作為美國第三大銀行的CEO,查爾斯·沙夫?qū)Ω粐y行的潛力是抱有很大期望的。

他對這家銀行的優(yōu)勢如數(shù)家珍。首先,這是一家服務(wù)數(shù)百萬小企業(yè)的商業(yè)銀行;其次,它的消費(fèi)信貸平臺發(fā)放的抵押貸款,超過了全美各大銀行;另外,它的財(cái)富管理部門幫助不計(jì)其數(shù)的客戶擴(kuò)大了財(cái)富。

“它的核心競爭力,以及我們?yōu)橄M(fèi)者和企業(yè)所做的一切,都是非同一般的。”

他停頓了幾秒,實(shí)事求是地補(bǔ)充道:“但我們也犯了不少錯(cuò)誤。”

這一天是十月中旬,再過一天,沙夫執(zhí)掌富國銀行就滿一周年了。他坐在紐約長島家中一間木質(zhì)裝修的書房里,通過視頻會議軟件Zoom接受了我們的采訪。

由于疫情關(guān)系,這一年的大部分時(shí)間里,沙夫都是在這里發(fā)號施令,試圖完成扭轉(zhuǎn)富國銀行頹勢的任務(wù)。

富國銀行在美國金融界是個(gè)龐然大物,涉及多個(gè)業(yè)務(wù)領(lǐng)域,擁有26萬余名員工和大約7000萬名客戶。眼下正是富國銀行近170年歷史中最動蕩的時(shí)期,因?yàn)樽罱啻伪蝗恕白グ睘E用客戶的信任。

直到現(xiàn)在,富國銀行仍在為這些錯(cuò)誤付出代價(jià),不僅公司名聲受到了損失,還要承擔(dān)巨額罰款和嚴(yán)厲的政策制裁。其中最沉重的一擊,是美聯(lián)儲給它戴上了一頂1.95萬億美元的“資金帽”,即該銀行的資本不得超過上述上限。

受疫情影響,美國所有銀行都在超低利率中瑟瑟發(fā)抖,其他銀行還通過可以大量增加放貸和吸收資本儲備來“過冬”,但美聯(lián)儲給富國銀行的“緊箍咒”卻直接斷絕了它的這種可能性。

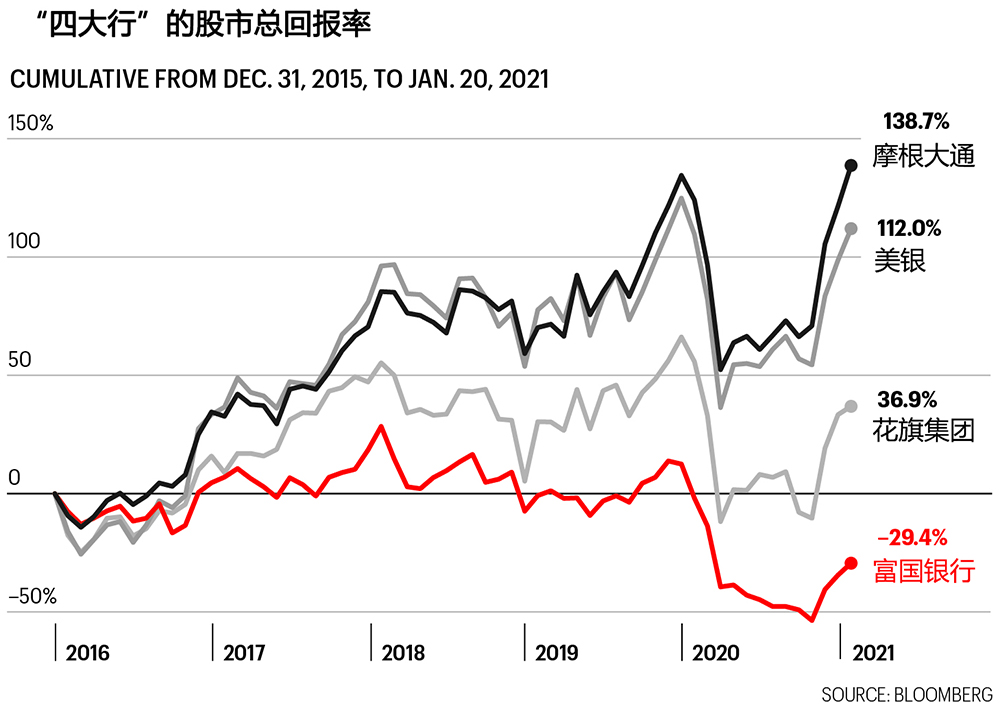

自2017年起,富國銀行的收入一直在穩(wěn)步下跌,在2020財(cái)年又下降了15%,只有723億美元,利潤也同步縮水了。而且自從爆出丑聞以來,它的股市表現(xiàn)一直不如其他大銀行。去年更是暴跌44%。

加拿大皇家銀行資本市場公司的美國銀行業(yè)證券策略主管杰拉德?卡西迪指出:“這家公司已經(jīng)千創(chuàng)百孔了,所有策略都必須拿到桌面上,好讓它恢復(fù)到一個(gè)投資者可以接受的盈利水平。”

當(dāng)現(xiàn)年55歲的沙夫接手時(shí),這份工作直接將他推上了金融業(yè)的風(fēng)口浪尖。

這已經(jīng)是他第三次擔(dān)任“財(cái)富500強(qiáng)”金融服務(wù)企業(yè)的CEO了,而且這份工作的報(bào)酬也是相當(dāng)豐厚的。根據(jù)富國銀行的股票激勵(lì)政策,他每年有可能能賺到2300萬美元。但富國銀行的CEO,也是全美國最難干的CEO。富國銀行是美國最大的借貸機(jī)構(gòu)之一,它感冒了,美國的宏觀經(jīng)濟(jì)都要打噴嚏。

沙夫一直以來的導(dǎo)師——摩根大通CEO杰米?戴蒙對《財(cái)富》表示,沙夫承擔(dān)的任務(wù)“事關(guān)重大”,并表示“如果他們成功了,對全國乃至整個(gè)銀行業(yè)都有好處。”

目前,沙夫正專心致志地在精簡機(jī)構(gòu)上下工夫——為了救命,只得先“縮水”、“瘦身”。

如果他成功了,他或許能將富國銀行從監(jiān)管的“緊箍咒”下解放出來,重現(xiàn)昔日榮光。如果他失敗了,面對一眾藍(lán)籌股競爭對手的后來居上,富國銀行可能將永遠(yuǎn)無法再現(xiàn)輝煌了。

在沙夫擔(dān)任CEO大約15個(gè)月后,為了了解富國銀行的改革情況,《財(cái)富》采訪了沙夫和富國銀行的高管,以及一些分析師、批評人士、行業(yè)競爭對手,還有沙夫以前的同事。

由于正逢多事之秋,富國又迎來了大規(guī)模的組織變革,加上一些重大失誤,人們不禁懷疑,沙夫是否有能力推動一次徹底的企業(yè)文化變革。

巴克萊銀行的高級證券研究分析師賈森?戈德堡表示: “讓這么大的一艘船掉頭需要很長時(shí)間,他正在學(xué)習(xí)。”

沙夫認(rèn)為,富國銀行還是有機(jī)會恢復(fù)原來的地位的。他表示:“我來的時(shí)候就很清楚,富國仍然有很好的發(fā)展機(jī)會,不過我們還有大量的工作要做。”

沙夫是在新澤西州的威斯菲德長大的,那里是紐約市的郊區(qū)。他父親是一名股票經(jīng)紀(jì)人,身邊也都是金融專業(yè)人士。從13歲時(shí)開始,沙夫已經(jīng)在曼哈頓的股票交易所里做一些后臺工作了。

在約翰霍普金斯大學(xué)讀本科時(shí),他最初的目標(biāo)是從事化學(xué)研究。不過讀大二的時(shí)候,他突然頓悟了:“當(dāng)時(shí)我在上物理化學(xué)課,我被關(guān)在一間實(shí)驗(yàn)室里,然后我對自己說:‘我不想一輩子待在一個(gè)連窗戶都沒有的地方。’”同時(shí)他意識到,在商業(yè)上,“你可以以一種完全不同的方式來創(chuàng)造事物。”

或許是命中注定,沙夫的一個(gè)親戚恰好認(rèn)識杰米?戴蒙的父親,當(dāng)時(shí)年輕的杰米·戴蒙還在巴爾的摩的商業(yè)信貸銀行里當(dāng)財(cái)務(wù)總監(jiān)。1987年,戴蒙將剛畢業(yè)的沙夫招入公司,他倆的工作關(guān)系就此持續(xù)了20多年。而這家商業(yè)信貸銀行就是花旗集團(tuán)的前身。

在杰米·戴蒙和桑迪?威爾領(lǐng)導(dǎo)下,沙夫在商業(yè)信貸銀行發(fā)展成為花旗集團(tuán)的過程中發(fā)揮了一系列作用。2000年,戴蒙擔(dān)任了美國第一銀行的首席執(zhí)行官,并任命沙夫?yàn)榈谝汇y行首席財(cái)務(wù)官。2004年,美國第一銀行與摩根大通合并后,沙夫又接手了摩根大通規(guī)模龐大的零售銀行業(yè)務(wù)。

戴蒙回憶道,沙夫能夠“處理我甩給他的任何任務(wù)”。

他說:“他能把事情做好,而且他的商業(yè)嗅覺也很靈敏。”隨著職務(wù)越來越高,沙發(fā)的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)才能也愈發(fā)出眾。

他還發(fā)現(xiàn),隨著戴蒙領(lǐng)導(dǎo)的公司規(guī)模越來越大,戴蒙的工作風(fēng)格也在發(fā)生變化。他說:“他總是挺身而出,而不是躲在別人后面。當(dāng)某件事出錯(cuò)時(shí),他總是親自處理。”

2012年,沙夫被Visa聘為首席執(zhí)行官,他的這些經(jīng)驗(yàn)終于有了用武之地。

當(dāng)時(shí),Visa還處于從一家發(fā)卡銀行協(xié)會所屬的私人企業(yè)向一家上市公司的艱難轉(zhuǎn)型中。到了Visa的舊金山總部后,沙夫發(fā)現(xiàn),這竟然還是一家“與世隔絕”的企業(yè),尚未“真正融入科技界”。

為了糾正這種情況,他與PayPal和Stripe等金融科技公司建立了合作關(guān)系,擴(kuò)展了Visa在數(shù)字支付領(lǐng)域的存在。事實(shí)證明,他的這一招是很有遠(yuǎn)見的。

現(xiàn)任Visa總裁瑞安?麥金納尼也是從摩根大通出來的,當(dāng)年跟著沙夫一起去了Visa。他表示:“當(dāng)時(shí)他做的很多基礎(chǔ)性工作,特別是跟電商有關(guān)的部分,現(xiàn)在我們都看到了成果。”

為了離東海岸的家人近一些,2016年,沙夫離開了Visa。在他任內(nèi),Visa的股價(jià)上漲了一倍多。

在Visa的經(jīng)歷,以及隨后在紐約梅隆銀行擔(dān)任CEO的經(jīng)歷,讓他明白了一個(gè)CEO的職責(zé)有多龐雜。沙夫感言:“沒有任何一個(gè)工作可以與之相比。整個(gè)企業(yè)的成敗都系于你一人,要指望你來定調(diào)子、培養(yǎng)企業(yè)文化……有些人喜歡這項(xiàng)工作,也有些人不喜歡。”而沙夫?qū)儆诘谝活悺?/p>

就在他離開Visa的時(shí)候,另一家總部位于舊金山的金融機(jī)構(gòu),卻爆出了一樁大丑聞。

關(guān)于富國銀行的虛假賬戶欺詐案,有很多細(xì)節(jié)都是有據(jù)可查的。

在極端扭曲的銷售文化驅(qū)動下,富國銀行員工未經(jīng)客戶同意,便為幾百萬個(gè)客戶開立了賬戶,并向他們銷售金融產(chǎn)品,這在當(dāng)時(shí)已經(jīng)成了整個(gè)公司的普遍現(xiàn)象。在房貸、車貸和財(cái)富管理業(yè)務(wù)上,也出現(xiàn)了類似的欺詐行為。

這種風(fēng)氣最終帶來了毀滅性的結(jié)果。

從2016年到2018年,聯(lián)邦監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)連發(fā)五道命令,曝光了富國銀行的管理亂象,同時(shí)對其施加了包括“資金帽”在內(nèi)的制裁。

監(jiān)管部門也沒有放過富國銀行高層的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)責(zé)任。2016年下臺的前任CEO約翰·斯坦普被處以1750萬美元罰款,并勒令其終身不得再從事銀行業(yè)。他的繼任者蒂姆·斯隆在2019年3月迫于政治壓力辭職。

美國眾議院金融服務(wù)委員會在去年一份報(bào)告中猛烈抨擊了富國銀行的董事會和管理層——丑聞都已經(jīng)曝光好幾年了,你們怎么還沒有解決公司的問題?

在欺詐丑聞之前,富國銀行算是少數(shù)幾家名聲還算不錯(cuò),而且全須全尾地挺過了2008年金融危機(jī)的美國銀行之一。一個(gè)個(gè)競爭對手都被金融危機(jī)打得灰頭土臉,富國銀行卻變得更加強(qiáng)大,還在金融危機(jī)期間以150億美元收購了美聯(lián)銀行。

但現(xiàn)在它已經(jīng)成了銀行業(yè)的眾矢之的。

在富國銀行奉獻(xiàn)了15年的老將瓊恩?威斯表示:“那時(shí)我們在忙增長,而其他銀行都專注于如何更好地經(jīng)營。在某種程度上,我們是自身成功的受害者,也許我們當(dāng)時(shí)就應(yīng)該多反省一下。”

2019年春天,富國銀行董事會開始尋找一位能夠真正發(fā)現(xiàn)問題并解決問題的CEO。在斯隆下臺6個(gè)月后,沙夫得到了這份工作。

他上任不久即表示,解決當(dāng)前面臨的監(jiān)管問題,“顯然是首要任務(wù)”。

在新CEO的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)下,富國銀行的運(yùn)營委員會召開了第一次會議,頭頭腦腦們聚集在圣路易斯的一間沒有窗戶的會議室里,討論如何扭轉(zhuǎn)當(dāng)前的不利局面。

威斯回憶道:“沙夫帶來了一個(gè)便箋本,而不是那種四五十頁圖文并茂的PPT,本子上做了大概一頁半的筆記,他一行一行地講解了他做生意的重點(diǎn),這是一次讓人放下戒備、較為隨意但又非常專注的討論,沒有任何廢話。”

實(shí)事求是和“不搞形式主義”,是很多人對沙夫的印象。他的直率就像他的滿頭白發(fā)一樣引人注目。但對一位需要經(jīng)常傳達(dá)壞消息并處理棘手事的CEO來說,坦率也是一筆重要的資產(chǎn)。

沙夫發(fā)現(xiàn),富國銀行最大的問題,是組織結(jié)構(gòu)異常松散,缺乏明確的權(quán)責(zé)界限,否則像賬戶欺詐這樣的現(xiàn)象是可以避免的。另外,富國銀行還缺乏大多數(shù)銀行已經(jīng)建立的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)和合規(guī)保障機(jī)制。

瑪麗?麥克已經(jīng)在富國銀行工作了26年,目前負(fù)責(zé)消費(fèi)者和小企業(yè)銀行業(yè)務(wù)。她表示:“當(dāng)時(shí),我們的內(nèi)部組織結(jié)構(gòu)確實(shí)較為封閉,各部門的業(yè)務(wù)較為獨(dú)立。其實(shí)我們應(yīng)該退一步審視一下,問問自己:‘那種情況,或者說那些弱點(diǎn),是不是真的在整個(gè)公司都存在?’但我們在這方面做得并不好。”

沙夫開始了大刀闊斧的改革,首先從高層人事變動開始。

目前沙夫的高管團(tuán)隊(duì)一共有17人,其中9人都是新聘用的。去年以前,富國銀行還沒有首席運(yùn)營官這個(gè)職位。沙夫設(shè)立了這個(gè)崗位,并且請來了他花旗集團(tuán)和摩根大通的老同事斯科特?鮑威爾來擔(dān)任首席運(yùn)營官。在此之前,鮑威爾曾擔(dān)任桑坦德銀行美國業(yè)務(wù)的CEO,任內(nèi)幫助桑坦德銀行妥善應(yīng)對了監(jiān)管部門的制裁。

其他幾位新人也多半是沙夫的老同事,CFO邁克?桑托馬西莫原本是紐約梅隆銀行的CFO;消費(fèi)貸款部門和財(cái)富管理部門的負(fù)責(zé)人邁克?魏巴赫和巴里?索莫斯,也都是沙夫在摩根大通的老相熟。

2020年2月,沙夫公布了一項(xiàng)重組計(jì)劃,將公司業(yè)務(wù)劃分為五個(gè)不同的部門。另外,他還重組了富國銀行的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)管理體系,這五個(gè)部門現(xiàn)在都有獨(dú)立的風(fēng)控官,通過這樣的制度設(shè)計(jì),來確保沒有任何一個(gè)部門敢搞小動作。

這樣一來,富國銀行在制度設(shè)計(jì)上吸取了其他銀行的最佳做法,使沙夫收獲了不少分析師的贊揚(yáng)。但后來發(fā)生的事表明,富國仍有大量工作要做。

去年2月,就在富國銀行的重組計(jì)劃公布的幾天后,美國司法部宣布,富國銀行將支付30億美元罰款,以達(dá)成丑聞相關(guān)指控的刑事調(diào)解。當(dāng)時(shí)人們普遍認(rèn)為,這將是富國銀行的最后一筆大額罰款,不過這也說明了丑聞對公司利潤的影響有多深。

另一件事也能說明丑聞給公司成本帶來了多大壓力:2020年,富國銀行在“專業(yè)服務(wù)/外部服務(wù)”上耗費(fèi)了67億美元,超過了年度總收入的9%。這筆費(fèi)用的大頭,無非是花在了官司善后的法務(wù)和咨詢費(fèi)上。

正所謂禍不單行,疫情一來,富國銀行只得將日常應(yīng)急工作放在長期改革前面。

沙夫連公司的人都沒完全認(rèn)熟,就只得坐困長島一隅,開始居家辦公。疫情期間,最重要的是讓幾千家分支機(jī)構(gòu)繼續(xù)開門營業(yè)。

即便是在封城期間,“每天也有100萬左右的顧客進(jìn)入我們的分支機(jī)構(gòu)。”瑪麗?麥克說。但要保證顧客的安全,并且讓非分支機(jī)構(gòu)的員工轉(zhuǎn)入遠(yuǎn)程辦公,這給公司的后勤工作提出了難題。

疫情期間,富國銀行又爆出了一個(gè)小丑聞,說明富國銀行的“整風(fēng)之路”依然任重道遠(yuǎn)。

去年,美國政府出臺了一些政策,以幫助那些因失去收入而無法償還抵押貸款的人。但有1600多名借款人投訴稱,富國銀行在沒有征得他們同意的情況下,給他們辦理了暫緩還款,而這種行為很有可能損害借款人的信用評級,影響他們的再次貸款能力。

在談到這次混亂時(shí),沙夫表示,富國已經(jīng)努力糾正了這個(gè)錯(cuò)誤。“在非常艱難的時(shí)期里,我們在試圖幫助客戶的時(shí)候犯了錯(cuò)。每個(gè)金融機(jī)構(gòu)都會犯錯(cuò)。”

富國銀行還被卷進(jìn)了人才多元化這種高度敏感的問題。

去年6月,他在一份備忘錄里,對銀行高層職位的人才儲備深度提出了質(zhì)疑。他在備忘錄中寫道:“不幸的現(xiàn)實(shí)是,有這種特殊經(jīng)驗(yàn)的黑人人才非常有限,”這也是一年來,對他個(gè)人聲譽(yù)威脅最嚴(yán)重的一件事了。

因?yàn)榫驮谏撤蜻M(jìn)行此番表述的幾周前,美國發(fā)生了黑人男子喬治·弗洛伊德被“跪殺”事件,結(jié)構(gòu)性的種族歧視成為全美上下高度關(guān)注的尖銳問題。沙夫的言論在此時(shí)顯得異常刺耳,不僅令許多員工感到不滿,也引發(fā)了外部人士的廣泛批評。

他們強(qiáng)調(diào),沙夫的很多左膀右臂都是他的老同事,而且是清一色的白人男性。雖然高管層里也有一名女性和兩名黑人男性,但都處于邊緣職位,而COO、CFO等關(guān)鍵崗位仍然是清一色的白人男性。

美國金融勞工組織改進(jìn)銀行委員會的尼克·韋納認(rèn)為:“我們看到的是,他用另一個(gè)孤立的團(tuán)體,取代了一個(gè)孤立的團(tuán)體。”

沙夫很快就為他的“黑人人才有限”言論道了歉,并表示,有關(guān)言論反映出“我自己無意識的偏見”。從那以后,富國銀行建立了一個(gè)專門負(fù)責(zé)多元化、代表性和包容性的部門。

其負(fù)責(zé)人克萊貝爾·桑托斯是去年11月剛從第一資本銀行跳槽來的,現(xiàn)在他也在高管委員會有了一席之地。幾個(gè)月后,沙夫?qū)@次“禍從口出”的事件開展了嚴(yán)肅的自我批評,并表示未來五年,要將公司高管隊(duì)伍中的黑人比例增加一倍,而且公司計(jì)劃將把部分高管的薪水與本部門員工隊(duì)伍的多元化程度掛鉤。

他似乎也敏銳地意識到,多年以來,他喜歡從外部請來神秘“強(qiáng)援”的做法,只會進(jìn)一步固化晉升渠道的不公。他表示:“看看這家公司的內(nèi)部代表性——而且大多數(shù)金融機(jī)構(gòu)都是這個(gè)樣子,你就會發(fā)現(xiàn),我們非常有必要采取不同的做法。”

乍一看,1月15日對富國銀行來說,只不過又是一個(gè)普通到沉悶的日子。

這一天,富國銀行2020年四季度的財(cái)報(bào),其營收低于分析師的預(yù)期,導(dǎo)致當(dāng)天股價(jià)下跌了近8%。然而由此帶來的沮喪情緒卻掩蓋了一個(gè)事實(shí)——富國銀行已經(jīng)披露了關(guān)于未來發(fā)展的大量細(xì)節(jié)——在精簡機(jī)構(gòu)的同時(shí),它已經(jīng)在一些強(qiáng)項(xiàng)領(lǐng)域上加倍下注了。

沙夫的團(tuán)隊(duì)總結(jié)了一年來的改革舉措,并且公布了一些其他措施,比如公布了一系列資產(chǎn)出售計(jì)劃,這些計(jì)劃將把富國銀行從“非核心”的業(yè)務(wù)中剝離出來。

首先是富國銀行的100億美元學(xué)生貸款項(xiàng)目和加拿大的設(shè)備融資業(yè)務(wù)。同時(shí),富國銀行還在考慮剝離其資產(chǎn)管理部門,該部門目前管理著逾6000億美元的機(jī)構(gòu)客戶資產(chǎn)。

沙夫在財(cái)報(bào)電話會議上表示:“我們將要退出的都是非常好的業(yè)務(wù)。但問題是,它們是不是最適合放在富國銀行內(nèi)部?”

在沙夫看來,住房貸款業(yè)務(wù)是要保留的,這是富國銀行的“生命線”,也是它主宰了幾十年的大市場。此外還要保留消費(fèi)銀行、個(gè)人理財(cái)和投資銀行業(yè)務(wù)——富國銀行相信,投行業(yè)務(wù)可以成為它的一個(gè)增長點(diǎn)。

為了保持利潤,富國銀行還將繼續(xù)“刀刃向內(nèi)”。

目前,富國已經(jīng)確定了80多億美元的長期節(jié)支目標(biāo)。裁員當(dāng)然也是必不可少的:去年第四季度,富國銀行裁掉了6400人,預(yù)計(jì)今年還會有更多裁員。富國銀行還計(jì)劃大幅削減辦公用房開支,預(yù)計(jì)總辦公面積將縮減20%。

同時(shí),富國銀行也在對分支網(wǎng)絡(luò)進(jìn)行“瘦身”。富國在2020年底擁有大約5000家分支機(jī)構(gòu),已經(jīng)少于2009年的6600家,它還計(jì)劃今年再關(guān)閉250家。

盡管改革計(jì)劃雄心勃勃,但它對公司整體增長的提振依然有限——除非它能讓監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)滿意,覺得它的改革已經(jīng)全面完成了。富國銀行及有關(guān)監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)以“法律限制”為由,拒絕了就取消“獎(jiǎng)金帽”的時(shí)間表一事發(fā)表評論。

沙夫?qū)Α敦?cái)富》雜志表示:“我理解大家的想法,大家想聽到的是,當(dāng)我們最終跨過這些事情時(shí),公司會變成什么樣子。”但除非富國的風(fēng)控機(jī)制讓監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)滿意,否則要想真正“跨過”這些事,只怕還得再等等 。

大概20年前,也就是沙夫還在芝加哥擔(dān)任第一銀行CFO的時(shí)候,他學(xué)起了吉他。在疫情“封城”期間,他重新聯(lián)系上了他的吉他老師,現(xiàn)在他每周都在通過Zoom上網(wǎng)課,練習(xí)藍(lán)調(diào)和搖滾。

“這東西很有創(chuàng)意,”他興奮地說:“你可以把它拿起來,并且用它創(chuàng)造一些東西,而且還和別人創(chuàng)造的東西不一樣,這在我看來非同尋常。”

就像彈吉他一樣,沙夫在富國銀行也試圖彈出一些新的、和諧的東西。但要將富國銀行這把“吉他”的弦調(diào)好,他還需要更多的時(shí)間。

打小井,打深井

為了在當(dāng)下的困境中生存下來,并且讓股東滿意,富國啟動了“精兵簡政”計(jì)劃。

由于監(jiān)管制裁限制了公司的增長能力,富國銀行選擇了剝離“非核心”部門,專注于最有前途的業(yè)務(wù)。CEO沙夫希望以下幾個(gè)部門能在形勢好轉(zhuǎn)后再次蓬勃發(fā)展。

消費(fèi)者和小企業(yè)銀行借貸

2020年收入:340億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:瑪麗·麥克、邁克爾·韋因巴赫

富國銀行是美國最大的住房抵押貸款機(jī)構(gòu)之一,該部門也是目前為止富國最大的業(yè)務(wù)板塊。最近的低利率已經(jīng)影響了該部門的收入。不過富國銀行還有4000多億美元的消費(fèi)貸款規(guī)模,以及強(qiáng)勁的車貸和信用卡業(yè)務(wù)。這些業(yè)務(wù)有更高的利率,而且應(yīng)該會隨著經(jīng)濟(jì)復(fù)蘇而復(fù)蘇。

理財(cái)和投資管理

2020年收入:145億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:巴里·薩默斯

截止到2020年底,富國銀行一共管理著2萬億美元資產(chǎn)——雖然它計(jì)劃出售6000億美元的機(jī)構(gòu)資產(chǎn)管理業(yè)務(wù),以便更好地專注于個(gè)人理財(cái)業(yè)務(wù)。

富國銀行的財(cái)富管理團(tuán)隊(duì)歷來不僅服務(wù)有錢人,也服務(wù)“大眾富裕階層”和中產(chǎn)階級客戶。沙夫很看好該部門與消費(fèi)貸款部門的協(xié)同效應(yīng):“大量進(jìn)入我們的分支機(jī)構(gòu)的客戶,都是有錢投資的。”他說。

企業(yè)和投資銀行

2020年收入:138億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:瓊恩·威斯

該部門包括1100億美元的商業(yè)地產(chǎn)板塊和大量的“C&I”貸款(即企業(yè)購置機(jī)械設(shè)備的貸款)。總體上看,富國銀行的商業(yè)貸和消費(fèi)貸差不多各占50%。雖然在企業(yè)和投資銀行領(lǐng)域,富國銀行的名聲不算顯赫,但根據(jù)Dealogic的數(shù)據(jù),它仍然是美國的第九大投行。沙夫的團(tuán)隊(duì)認(rèn)為,富國銀行有望在這一領(lǐng)域贏得市場份額。

銀行還能迎來好日子嗎?

受疫情影響,銀行業(yè)的復(fù)蘇速度十分緩慢,而且前路依然坎坷曲折。

2020年,包括銀行在內(nèi)的金融機(jī)構(gòu)的日子是很煎熬的,只不過這一點(diǎn)在一片大好的股市里沒有反映出來。(去年美股大盤增長了16%,而標(biāo)普500指數(shù)的金融板塊卻下跌了4%。)

受疫情影響,美國各大金融機(jī)構(gòu)都忙著想方設(shè)法支持他們的商貸和消費(fèi)貸客戶,從而嚴(yán)重影響了他們從利差中獲得的收益。

雖然目前情況貌似有所好轉(zhuǎn),但2021年的路,似乎也注定不會平坦。

復(fù)蘇緩慢且不均衡

美國銀行業(yè)的一些關(guān)鍵指標(biāo)一直比較強(qiáng)勁,比如抵押貸款需求和存款的增長等。股票牛市也帶動了交易收入,另外更多的經(jīng)濟(jì)刺激也有可能出臺。但高失業(yè)率和小企業(yè)的經(jīng)營困境,仍然注定了經(jīng)濟(jì)大環(huán)境在疫情緩解前不會根本好轉(zhuǎn)。在短期內(nèi),大銀行會更加強(qiáng)調(diào)盈利能力。而到目前為止,理財(cái)和投行業(yè)務(wù)相對來說對疫情還比較免疫。

利率觸底

為了應(yīng)對疫情對經(jīng)濟(jì)的影響,美聯(lián)儲將利率回歸到了接近于零的水平,并暗示接下來幾年都會如此。這就給銀行向客戶收取的利率設(shè)定了上限,并且導(dǎo)致了“凈息收入”的降低,而這恰恰是決定銀行收入的一個(gè)關(guān)鍵因素。(也就是銀行貸款收息和存款利息之間的差額。) 預(yù)計(jì)短期內(nèi),銀行將增加貸款規(guī)模,尤其是在抵押貸款領(lǐng)域,以彌補(bǔ)息差損失。

新政府的導(dǎo)向

銀行領(lǐng)導(dǎo)們大概不會懷念特朗普政府的朝令夕改和不可預(yù)測性,但他們或許會懷念特朗普的一些政策。

拜登有可能會改變特朗普對華爾街的“去監(jiān)管化”政策,并且取消對企業(yè)和高凈值個(gè)人的一些減稅。希望未來銀行能與監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)合作,為金融科技(比如加密貨幣和數(shù)字支付)和資本市場(比如直接上市和SPACs,即特殊目的收購)的新發(fā)展制定一些基本規(guī)則。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

本文原載于2021年二三月刊的《財(cái)富》雜志。

譯者:樸成奎

富國銀行CEO查爾斯·沙夫,照片拍攝于美國棕櫚灘的富國銀行辦公室。面對聯(lián)邦政府的處罰,富國銀行可用的招數(shù)已經(jīng)不多了。攝影:Erika Larsen

作為美國第三大銀行的CEO,查爾斯·沙夫?qū)Ω粐y行的潛力是抱有很大期望的。

他對這家銀行的優(yōu)勢如數(shù)家珍。首先,這是一家服務(wù)數(shù)百萬小企業(yè)的商業(yè)銀行;其次,它的消費(fèi)信貸平臺發(fā)放的抵押貸款,超過了全美各大銀行;另外,它的財(cái)富管理部門幫助不計(jì)其數(shù)的客戶擴(kuò)大了財(cái)富。

“它的核心競爭力,以及我們?yōu)橄M(fèi)者和企業(yè)所做的一切,都是非同一般的。”

他停頓了幾秒,實(shí)事求是地補(bǔ)充道:“但我們也犯了不少錯(cuò)誤。”

這一天是十月中旬,再過一天,沙夫執(zhí)掌富國銀行就滿一周年了。他坐在紐約長島家中一間木質(zhì)裝修的書房里,通過視頻會議軟件Zoom接受了我們的采訪。

由于疫情關(guān)系,這一年的大部分時(shí)間里,沙夫都是在這里發(fā)號施令,試圖完成扭轉(zhuǎn)富國銀行頹勢的任務(wù)。

富國銀行在美國金融界是個(gè)龐然大物,涉及多個(gè)業(yè)務(wù)領(lǐng)域,擁有26萬余名員工和大約7000萬名客戶。眼下正是富國銀行近170年歷史中最動蕩的時(shí)期,因?yàn)樽罱啻伪蝗恕白グ睘E用客戶的信任。

直到現(xiàn)在,富國銀行仍在為這些錯(cuò)誤付出代價(jià),不僅公司名聲受到了損失,還要承擔(dān)巨額罰款和嚴(yán)厲的政策制裁。其中最沉重的一擊,是美聯(lián)儲給它戴上了一頂1.95萬億美元的“資金帽”,即該銀行的資本不得超過上述上限。

受疫情影響,美國所有銀行都在超低利率中瑟瑟發(fā)抖,其他銀行還通過可以大量增加放貸和吸收資本儲備來“過冬”,但美聯(lián)儲給富國銀行的“緊箍咒”卻直接斷絕了它的這種可能性。

自2017年起,富國銀行的收入一直在穩(wěn)步下跌,在2020財(cái)年又下降了15%,只有723億美元,利潤也同步縮水了。而且自從爆出丑聞以來,它的股市表現(xiàn)一直不如其他大銀行。去年更是暴跌44%。

加拿大皇家銀行資本市場公司的美國銀行業(yè)證券策略主管杰拉德?卡西迪指出:“這家公司已經(jīng)千創(chuàng)百孔了,所有策略都必須拿到桌面上,好讓它恢復(fù)到一個(gè)投資者可以接受的盈利水平。”

當(dāng)現(xiàn)年55歲的沙夫接手時(shí),這份工作直接將他推上了金融業(yè)的風(fēng)口浪尖。

這已經(jīng)是他第三次擔(dān)任“財(cái)富500強(qiáng)”金融服務(wù)企業(yè)的CEO了,而且這份工作的報(bào)酬也是相當(dāng)豐厚的。根據(jù)富國銀行的股票激勵(lì)政策,他每年有可能能賺到2300萬美元。但富國銀行的CEO,也是全美國最難干的CEO。富國銀行是美國最大的借貸機(jī)構(gòu)之一,它感冒了,美國的宏觀經(jīng)濟(jì)都要打噴嚏。

沙夫一直以來的導(dǎo)師——摩根大通CEO杰米?戴蒙對《財(cái)富》表示,沙夫承擔(dān)的任務(wù)“事關(guān)重大”,并表示“如果他們成功了,對全國乃至整個(gè)銀行業(yè)都有好處。”

目前,沙夫正專心致志地在精簡機(jī)構(gòu)上下工夫——為了救命,只得先“縮水”、“瘦身”。

如果他成功了,他或許能將富國銀行從監(jiān)管的“緊箍咒”下解放出來,重現(xiàn)昔日榮光。如果他失敗了,面對一眾藍(lán)籌股競爭對手的后來居上,富國銀行可能將永遠(yuǎn)無法再現(xiàn)輝煌了。

在沙夫擔(dān)任CEO大約15個(gè)月后,為了了解富國銀行的改革情況,《財(cái)富》采訪了沙夫和富國銀行的高管,以及一些分析師、批評人士、行業(yè)競爭對手,還有沙夫以前的同事。

由于正逢多事之秋,富國又迎來了大規(guī)模的組織變革,加上一些重大失誤,人們不禁懷疑,沙夫是否有能力推動一次徹底的企業(yè)文化變革。

巴克萊銀行的高級證券研究分析師賈森?戈德堡表示: “讓這么大的一艘船掉頭需要很長時(shí)間,他正在學(xué)習(xí)。”

沙夫認(rèn)為,富國銀行還是有機(jī)會恢復(fù)原來的地位的。他表示:“我來的時(shí)候就很清楚,富國仍然有很好的發(fā)展機(jī)會,不過我們還有大量的工作要做。”

沙夫是在新澤西州的威斯菲德長大的,那里是紐約市的郊區(qū)。他父親是一名股票經(jīng)紀(jì)人,身邊也都是金融專業(yè)人士。從13歲時(shí)開始,沙夫已經(jīng)在曼哈頓的股票交易所里做一些后臺工作了。

在約翰霍普金斯大學(xué)讀本科時(shí),他最初的目標(biāo)是從事化學(xué)研究。不過讀大二的時(shí)候,他突然頓悟了:“當(dāng)時(shí)我在上物理化學(xué)課,我被關(guān)在一間實(shí)驗(yàn)室里,然后我對自己說:‘我不想一輩子待在一個(gè)連窗戶都沒有的地方。’”同時(shí)他意識到,在商業(yè)上,“你可以以一種完全不同的方式來創(chuàng)造事物。”

或許是命中注定,沙夫的一個(gè)親戚恰好認(rèn)識杰米?戴蒙的父親,當(dāng)時(shí)年輕的杰米·戴蒙還在巴爾的摩的商業(yè)信貸銀行里當(dāng)財(cái)務(wù)總監(jiān)。1987年,戴蒙將剛畢業(yè)的沙夫招入公司,他倆的工作關(guān)系就此持續(xù)了20多年。而這家商業(yè)信貸銀行就是花旗集團(tuán)的前身。

在杰米·戴蒙和桑迪?威爾領(lǐng)導(dǎo)下,沙夫在商業(yè)信貸銀行發(fā)展成為花旗集團(tuán)的過程中發(fā)揮了一系列作用。2000年,戴蒙擔(dān)任了美國第一銀行的首席執(zhí)行官,并任命沙夫?yàn)榈谝汇y行首席財(cái)務(wù)官。2004年,美國第一銀行與摩根大通合并后,沙夫又接手了摩根大通規(guī)模龐大的零售銀行業(yè)務(wù)。

戴蒙回憶道,沙夫能夠“處理我甩給他的任何任務(wù)”。

他說:“他能把事情做好,而且他的商業(yè)嗅覺也很靈敏。”隨著職務(wù)越來越高,沙發(fā)的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)才能也愈發(fā)出眾。

他還發(fā)現(xiàn),隨著戴蒙領(lǐng)導(dǎo)的公司規(guī)模越來越大,戴蒙的工作風(fēng)格也在發(fā)生變化。他說:“他總是挺身而出,而不是躲在別人后面。當(dāng)某件事出錯(cuò)時(shí),他總是親自處理。”

2012年,沙夫被Visa聘為首席執(zhí)行官,他的這些經(jīng)驗(yàn)終于有了用武之地。

當(dāng)時(shí),Visa還處于從一家發(fā)卡銀行協(xié)會所屬的私人企業(yè)向一家上市公司的艱難轉(zhuǎn)型中。到了Visa的舊金山總部后,沙夫發(fā)現(xiàn),這竟然還是一家“與世隔絕”的企業(yè),尚未“真正融入科技界”。

為了糾正這種情況,他與PayPal和Stripe等金融科技公司建立了合作關(guān)系,擴(kuò)展了Visa在數(shù)字支付領(lǐng)域的存在。事實(shí)證明,他的這一招是很有遠(yuǎn)見的。

現(xiàn)任Visa總裁瑞安?麥金納尼也是從摩根大通出來的,當(dāng)年跟著沙夫一起去了Visa。他表示:“當(dāng)時(shí)他做的很多基礎(chǔ)性工作,特別是跟電商有關(guān)的部分,現(xiàn)在我們都看到了成果。”

為了離東海岸的家人近一些,2016年,沙夫離開了Visa。在他任內(nèi),Visa的股價(jià)上漲了一倍多。

在Visa的經(jīng)歷,以及隨后在紐約梅隆銀行擔(dān)任CEO的經(jīng)歷,讓他明白了一個(gè)CEO的職責(zé)有多龐雜。沙夫感言:“沒有任何一個(gè)工作可以與之相比。整個(gè)企業(yè)的成敗都系于你一人,要指望你來定調(diào)子、培養(yǎng)企業(yè)文化……有些人喜歡這項(xiàng)工作,也有些人不喜歡。”而沙夫?qū)儆诘谝活悺?/p>

就在他離開Visa的時(shí)候,另一家總部位于舊金山的金融機(jī)構(gòu),卻爆出了一樁大丑聞。

關(guān)于富國銀行的虛假賬戶欺詐案,有很多細(xì)節(jié)都是有據(jù)可查的。

在極端扭曲的銷售文化驅(qū)動下,富國銀行員工未經(jīng)客戶同意,便為幾百萬個(gè)客戶開立了賬戶,并向他們銷售金融產(chǎn)品,這在當(dāng)時(shí)已經(jīng)成了整個(gè)公司的普遍現(xiàn)象。在房貸、車貸和財(cái)富管理業(yè)務(wù)上,也出現(xiàn)了類似的欺詐行為。

這種風(fēng)氣最終帶來了毀滅性的結(jié)果。

從2016年到2018年,聯(lián)邦監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)連發(fā)五道命令,曝光了富國銀行的管理亂象,同時(shí)對其施加了包括“資金帽”在內(nèi)的制裁。

監(jiān)管部門也沒有放過富國銀行高層的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)責(zé)任。2016年下臺的前任CEO約翰·斯坦普被處以1750萬美元罰款,并勒令其終身不得再從事銀行業(yè)。他的繼任者蒂姆·斯隆在2019年3月迫于政治壓力辭職。

美國眾議院金融服務(wù)委員會在去年一份報(bào)告中猛烈抨擊了富國銀行的董事會和管理層——丑聞都已經(jīng)曝光好幾年了,你們怎么還沒有解決公司的問題?

在欺詐丑聞之前,富國銀行算是少數(shù)幾家名聲還算不錯(cuò),而且全須全尾地挺過了2008年金融危機(jī)的美國銀行之一。一個(gè)個(gè)競爭對手都被金融危機(jī)打得灰頭土臉,富國銀行卻變得更加強(qiáng)大,還在金融危機(jī)期間以150億美元收購了美聯(lián)銀行。

但現(xiàn)在它已經(jīng)成了銀行業(yè)的眾矢之的。

在富國銀行奉獻(xiàn)了15年的老將瓊恩?威斯表示:“那時(shí)我們在忙增長,而其他銀行都專注于如何更好地經(jīng)營。在某種程度上,我們是自身成功的受害者,也許我們當(dāng)時(shí)就應(yīng)該多反省一下。”

2019年春天,富國銀行董事會開始尋找一位能夠真正發(fā)現(xiàn)問題并解決問題的CEO。在斯隆下臺6個(gè)月后,沙夫得到了這份工作。

他上任不久即表示,解決當(dāng)前面臨的監(jiān)管問題,“顯然是首要任務(wù)”。

在新CEO的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)下,富國銀行的運(yùn)營委員會召開了第一次會議,頭頭腦腦們聚集在圣路易斯的一間沒有窗戶的會議室里,討論如何扭轉(zhuǎn)當(dāng)前的不利局面。

威斯回憶道:“沙夫帶來了一個(gè)便箋本,而不是那種四五十頁圖文并茂的PPT,本子上做了大概一頁半的筆記,他一行一行地講解了他做生意的重點(diǎn),這是一次讓人放下戒備、較為隨意但又非常專注的討論,沒有任何廢話。”

實(shí)事求是和“不搞形式主義”,是很多人對沙夫的印象。他的直率就像他的滿頭白發(fā)一樣引人注目。但對一位需要經(jīng)常傳達(dá)壞消息并處理棘手事的CEO來說,坦率也是一筆重要的資產(chǎn)。

沙夫發(fā)現(xiàn),富國銀行最大的問題,是組織結(jié)構(gòu)異常松散,缺乏明確的權(quán)責(zé)界限,否則像賬戶欺詐這樣的現(xiàn)象是可以避免的。另外,富國銀行還缺乏大多數(shù)銀行已經(jīng)建立的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)和合規(guī)保障機(jī)制。

瑪麗?麥克已經(jīng)在富國銀行工作了26年,目前負(fù)責(zé)消費(fèi)者和小企業(yè)銀行業(yè)務(wù)。她表示:“當(dāng)時(shí),我們的內(nèi)部組織結(jié)構(gòu)確實(shí)較為封閉,各部門的業(yè)務(wù)較為獨(dú)立。其實(shí)我們應(yīng)該退一步審視一下,問問自己:‘那種情況,或者說那些弱點(diǎn),是不是真的在整個(gè)公司都存在?’但我們在這方面做得并不好。”

沙夫開始了大刀闊斧的改革,首先從高層人事變動開始。

目前沙夫的高管團(tuán)隊(duì)一共有17人,其中9人都是新聘用的。去年以前,富國銀行還沒有首席運(yùn)營官這個(gè)職位。沙夫設(shè)立了這個(gè)崗位,并且請來了他花旗集團(tuán)和摩根大通的老同事斯科特?鮑威爾來擔(dān)任首席運(yùn)營官。在此之前,鮑威爾曾擔(dān)任桑坦德銀行美國業(yè)務(wù)的CEO,任內(nèi)幫助桑坦德銀行妥善應(yīng)對了監(jiān)管部門的制裁。

其他幾位新人也多半是沙夫的老同事,CFO邁克?桑托馬西莫原本是紐約梅隆銀行的CFO;消費(fèi)貸款部門和財(cái)富管理部門的負(fù)責(zé)人邁克?魏巴赫和巴里?索莫斯,也都是沙夫在摩根大通的老相熟。

2020年2月,沙夫公布了一項(xiàng)重組計(jì)劃,將公司業(yè)務(wù)劃分為五個(gè)不同的部門。另外,他還重組了富國銀行的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)管理體系,這五個(gè)部門現(xiàn)在都有獨(dú)立的風(fēng)控官,通過這樣的制度設(shè)計(jì),來確保沒有任何一個(gè)部門敢搞小動作。

這樣一來,富國銀行在制度設(shè)計(jì)上吸取了其他銀行的最佳做法,使沙夫收獲了不少分析師的贊揚(yáng)。但后來發(fā)生的事表明,富國仍有大量工作要做。

去年2月,就在富國銀行的重組計(jì)劃公布的幾天后,美國司法部宣布,富國銀行將支付30億美元罰款,以達(dá)成丑聞相關(guān)指控的刑事調(diào)解。當(dāng)時(shí)人們普遍認(rèn)為,這將是富國銀行的最后一筆大額罰款,不過這也說明了丑聞對公司利潤的影響有多深。

另一件事也能說明丑聞給公司成本帶來了多大壓力:2020年,富國銀行在“專業(yè)服務(wù)/外部服務(wù)”上耗費(fèi)了67億美元,超過了年度總收入的9%。這筆費(fèi)用的大頭,無非是花在了官司善后的法務(wù)和咨詢費(fèi)上。

正所謂禍不單行,疫情一來,富國銀行只得將日常應(yīng)急工作放在長期改革前面。

沙夫連公司的人都沒完全認(rèn)熟,就只得坐困長島一隅,開始居家辦公。疫情期間,最重要的是讓幾千家分支機(jī)構(gòu)繼續(xù)開門營業(yè)。

即便是在封城期間,“每天也有100萬左右的顧客進(jìn)入我們的分支機(jī)構(gòu)。”瑪麗?麥克說。但要保證顧客的安全,并且讓非分支機(jī)構(gòu)的員工轉(zhuǎn)入遠(yuǎn)程辦公,這給公司的后勤工作提出了難題。

疫情期間,富國銀行又爆出了一個(gè)小丑聞,說明富國銀行的“整風(fēng)之路”依然任重道遠(yuǎn)。

去年,美國政府出臺了一些政策,以幫助那些因失去收入而無法償還抵押貸款的人。但有1600多名借款人投訴稱,富國銀行在沒有征得他們同意的情況下,給他們辦理了暫緩還款,而這種行為很有可能損害借款人的信用評級,影響他們的再次貸款能力。

在談到這次混亂時(shí),沙夫表示,富國已經(jīng)努力糾正了這個(gè)錯(cuò)誤。“在非常艱難的時(shí)期里,我們在試圖幫助客戶的時(shí)候犯了錯(cuò)。每個(gè)金融機(jī)構(gòu)都會犯錯(cuò)。”

富國銀行還被卷進(jìn)了人才多元化這種高度敏感的問題。

去年6月,他在一份備忘錄里,對銀行高層職位的人才儲備深度提出了質(zhì)疑。他在備忘錄中寫道:“不幸的現(xiàn)實(shí)是,有這種特殊經(jīng)驗(yàn)的黑人人才非常有限,”這也是一年來,對他個(gè)人聲譽(yù)威脅最嚴(yán)重的一件事了。

因?yàn)榫驮谏撤蜻M(jìn)行此番表述的幾周前,美國發(fā)生了黑人男子喬治·弗洛伊德被“跪殺”事件,結(jié)構(gòu)性的種族歧視成為全美上下高度關(guān)注的尖銳問題。沙夫的言論在此時(shí)顯得異常刺耳,不僅令許多員工感到不滿,也引發(fā)了外部人士的廣泛批評。

他們強(qiáng)調(diào),沙夫的很多左膀右臂都是他的老同事,而且是清一色的白人男性。雖然高管層里也有一名女性和兩名黑人男性,但都處于邊緣職位,而COO、CFO等關(guān)鍵崗位仍然是清一色的白人男性。

美國金融勞工組織改進(jìn)銀行委員會的尼克·韋納認(rèn)為:“我們看到的是,他用另一個(gè)孤立的團(tuán)體,取代了一個(gè)孤立的團(tuán)體。”

沙夫很快就為他的“黑人人才有限”言論道了歉,并表示,有關(guān)言論反映出“我自己無意識的偏見”。從那以后,富國銀行建立了一個(gè)專門負(fù)責(zé)多元化、代表性和包容性的部門。

其負(fù)責(zé)人克萊貝爾·桑托斯是去年11月剛從第一資本銀行跳槽來的,現(xiàn)在他也在高管委員會有了一席之地。幾個(gè)月后,沙夫?qū)@次“禍從口出”的事件開展了嚴(yán)肅的自我批評,并表示未來五年,要將公司高管隊(duì)伍中的黑人比例增加一倍,而且公司計(jì)劃將把部分高管的薪水與本部門員工隊(duì)伍的多元化程度掛鉤。

他似乎也敏銳地意識到,多年以來,他喜歡從外部請來神秘“強(qiáng)援”的做法,只會進(jìn)一步固化晉升渠道的不公。他表示:“看看這家公司的內(nèi)部代表性——而且大多數(shù)金融機(jī)構(gòu)都是這個(gè)樣子,你就會發(fā)現(xiàn),我們非常有必要采取不同的做法。”

乍一看,1月15日對富國銀行來說,只不過又是一個(gè)普通到沉悶的日子。

這一天,富國銀行2020年四季度的財(cái)報(bào),其營收低于分析師的預(yù)期,導(dǎo)致當(dāng)天股價(jià)下跌了近8%。然而由此帶來的沮喪情緒卻掩蓋了一個(gè)事實(shí)——富國銀行已經(jīng)披露了關(guān)于未來發(fā)展的大量細(xì)節(jié)——在精簡機(jī)構(gòu)的同時(shí),它已經(jīng)在一些強(qiáng)項(xiàng)領(lǐng)域上加倍下注了。

沙夫的團(tuán)隊(duì)總結(jié)了一年來的改革舉措,并且公布了一些其他措施,比如公布了一系列資產(chǎn)出售計(jì)劃,這些計(jì)劃將把富國銀行從“非核心”的業(yè)務(wù)中剝離出來。

首先是富國銀行的100億美元學(xué)生貸款項(xiàng)目和加拿大的設(shè)備融資業(yè)務(wù)。同時(shí),富國銀行還在考慮剝離其資產(chǎn)管理部門,該部門目前管理著逾6000億美元的機(jī)構(gòu)客戶資產(chǎn)。

沙夫在財(cái)報(bào)電話會議上表示:“我們將要退出的都是非常好的業(yè)務(wù)。但問題是,它們是不是最適合放在富國銀行內(nèi)部?”

在沙夫看來,住房貸款業(yè)務(wù)是要保留的,這是富國銀行的“生命線”,也是它主宰了幾十年的大市場。此外還要保留消費(fèi)銀行、個(gè)人理財(cái)和投資銀行業(yè)務(wù)——富國銀行相信,投行業(yè)務(wù)可以成為它的一個(gè)增長點(diǎn)。

為了保持利潤,富國銀行還將繼續(xù)“刀刃向內(nèi)”。

目前,富國已經(jīng)確定了80多億美元的長期節(jié)支目標(biāo)。裁員當(dāng)然也是必不可少的:去年第四季度,富國銀行裁掉了6400人,預(yù)計(jì)今年還會有更多裁員。富國銀行還計(jì)劃大幅削減辦公用房開支,預(yù)計(jì)總辦公面積將縮減20%。

同時(shí),富國銀行也在對分支網(wǎng)絡(luò)進(jìn)行“瘦身”。富國在2020年底擁有大約5000家分支機(jī)構(gòu),已經(jīng)少于2009年的6600家,它還計(jì)劃今年再關(guān)閉250家。

盡管改革計(jì)劃雄心勃勃,但它對公司整體增長的提振依然有限——除非它能讓監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)滿意,覺得它的改革已經(jīng)全面完成了。富國銀行及有關(guān)監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)以“法律限制”為由,拒絕了就取消“獎(jiǎng)金帽”的時(shí)間表一事發(fā)表評論。

沙夫?qū)Α敦?cái)富》雜志表示:“我理解大家的想法,大家想聽到的是,當(dāng)我們最終跨過這些事情時(shí),公司會變成什么樣子。”但除非富國的風(fēng)控機(jī)制讓監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)滿意,否則要想真正“跨過”這些事,只怕還得再等等 。

大概20年前,也就是沙夫還在芝加哥擔(dān)任第一銀行CFO的時(shí)候,他學(xué)起了吉他。在疫情“封城”期間,他重新聯(lián)系上了他的吉他老師,現(xiàn)在他每周都在通過Zoom上網(wǎng)課,練習(xí)藍(lán)調(diào)和搖滾。

“這東西很有創(chuàng)意,”他興奮地說:“你可以把它拿起來,并且用它創(chuàng)造一些東西,而且還和別人創(chuàng)造的東西不一樣,這在我看來非同尋常。”

就像彈吉他一樣,沙夫在富國銀行也試圖彈出一些新的、和諧的東西。但要將富國銀行這把“吉他”的弦調(diào)好,他還需要更多的時(shí)間。

打小井,打深井

為了在當(dāng)下的困境中生存下來,并且讓股東滿意,富國啟動了“精兵簡政”計(jì)劃。

由于監(jiān)管制裁限制了公司的增長能力,富國銀行選擇了剝離“非核心”部門,專注于最有前途的業(yè)務(wù)。CEO沙夫希望以下幾個(gè)部門能在形勢好轉(zhuǎn)后再次蓬勃發(fā)展。

消費(fèi)者和小企業(yè)銀行借貸

2020年收入:340億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:瑪麗·麥克、邁克爾·韋因巴赫

富國銀行是美國最大的住房抵押貸款機(jī)構(gòu)之一,該部門也是目前為止富國最大的業(yè)務(wù)板塊。最近的低利率已經(jīng)影響了該部門的收入。不過富國銀行還有4000多億美元的消費(fèi)貸款規(guī)模,以及強(qiáng)勁的車貸和信用卡業(yè)務(wù)。這些業(yè)務(wù)有更高的利率,而且應(yīng)該會隨著經(jīng)濟(jì)復(fù)蘇而復(fù)蘇。

理財(cái)和投資管理

2020年收入:145億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:巴里·薩默斯

截止到2020年底,富國銀行一共管理著2萬億美元資產(chǎn)——雖然它計(jì)劃出售6000億美元的機(jī)構(gòu)資產(chǎn)管理業(yè)務(wù),以便更好地專注于個(gè)人理財(cái)業(yè)務(wù)。

富國銀行的財(cái)富管理團(tuán)隊(duì)歷來不僅服務(wù)有錢人,也服務(wù)“大眾富裕階層”和中產(chǎn)階級客戶。沙夫很看好該部門與消費(fèi)貸款部門的協(xié)同效應(yīng):“大量進(jìn)入我們的分支機(jī)構(gòu)的客戶,都是有錢投資的。”他說。

企業(yè)和投資銀行

2020年收入:138億美元

負(fù)責(zé)人:瓊恩·威斯

該部門包括1100億美元的商業(yè)地產(chǎn)板塊和大量的“C&I”貸款(即企業(yè)購置機(jī)械設(shè)備的貸款)。總體上看,富國銀行的商業(yè)貸和消費(fèi)貸差不多各占50%。雖然在企業(yè)和投資銀行領(lǐng)域,富國銀行的名聲不算顯赫,但根據(jù)Dealogic的數(shù)據(jù),它仍然是美國的第九大投行。沙夫的團(tuán)隊(duì)認(rèn)為,富國銀行有望在這一領(lǐng)域贏得市場份額。

銀行還能迎來好日子嗎?

受疫情影響,銀行業(yè)的復(fù)蘇速度十分緩慢,而且前路依然坎坷曲折。

2020年,包括銀行在內(nèi)的金融機(jī)構(gòu)的日子是很煎熬的,只不過這一點(diǎn)在一片大好的股市里沒有反映出來。(去年美股大盤增長了16%,而標(biāo)普500指數(shù)的金融板塊卻下跌了4%。)

受疫情影響,美國各大金融機(jī)構(gòu)都忙著想方設(shè)法支持他們的商貸和消費(fèi)貸客戶,從而嚴(yán)重影響了他們從利差中獲得的收益。

雖然目前情況貌似有所好轉(zhuǎn),但2021年的路,似乎也注定不會平坦。

復(fù)蘇緩慢且不均衡

美國銀行業(yè)的一些關(guān)鍵指標(biāo)一直比較強(qiáng)勁,比如抵押貸款需求和存款的增長等。股票牛市也帶動了交易收入,另外更多的經(jīng)濟(jì)刺激也有可能出臺。但高失業(yè)率和小企業(yè)的經(jīng)營困境,仍然注定了經(jīng)濟(jì)大環(huán)境在疫情緩解前不會根本好轉(zhuǎn)。在短期內(nèi),大銀行會更加強(qiáng)調(diào)盈利能力。而到目前為止,理財(cái)和投行業(yè)務(wù)相對來說對疫情還比較免疫。

利率觸底

為了應(yīng)對疫情對經(jīng)濟(jì)的影響,美聯(lián)儲將利率回歸到了接近于零的水平,并暗示接下來幾年都會如此。這就給銀行向客戶收取的利率設(shè)定了上限,并且導(dǎo)致了“凈息收入”的降低,而這恰恰是決定銀行收入的一個(gè)關(guān)鍵因素。(也就是銀行貸款收息和存款利息之間的差額。) 預(yù)計(jì)短期內(nèi),銀行將增加貸款規(guī)模,尤其是在抵押貸款領(lǐng)域,以彌補(bǔ)息差損失。

新政府的導(dǎo)向

銀行領(lǐng)導(dǎo)們大概不會懷念特朗普政府的朝令夕改和不可預(yù)測性,但他們或許會懷念特朗普的一些政策。

拜登有可能會改變特朗普對華爾街的“去監(jiān)管化”政策,并且取消對企業(yè)和高凈值個(gè)人的一些減稅。希望未來銀行能與監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)合作,為金融科技(比如加密貨幣和數(shù)字支付)和資本市場(比如直接上市和SPACs,即特殊目的收購)的新發(fā)展制定一些基本規(guī)則。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

本文原載于2021年二三月刊的《財(cái)富》雜志。

譯者:樸成奎

Charlie Scharf, the CEO of America’s third-largest bank, is a man enamored with the potential of the company he leads. He sounds almost awestruck as he enumerates the forces at his disposal. There’s the commercial bank that serves millions of small businesses. There’s a consumer-lending platform that accounts for more mortgages than any other major bank. There’s a wealth management division that has helped countless customers expand their affluence. “The core franchise, and what we do for consumers and businesses, is extraordinary,” Scharf says.

He pauses before adding, matter-of-factly: “But we made a bunch of mistakes.”

It is mid-October, the day before Scharf’s first anniversary at the helm of Wells Fargo. The CEO is sitting in an elegant, wood-paneled study at his home on New York’s Long Island, speaking via a Zoom video link. For much of a pandemic-afflicted year, this house has been the hub from which Scharf has tackled one of the toughest turnaround assignments in business. Scharf oversees an enormous, multifaceted bank with more than 260,000 employees and some 70 million customers. It’s a company emerging from the most tumultuous period in its nearly 170-year history, one in which it got caught—on multiple occasions—flagrantly abusing the trust of those customers.

Wells Fargo continues to pay for those sins with a tarnished reputation and through the lingering impact of severe fines and sanctions. The most damaging of those is a Federal Reserve–imposed, $1.95 trillion cap on the bank’s assets. As the economy reels from the impact of the coronavirus, all banks are feeling the effects of ultralow interest rates that clobber their profit margins. But unlike its rivals, Wells can’t offset the impact by rapidly stepping up lending volume or attracting capital reserves—the asset cap prevents it. Wells Fargo’s revenue has steadily declined since 2017 and dropped another 15% in fiscal 2020, to $72.3 billion. Profits have shriveled, too, and its shares, which fell 44% last year, have consistently underperformed those of other big banks since the scandal erupted. “This company is a damaged company, and all strategies have to be put on the table to bring it back to a level of profitability that investors will find acceptable,” says Gerard Cassidy, head of U.S. bank equity strategy at RBC Capital Markets.

When he took the gig, Scharf, now 55, stepped into one of the most closely scrutinized positions in finance. It’s his third CEO stint at a Fortune 500 financial services company, and an extremely well-compensated one. He can earn up to $23 million annually, depending on stock incentives. It also ranks among the toughest chief executive jobs in America. Given Wells’ status as one of the biggest “Main Street” lenders, its overall health has implications for the broader economy too. Scharf’s longtime mentor, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, tells Fortune that the task Scharf signed up for is a challenge “too big to walk away from,” adding, “It’s better for the country and for the banking industry that they succeed.”

For now, Scharf is concentrating on creating a leaner, more focused institution—shrinking the bank in order to save it. If he succeeds in shepherding Wells Fargo out of regulatory purgatory, he may restore the luster of one of the grand old names of American banking. Should he fail, Wells could be permanently relegated to afterthought status among its blue-chip rivals.

Fortune spoke with Scharf and top Wells Fargo executives—as well as analysts, critics, industry rivals, and former colleagues of Scharf’s—to capture the state of the turnaround, some 15 months into the CEO’s tenure. It has been an eventful time that has featured sweeping organizational changes—along with high-profile missteps that fueled skepticism about whether Scharf can institute meaningful cultural change. “It takes a long time to turn around such a big ship,” says Jason Goldberg, a senior equity research analyst at Barclays. “He’s learning that.”

Scharf, for his part, sees a chance to restore the bank to its rightful place. “I came in with a clear understanding that the core franchise continued to be this great opportunity,” he says, “but that there was a tremendous amount of work to do.”

*****

Scharf grew up in Westfield, N.J., a New York suburb crowded with financial professionals like his father, a stockbroker. By age 13, Charlie was working back-office jobs at Manhattan brokerages. As an undergrad at Johns Hopkins, he initially had designs on becoming a research chemist—until he had a sophomore-year epiphany. “I was in physical chemistry, locked in a lab, when I said to myself, ‘I really don’t want to spend my life in a place without windows,’?” he recalls. In business, he realized, “you could create something in a very different way.”

As fate would have it, a relative of Scharf’s knew the father of a banker named Jamie Dimon, the young chief financial officer of Baltimore-based lender Commercial Credit. Dimon brought the recent grad on board in 1987—the start of a working relationship that would span more than 20 years. Scharf played a variety of roles under Dimon and Sandy Weill as they grew Commercial Credit into what eventually became Citigroup. When Dimon landed the top job at Bank One in 2000, he tapped Scharf as CFO. After Bank One merged with JPMorgan Chase in 2004, Scharf took the helm of Chase’s sprawling retail banking business.

Dimon recalls Scharf as able to “handle just about anything” Dimon threw at him: “He got stuff done; he had a good nose for cracking through the bull.” Scharf acquired the seasoning that came with ever-larger roles; he also saw Dimon’s job evolve as he led ever-larger companies. Of what he learned from Dimon as a leader, Scharf says, “He stands in front. He doesn’t hide behind people. He doesn’t look at others when something goes wrong.”

Scharf would put those lessons into practice in 2012, when Visa tapped him as CEO. Visa was still grappling with its 2008 transition from a private entity, owned by an association of card-issuing banks, to a publicly traded company. At Visa’s San Francisco headquarters, Scharf found what he describes as an “insular” business that “didn’t really engage with the technology community.” He aimed to rectify that, establishing relationships with fintechs like PayPal and Stripe that expanded Visa’s footprint in digital payments—a focus that proved prescient. Says current Visa president Ryan McInerney, a JPMorgan alum who followed Scharf to Visa: “A lot of the foundation he laid, especially as it relates to digital commerce, you’re seeing the results now.”

Scharf left Visa in 2016, seeking to be closer to his family on the East Coast—and leaving behind a company whose share price more than doubled during his tenure. His experience there, as well as a subsequent stint as CEO of custodian bank BNY Mellon, taught him how all-encompassing the chief’s role was. “There’s no job that’s comparable,” Scharf says. “The whole organization looks to you for the wins and the losses, for setting the tone and the culture?…?Some love it, and some don’t love it.” Scharf falls into the first category.

Around the time he was leaving Visa, another San Francisco–based company was reckoning with a scandal of tectonic proportions.

The details of Wells Fargo’s fake-accounts fraud debacle are well documented: Driven by a hyperaggressive sales culture, employees opened accounts for and sold financial products to millions of customers—without their approval. The problems were endemic across the company, with similar sharklike misconduct surfacing in Wells’ mortgage, auto lending, and wealth management businesses.

The fallout proved devastating. From 2016 through 2018, federal regulators hit Wells with five consent orders laying bare the institution’s mismanagement—along with sanctions that included the constraining asset cap. Regulators also held Wells’ leadership accountable: Former CEO John Stumpf, who stepped down after the scandal emerged in 2016, was eventually handed a $17.5 million fine and a lifetime ban from the banking industry. His successor, Tim Sloan, resigned under political pressure in March 2019. In a report last year, the House Financial Services Committee slammed Wells Fargo’s board and management for continually failing to address the company’s shortcomings, even years after the misdeeds came to light.

Wells Fargo had been one of the few American banks to emerge from the 2008 financial crisis with its reputation intact. As rivals stumbled, Wells grew stronger, as evidenced by its $15 billion mid-crisis acquisition of Wachovia. Now, it finds itself the bête noire of the banking sector. “We were growing while everyone else was focused on running themselves better,” says Jon Weiss, a 15-year Wells veteran who now leads the corporate and investment banking division. “We were to some degree victims of our own success, and maybe we could have used a bit more introspection.”

By spring 2019, Wells’ board was searching for a CEO who could lead the company in a long, hard look in the mirror. Six months after Sloan stepped down, Scharf got the job. Solving the bank’s regulatory issues, Scharf said shortly after his appointment, would be “clearly the first priority.”

*****

For the first meeting of Wells Fargo’s operating committee under the new CEO, its leaders gathered in a windowless conference room in St. Louis to address the daunting business of turning the bank around. “Charlie brought in a legal pad—not a PowerPoint presentation, not 40 pages of colored pictures the way that an investment bank would present—with a page and a half of notes, line by line, that he wanted to go through to explain the way he does business,” Weiss recalls. “It was a disarming, casual, but very focused discussion with no baloney.”

Matter-of-factness and a “no frills” demeanor are common threads in descriptions of Scharf; his directness can be as striking as his trademark shock of white hair. But plainspokenness can also be an asset for a chief executive with bad news to deliver and tough problems to solve.

The biggest problem Scharf identified at Wells Fargo was an exceptionally decentralized organization—one lacking the clear lines of accountability that might have prevented the fake-account fraud. The bank also lacked risk-and-compliance safeguards that most banks of comparable size already had. “We did have a relatively siloed organization, where you had intact businesses that were running a bit independently,” says Mary Mack, who has been with Wells for 26 years and now leads its consumer and small-business banking division. “I don’t think we did a very good job of stepping back and saying, ‘Could that condition or set of weaknesses actually exist across the entire company?’”

Scharf began a major overhaul, starting with turnover at the top. Nine of the 17 people now serving with Scharf on the bank’s senior leadership committee are new hires. Prior to last year, the role of chief operating officer didn’t exist at Wells Fargo. Scharf created it and recruited Scott Powell, a former colleague at Citi and JPMorgan, to fill it. Powell most recently served as CEO of Santander’s U.S. business, where he helped that bank cope with regulatory sanctions of its own. Several other new executives are also past colleagues of Scharf’s: CFO Mike Santomassimo had the same role at BNY Mellon; Mike Weinbach and Barry Sommers, who now head Wells’ consumer lending and wealth management divisions, respectively, are JPMorgan alumni.

In February 2020, Scharf unveiled a reorganization plan that redrew the company’s business lines across five distinct divisions. Just as important was a reconfiguration of Wells’ risk-management system: Each of the five divisions now has its own dedicated risk officer—a structure designed to ensure no unit of the bank is cutting corners.

Analysts hailed Scharf for bringing Wells Fargo in line with other banks’ best practices. But subsequent events offered persistent reminders of the work that remains to be done. Last February, just days after the reorganization’s unveiling, the Justice Department announced that Wells would pay $3 billion to settle criminal charges related to the accounts scandal. The consensus was that this would be Wells’ last major penalty, but it offered another stark example of the scandal’s erosion of the bank’s profits. Another sign of the lingering cost: In 2020, Wells Fargo spent $6.7 billion on “professional/outside services”—more than 9% of total revenue—the lion’s share of which reflects legal and consulting fees related to the post-scandal cleanup.

Meanwhile, the pandemic forced Wells Fargo to put daily emergencies ahead of long-term reforms. Scharf, still in the early days of meeting Wells’ workforce, found himself confined to his Long Island home office. Keeping the bank’s thousands of branches open was essential—even amid lockdowns, Wells had “1 million customers a day coming into our branches,” says Mack—but keeping them safe, and transitioning nonbranch employees to remote work, was a logistical obstacle course.

COVID-19 also triggered a mini-scandal that echoed the bank’s past misdeeds. After the government enacted mortgage relief measures to help people who couldn’t keep up with payments, no fewer than 1,600 borrowers complained that Wells Fargo had placed their loans in forbearance without their consent—an act that could actually harm the borrowers’ credit ratings and prevent them from refinancing. “We were erring on the side of trying to help customers in a very difficult time,” Scharf says of the snafu, which the bank scrambled to correct. “Every institution makes mistakes.”

The bank also entangled itself in difficult questions around diversity. No incident from his first year at Wells Fargo proved more threatening to Scharf’s reputation than comments he made in a June memo announcing new diversity initiatives, in which he cast doubt on the depth of talent available for top jobs at the bank. “The unfortunate reality is that there is a very limited pool of Black talent to recruit from with this specific experience,” he wrote.

With nationwide awareness of structural racism honed to a sharp edge by the killing of George Floyd just a few weeks earlier, the comments were particularly tone-deaf. They upset many employees and drew widespread condemnation from critics outside the bank. They also highlighted the whiteness and maleness of the ranks of former colleagues from which Scharf had recruited many of his lieutenants. While his nine hires on the leaders’ committee include a woman and two Black men, the highest-ranking ones, including the COO and CFO, are white men. “What we’ve seen is that he’s replaced one insular group with another,” says Nick Weiner of the financial industry labor group Committee for Better Banks.

Scharf quickly apologized for the “l(fā)imited pool” comments, saying they reflected “my own unconscious bias.” Wells has since created a diversity, representation, and inclusion group: Its chief, Kleber Santos, who joined the company in November from Capital One, sits on the senior leadership committee. Months later, Scharf is solemn and cautious as he discusses the gaffe. He points to the company’s goal of doubling Black representation in its senior ranks over the next five years, as well as its plan (announced in his June memo) to tie some of executives’ compensation to the diversity of their business lines. He also seems acutely aware that the hire-who-you-know approach that he has relied on for years has also perpetuated inequities. “When you look at the representation inside this company—and this is true of most financial institutions—there’s a tremendous need to do things differently,” he says.

******

January 15 at first glance seemed like just another dreary day for Wells Fargo. Disclosing earnings for the fourth quarter of 2020, the bank reported revenues that missed analysts’ estimates, and shares fell nearly 8% on the day. The general gloom obscured the fact that Wells Fargo also revealed substantial details about its future—as a leaner institution doubling down on what it does well.

Recapping some moves and unveiling others, Scharf’s team listed a series of asset sales that would extract the bank from “noncore” businesses. On their way out are Wells Fargo’s $10 billion student loan portfolio and its Canadian equipment-financing business. The bank is also looking to off-load its asset management arm, which oversees more than $600 billion for institutional clients. “The businesses that we’re exiting are perfectly good businesses,” Scharf said on the earnings call. “The question is, are they best housed within Wells Fargo?”

In Scharf’s vision, that housing is reserved for bread-and-butter businesses that Wells has dominated for decades—including consumer banking and personal wealth management—as well as for investment banking, where the company believes it can rise in the ranks.

To sustain profits while it pivots, Wells Fargo will keep cutting. The company has identified more than $8 billion in long-term cost savings, of which job cuts are part and parcel: Wells reduced headcount by 6,400 in the fourth quarter, and more cuts are expected this year. The bank plans to dramatically reduce its real estate footprint, scaling down its office space by up to 20%. A downsizing of its branch network is well underway. Wells Fargo had about 5,000 branch locations at the end of 2020, down from 6,600 in 2009, and it plans to close 250 more this year.

Ambitious as it is, the plan will likely leave Wells Fargo running in place insofar as overall growth is concerned—until it can satisfy regulators that it has fully reformed. The bank and its regulators refuse to comment on a timeline for the removal of the asset cap, citing legal constraints. “I understand people’s desire to hear exactly what the company can look like when we get beyond these things,” Scharf tells Fortune. But until his risk-control regime impresses the authorities, “beyond” will have to wait.

Some 20 years ago, while living in Chicago as CFO at Bank One, Scharf began taking guitar lessons. During the pandemic lockdown, he reconnected with his old instructor, and Scharf now studies with him over Zoom once a week, playing blues and rock. “It’s creative,” he enthuses. “The idea that you can pick up [a guitar] and make something out of it, differently than someone else who you hand the same device to, to me is just an extraordinary thing.” Scharf is committed to coaxing something new and harmonious out of Wells Fargo. But it’s going to take quite a while longer to get the instrument back in tune.

*****

Digging smaller, deeper wells

To survive its current woes and keep shareholders happy, a big bank plans to downsize.

With regulatory sanctions limiting its ability to grow, Wells Fargo has been shedding “noncore” units to focus on its most promising businesses. Here are the units that CEO Charlie Scharf hopes will help the bank thrive again in better times.

Consumer and small-business banking and lending

2020 revenue: $34 billion

Heads: Mary Mack and Michael Weinbach

Wells Fargo has one of the largest home mortgage businesses in the U.S., and this division is Wells’ biggest business segment by far. Falling interest rates have hurt the division’s revenue as of late. But the bank’s $400-billion-plus consumer loan portfolio also includes strong auto-financing and credit card businesses that command higher interest rates and should perk up as the economy improves.

Wealth and investment management

2020 revenue: $14.5 billion

Head: Barry Sommers

Wells Fargo managed $2 trillion in total assets at the end of 2020—though it plans to sell its $600 billion institutional asset management business, the better to focus on individuals. Wells’ wealth management team has historically served “mass affluent” and middle-class customers as well as richer ones. Scharf sees the division synergizing with consumer lending: “Huge numbers of customers who come into our branches have money to invest,” he says.

Corporate and investment banking

2020 revenue: $13.8 billion

Head: Jon Weiss

This division includes a $110 billion commercial real estate portfolio and a big stake in “C&I” loans (financing for businesses buying equipment and machinery). Overall, the bank’s loans are split nearly 50/50 between commercial and consumer lending. While it’s not a household name in the field, Wells Fargo is still the ninth-biggest investment bank in the U.S., according to Dealogic, and Scharf’s team sees that as a business in which it could win market share.

*****

Will life get better for banks?

Banks have been slow to recover from the COVID recession—and the road ahead looks rocky.

Financial firms, banks included, had a rough 2020 that wasn’t reflected by the country’s soaring stock markets. (The S&P 500’s financials sector lost 4% in 2020, compared with a 16% gain for the broader market.) The coronavirus pandemic forced America’s largest financial institutions to retool on the fly, leaving them scrambling to support their commercial and consumer borrowers, and undermining the income they made from interest rate spreads. Though sentiment has improved, 2021 looks like it will be far from a stroll.

A slow, uneven recovery

Some key indicators for banks, including mortgage demand and deposit growth, have remained strong. A resurgent bull market has driven trading revenues, and more economic stimulus seems likely. But high unemployment and lingering woes for small businesses remain burdensome headwinds, with no clear end in sight until COVID-19 abates. In the short run, big banks will emphasize their profitable—and thus far, relatively pandemic-proof—wealth management and investment banking businesses.

Rock-bottom interest rates

The Fed returned rates to near zero to deal with economic fallout from the pandemic, and it has signaled that they could remain there for years to come. That puts a ceiling on the rates banks can charge customers and reduces “net interest income,” a key driver of revenues. (It’s the difference between what banks earn on loans and what they pay out on deposits.) In the near term, expect banks to step up loan volume to make up for what they’re losing in interest, especially in the mortgage space.

New management in Washington

Bank leaders won’t miss the volatility and unpredictability of the Trump administration, but they may find themselves feeling nostalgic for some of its policies. President Biden will likely seek a reversal of Trump’s pro–Wall Street deregulatory agenda, as well as the undoing of some tax cuts for corporations and high-net-worth individuals. Look for banks to team up with regulators to lay ground rules for new developments in fintech (like cryptocurrencies and digital payments) and capital markets (such as direct listings and SPACs).

This article appears in the February/March 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline “Busted stagecoach: Can Charlie Scharf—or anyone—fix Wells Fargo?”