàn)新粉絲。

也有一些洋品牌,畫虎不成反類犬,消費(fèi)者一眼就看出這是假冒的“國(guó)潮”。

比如美國(guó)巧克力制造商德芙(Dove)也在2020年農(nóng)歷新年推出了故宮主題的巧克力。但網(wǎng)友們紛紛吐槽稱,這些巧克力幾乎沒(méi)有任何中國(guó)歷史元素,只不過(guò)是偽“國(guó)潮”。

Alarice公司的創(chuàng)始人阿什利·杜達(dá)內(nèi)洛克稱:“有些合作是非常膚淺的,或者對(duì)文化引用不當(dāng),這反而會(huì)危及品牌的聲譽(yù)。”

最后,迪赫特瓦爾德指出,外國(guó)品牌必須以謙卑的態(tài)度對(duì)待中國(guó)市場(chǎng)。

他表示:“你必須專門針對(duì)中國(guó)年輕人市場(chǎng)設(shè)計(jì)產(chǎn)品,這意味著你要真正了解他們想要什么。很多國(guó)際品牌都在投資收集這些市場(chǎng)情報(bào),但有時(shí)它們并未委托中國(guó)團(tuán)隊(duì)來(lái)制定這些戰(zhàn)略。”

阿諾德·馬認(rèn)為,西方品牌光靠認(rèn)知度就能夠占領(lǐng)市場(chǎng)的日子已經(jīng)一去不復(fù)返了。

他說(shuō):“你不能以為自己是一個(gè)歷史悠久的外國(guó)品牌,就以為自己可以予取予求,現(xiàn)在這樣只會(huì)讓人覺(jué)得你很傲慢。人們不在乎你是從哪兒來(lái)的,只在乎你現(xiàn)在在做什么。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:樸成奎

Last year, Marriott International tasked Arnold Ma with creating a marketing campaign for the Shanghai opening of Moxy, a hip, modern offshoot of the U.S. hotel giant geared towards younger guests.

In Marriott Moxy hotels in the U.S., the front desk doubles as a bar, and lobby furniture bears slogans like ‘pizza is my spirit animal.’ Marriott knew it had to localize Moxy to appeal to China’s Gen Z. It hired Ma, CEO of China-focused digital marketer Qumin, to sell the brand—energetic and lively—to China’s young consumers, who are known for being skeptical of foreign influences and for ‘lying flat’ to escape the rat race of China’s economy by doing as little as possible.

The project was a study in contradictions, but it was up to Ma’s Qumin team to make it work.

They started by conducting a sort of unofficial ethnography of China’s Gen Z and found that members of China’s Gen Z had an “innate confidence” in their own abilities and a desire to create. So Qumin enlisted a group of underground Gen Z artists with cult followings to paint the hotel’s interior and craft cocktails for the launch of China’s first Moxy hotel in Shanghai’s Hongqiao district. Local graffiti artists tagged the walls with robots and abstract images. A DJ played house music. There was a pit of pink and purple plastic balls and pillows specially designed for the opening plastered with pictures of guitars and red, floating lips.

An accompanying campaign on Douyin, China’s TikTok, called ‘Where Brave Starts,’ featured influencers who’d made Moxy-themed videos and inspired followers to make thousands of videos of their own. “We kind of had this pyramid effect where we got creators to make pieces for the hotel, which then could be turned into content,” says Ma.

The ‘Make Moxy Yours’ campaign generated “a phenomenal 420 million views and 5.98 million likes” on Chinese social media channels, says Jennie Toh, vice president of brand marketing for Marriott Asia Pacific. After the launch of the Shanghai Hongqiao location in June 2021, Marriott opened a second Moxy hotel in Shanghai and four others throughout the mainland. More locations are “in the pipeline,” Toh says.

Occupancy figures rose 500% at Moxy’s flagship Shanghai location in the weeks after the campaign. Marriott declined to say if that success continued this year amid tight COVID restrictions, but executives claim that the company’s business in China remains strong. “Many of [Marriott’s or its partners’] hotels are benefiting from increased volumes of domestic travel [in China], albeit some pauses when certain markets go into lockdown,” Marriott CEO Anthony Capuano said on an earnings call earlier August.

Marriott loved the marketing campaign’s results, even if its leaders didn’t fully comprehend how Ma generated them. “[A Marriott executive] was like, ‘Man, I don’t understand what’s happening in any of these videos,’” Ma says.

Foreign executives don’t have to see eye-to-eye with China’s Gen Zers to recognize their power. China’s 270 million Gen Zers make up 19% of the nation’s total population, a share that is set to grow to 27% by 2025, according to Chinese digital marketing agency Alarice. The spending power of China’s Gen Z is set to quadruple to $2.4 trillion from now until 2035, according to China Renaissance. But the quirks of Gen Z—their distaste for overwork and preference for local goods—defy generational shifts of the past. Western brands that want to remain relevant in the market of 1.4 billion have to rethink their China strategies and learn a new set of rules to crack China’s Gen Z code.

The disconnect

China’s Gen Z is not just indecipherable to foreign executives. Older generations of Chinese also struggle to understand a cohort that has grown up in a world of relative affluence and WeChat.

China’s Gen Z population was born between the years of 1997 and 2012, just as the country transformed from a plodding backwater into a global powerhouse. During that time, China’s economy expanded by a factor of eight, growing from the world’s seventh largest economy to second place. When the first Gen Zers were born in 1997, China’s economy was just starting to boom, and the country had a per capita GDP of $781. By 2007, when Gen Zers turned 10, China’s per capita GDP had more than tripled to $2,694. Gen Zers have only known China as an economic superpower, a trait distinguishing them from their elders whose working years coincided with China’s rise.

“It’s the biggest gap between any generation and another, probably anywhere in history,” says Ma.

Smartphones have worsened the disconnect, says Allison Malmsten, marketing director at Daxue Consulting. China’s Gen Zers are defined by their digital lives. “In the West, they’re kind of testing the waters with integrating social media and e-commerce,” she says. “But in China, they’ve already been doing this for a couple of years now… that means your social media time is more integrated with your shopping time, which is more integrated with showing off what you are buying, which is more integrated with hobbies.”

The gulf between Gen Z and older generations fuels movements like “l(fā)ying flat” and “involution”—a term that refers to the opposite of evolution and encourages people to become stagnant. Older generations were willing to log long hours to grow China’s GDP. Gen Z is struggling to see the payoff; China is already a top economy, and the rewards for their hard work have diminished.

This generation has grown up in a “super high-pressured environment,” where the intense competition of trying to get into the right middle school or high school is followed by an equally intense scramble to find the right job or spouse, says Zak Dychtwald, CEO of consultancy Young China Group. But the rat race doesn’t pay the way it used to. In June, China’s youth unemployment rate hit an all-time high of 19.3%. Buying a house is increasingly out of reach. In 2020, average housing prices in Chinese cities were nearly 13.7 times greater than average annual incomes, nearly double the ratio of the U.S. “There has been a feeling of helplessness that no matter how hard [Gen Zers] work or compete that the things that they want in life are out of reach,” says Dychtwald.

Lying flat and involution are not just online fodder, experts say; symptoms of passive resistance are popping up across Chinese society. Some white-collar workers are quitting high-stress jobs and moving to the countryside. Experts also attribute China’s falling birth rates, at least partly, to a desire among Chinese women to avoid societal pressures to have children.

Disaffected consumers promoting a “slacking culture” don’t make for easy marketing targets, says Ashley Dudanerok, founder of Alarice. But brands that do business in China are trying to reach them—with mixed results.

Last year, a Russian man named Vladislav Ivanov who goes by the stage name Lelush became a national star and a symbol of the lying flat movement after participating in a Chinese singing competition reality show. After Lelush signed up for the show, he purposely tried to lose and get himself voted off by deliberately singing poorly and pleading with viewers to not vote for him. Despite Lelush’s attempts to get kicked off, he made it through ten episodes, barely missing out on a spot in the show’s finale.

Fashion brands Prada, Gucci, and Fendi have all since featured Lelush in ad campaigns in China. Extra chewing gum, owned by American firm Wrigley, featured Lelush in a commercial in which he chews gum while he disinterestedly commutes to work, goes to the office, and works out at the gym. These brands are playing into the lying flat “slacking culture,” says Dudanerok.

Guochao or nationalistic buying

Ma argues that the ‘lying flat’ narrative about China’s Gen Z may be “blown out of proportion.” With the Marriott campaign, he found that Gen Zers were not necessarily apathetic; they just wanted to identify their passion and find a way to pursue it.

He says the hardest part of the Marriott assignment was selling young Chinese on a foreign brand. “Before Western brands were always seen as superior. That’s not the case anymore,” he says.

Indeed, guochao, or nationalistic buying, is rising in China amid a widening rift between the U.S. and Beijing; it’s especially popular among Gen Z consumers. Since 2011, the number of people who said they would buy a Chinese brand over a foreign one increased from 15% to 85%, according to a 2020 McKinsey survey of 5,000 people across 15 Chinese cities. And much of that rise is thanks to Gen Z. A Tencent survey recently showed that 45% of Chinese consumers born after 1995 often bought products that had guochao, or nationalistic elements in them, compared to 38% of consumers born in the 1990s and 27% born in the 1980s.

In March 2021, some young consumers burned Nike shoes to protest the company's stance on forced labor in China's contentious Xinjiang region. In August, social media users threatened to boycott Snickers candy bars after a Snickers ad shown outside mainland China referred to Taiwan as a country. The Snickers backlash occurred shortly after U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi's visit to Taiwan inflamed tensions between mainland China, Taiwan. Snickers' U.S. parent Mars Wrigley issued an apology on Aug. 5, declaring that Taiwan "is an inseparable part of Chinese territory."

"China's Gen Z is 'woke' in their own way," says Malmsten. "What is considered forward-thinking among Chinese Gen Z is being very critical of foreign influence."

Foreign brands can't ignore the guochao trend and lose out to patriotic competitors. Instead, companies based overseas are collaborating more with local brands and institutions.

"Guochao is all about authenticity and nationalism... the only way for foreign brands to do it well is to borrow authenticity and borrow nationalism through local partners," says Ma. He cited Oreo's collaboration with Beijing's Palace Museum, a historical museum housed inside the Forbidden City, as a successful partnership.

In 2019, Oreo and the Palace Museum created an imperial-themed line of Oreo cookies with flavors like green-tea cake, red-bean cake, and lychee-rose cake—the latter of which was a nod to the favorite snack of Qing Dynasty emperor Kangxi. Oreo claimed it sold 760,000 boxes of the new cookies online on the first day and attracted 260,000 new followers to its flagship store on Alibaba's TMall platform.

Other brands have clumsily played into Chinese patriotism, sparking backlash from consumers who can easily spot guochao imposters.

American chocolate maker Dove launched its own Forbidden City-themed box of chocolates for Chinese Lunar New Year in 2020. But internet users complained that the boxes barely featured elements from Chinese history and were just a ploy to capitalize on guochao.

"Collaborations that are viewed as superficial or that embrace improper cultural components endanger the brand's reputation," says Dudanerok.

Ultimately, Dychtwald says, foreign brands must approach the Chinese market humility.

"You have to create products that appeal to [China's Gen Z] market specifically, which means having an intimate understanding of what they want," he says. "Global brands are investing in market intelligence for that, but they're not always empowering the local Chinese team to actually develop the strategy."

The days of coasting on brand recognition alone are long gone, Ma says.

"You can't rely on the fact that you are a heritage foreign brand," says Ma. "That just seems really cocky these days... People don't care where you come from. People care about what you're doing right now."