幾十年來,超級碗(Super Bowl)一直是廣告領域里的“超級碗”。它是美國最盛大的舞臺,是最具分量的品牌,擁有最多的觀眾,而對于轉播超級碗的電視頻道來說,這一天是收入最高的一天。

2月共有9,640萬人觀看了這場比賽,以及中間插播的廣告。

但這一數字與接下來的數字相比則相形見絀。

同一時間,弗拉德和尼基?瓦什科托夫在他們的YouTube頻道上傳了多條視頻。身材瘦長、善于表達的8歲男孩弗拉德和天真可愛的5歲弟弟尼基在這些搞笑短視頻中做一些小孩子的游戲,比如說服媽媽給他們買一只寵物、搭建一個巨大的樂高房子、玩玩具車等等。

兩個男孩在2月最受歡迎的三條視頻的累計觀看量超過1.7億,而且這一數字還在不斷增加。

“Vlad and Niki”頻道在2018年開通。弗拉德在爸爸謝爾蓋的幫助下,發布了一條他和玩具狗和一些彩色積木做游戲的四分鐘視頻。

現在這個頻道在英語區YouTube上的訂閱用戶達到6,800萬,使兄弟兩人成為YouTube平臺上第三大網紅“創作者”。(謝爾蓋表示,兩兄弟在不同語言的平臺上共有1.73億訂閱用戶。)瓦什科托夫家人拒絕透露他們通過該平臺上插播的廣告獲得的收入分成,而且除此之外,這個頻道還給他們帶來了贊助合約、商品銷售、玩具許可權等。

但關注創作者行業的分析師表示,YouTube上的熱門頻道每年的收入可能達到3,000萬美元至5,000萬美元。按照這個水平,他們應該位于金字塔的頂端。

目前約有200萬創作者參與了YouTube的廣告項目,他們通常可以獲得55%的廣告收入分成。

現在是YouTube及其創作者蓬勃發展的時期。谷歌在2005年以16.5億美元的價格收購YouTube。YouTube去年公布的廣告收入為200億美元(分析師表示,除此之外,該公司還有數十億美元的產品訂閱收入,例如YouTube Premium會員等,但YouTube沒有披露具體財務數據)。

如果YouTube是一家獨立實體,它將是全球第四大數字廣告平臺,僅次于其母公司Alphabet、Facebook和亞馬遜。但真正讓華爾街垂涎不已的是它未來的成長空間。YouTube 2020年的收入比2019年增長了31%,而其母公司Alphabet的收入同期僅增長了12.8%。(但有一個事實會給亢奮的分析師潑一盆冷水:我們不清楚不斷增長的收入中有多少是利潤;從創作者分成到技術成本,YouTube會產生巨額支出。)

推動YouTube廣告業務繁榮的一個重要因素是傳統廣播和有線電視的衰落。市場跟蹤機構Convergence Research表示,2012年,付費電視觀眾約有1.01億個家庭,達到最高峰,但去年減少到7,600萬,預計到2025年將進一步減少一半以上。

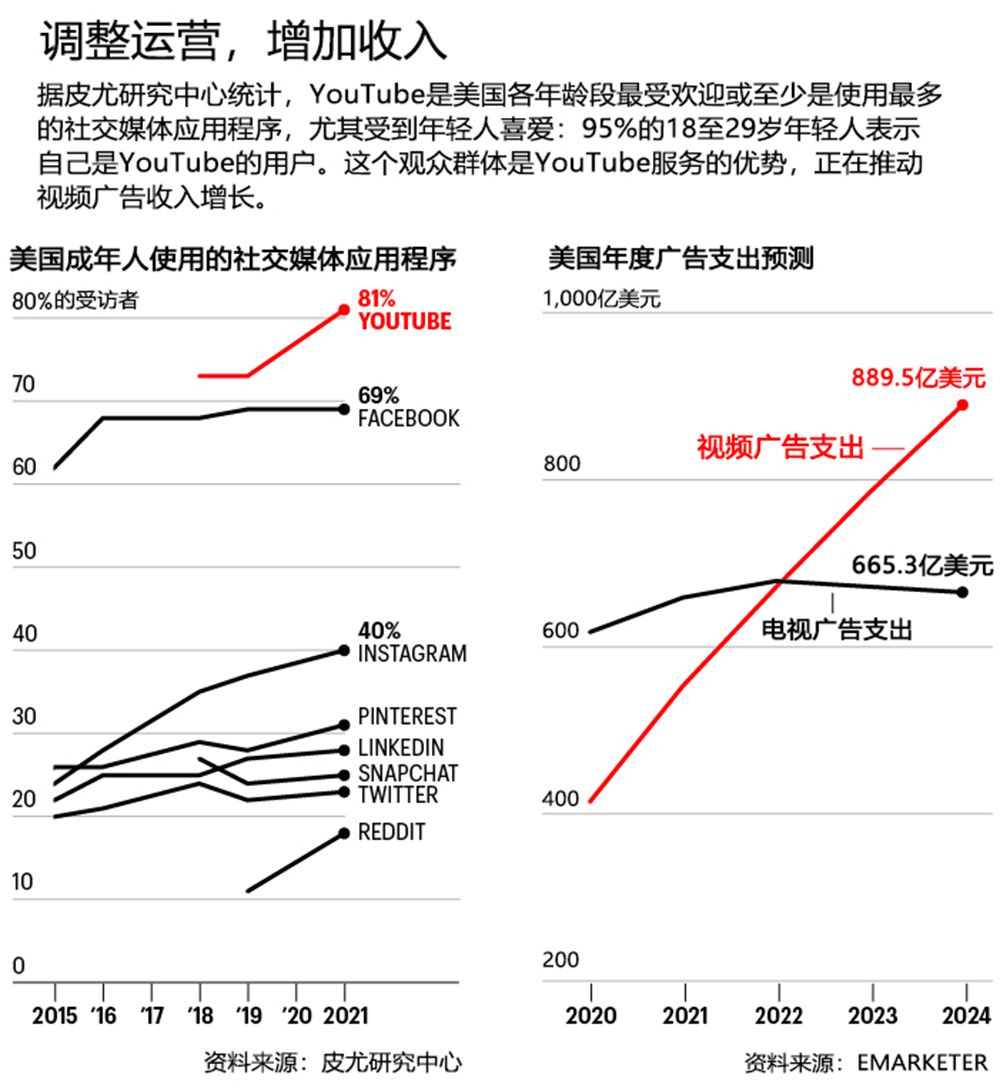

廣告支出與觀看人數息息相關。去年,電視廣告支出減少了12.5%,而視頻廣告支出增加了30.1%。事實上,eMarketer公司的分析師預測,到2023年,視頻廣告支出將首次超過電視廣告。

大型廣告公司GroupM的全球合作負責人基利?泰勒說:“所有人都在為大廣告商尋找新的投放廣告的機會。”她表示,隨著電視觀眾數量減少,“我們必須尋找其他途徑向大眾進行宣傳。”

而想要找到大量受眾,尤其是年輕人,YouTube是理想的選擇。

尼爾森最近的一項研究發現,YouTube是深受所有年齡段喜愛的社交平臺,50歲以下YouTube用戶的數量,始終高于相同年齡段傳統電視的觀眾數量。

4月,皮尤研究中心表示,81%的美國人使用YouTube,而使用第二大熱門社交平臺Facebook的美國人比例為69%。

所以,瓦什科托夫兄弟、費利克斯?謝爾貝格(網名PewDiePie)和莉莎?科希等YouTube網紅受Z世代追捧的程度,不亞于大牌運動員和名人,這不足為奇。

YouTube的主導地位在很大程度上取決于用手機觀看視頻的數以十億計的用戶。但它也在不斷擴大在客廳的影響。在客廳里,更多人觀看智能電視或者鏈接到Roku、Apple TV等機頂盒設備在大屏幕上看YouTube視頻。

YouTube表示,12月,美國有1.2億人通過電視觀看YouTube視頻,比九個月前增加了20%。而在觀看量最高的五種互聯網電視服務(Netflix、YouTube、Amazon Prime、Disney+和Hulu)中,只有YouTube和Hulu出售廣告。

*****

不斷擴張的廣告帝國是YouTube的首席執行官蘇珊?沃西基主管的領域。她是谷歌的第16位員工,在20世紀90年代加入該公司,從2014年開始負責該視頻服務的運營。

沃西基在帕洛阿爾托長大。她的父親是斯坦福大學的物理系主任,但沃西基堅稱她和同樣優秀的兩個姐妹(安妮創建了一家DNA分析公司23andMe,珍妮特則是一位人類學和流行病學博士),童年時代過得很普通,只是父母很重視她們是否有努力。

眾所周知,1998年,蘇珊在英特爾公司任職期間,把車庫租給了谷歌的聯合創始人謝爾蓋?布林和拉里?佩奇。她說,當時那樣做并不是因為她預感他們會取得成功。

在通過谷歌的Meet應用程序接受虛擬采訪時,她回憶道:“我需要租金支付住房按揭貸款。”

沃西基很早就看到了YouTube的潛力;她表示,是她最早力勸布林和佩奇收購剛誕生不久的YouTube平臺。沃西基曾經為谷歌創立了龐大的廣告業務,因此在收購完成后,她成為運營YouTube的不二之選。

不久,沃西基就發現了用戶創作的五花八門的內容和注重品牌形象的大廣告商,這兩者的組合很不穩定。沒有篩選出冒犯性內容的情況在YouTube時有發生,比如在種族主義、恐同和反猶太人視頻的旁邊投放廣告。

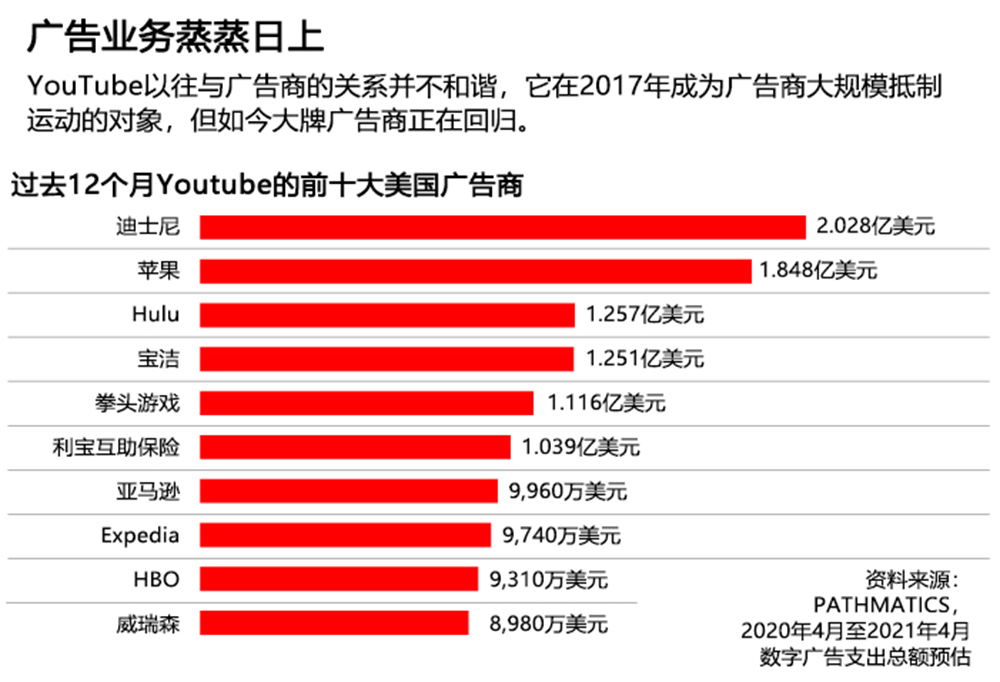

2017年,包括可口可樂、沃爾瑪、寶潔和星巴克在內的多家知名美國公司紛紛停止在YouTube投放廣告。

損失廣告收入、Alphabet股價受挫和公關危機,引起了YouTube的重視。

沃西基說:“我們必須從用戶和廣告商的角度解決這些問題……這對我們至關重要。”谷歌開始更多利用機器學習人工智能軟件來篩查不良內容,并招聘了數千名員工審核和評估可能違反公司服務條款的視頻。

最嚴重的危機已經結束,廣告商紛紛回歸。

當然,事實上,2017年導致YouTube被廣告商抵制的根本問題并沒有完全消失(例如QAnon、5G網絡陰謀論、疫苗微芯片等言論)。因此,隨著YouTube的發展,它必須同步升級其基礎設施,繼續清理各種有害的內容。

YouTube的策略分為四個部分,其首席產品官尼爾?莫漢將其稱為“4個R”。最明顯的是“刪除”(Removal),即找到并屏蔽最惡劣的內容。其次是“減少”(Reduce):利用YouTube強大的算法將疑似違規的視頻降級,以減少觀眾數量。(莫漢承認這個灰色地帶變得日益有挑戰性:“有許多內容很難確定是否違規,尤其是在虛假信息方面。”)

第三個R是指“力推”(Raising up)來自可信來源的視頻,尤其是與爭議話題有關的視頻。比如,5月13日,美國疾病預防控制中心(CDC)修改了佩戴口罩指南,當時YouTube的算法發現可能有虛假信息在傳播,于是該平臺挑選出一批有關這個話題的主流新聞報道,放在美國版頁面頂部的顯眼位置。最后一部分是“獎勵”(Reward),即推廣遵守規則的創作者的作品。

保證內容是安全的并且適合廣告商,這一點對YouTube變得至關重要,因此公司用于跟蹤該策略執行進展的指標,也包含在沃西基和其他高管的年度目標當中[在谷歌內部,這些“目標和關鍵成果”(OKR)是判斷成敗的終極指標],并越來越多地被公眾采用。

公司網站上的最新數據顯示,第一季度的違規觀看率從去年同期的0.17%至0.20%下降到0.16%至0.18%。違規觀看率用于統計被觀看的視頻中違反公司政策的比例。(令人意外的是,YouTube不愿意公布該網站上被觀看的視頻數量,但按照全球觀眾每天在該網站上花費的超過10億個小時來計算,即使0.16%的違規視頻也代表了較高的觀看量。)

大部分廣告商對YouTube所做的改進表示滿意。工藝品零售連鎖Michaels的首席營銷官羅恩?斯陶帕說:“我相信在這個平臺投放廣告是安全的。”Michaels從18個月前開始在YouTube投放廣告,廣告支出不斷增加。

迪克體育用品公司的媒體副總裁帕特里克?戴利稱,YouTube的“政策和工具絕大多數情況下都是有效的。”

有些廣告商表示,它們會聘請第三方評估其廣告是否出現在不恰當的內容旁邊。

威瑞森的數字營銷副總裁克里斯?保羅說:“我們不會讓合作伙伴自我評價。我們必須確保有獨立第三方進行驗證和核實。”

YouTube對內容的處理策略或許可以讓廣告商滿意,但許多觀察機構仍然心存疑慮。反誹謗聯盟的副總裁亞當?諾伊菲爾德表示,YouTube“沒有采取足夠的措施”減少騷擾和極端主義言論傳播。

“雖然YouTube公布了許多策略,也采取了一些適當措施,但該平臺上仍然存在嚴重問題。”批評者提到了與新冠疫情有關的虛假信息以及關于選舉舞弊的謊言等各種言論,證明YouTube依舊在放縱危險的視頻在其平臺上傳播。

沃西基和她的團隊成員都承認,該平臺依舊有改進的空間。沃西基說:“我們一直在努力完善。肯定有人總在想方設法濫用平臺,所以我們必須始終保持警惕。”

*****

廣告商、YouTube及其龐大的內容創作者之間這種獨特的三角關系,可能產生爭議,也可能帶來機會。

去年夏天,喬治?弗洛伊德在明尼蘇達州被一名警察謀殺引發全國抗議,當時YouTube上出現了無數視頻,人們在視頻中提供與這次犯罪有關的信息,或者分享自己遭遇警察暴力的經歷。

有黑人創作者承諾將其在YouTube平臺上的廣告收入捐贈給“黑人的命也是命”(Black Lives Matter)等組織,并鼓勵觀眾點擊廣告和重復觀看,以支持他們的做法。

但廣告商不愿意為這些重復點擊付費,它們向YouTube投訴,于是后者開始打擊這種行為。YouTube方面表示,將代替創作者向種族正義組織捐款,但這種做法已經對有些創作者造成了傷害。

提出這種想法的美妝博主佐伊?阿米拉批評YouTube的決定“令人失望”。她說:“我能夠理解它這樣做是為了維護與廣告商的關系。”但她認為另一方面,“YouTube應該讓觀眾自己決定參與的方式。”

除此之外,YouTube還在嘗試利用其對廣告商的影響力,鼓勵廣告商重新評估其策略,在增加廣告商業務的同時,可以支持以往被忽視的創作者和內容。

其中一個領域是說唱視頻。這個板塊在YouTube上很受歡迎,但大牌廣告商通常會避免在這個板塊投放廣告。YouTube試圖說服廣告商重新審視這類視頻,該公司稱全世界所有音樂視頻的前10名幾乎都是說唱藝人,并向廣告商承諾最新技術能夠過濾歌詞或圖像不恰當的視頻。

YouTube全球視頻解決方案副總裁、廣告合作事務的負責人黛比?溫斯坦稱:“如果你是廣告商,希望與觀眾和流行文化產生聯結,那么放棄說唱就是一大損失。”

雖然YouTube拒絕透露這方面工作的具體結果,但有跡象表明廣告商的態度正在發生改變。

GroupM的泰勒指出,在2020年夏季之前,許多公司將“黑人的命也是命”這個短語列為“禁用詞匯”,第三方軟件會根據“禁用詞匯”列表屏蔽公司的廣告,避免其與某一條視頻一同出現。但該平臺上到處都是談論“黑人的命也是命”的新聞和社會評論視頻,因此有部分廣告商同意將其從禁用詞匯名單中刪除。

泰勒說:“許多跨國品牌的自我反思和成熟令我備受鼓舞。”

*****

雖然所有人都在關注YouTube的內部問題,但它面臨的最大威脅可能來自該平臺以外。目前,YouTube是少數幾個出售廣告的流媒體平臺之一,但HBO Max已經表示很快將進軍這個領域,如果Netflix或迪士尼也跟進,這個領域不久就會變得競爭異常激烈。

在社交平臺方面,短視頻應用程序TikTok也是YouTube的一大威脅。現在,TikTok是硅谷的“熱門新事物”。TikTok和Instagram一直在積極推出新視頻功能,并為人們創造更多通過其應用程序變現的途徑,它們也是YouTube維持創作者忠誠度面臨的主要競爭對手。

為了留住優秀創作者,YouTube一直在努力增加變現方案。現在創作者可以在YouTube網站并通過其支付系統,出售月度會員、在線貼紙等數字商品以及實物商品等。未來YouTube將推出對可能從視頻中獲得較大價值的觀眾收取一次性費用的做法,類似于打賞功能。

YouTube分別于去年9月和今年3月先后在印度和美國新推出了不超過60秒的短視頻功能Shorts,每天吸引的觀看量已經達到65億。這種短視頻功能為創作者提供了一個創作簡單視頻的平臺(而且能夠幫助YouTube與TikTok競爭),因為創作者一直抱怨,為了維持頂流創作者的地位他們需要創作足夠多的內容,這讓他們不堪重負。YouTube一方面拿出1億美元,用于向短視頻創作者付費,同時也在構建支持新格式的廣告系統。

YouTube也在進行各種嘗試,努力為廣告商創造更多價值。例如,不久將大范圍推廣的一項措施是向廣告商開放谷歌商戶中心。該功能允許廣告商在相關內容中添加產品鏈接,例如當用戶在YouTube搜索“最好的棒球手套”時,他會看到視頻上出現一批手套廣告。

當然,對任何大型科技公司而言,尤其是在目前,監管才是最大的威脅。各國都在采取措施管制社交媒體,包括有國家提案要求內容托管方對任何危險的帖子或視頻承擔法律責任。

YouTube的部分批評者認為,這類監管是防止不良內容傳播的唯一途徑。紐約州立大學布法羅分校專門研究虛假信息的約塔姆?奧菲爾教授表示:“我認為我們不能夠指望私人公司拯救世界。我不信任它們……它們當然可以做得更好,只是它們需要這樣做的動機。”

沃西基顯然不認同這種觀點。有些政府提案可能導致非專業人士無法發布視頻,或者阻礙YouTube賴以生存的創作者經濟的發展。

她說:“我們希望與政府合作,確保他們做出對國民和社區有利的決策。但該計劃還沒有經過深思熟慮。”

對于可能出現的意想不到的后果,以及在事情沒有考慮周全的情況下可能發生的情況,YouTube當然有應對的經驗。所以,關于YouTube未來是否會朝著沃西基設想的方向發展,你需要點擊“訂閱”按鈕來一探究竟。(財富中文網)

助理報道:丹尼埃爾?阿布里爾

譯者:Biz

幾十年來,超級碗(Super Bowl)一直是廣告領域里的“超級碗”。它是美國最盛大的舞臺,是最具分量的品牌,擁有最多的觀眾,而對于轉播超級碗的電視頻道來說,這一天是收入最高的一天。

2月共有9,640萬人觀看了這場比賽,以及中間插播的廣告。

但這一數字與接下來的數字相比則相形見絀。

同一時間,弗拉德和尼基?瓦什科托夫在他們的YouTube頻道上傳了多條視頻。身材瘦長、善于表達的8歲男孩弗拉德和天真可愛的5歲弟弟尼基在這些搞笑短視頻中做一些小孩子的游戲,比如說服媽媽給他們買一只寵物、搭建一個巨大的樂高房子、玩玩具車等等。

兩個男孩在2月最受歡迎的三條視頻的累計觀看量超過1.7億,而且這一數字還在不斷增加。

“Vlad and Niki”頻道在2018年開通。弗拉德在爸爸謝爾蓋的幫助下,發布了一條他和玩具狗和一些彩色積木做游戲的四分鐘視頻。

現在這個頻道在英語區YouTube上的訂閱用戶達到6,800萬,使兄弟兩人成為YouTube平臺上第三大網紅“創作者”。(謝爾蓋表示,兩兄弟在不同語言的平臺上共有1.73億訂閱用戶。)瓦什科托夫家人拒絕透露他們通過該平臺上插播的廣告獲得的收入分成,而且除此之外,這個頻道還給他們帶來了贊助合約、商品銷售、玩具許可權等。

但關注創作者行業的分析師表示,YouTube上的熱門頻道每年的收入可能達到3,000萬美元至5,000萬美元。按照這個水平,他們應該位于金字塔的頂端。

目前約有200萬創作者參與了YouTube的廣告項目,他們通常可以獲得55%的廣告收入分成。

現在是YouTube及其創作者蓬勃發展的時期。谷歌在2005年以16.5億美元的價格收購YouTube。YouTube去年公布的廣告收入為200億美元(分析師表示,除此之外,該公司還有數十億美元的產品訂閱收入,例如YouTube Premium會員等,但YouTube沒有披露具體財務數據)。

如果YouTube是一家獨立實體,它將是全球第四大數字廣告平臺,僅次于其母公司Alphabet、Facebook和亞馬遜。但真正讓華爾街垂涎不已的是它未來的成長空間。YouTube 2020年的收入比2019年增長了31%,而其母公司Alphabet的收入同期僅增長了12.8%。(但有一個事實會給亢奮的分析師潑一盆冷水:我們不清楚不斷增長的收入中有多少是利潤;從創作者分成到技術成本,YouTube會產生巨額支出。)

推動YouTube廣告業務繁榮的一個重要因素是傳統廣播和有線電視的衰落。市場跟蹤機構Convergence Research表示,2012年,付費電視觀眾約有1.01億個家庭,達到最高峰,但去年減少到7,600萬,預計到2025年將進一步減少一半以上。

廣告支出與觀看人數息息相關。去年,電視廣告支出減少了12.5%,而視頻廣告支出增加了30.1%。事實上,eMarketer公司的分析師預測,到2023年,視頻廣告支出將首次超過電視廣告。

大型廣告公司GroupM的全球合作負責人基利?泰勒說:“所有人都在為大廣告商尋找新的投放廣告的機會。”她表示,隨著電視觀眾數量減少,“我們必須尋找其他途徑向大眾進行宣傳。”

而想要找到大量受眾,尤其是年輕人,YouTube是理想的選擇。

尼爾森最近的一項研究發現,YouTube是深受所有年齡段喜愛的社交平臺,50歲以下YouTube用戶的數量,始終高于相同年齡段傳統電視的觀眾數量。

4月,皮尤研究中心表示,81%的美國人使用YouTube,而使用第二大熱門社交平臺Facebook的美國人比例為69%。

所以,瓦什科托夫兄弟、費利克斯?謝爾貝格(網名PewDiePie)和莉莎?科希等YouTube網紅受Z世代追捧的程度,不亞于大牌運動員和名人,這不足為奇。

YouTube的主導地位在很大程度上取決于用手機觀看視頻的數以十億計的用戶。但它也在不斷擴大在客廳的影響。在客廳里,更多人觀看智能電視或者鏈接到Roku、Apple TV等機頂盒設備在大屏幕上看YouTube視頻。

YouTube表示,12月,美國有1.2億人通過電視觀看YouTube視頻,比九個月前增加了20%。而在觀看量最高的五種互聯網電視服務(Netflix、YouTube、Amazon Prime、Disney+和Hulu)中,只有YouTube和Hulu出售廣告。

*****

不斷擴張的廣告帝國是YouTube的首席執行官蘇珊?沃西基主管的領域。她是谷歌的第16位員工,在20世紀90年代加入該公司,從2014年開始負責該視頻服務的運營。

沃西基在帕洛阿爾托長大。她的父親是斯坦福大學的物理系主任,但沃西基堅稱她和同樣優秀的兩個姐妹(安妮創建了一家DNA分析公司23andMe,珍妮特則是一位人類學和流行病學博士),童年時代過得很普通,只是父母很重視她們是否有努力。

眾所周知,1998年,蘇珊在英特爾公司任職期間,把車庫租給了谷歌的聯合創始人謝爾蓋?布林和拉里?佩奇。她說,當時那樣做并不是因為她預感他們會取得成功。

在通過谷歌的Meet應用程序接受虛擬采訪時,她回憶道:“我需要租金支付住房按揭貸款。”

沃西基很早就看到了YouTube的潛力;她表示,是她最早力勸布林和佩奇收購剛誕生不久的YouTube平臺。沃西基曾經為谷歌創立了龐大的廣告業務,因此在收購完成后,她成為運營YouTube的不二之選。

不久,沃西基就發現了用戶創作的五花八門的內容和注重品牌形象的大廣告商,這兩者的組合很不穩定。沒有篩選出冒犯性內容的情況在YouTube時有發生,比如在種族主義、恐同和反猶太人視頻的旁邊投放廣告。

2017年,包括可口可樂、沃爾瑪、寶潔和星巴克在內的多家知名美國公司紛紛停止在YouTube投放廣告。

損失廣告收入、Alphabet股價受挫和公關危機,引起了YouTube的重視。

沃西基說:“我們必須從用戶和廣告商的角度解決這些問題……這對我們至關重要。”谷歌開始更多利用機器學習人工智能軟件來篩查不良內容,并招聘了數千名員工審核和評估可能違反公司服務條款的視頻。

最嚴重的危機已經結束,廣告商紛紛回歸。

當然,事實上,2017年導致YouTube被廣告商抵制的根本問題并沒有完全消失(例如QAnon、5G網絡陰謀論、疫苗微芯片等言論)。因此,隨著YouTube的發展,它必須同步升級其基礎設施,繼續清理各種有害的內容。

YouTube的策略分為四個部分,其首席產品官尼爾?莫漢將其稱為“4個R”。最明顯的是“刪除”(Removal),即找到并屏蔽最惡劣的內容。其次是“減少”(Reduce):利用YouTube強大的算法將疑似違規的視頻降級,以減少觀眾數量。(莫漢承認這個灰色地帶變得日益有挑戰性:“有許多內容很難確定是否違規,尤其是在虛假信息方面。”)

第三個R是指“力推”(Raising up)來自可信來源的視頻,尤其是與爭議話題有關的視頻。比如,5月13日,美國疾病預防控制中心(CDC)修改了佩戴口罩指南,當時YouTube的算法發現可能有虛假信息在傳播,于是該平臺挑選出一批有關這個話題的主流新聞報道,放在美國版頁面頂部的顯眼位置。最后一部分是“獎勵”(Reward),即推廣遵守規則的創作者的作品。

保證內容是安全的并且適合廣告商,這一點對YouTube變得至關重要,因此公司用于跟蹤該策略執行進展的指標,也包含在沃西基和其他高管的年度目標當中[在谷歌內部,這些“目標和關鍵成果”(OKR)是判斷成敗的終極指標],并越來越多地被公眾采用。

公司網站上的最新數據顯示,第一季度的違規觀看率從去年同期的0.17%至0.20%下降到0.16%至0.18%。違規觀看率用于統計被觀看的視頻中違反公司政策的比例。(令人意外的是,YouTube不愿意公布該網站上被觀看的視頻數量,但按照全球觀眾每天在該網站上花費的超過10億個小時來計算,即使0.16%的違規視頻也代表了較高的觀看量。)

大部分廣告商對YouTube所做的改進表示滿意。工藝品零售連鎖Michaels的首席營銷官羅恩?斯陶帕說:“我相信在這個平臺投放廣告是安全的。”Michaels從18個月前開始在YouTube投放廣告,廣告支出不斷增加。

迪克體育用品公司的媒體副總裁帕特里克?戴利稱,YouTube的“政策和工具絕大多數情況下都是有效的。”

有些廣告商表示,它們會聘請第三方評估其廣告是否出現在不恰當的內容旁邊。

威瑞森的數字營銷副總裁克里斯?保羅說:“我們不會讓合作伙伴自我評價。我們必須確保有獨立第三方進行驗證和核實。”

YouTube對內容的處理策略或許可以讓廣告商滿意,但許多觀察機構仍然心存疑慮。反誹謗聯盟的副總裁亞當?諾伊菲爾德表示,YouTube“沒有采取足夠的措施”減少騷擾和極端主義言論傳播。

“雖然YouTube公布了許多策略,也采取了一些適當措施,但該平臺上仍然存在嚴重問題。”批評者提到了與新冠疫情有關的虛假信息以及關于選舉舞弊的謊言等各種言論,證明YouTube依舊在放縱危險的視頻在其平臺上傳播。

沃西基和她的團隊成員都承認,該平臺依舊有改進的空間。沃西基說:“我們一直在努力完善。肯定有人總在想方設法濫用平臺,所以我們必須始終保持警惕。”

*****

廣告商、YouTube及其龐大的內容創作者之間這種獨特的三角關系,可能產生爭議,也可能帶來機會。

去年夏天,喬治?弗洛伊德在明尼蘇達州被一名警察謀殺引發全國抗議,當時YouTube上出現了無數視頻,人們在視頻中提供與這次犯罪有關的信息,或者分享自己遭遇警察暴力的經歷。

有黑人創作者承諾將其在YouTube平臺上的廣告收入捐贈給“黑人的命也是命”(Black Lives Matter)等組織,并鼓勵觀眾點擊廣告和重復觀看,以支持他們的做法。

但廣告商不愿意為這些重復點擊付費,它們向YouTube投訴,于是后者開始打擊這種行為。YouTube方面表示,將代替創作者向種族正義組織捐款,但這種做法已經對有些創作者造成了傷害。

提出這種想法的美妝博主佐伊?阿米拉批評YouTube的決定“令人失望”。她說:“我能夠理解它這樣做是為了維護與廣告商的關系。”但她認為另一方面,“YouTube應該讓觀眾自己決定參與的方式。”

除此之外,YouTube還在嘗試利用其對廣告商的影響力,鼓勵廣告商重新評估其策略,在增加廣告商業務的同時,可以支持以往被忽視的創作者和內容。

其中一個領域是說唱視頻。這個板塊在YouTube上很受歡迎,但大牌廣告商通常會避免在這個板塊投放廣告。YouTube試圖說服廣告商重新審視這類視頻,該公司稱全世界所有音樂視頻的前10名幾乎都是說唱藝人,并向廣告商承諾最新技術能夠過濾歌詞或圖像不恰當的視頻。

YouTube全球視頻解決方案副總裁、廣告合作事務的負責人黛比?溫斯坦稱:“如果你是廣告商,希望與觀眾和流行文化產生聯結,那么放棄說唱就是一大損失。”

雖然YouTube拒絕透露這方面工作的具體結果,但有跡象表明廣告商的態度正在發生改變。

GroupM的泰勒指出,在2020年夏季之前,許多公司將“黑人的命也是命”這個短語列為“禁用詞匯”,第三方軟件會根據“禁用詞匯”列表屏蔽公司的廣告,避免其與某一條視頻一同出現。但該平臺上到處都是談論“黑人的命也是命”的新聞和社會評論視頻,因此有部分廣告商同意將其從禁用詞匯名單中刪除。

泰勒說:“許多跨國品牌的自我反思和成熟令我備受鼓舞。”

*****

雖然所有人都在關注YouTube的內部問題,但它面臨的最大威脅可能來自該平臺以外。目前,YouTube是少數幾個出售廣告的流媒體平臺之一,但HBO Max已經表示很快將進軍這個領域,如果Netflix或迪士尼也跟進,這個領域不久就會變得競爭異常激烈。

在社交平臺方面,短視頻應用程序TikTok也是YouTube的一大威脅。現在,TikTok是硅谷的“熱門新事物”。TikTok和Instagram一直在積極推出新視頻功能,并為人們創造更多通過其應用程序變現的途徑,它們也是YouTube維持創作者忠誠度面臨的主要競爭對手。

為了留住優秀創作者,YouTube一直在努力增加變現方案。現在創作者可以在YouTube網站并通過其支付系統,出售月度會員、在線貼紙等數字商品以及實物商品等。未來YouTube將推出對可能從視頻中獲得較大價值的觀眾收取一次性費用的做法,類似于打賞功能。

YouTube分別于去年9月和今年3月先后在印度和美國新推出了不超過60秒的短視頻功能Shorts,每天吸引的觀看量已經達到65億。這種短視頻功能為創作者提供了一個創作簡單視頻的平臺(而且能夠幫助YouTube與TikTok競爭),因為創作者一直抱怨,為了維持頂流創作者的地位他們需要創作足夠多的內容,這讓他們不堪重負。YouTube一方面拿出1億美元,用于向短視頻創作者付費,同時也在構建支持新格式的廣告系統。

YouTube也在進行各種嘗試,努力為廣告商創造更多價值。例如,不久將大范圍推廣的一項措施是向廣告商開放谷歌商戶中心。該功能允許廣告商在相關內容中添加產品鏈接,例如當用戶在YouTube搜索“最好的棒球手套”時,他會看到視頻上出現一批手套廣告。

當然,對任何大型科技公司而言,尤其是在目前,監管才是最大的威脅。各國都在采取措施管制社交媒體,包括有國家提案要求內容托管方對任何危險的帖子或視頻承擔法律責任。

YouTube的部分批評者認為,這類監管是防止不良內容傳播的唯一途徑。紐約州立大學布法羅分校專門研究虛假信息的約塔姆?奧菲爾教授表示:“我認為我們不能夠指望私人公司拯救世界。我不信任它們……它們當然可以做得更好,只是它們需要這樣做的動機。”

沃西基顯然不認同這種觀點。有些政府提案可能導致非專業人士無法發布視頻,或者阻礙YouTube賴以生存的創作者經濟的發展。

她說:“我們希望與政府合作,確保他們做出對國民和社區有利的決策。但該計劃還沒有經過深思熟慮。”

對于可能出現的意想不到的后果,以及在事情沒有考慮周全的情況下可能發生的情況,YouTube當然有應對的經驗。所以,關于YouTube未來是否會朝著沃西基設想的方向發展,你需要點擊“訂閱”按鈕來一探究竟。(財富中文網)

助理報道:丹尼埃爾?阿布里爾

譯者:Biz

FOR DECADES, the Super Bowl has been, well, the Super Bowl of the advertising world. The biggest stage, the biggest brands, the biggest audience, and, for the channel that hosts it, the biggest payday. In February, 96.4 million people tuned in to watch the big game and the ads that ran along with it.

Also in February, Vlad and Niki Vashketov posted a handful of videos to their YouTube channel. The short, manic clips show Vlad, a gangly and expressive 8-year-old, and his doeeyed 5-year-old brother, Niki, doing kid stuff: persuading their mom to get them a pet, building a giant Lego house, playing with toy cars. Cumulatively, the boys’ three most popular videos of the month have amassed more than 170 million views—and counting.

The Vlad and Niki channel, which launched in 2018 when Vlad, with the help of his dad, Sergey, posted a four-minute video of Vlad playing with a toy dog and some colored blocks, now has 68 million subscribers on English-language YouTube, making the brothers the third most popular “creators” on the platform. (Globally, Sergey says, the boys have a total of 173 million subscribers in various languages.) The Vashketov family declines to say how much it makes from its share of the revenue from the ads that play against its videos on the platform—not to mention the brand sponsorship deals, merchandise sales, and toy licensing rights the channel has birthed. But analysts who track the creator industry say that, all in, the top channels on YouTube are earning $30 million to $50 million per year. That puts them at the pointy end of the pyramid of some 2 million creators who participate in YouTube’s advertising program and typically get a 55% cut of the ad revenue they generate.

It’s boom times for YouTube and its creators. The Google-owned service, bought for just $1.65 billion in 2005, reported ad revenue of $20 billion last year (plus what analysts say are billions of dollars more from subscriptions to products like YouTube Premium, the financial details of which the company doesn’t disclose). Some context: If YouTube were a stand-alone entity, that would make it the world’s fourth-largest seller of digital ads, after its parent company, Alphabet, Facebook, and Amazon. But what really has Wall Street salivating is the question of just how big it might get. YouTube’s 2020 revenue was up 31% from 2019, compared with a 12.8% increase for its parent, Alphabet. (One note that puts something of a damper on analysts’ exuberance: We still don’t know how much of that growing pool of money is profit; between creator payouts and tech costs, YouTube has significant expenses.)

A big factor driving YouTube’s ad ascendance is the decline of traditional broadcast and cable TV. After peaking at almost 101 million households in 2012, the pay TV audience dropped to 76 million last year and is forecast to shrink to less than half that by 2025, according to market tracking firm Convergence Research. Ad dollars follow the eyeballs. Spending on TV advertising dropped 12.5% last year, while video ads surged 30.1%. Indeed, the analysts at eMarketer are predicting that the amount spent on video advertising will surpass that of TV for the first time by 2023.

“Everyone is looking for new ad opportunities for big advertisers,” says Kieley Taylor, global head of partnerships at mega ad agency GroupM. As the TV audience shrinks, she says, “we have to find other ways to talk to a lot of people.”

If you want to reach a lot of people—and especially young people—YouTube is the place to do it. It’s the most popular social platform among almost all age groups, and the number of people under 50 using YouTube regularly tops the number of people in that same cohort who are watching traditional TV, a recent study by Nielsen concluded. In April, Pew Research said 81% of Americans use YouTube, compared with 69% for Facebook, the second most popular option. It’s no wonder then that for Gen Z, YouTube stars like the Vashketov brothers, Felix Kjellberg (a.k.a. PewDiePie), and Liza Koshy are as recognized and admired as big-name athletes and celebrities.

For most of its life, YouTube’s dominance has depended on billions of mobile phone users watching videos. But it’s increasingly a force in the living room, where more people are watching smart TVs or connecting Roku, Apple TV, and other set-top boxes to watch YouTube on a big screen. YouTube said 120 million people in the U.S. watched via a TV in December, up 20% from nine months earlier. And of the top five most watched services on connected TVs—Netflix, YouTube, Amazon Prime, Disney+, and Hulu—only YouTube and Hulu sell ads.

*****

THIS GROWING ad empire is the domain of YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki, employee No. 16 at Google back in the 1990s, who has overseen the video service since 2014.

Growing up in Palo Alto, her dad was the chairman of the Stanford University physics department, but Wojcicki insists she and her equally formidable sisters—Anne started DNA analysis company 23andMe, and Janet is a Ph.D. anthropologist and epidemiologist—had a pretty normal childhood, though hard work was highly valued. Later, in 1998, while working at Intel, Susan famously rented her garage to Google cofounders Sergey Brin and Larry Page. It wasn’t because she had a clue they would be so successful, she says. “I wanted the rent because I needed the money to pay my mortgage,” she recalls during a virtual interview held via Google’s Meet app.

Wojcicki saw YouTube’s potential early; she says she was the first person to urge Brin and Page to buy the fledgling platform. And once they did, her background building out Google’s massive ad business made her the obvious candidate to run it.

But it didn’t take long for Wojcicki to discover just how volatile a mix user-generated videos and big-name, image-conscious advertisers could be. YouTube repeatedly failed to filter out offensive content—effectively putting ads against racist, homophobic, and anti-Semitic videos. And in 2017, a who’s who of corporate America, including Coca-Cola, Walmart, Procter & Gamble, and Starbucks, pulled their ad dollars.

The trifecta of lost ad money, a hit to Alphabet’s stock price, and a PR mess got YouTube’s attention.“We needed to work through those issues and to solve them in a way that worked for our users and our advertisers … That was critical for us,” says Wojcicki. Google expanded the use of its machine-learning A.I. software to screen for toxic content and hired thousands of workers to find and assess videos that might violate the company’s terms of service. The worst of the crisis passed, and advertisers trickled back.

The reality, of course, is that the underlying issues that sparked that 2017 boycott have never entirely vanished (see: QAnon, 5G conspiracy theories, vaccine microchips). And so, as YouTube has grown, so has the infrastructure it has created to clean up its sludge-filled gutters. Today the system has four components—which chief product officer Neal Mohan describes as the “Four R’s.” The most visible is “removal”—finding and spiking the most egregious content. Next comes “reduce”: shrinking the audience of borderline videos by downgrading them with YouTube’s all-powerful algorithm. (Mohan admits this gray area is a growing challenge: “There’s a lot of content out there that is very hard to categorize as crossing the line or not, particularly in the realm of misinformation.”) The third R stands for “raising up” videos from trustworthy sources, particularly on controversial topics. For instance, when the CDC issued revised guidance for wearing masks on May 13, YouTube’s algorithms detected a potential for the spread of misinformation and curated a group of mainstream news reports on the topic, which it gave a prominent spot near the top of U.S. feeds. The final plank of the strategy is “reward”—i.e., promote the videos of creators who follow the rules.

Keeping YouTube’s content safe—and therefore advertiser friendly—has become so critical that metrics the company uses to track its progress are included in the annual goals of Wojcicki and her top execs (these “Objectives and Key Results,” or OKRs, are the ultimate arbiters of success and failure inside the Googleplex) and, increasingly, are available to the public online. According to the latest data on the company’s site, the violative view rate—which measures the percentage of watched videos that violated the company’s policies—was between 0.16% to 0.18% in the first quarter, down from 0.17% to 0.20% a year earlier. (YouTube is surprisingly coy about the volume of videos watched on its site, but with more than a billion hours consumed per day, it’s fair to say that even 0.16% represents quite a lot of views.)

For the most part, advertisers say they are impressed with YouTube’s progress. “I’m pretty confident that we are in a safe place,” says Ron Stoupa, chief marketing officer at art-supply chain Michaels, which has been increasing spending with YouTube since it started advertising on the service 18 months ago. YouTube’s“policies and tools work as intended the vast majority of the time,” adds Patrick Daley, vice president of media at Dick’s Sporting Goods.

Some advertisers note that they hire outside companies to assess whether their spots are running alongside inappropriate content.“What we don’t do is allow our partners to check their own homework,” says Chris Paul, vice president of digital marketing at Verizon. “We have to make sure there’s an independent party giving us verification and validation.”

But while ad buyers may be feeling good about YouTube’s handle on its content, many watchdogs remain unconvinced. YouTube “has not taken enough steps” to reduce harassment and the spread of extremism, says Adam Neufeld, vice president of the Anti-Defamation League. “While they’ve announced various efforts and taken modest steps, these are both still massive problems.” Critics point to everything from COVID-19 misinformation to lies about election fraud as evidence that YouTube is still allowing dangerous videos to circulate on its platform.

Wojcicki and members of her team allow that there’s still a way to go. “It’s something we’ll always be working on,” the CEO says. “There will always be the potential of people looking for ways to abuse the platform, and that’s why we need to make sure that we’re vigilant at all times.”

*****

THE UNIQUE three-pronged relationship between advertisers, YouTube, and its vast network of creators can create both controversy and opportunity. Last summer, when the murder of George Floyd by a Minnesota police officer sparked nationwide protests, YouTube was awash in videos providing information about the crime and about the experiences of other victims of police brutality. Some Black creators on the site had pledged to donate their ad profits to organizations like Black Lives Matter and were encouraging viewers to click on their ads and watch them over and over as a way to show their support. Advertisers, unhappy about paying for these repetitive clicks, complained, and YouTube cracked down on the behavior. The company says it replaced the donations with its own contributions to racial justice organizations, but for some creators the damage was already done.

Beauty blogger Zoe Amira, who came up with the idea, calls the decision “disappointing.” “I guess I understood that it was in defense of their relationship with their advertisers,” she says, adding, on the other hand: “It should be left up to the watchers how they engage.”

In other instances, the company has attempted to use its clout with advertisers to encourage them to reassess their strategies in a way that could both boost their business and support creators and content that’s been overlooked in the past. One such area is hip-hop videos, a popular YouTube segment that big advertisers have historically avoided. YouTube pitched advertisers to reexamine the genre, noting that virtually every music video top 10 list around the world is dominated by hip-hop artists and pledging that the latest technology could filter out videos with inappropriate lyrics or images. “If you’re an advertiser and you want to be connecting with audiences and relevant in culture, not being in hip-hop is a big miss,” says Debbie Weinstein, VP of video global solutions at YouTube who oversees ad partnerships.

While YouTube declined to share any details about the results of the effort, there is some suggestion that advertisers are starting to evolve. Until the summer of 2020, many companies included the phrase Black Lives Matter on their list of“banned words”—terms that thirdparty software uses to block their ads from appearing against a video, says GroupM’s Taylor. But as the platform filled with news and social commentary videos citing BLM, some of those advertisers agreed to strike it from their list, she says: “I’m encouraged by the self-reflection and maturation I see with many multinational brands.”

*****

FOR ALL ITS FOCUS on internal issues, perhaps the biggest threats to YouTube’s future come from the world beyond its platform. At the moment, it’s one of the few streamers to accept ads, but HBO Max has said it plans to go that route soon, and if Netflix or Disney ever decide to follow suit, the space could get crowded fast. On the social side, the same could be said of TikTok, the short-form video app that currently wears Silicon Valley’s “hot new thing” mantle. TikTok and Instagram, which has been aggressively rolling out new video features and additional ways for people to make money on the app, are also major risk factors when it comes to maintaining the creators’ loyalty.

To keep the people who make its videos engaged, YouTube has been focused on expanding monetization options. Already, creators can sell monthly memberships, digital goods like online stickers, and merch—all from within their YouTube sites and via YouTube’s payments system. Nextup: a way to collect one-time payments, like a tip jar, for viewers who may derive a lot of value from a video.

YouTube’s new 60-seconds-or-less video feature, Shorts, which debuted in India in September and in the U.S. in March, is already attracting 6.5 billion views per day. The snack-size option gives creators, who have complained that the demands of making enough content to remain a top YouTuber can be exhausting and overwhelming, a forum to create simpler videos (and, yes, helps YouTube challenge TikTok). YouTube set up a $100 million fund to pay creators for making shorts while it gets its ad systems up and running in the new format.

YouTube has also been experimenting with ways to offer more value to advertisers. One such trial soon to be rolled out more broadly is access to the Google Merchant Center. The feature allows advertisers to place links to their products above relevant content, so users who search YouTube for, say, “best baseball glove” will see a bunch of glove ads hovering above the video.

Of course, for any Big Tech player, the ultimate threat, especially right now, is regulation. Efforts are under way around the globe to crack down on social media, including proposals that would hold content-hosting companies legally liable for any dangerous posts or videos.

Some of YouTube’s critics see such regulation as the only way to curb the spread of toxic content. “I don’t think we should expect private companies to save the world,” says University at Buffalo professor Yotam Ophir, who studies misinformation. “I don’t trust them … They can do much better, but they need the incentives to do so.”

Wojcicki obviously disagrees. Some proposals could make it impossible for amateurs to post videos or otherwise handicap the creator economy that underpins her company.

“We want to work with governments to make sure that they’re doing what’s right for citizens and communities,” she says. “But it might not have been thought through.”

YouTube has certainly had its share of experience with unintended consequences and what can happen when things might not have been thought all the way through. So, as to whether its future will follow the path Wojcicki wills, or something quite different—you’ll have to smash that “subscribe” button to find out.

Additional reporting by Danielle Abril