在二月的一個下雪天,克里斯汀·梅耶突然意識到自己必須親自負責賓州的疫苗接種工作。

內科醫學醫師梅耶在賓州費城郊區的艾克斯頓擁有一家20000病患的醫院。數周以來,他一直在接聽病患的電話,這些病患擁有注射新冠疫苗的資質,但無法在藥房、醫生辦公室,或通過當地衛生部門以及州疫苗信息網站進行預約。大多數病患的歲數都超過了75歲,而且很多人難以通過各大系統在線進行注冊,因為這些系統對于科技設備操作的熟練度有很高的要求。

當暴風雪來臨時,梅耶取消了個人就診預約,并要求其醫師和員工在日間幫助病患注冊疫苗接種。她在其醫院的Facebook頁面上發布了貼文,在兩個小時內,有1200人向她的辦公室發送郵件尋求幫助,醫院服務器也因此而癱瘓。不久之后,梅耶在Facebook上創建了一個由志愿者經營的匹配服務,以便讓高齡人士或其孩子或鄰居,獲取找尋接種服務的幫助。截至3月底,這個組織的成員超過了6萬人(包括在賓州長大、身為記者且嘗試幫助其當地父母接種疫苗的我本人)。當時,很少有用戶在等待州發布的消息:論壇上討論的內容全是沃爾格林(Walgreens)、CVS、Rite Aid和其他藥房什么時候才會批量公布接種預約機會,以及如何最為高效地使用其通常令人抓狂的預約網站。

梅耶通過視頻向《財富》雜志透露:“說真的,疫苗接種事務讓我感到心力交瘁。”她的語速和手勢逐漸加快,并透露出一種沮喪情緒。“我把所有的希望和所有病患的希望都寄托在了衛生部門的身上,因為事情本該如此,然而這個流程出了問題。”

梅耶和數百萬賓州民眾意識到,賓州的疫苗接種問題遠非令人困惑的注冊流程那么簡單。擁有超過2.48萬家醫院的賓州是全美新冠疫情死亡人數排名第五的州,同時也是美國疫苗接種問題最嚴重的州之一。《貝克爾醫院評論對疾控中心數據的分析顯示,在1月底,賓州收到了近200萬劑疫苗,但僅接種了42%,在美國排名第49位,僅位于阿拉巴馬之前。該州240萬老年易感人群一直在想方設法獲取疫苗接種服務,然而,該州卻向兒科醫院發送了1.2萬劑疫苗,但大多數兒童都不宜接種。衛生部門隨后發出警告,因與提供商的溝通有誤,有10多萬民眾可能不得不重新調整其接種第二針Moderna疫苗的日期。

與此同時,《費城詢問報》的一項分析發現,相對于該州一些罕有人居住的農村地區,公共衛生機構向費城郊區——也就是梅耶的醫院所在地250萬居民——發放的人均疫苗數量少得多。一位州發言人對分析的方法表示質疑,但地方官員對發現結果表示贊同:在擁有56.5萬人的特拉華郡,郡議會副主席莫妮卡·泰勒說,曾幾何時,該郡“每周僅獲得1000劑疫苗,聽起來更像是電影《饑餓游戲》。”

賓州疫苗接種問題反映了眾多其他大型種族和社會經濟形態多樣化的州在應對這個超大型復雜流程時所遇到的困境。這個全國性的舉措要求在各個不對等的團隊之間開展前所未有的協調工作,這些團隊包括在這個充滿諷刺意味的總統過渡過程中耗費了數月時間的聯邦政府、資金窘迫的州和當地政府,以及由大型醫療服務提供商、小型診所以及美國財富500強藥房和百貨連鎖店拼湊起來的網絡,它們都在疲于應對不斷變化——通常是相沖突的分配和資質法規。

然而,賓州的疫苗接種問題尤為突出,其中一些是自身的問題。與其他州不一樣的是,賓州拒絕創建一個集中化的疫苗接種系統,而是讓居民個人來承擔疫苗接種預約這個異常復雜的難題。州與地方領導人之間存在的各種官僚主義、配送問題以及沖突進一步放慢了疫苗接種進程,將各自為政的風險暴露無遺。截至3月底,賓州疫苗接種的多個指標均有所改善。然而,該州未能有效地照顧到那些最為脆弱的人群,包括黑人和拉美裔居民。

反復出現的問題讓醫生、地方官員和公共衛生專家對繁瑣的手續以及協調的缺乏感到失望。匹茲堡黑人平等聯盟成員、匹茲堡大學醫學中心 McKeesport醫療系統家庭醫學項目主任特雷西·康提說:“事實在于,賓州沒有一個集中化的流程,這意味著人們只能依靠各個組織自行其是,并寄希望于這種模式能夠奏效。它帶來了諸多的不確定因素,而且讓人沮喪不已。”

賓州官員也承認存在上述問題。衛生局局長阿里森·畢姆向《財富》透露,賓州經歷了“死亡審判月。我們還有很多要改善的地方,但我們唯一希望的就是繼續前行。”

賓州最引人注目的疫苗丑聞超出了該州的管轄范圍,但它依然充斥著整個疫苗接種過程。1月,從聯邦政府直接獲得疫苗供應的費城讓一家未經證實的初創企業Philly Fighting COVID來經營其首個大規模疫苗接種診所。該公司創始人安德烈·多羅辛是德雷塞爾大學22歲的神經科學畢業生,他在疫情初期成為了當地的創業英雄,當時,他與朋友一道用3D打印技術為當地醫院打印面罩。隨后,他的初創企業(一開始是一家非營利性機構)贏得了費城衛生部門19.4萬美元的合約,在服務低下的城市周邊經營新冠病毒測試站點。

然而,公共媒體機構WHYY開展的一項調查稱,當費城要求該公司接手城市的疫苗接種服務診所時,這家公司突然拋棄了其位于黑人和拉美裔聚居地的測試站點。WHYY還報道稱,這家初創企業在沒有通知該市官員的情況下,注冊了一家盈利公司。為了完成其從英雄到惡棍的公開轉型,多羅辛被人發現(后自己承認)將疫苗帶回家供朋友注射。當時,有資質的費城民眾卻被拒之其診所門外。(多羅辛通過一名發言人表示,拒絕對此置評。該發言人還稱,“我們沒有同時開展測試和疫苗接種服務的資源”,但“事后我們認為停止測試是一個錯誤”。)

賓州大學護理學院副教授阿里森·布特海姆(新冠疫情科學專家聯合組織Dear Pandemic的聯合創始人)說:“我希望看到地方、郡和州層面的政府都能正確行事。在另一個宇宙,Philly Fighting COVID本應成為費城的一道最靚麗風景線。”

費城的檢察長亞歷山大·德桑提斯在3月發表的一篇報道稱,然而在當前的宇宙,費城的計劃“為城市帶來了很大的風險。”(該市衛生部門的一位發言人拒絕置評。)

依然在調查這個問題的德桑提斯說:“我們的政府倉促行事,試圖迅速對這個問題做出響應。這是個有問題的流程。”

這樁丑聞是賓州早期的丑事,它凸顯了一個在全美普遍存在的問題:政府缺乏有經驗的疫苗接種合作方。這項業務明顯應該是醫院和大型醫療機構提供商的工作,但這些機構自身也存在不少問題。疫情加劇了其中期預算和人手短缺問題。總的來看,大型醫療系統去年每天的損失高達近10億美元。費城一家頂級醫院的高級醫師稱:“前往社區注射疫苗的成本非常昂貴,這個過程需要大量的物流,同時還需要空間和招聘人手,而且醫療系統還不一定能賺到錢。”

由聯邦資助的社區醫療中心可能最適合給少數族裔和服務低下的人群接種疫苗,但這些群體稱,擴張這一服務的前提就是政府給他們分配更多的疫苗。

填補這一空白的是那些大型零售連鎖藥店,它們在此前每年令人不安的流感疫苗接種過程中積累了大量的經驗。巴克萊銀行(Barclays)稱,僅沃爾格林和CVS預計今年就會接種全美約25%的新冠疫苗。這些連鎖店在交付疫苗方面還擁有更加強勁的經濟動力。它們預計疫苗接種本身將帶來營收增長:這些收入來自于政府或保險公司支付的每次注射費用;來自于向進店注射的客戶推銷更多的物品;來自于因營銷目的而收集的客戶數據。這些連鎖店還稱,農村和種族多元化人群更容易接觸到這些連鎖店。CVS Caremark首席醫療官斯瑞·查古圖魯稱,85%的美國民眾居住在CVS藥房10英里范圍之內,而且稱該公司在“店面位置的選擇方面曾進行過一番深思熟慮”,尤其在決定每個州的哪些藥房能夠獲得疫苗供應時十分注重平等性。

在賓州,協調這些合作伙伴的速度尤其緩慢,部分原因在于領導的更換。1月19日,拜登總統任命賓州衛生部部長蕾切爾·萊文擔任美國衛生部助理部長。這一任命是歷史性的:兒科醫生萊文隨后成為了美國參議院首位公開身份的跨性別官員。然而,此舉卻讓萊文的家鄉州賓州感到越發困惑。

州長湯姆·沃爾夫任命其時任副幕僚長阿里森·畢姆擔任賓州衛生部代理部長。畢姆曾一直參與制定該州的疫苗策略,但她向《財富》透露,自己在應對疫苗供不應求的局面時已經習慣了“缺乏必要規劃”的做法,以及隨之而來的疫苗分配“缺乏控制”的現象。(萊文的知情人士稱,這位性格外向的部長“采取了一切可行的辦法來制定一個強有力的疫苗接種計劃”,但“毫無疑問的是,初期階段過后還需要對其進行改進。”)

沃爾夫和畢姆已經創建了一個兩黨立法工作組,得到了一些地方提供商的贊許,他們認為此舉提升了疫苗接種的溝通頻率和信息清晰度。賓州社區醫療中心協會政策與合作伙伴關系主任埃瑞克·吉爾說:“溝通頻率在過去4-5周中增加了10倍。”賓州社區醫療中心的成員致力于為近100萬得不到足夠服務的居民提供醫療服務。然而,“此舉并未改變這個大問題。每個人都在詢問和索要疫苗,但我們手頭就是沒有疫苗。”

2月,該州還與波士頓咨詢集團(Boston Consulting Group)簽署了一項價值1160萬美元的合約,幫助改善其疫苗分發服務。該集團曾幫助賓州精簡了畢姆所稱的“笨重的提供商網絡”,該網絡由獲得疫苗配送的醫生和藥房構成。同時,波士頓咨詢集團還升級了畢姆口中“異常神秘”的數據報告流程,并幫助畢姆解決了“需求大潮”問題,因為當時賓州曾發出警告,有10萬居民可能無法及時獲得其Moderna疫苗的第二針注射。(賓州援引了疾控中心的指引,要求接受第二針疫苗注射的居民等待高達42天,而不是通常的28天。)

畢姆說:“我們一直在搭建最根本的基礎設施,同時還得應對這些緊急情況。”如今,“我們讓形勢變得更加緊迫。”

自初期的失利之后,賓州也取得了一些進步。截至3月25日,賓州在全美大眾疫苗分發領域已經躋身前25之列。疾控中心稱,超過81%的供應得到了注射,超過了全美78%的平均水平,其中28%的州居民已經獲得了至少一針疫苗注射。3月31日,畢姆宣布,費城之外的所有成人在4月19日之后都可以注射疫苗(不過,城市中的居民可能得等到5月1號之后)。

然而此次疫苗接種工作在一些社區做得并不夠深入,尤其是有色人種社區,而這些人群受疫情的影響尤為嚴重。美國疾控中心稱,截至3月中旬,向費城以外地區提供的賓州疫苗僅有3%流向了黑人居民,而黑人卻占到了該州非賓州當地人人口的7.5%。類似的不一致性也影響了規模較小的拉美裔和亞洲人群。這些數字并不能說明整個疫苗接種的格局,因為疾控中心掌握的種族數據僅占全美已接種人群的53%。然而,在這個賓州看似做得不甚理想的領域,整個美國也是不盡人意:在至少已經接種了一針疫苗的美國民眾中,8.2%是黑人,9.3%為拉美裔;然而黑人和拉美裔占美國總人口的比例分別為13.4%和18.5%。

費城44%的人口都是黑人,不公平現象也是司空見慣。總部位于賓州哈里斯堡的藥房連鎖Rite Aid是該市主要的疫苗配送商,其在線注冊系統理論上是面向所有居民開放。在3月底,市政府數據顯示,83%的Rite Aid疫苗接種者是白人,而且藥房接種白人與黑人的比例為11:1。問題在于:Rite Aid超過半數的疫苗流向了自駕前往市區的郊區居民,而這是符合賓州規定的。

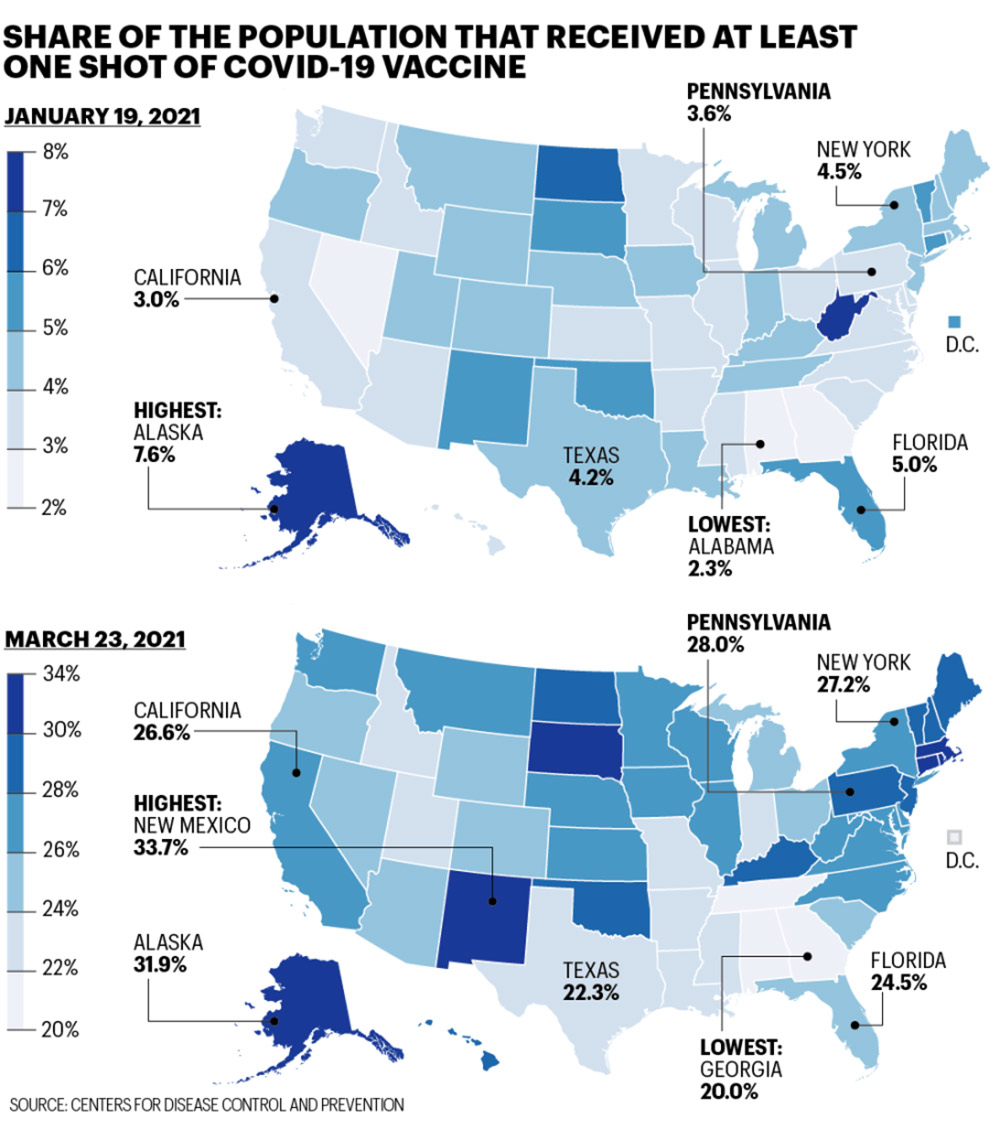

至少接種一針新冠疫苗的人口比例。來源:美國疾控中心

Rite Aid發言人稱,公司已經在過去一個月提升了流向賓州黑人居民的疫苗數量比重,而且將“盡其所能地解決引發接種不平等現象的眾多不一致問題。”一些因素確實已經超出了其控制范圍,例如郊區居民的侵入,這一點也部分解釋了為什么全美各大機構都無法解決疫苗注射的公平性。黑人和棕色人種群體更有可能是低收入人群,而且不大可能有機會接觸到能夠將其納入接種序列的醫療服務提供商。他們從事“必要性”、非遠程工作的可能性更大。所有這些因素為這些人通過系統進行接種預約設置了障礙,但這個系統卻為可以訪問互聯網的人,為能夠居家工作的人,為那些在一天之內有自由時間數次刷新預約網站的人提供了特權。

創建了費城“黑人醫生新冠疫情聯盟”的兒科外科醫生阿拉·斯坦福德說,為了克服這些不一致性,“光說‘我把一個鏈接放在了郡網站上’是不夠的,因為人們基本上看不到這個鏈接。”自1月以來,她的非盈利機構已經接種了3萬多名費城民眾;超過80%的接種人群是有色人種。該聯盟的上門服務診所僅面向特定郵編地區的居民提供接種服務(通常受新冠疫情影響最嚴重的地區)。斯坦福德說:“所有人都承認存在醫療服務不一致的問題,而且所有人都在談論這個話題,但沒有人積極制定解決方案。”

賓州衛生部長畢姆說:“我完全同意,我們需要下大力氣營造公平氛圍。”為了實現這一目標,賓州開始將其8%的聯邦疫苗分配額分發給非盈利性機構,像斯坦福德這樣的群體,以及“致力于接觸那些難以接觸人群的機構”。畢姆還表示,她希望“這一比例將不斷增長”。

種族不平等僅是賓州需要解決的問題之一。65歲以上人群的疫苗接種工作依然是一個挑戰。不過,賓州在這一方面的數字在3月底有所改善。畢姆和沃爾夫花費了數周的時間與地方政府機構爭論,如何向費城郊區發放更多的疫苗。

與此同時,賓州的個人、社區機構和私人實體應盡其所能減少民眾的困惑,并讓人們接種上疫苗。到3月底,克里斯汀·梅耶的Facebook團隊協助人們預約了超過1.3萬次的疫苗接種服務,而且梅耶甚至在考慮這個論壇在什么時候將完成其使命。

她說,賓州的疫苗接種“并不順暢,這并非易事,而且在很多方面都處于尷尬境地。”不過,她還表示:“我覺得現在更有希望了,因為我看到人們紛紛接種上了疫苗。”(財富中文網)

本文另一個版本登載于《財富》4月/5月刊,標題為《無疫苗可用:坎坷的賓州疫苗接種進程》。

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

在二月的一個下雪天,克里斯汀·梅耶突然意識到自己必須親自負責賓州的疫苗接種工作。

內科醫學醫師梅耶在賓州費城郊區的艾克斯頓擁有一家20000病患的醫院。數周以來,他一直在接聽病患的電話,這些病患擁有注射新冠疫苗的資質,但無法在藥房、醫生辦公室,或通過當地衛生部門以及州疫苗信息網站進行預約。大多數病患的歲數都超過了75歲,而且很多人難以通過各大系統在線進行注冊,因為這些系統對于科技設備操作的熟練度有很高的要求。

當暴風雪來臨時,梅耶取消了個人就診預約,并要求其醫師和員工在日間幫助病患注冊疫苗接種。她在其醫院的Facebook頁面上發布了貼文,在兩個小時內,有1200人向她的辦公室發送郵件尋求幫助,醫院服務器也因此而癱瘓。不久之后,梅耶在Facebook上創建了一個由志愿者經營的匹配服務,以便讓高齡人士或其孩子或鄰居,獲取找尋接種服務的幫助。截至3月底,這個組織的成員超過了6萬人(包括在賓州長大、身為記者且嘗試幫助其當地父母接種疫苗的我本人)。當時,很少有用戶在等待州發布的消息:論壇上討論的內容全是沃爾格林(Walgreens)、CVS、Rite Aid和其他藥房什么時候才會批量公布接種預約機會,以及如何最為高效地使用其通常令人抓狂的預約網站。

梅耶通過視頻向《財富》雜志透露:“說真的,疫苗接種事務讓我感到心力交瘁。”她的語速和手勢逐漸加快,并透露出一種沮喪情緒。“我把所有的希望和所有病患的希望都寄托在了衛生部門的身上,因為事情本該如此,然而這個流程出了問題。”

梅耶和數百萬賓州民眾意識到,賓州的疫苗接種問題遠非令人困惑的注冊流程那么簡單。擁有超過2.48萬家醫院的賓州是全美新冠疫情死亡人數排名第五的州,同時也是美國疫苗接種問題最嚴重的州之一。《貝克爾醫院評論對疾控中心數據的分析顯示,在1月底,賓州收到了近200萬劑疫苗,但僅接種了42%,在美國排名第49位,僅位于阿拉巴馬之前。該州240萬老年易感人群一直在想方設法獲取疫苗接種服務,然而,該州卻向兒科醫院發送了1.2萬劑疫苗,但大多數兒童都不宜接種。衛生部門隨后發出警告,因與提供商的溝通有誤,有10多萬民眾可能不得不重新調整其接種第二針Moderna疫苗的日期。

與此同時,《費城詢問報》的一項分析發現,相對于該州一些罕有人居住的農村地區,公共衛生機構向費城郊區——也就是梅耶的醫院所在地250萬居民——發放的人均疫苗數量少得多。一位州發言人對分析的方法表示質疑,但地方官員對發現結果表示贊同:在擁有56.5萬人的特拉華郡,郡議會副主席莫妮卡·泰勒說,曾幾何時,該郡“每周僅獲得1000劑疫苗,聽起來更像是電影《饑餓游戲》。”

賓州疫苗接種問題反映了眾多其他大型種族和社會經濟形態多樣化的州在應對這個超大型復雜流程時所遇到的困境。這個全國性的舉措要求在各個不對等的團隊之間開展前所未有的協調工作,這些團隊包括在這個充滿諷刺意味的總統過渡過程中耗費了數月時間的聯邦政府、資金窘迫的州和當地政府,以及由大型醫療服務提供商、小型診所以及美國財富500強藥房和百貨連鎖店拼湊起來的網絡,它們都在疲于應對不斷變化——通常是相沖突的分配和資質法規。

然而,賓州的疫苗接種問題尤為突出,其中一些是自身的問題。與其他州不一樣的是,賓州拒絕創建一個集中化的疫苗接種系統,而是讓居民個人來承擔疫苗接種預約這個異常復雜的難題。州與地方領導人之間存在的各種官僚主義、配送問題以及沖突進一步放慢了疫苗接種進程,將各自為政的風險暴露無遺。截至3月底,賓州疫苗接種的多個指標均有所改善。然而,該州未能有效地照顧到那些最為脆弱的人群,包括黑人和拉美裔居民。

反復出現的問題讓醫生、地方官員和公共衛生專家對繁瑣的手續以及協調的缺乏感到失望。匹茲堡黑人平等聯盟成員、匹茲堡大學醫學中心 McKeesport醫療系統家庭醫學項目主任特雷西·康提說:“事實在于,賓州沒有一個集中化的流程,這意味著人們只能依靠各個組織自行其是,并寄希望于這種模式能夠奏效。它帶來了諸多的不確定因素,而且讓人沮喪不已。”

賓州官員也承認存在上述問題。衛生局局長阿里森·畢姆向《財富》透露,賓州經歷了“死亡審判月。我們還有很多要改善的地方,但我們唯一希望的就是繼續前行。”

賓州最引人注目的疫苗丑聞超出了該州的管轄范圍,但它依然充斥著整個疫苗接種過程。1月,從聯邦政府直接獲得疫苗供應的費城讓一家未經證實的初創企業Philly Fighting COVID來經營其首個大規模疫苗接種診所。該公司創始人安德烈·多羅辛是德雷塞爾大學22歲的神經科學畢業生,他在疫情初期成為了當地的創業英雄,當時,他與朋友一道用3D打印技術為當地醫院打印面罩。隨后,他的初創企業(一開始是一家非營利性機構)贏得了費城衛生部門19.4萬美元的合約,在服務低下的城市周邊經營新冠病毒測試站點。

然而,公共媒體機構WHYY開展的一項調查稱,當費城要求該公司接手城市的疫苗接種服務診所時,這家公司突然拋棄了其位于黑人和拉美裔聚居地的測試站點。WHYY還報道稱,這家初創企業在沒有通知該市官員的情況下,注冊了一家盈利公司。為了完成其從英雄到惡棍的公開轉型,多羅辛被人發現(后自己承認)將疫苗帶回家供朋友注射。當時,有資質的費城民眾卻被拒之其診所門外。(多羅辛通過一名發言人表示,拒絕對此置評。該發言人還稱,“我們沒有同時開展測試和疫苗接種服務的資源”,但“事后我們認為停止測試是一個錯誤”。)

賓州大學護理學院副教授阿里森·布特海姆(新冠疫情科學專家聯合組織Dear Pandemic的聯合創始人)說:“我希望看到地方、郡和州層面的政府都能正確行事。在另一個宇宙,Philly Fighting COVID本應成為費城的一道最靚麗風景線。”

費城的檢察長亞歷山大·德桑提斯在3月發表的一篇報道稱,然而在當前的宇宙,費城的計劃“為城市帶來了很大的風險。”(該市衛生部門的一位發言人拒絕置評。)

依然在調查這個問題的德桑提斯說:“我們的政府倉促行事,試圖迅速對這個問題做出響應。這是個有問題的流程。”

這樁丑聞是賓州早期的丑事,它凸顯了一個在全美普遍存在的問題:政府缺乏有經驗的疫苗接種合作方。這項業務明顯應該是醫院和大型醫療機構提供商的工作,但這些機構自身也存在不少問題。疫情加劇了其中期預算和人手短缺問題。總的來看,大型醫療系統去年每天的損失高達近10億美元。費城一家頂級醫院的高級醫師稱:“前往社區注射疫苗的成本非常昂貴,這個過程需要大量的物流,同時還需要空間和招聘人手,而且醫療系統還不一定能賺到錢。”

由聯邦資助的社區醫療中心可能最適合給少數族裔和服務低下的人群接種疫苗,但這些群體稱,擴張這一服務的前提就是政府給他們分配更多的疫苗。

填補這一空白的是那些大型零售連鎖藥店,它們在此前每年令人不安的流感疫苗接種過程中積累了大量的經驗。巴克萊銀行(Barclays)稱,僅沃爾格林和CVS預計今年就會接種全美約25%的新冠疫苗。這些連鎖店在交付疫苗方面還擁有更加強勁的經濟動力。它們預計疫苗接種本身將帶來營收增長:這些收入來自于政府或保險公司支付的每次注射費用;來自于向進店注射的客戶推銷更多的物品;來自于因營銷目的而收集的客戶數據。這些連鎖店還稱,農村和種族多元化人群更容易接觸到這些連鎖店。CVS Caremark首席醫療官斯瑞·查古圖魯稱,85%的美國民眾居住在CVS藥房10英里范圍之內,而且稱該公司在“店面位置的選擇方面曾進行過一番深思熟慮”,尤其在決定每個州的哪些藥房能夠獲得疫苗供應時十分注重平等性。

在賓州,協調這些合作伙伴的速度尤其緩慢,部分原因在于領導的更換。1月19日,拜登總統任命賓州衛生部部長蕾切爾·萊文擔任美國衛生部助理部長。這一任命是歷史性的:兒科醫生萊文隨后成為了美國參議院首位公開身份的跨性別官員。然而,此舉卻讓萊文的家鄉州賓州感到越發困惑。

州長湯姆·沃爾夫任命其時任副幕僚長阿里森·畢姆擔任賓州衛生部代理部長。畢姆曾一直參與制定該州的疫苗策略,但她向《財富》透露,自己在應對疫苗供不應求的局面時已經習慣了“缺乏必要規劃”的做法,以及隨之而來的疫苗分配“缺乏控制”的現象。(萊文的知情人士稱,這位性格外向的部長“采取了一切可行的辦法來制定一個強有力的疫苗接種計劃”,但“毫無疑問的是,初期階段過后還需要對其進行改進。”)

沃爾夫和畢姆已經創建了一個兩黨立法工作組,得到了一些地方提供商的贊許,他們認為此舉提升了疫苗接種的溝通頻率和信息清晰度。賓州社區醫療中心協會政策與合作伙伴關系主任埃瑞克·吉爾說:“溝通頻率在過去4-5周中增加了10倍。”賓州社區醫療中心的成員致力于為近100萬得不到足夠服務的居民提供醫療服務。然而,“此舉并未改變這個大問題。每個人都在詢問和索要疫苗,但我們手頭就是沒有疫苗。”

2月,該州還與波士頓咨詢集團(Boston Consulting Group)簽署了一項價值1160萬美元的合約,幫助改善其疫苗分發服務。該集團曾幫助賓州精簡了畢姆所稱的“笨重的提供商網絡”,該網絡由獲得疫苗配送的醫生和藥房構成。同時,波士頓咨詢集團還升級了畢姆口中“異常神秘”的數據報告流程,并幫助畢姆解決了“需求大潮”問題,因為當時賓州曾發出警告,有10萬居民可能無法及時獲得其Moderna疫苗的第二針注射。(賓州援引了疾控中心的指引,要求接受第二針疫苗注射的居民等待高達42天,而不是通常的28天。)

畢姆說:“我們一直在搭建最根本的基礎設施,同時還得應對這些緊急情況。”如今,“我們讓形勢變得更加緊迫。”

自初期的失利之后,賓州也取得了一些進步。截至3月25日,賓州在全美大眾疫苗分發領域已經躋身前25之列。疾控中心稱,超過81%的供應得到了注射,超過了全美78%的平均水平,其中28%的州居民已經獲得了至少一針疫苗注射。3月31日,畢姆宣布,費城之外的所有成人在4月19日之后都可以注射疫苗(不過,城市中的居民可能得等到5月1號之后)。

然而此次疫苗接種工作在一些社區做得并不夠深入,尤其是有色人種社區,而這些人群受疫情的影響尤為嚴重。美國疾控中心稱,截至3月中旬,向費城以外地區提供的賓州疫苗僅有3%流向了黑人居民,而黑人卻占到了該州非賓州當地人人口的7.5%。類似的不一致性也影響了規模較小的拉美裔和亞洲人群。這些數字并不能說明整個疫苗接種的格局,因為疾控中心掌握的種族數據僅占全美已接種人群的53%。然而,在這個賓州看似做得不甚理想的領域,整個美國也是不盡人意:在至少已經接種了一針疫苗的美國民眾中,8.2%是黑人,9.3%為拉美裔;然而黑人和拉美裔占美國總人口的比例分別為13.4%和18.5%。

費城44%的人口都是黑人,不公平現象也是司空見慣。總部位于賓州哈里斯堡的藥房連鎖Rite Aid是該市主要的疫苗配送商,其在線注冊系統理論上是面向所有居民開放。在3月底,市政府數據顯示,83%的Rite Aid疫苗接種者是白人,而且藥房接種白人與黑人的比例為11:1。問題在于:Rite Aid超過半數的疫苗流向了自駕前往市區的郊區居民,而這是符合賓州規定的。

Rite Aid發言人稱,公司已經在過去一個月提升了流向賓州黑人居民的疫苗數量比重,而且將“盡其所能地解決引發接種不平等現象的眾多不一致問題。”一些因素確實已經超出了其控制范圍,例如郊區居民的侵入,這一點也部分解釋了為什么全美各大機構都無法解決疫苗注射的公平性。黑人和棕色人種群體更有可能是低收入人群,而且不大可能有機會接觸到能夠將其納入接種序列的醫療服務提供商。他們從事“必要性”、非遠程工作的可能性更大。所有這些因素為這些人通過系統進行接種預約設置了障礙,但這個系統卻為可以訪問互聯網的人,為能夠居家工作的人,為那些在一天之內有自由時間數次刷新預約網站的人提供了特權。

創建了費城“黑人醫生新冠疫情聯盟”的兒科外科醫生阿拉·斯坦福德說,為了克服這些不一致性,“光說‘我把一個鏈接放在了郡網站上’是不夠的,因為人們基本上看不到這個鏈接。”自1月以來,她的非盈利機構已經接種了3萬多名費城民眾;超過80%的接種人群是有色人種。該聯盟的上門服務診所僅面向特定郵編地區的居民提供接種服務(通常受新冠疫情影響最嚴重的地區)。斯坦福德說:“所有人都承認存在醫療服務不一致的問題,而且所有人都在談論這個話題,但沒有人積極制定解決方案。”

賓州衛生部長畢姆說:“我完全同意,我們需要下大力氣營造公平氛圍。”為了實現這一目標,賓州開始將其8%的聯邦疫苗分配額分發給非盈利性機構,像斯坦福德這樣的群體,以及“致力于接觸那些難以接觸人群的機構”。畢姆還表示,她希望“這一比例將不斷增長”。

種族不平等僅是賓州需要解決的問題之一。65歲以上人群的疫苗接種工作依然是一個挑戰。不過,賓州在這一方面的數字在3月底有所改善。畢姆和沃爾夫花費了數周的時間與地方政府機構爭論,如何向費城郊區發放更多的疫苗。

與此同時,賓州的個人、社區機構和私人實體應盡其所能減少民眾的困惑,并讓人們接種上疫苗。到3月底,克里斯汀·梅耶的Facebook團隊協助人們預約了超過1.3萬次的疫苗接種服務,而且梅耶甚至在考慮這個論壇在什么時候將完成其使命。

她說,賓州的疫苗接種“并不順暢,這并非易事,而且在很多方面都處于尷尬境地。”不過,她還表示:“我覺得現在更有希望了,因為我看到人們紛紛接種上了疫苗。”(財富中文網)

本文另一個版本登載于《財富》4月/5月刊,標題為《無疫苗可用:坎坷的賓州疫苗接種進程》。

譯者:馮豐

審校:夏林

It was a February snow day that made Christine Meyer snap—and realize she had to take Pennsylvania’s vaccine rollout into her own hands.

Meyer, an internal medicine physician who owns a 20,000-patient practice in Exton, Pa., in the Philadelphia suburbs, had spent weeks fielding calls from patients who were eligible for COVID-19 vaccines but who couldn’t find an appointment—at pharmacies, at doctors’ offices, via local health departments, or through the state’s vaccine-information website. Most of them were over 75, and many struggled to register online through systems that required tech savvy.

When a snowstorm hit, canceling in-person appointments, Meyer asked her clinicians and staff to spend the day helping patients register for jabs. She posted about it on her practice’s Facebook page—and within two hours she had 1,200 people emailing her office for help, crashing her servers. Soon Meyer created a volunteer-run matchmaking service on Facebook, allowing seniors—or their children or neighbors—to request help finding a vaccine. As of late March, the group had more than 60,000 members (including this Pennsylvania-raised reporter, trying to help her local parents). By then, few users were waiting to hear from the state: The forum was dominated by talk about when Walgreens, CVS, Rite Aid, and other pharmacies were releasing blocks of appointments, and how best to navigate their often-maddening websites.

“This vaccine thing honestly bowled me over,” Meyer told Fortune via video, her voice and hand gestures speeding up with frustration. “I put all of my faith, and all of my patients’ faith, in the health department—because that’s how it was supposed to work. But the process is broken.”

As Meyer and millions of Pennsylvanians have learned, the state’s vaccine-rollout problems run far deeper than a confusing sign-up process. The Keystone State, with more than 24,800 fatalities, is the state with the fifth-highest COVID-19 death toll. It also has one of the nation’s longest litanies of vaccine stumbles. At the end of January, Pennsylvania had received nearly 2 million doses but had distributed only 42%—ranking the state 49th, ahead of onlyAlabama, according to a Becker’s Hospital Review analysis of CDC data. As the state’s 2.4 million seniors scrambled to find vaccines for a disease they are particularly vulnerable to, the state sent 12,000 doses to pediatric offices—even though most children aren’t yet eligible for shots. The health department later warned that more than 100,000 people might have to reschedule their second appointments for the two-dose Moderna vaccine because of miscommunication with providers.

Meanwhile, public health authorities were sending far fewer doses per capita to the 2.5 million residents of the Philadelphia suburbs—Meyer’s territory—than to some of the state’s sparsely populated rural enclaves, a Philadelphia Inquirer analysis found. A state spokesperson disputes the analysis’s methods, but local officials echo its findings: At one point, says Monica Taylor, council vice chairperson of 565,000-person Delaware County, the county was “getting only 1,000 doses a week. It made it more like the Hunger Games.”

Pennsylvania’s rollout problems have mirrored those of many other large, racially and socioeconomically diverse states as they navigate a massively complex process. The national effort has required unprecedented coordination among a mismatched team of players, including a federal government that squandered months in an acrimonious presidential transition; cash-strapped state and local governments; and a patchwork of big health care providers, small clinics, and Fortune 500 pharmacy and grocery chains sorting through changing—and often conflicting—distribution and eligibility rules.

Still, Pennsylvania’s campaign has stood out for its problems, some of which are self-inflicted. Unlike some of its peers, Pennsylvania declined to create a centralized vaccination system, putting the burden on individual residents to navigate the appointment maze. A host of bureaucratic complications, distribution failures, and conflicts between state and local leaders have slowed things down even more—showing the danger of an every-party-for-itself approach. By late March, Pennsylvania had improved its rollout by several metrics. But it continues to struggle to reach its most vulnerable populations, including Black and Latinx residents.

The persistent problems have left doctors, local officials, and public health experts lamenting an excess of red tape and a lack of coordination. “The fact that there’s not a centralized process across the state means that you’re really depending on each individual organization doing their own thing and hoping that it works,” says Tracey Conti, a member of the Pittsburgh-based Black Equity Coalition and program director of family medicine at the UPMC McKeesport health care system. “It creates a lot of unknowns—and a lot of frustration.”

State officials acknowledge as much. Pennsylvania has gone through “a month of reckoning,” acting Health Secretary Alison Beam tells Fortune. “There is a lot of room to improve—and we only want to be moving forward.”

Pennsylvania’s most headline-grabbing vaccine scandal wasn’t within the state’s control—but it continues to resonate across its rollout. In January, the city of Philadelphia, which gets its vaccine supply directly from the federal government, asked an unproven startup called Philly Fighting COVID to run its first mass vaccination clinic. Founder Andrei Doroshin, a 22-year-old neuroscience grad student at Drexel University, had become a local entrepreneurial hero in the early days of the pandemic, recruiting friends to 3-D print face shields for local hospitals. Then his startup, which initially operated as a nonprofit, won a $194,000 contract from Philadelphia’s health department to operate COVID-19 testing sites in underserved city neighborhoods.

But once it was asked to run the city’s vaccination clinic, Philly Fighting COVID abruptly abandoned its testing commitments in predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods, according to an investigation by public-media organization WHYY—which also reported that the startup had, without informing city officials, registered a for-profit arm. To complete his public transformation from hero to villain, Doroshin was seen—and later admitted to—taking home vaccine doses for his friends, on a day when eligible Philadelphians were shut out at his clinic. (Doroshin declined to comment through a spokesperson, who said that “we didn’t have the resources to do testing and vaccinations at the same time,” but “it was a mistake in hindsight” to stop testing.)

“I love reading about governments—on a local, county, and state level—that are getting it right. And in an alternate universe, Philly Fighting COVID could have been the best thing that happened to Philadelphia,” says Alison Buttenheim, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (and a co-founder of the “Dear Pandemic” collective of COVID-19 scientific experts).

But in this universe, Philadelphia’s plan “placed the city at great risk,” a March report from city Inspector General Alexander DeSantis found. (A spokesperson for the city health department declined to comment.)

“Our government was working in a hurry and trying to respond to something really quickly,” says DeSantis, who is continuing to investigate the affair. “It was a process that broke.”

The scandal was an early black eye for Pennsylvania, and it highlighted a common problem nationwide—the lack of established vaccine partners for governments. Hospitals and large health care providers might seem like obvious distributors, but they face problems of their own. The pandemic exacerbated their enduring budget and personnel crunches; collectively, large health care systems were estimated to be losing almost $1 billion a day last year. “It’s expensive to go out there in the community and put shots in arms,” says a senior physician at a top Philadelphia hospital. “It requires a lot of logistics, space, and hiring people—and it’s not necessarily going to make a health system money.”

Federally funded community health centers may be best positioned to vaccinate minority and underserved populations, but those groups say they need bigger allocations of vaccines from governments to scale up.

Into this vacuum have stepped the large retail pharmacy chains—already experienced at distributing yearly flu shots. Walgreens and CVS alone are expected to give out about 25% of COVID shots nationwide this year, according to Barclays. Those chains also have stronger economic incentives around delivering vaccines. They expect revenue growth from the rollout itself—from government or insurance payments per shot; from selling more stuff to customers who come in for shots; and from collecting customers’ data for marketing purposes. The chains also claim to be more accessible to rural and racially diverse populations. CVS Caremark chief medical officer Sree Chaguturu notes that 85% of Americans live within 10 miles of a CVS pharmacy, and says that the company has tried to “be really thoughtful on store locations,” especially in terms of equity, when making decisions about which pharmacies in each state get its supply of vaccines.

In Pennsylvania, coordination among these partners was especially slow to jell—owing in part to a change in command. On Jan. 19, President Biden appointed Rachel Levine, the state secretary of health, to be U.S. assistant secretary of health. The nomination was historic: Levine, a pediatrician, later became the first openly transgender official confirmed by the U.S. Senate. But it only added to the confusion in her home state.

Gov. Tom Wolf appointed his then deputy chief of staff, Alison Beam, as acting secretary of health. Beam had been involved in the state’s vaccine strategy, but she tells Fortune that she inherited “a lack of the necessary planning” for dealing with demand that outpaced supply, and a resulting “lack of controls” in how to allocate vaccines. (A source close to Levine says that the outgoing secretary “did everything feasible to put together a robust vaccine plan” but that “there’s no question improvements needed to be made after the initial phase.”)

Wolf and Beam have created a bipartisan legislative task force, which some local providers praise for increasing the frequency and clarity of information around the rollout. “The communication has increased tenfold over the past four to five weeks,” says Eric Kiehl, director of policy and partnership at the Pennsylvania Association of Community Health Centers, whose members provide health care to nearly 1 million underserved residents. But “that doesn't change the big issue. Everybody’s calling and wanting vaccine, and we just don’t have it.”

In February, the state also gave Boston Consulting Group an $11.6 million contract to help improve its vaccine distribution. BCG has helped Pennsylvania pare down what Beam calls “an unwieldy provider network” of doctors and pharmacies who have been allocated vaccines, and it’s upgrading what Beam says is the state’s “undoubtedly arcane” data-reporting process. It also helped Beam work through a “tidal wave” of requests when the state warned that up to 100,000 residents might not get their second Moderna shots in time. (Citing CDC guidance, Pennsylvania addressed the shortage by asking residents to wait up to 42 days for their second shots, instead of the more usual 28.)

“We were working on the foundational infrastructure” and “simultaneously responding to these fires,” Beam says. Now, “we are driving the urgency.”

Since those early days, Pennsylvania has made up some ground. As of March 25, the state had climbed into the top half of states for vaccine distribution among the general population. More than 81% of its supply has been administered, according to the CDC, surpassing the national average of 78%, and 28% of state residents had received at least one dose. And on March 31, Beam announced that all adults outside of Philadelphia would be eligible for a vaccine by April 19 (although those in the city may have to wait until May 1).

But the rollout hasn’t penetrated far enough into some communities—especially communities of color, which have been disproportionately harmed by the pandemic. By mid-March only 3% of Pennsylvania’s vaccines outside Philadelphia had gone to Black residents, according to the CDC, even though Black people account for 7.5% of the state’s non-Philly population; similar disparities affect the smaller Latinx and Asian populations. These numbers don’t paint a complete picture, since the CDC has racial data available for only 53% of national vaccine recipients. Still, Pennsylvania seems to be underdelivering on a front where the nation already does poorly: Of Americans who have had at least one dose, 8.2% are Black and 9.3% are Latinx; while the U.S. population as a whole is 13.4% Black and 18.5% Latinx.

In Philadelphia, whose population is 44% Black, the inequities are just as stark. Rite Aid, the pharmacy chain based in Harrisburg, Pa., is one of the city’s dominant distributors, with an online registration system that’s theoretically equally open to all residents. In late March city government data showed that 83% of Rite Aid’s vaccine recipients were white, and that the pharmacy had inoculated nearly 11 white people for every Black person who received a shot. One problem: More than half of Rite Aid shots went to suburban residents who drove into the city—which is permissible under state guidelines.

A Rite Aid spokesperson says the company has increased the share of vaccine doses going to Black Pennsylvanians within the past month, and is “working tirelessly to overcome the many disparities” that cause vaccine inequity. Some factors are indeed outside its control, like the suburbanite invasion—which also illuminates some of the reasons why authorities nationwide are flunking vaccine equity. Black and brown people are more likely to be lower-income and less likely to have access to health care providers who can steer them into the vaccination pipeline. They’re also more likely to work in “essential,” non-remote jobs. All those factors create barriers to getting vaccine appointments through systems that privilege people with Internet access, the ability to work from home, and the free time to refresh scheduling websites multiple times a day.

To overcome these disparities, “it’s not enough to say, ‘I put a link out on a county website,’ where it was in essence buried,” says Ala Stanford, the pediatric surgeon who founded Philadelphia’s Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium. Since January, her nonprofit has vaccinated more than 30,000 Philadelphians; more than 80% of the recipients are people of color. The organization runs walk-up clinics that administer shots only to residents of specific zip codes (usually those hardest-hit by COVID). “Everyone acknowledges the health disparities. And everybody talks about it—but no one makes an active plan,” Stanford says.

“I absolutely agree that we need to make inroads on equity,” says Beam, the health secretary. To do so, the state has started dedicating 8% of its federal vaccine allocations to nonprofits, groups like Stanford’s and “entities that show that they are reaching hard-to-reach populations,” Beam says, adding that she hopes “that share will be ever-increasing.”

50%+

SHARE OF VACCINES FROM PHILADELPHIA RITE AID PHARMACIES THAT HAVE BEEN DISTRIBUTED TO PEOPLE WHO LIVE OUTSIDE THE CITY. SOURCE: RITE AID

50%+

Racial equity is only one of the puzzles the state needs to solve. Access has also been a challenge for those 65 and older, although Pennsylvania’s numbers there had improved by the end of March. And Beam and Wolf have spent weeks embroiled in arguments with local authorities over how to increase distribution of vaccines to the Philadelphia suburbs.

In the meantime, individuals, community organizations, and private entities all over the state do what they can to cut through the confusion and get jabs in arms. By late March, Christine Meyer’s Facebook group had facilitated more than 13,000 vaccine appointments—and Meyer was even contemplating the day when the forum might no longer be needed.

Pennsylvania’s rollout is “not smooth, it’s not easy, it’s embarrassing in a lot of ways,” she says. Still, she adds, “I feel more hopeful—because I see people getting vaccines.”

A version of this article appears in the April/May issue of Fortune with the headline, "Missing their shot: A rocky rollout in Pennsylvania."