40年前,一位69歲的總統候選人站在克利夫蘭的辯論臺上,距離現任總統站的位置只有15英尺遠。他轉向電視觀眾,提出了似乎一夜之間改變選情的問題:“你過得比四年前好嗎?”

那是1980年10月28日,此前民意調查顯示,加州前州長共和黨人羅納德·里根和時任美國總統吉米·卡特兩位候選人競爭非常激烈,最新一次民調幾乎平分秋色。但當晚90分鐘的友好交流結束時,里根拋出的問題瞬間讓局勢明朗。當時,美國經濟在“滯脹”的沉重壓力下一蹶不振,大致可以理解為“一切都很糟糕”,失業率高達7.5%,通脹率飆升,汽油價格在之前一年里攀升了超過三分之一。號稱“偉大溝通者”的里根幾句話便點出了陰暗現實,一周后他獲得壓倒性優勢,50個州拿下了44個州,順利入主白宮。

四十年后,又一次遭逢總統大選的風口浪尖,當年里根提出的問題似乎還是最能觸動選民。或許你猜到了,一些民調機構確實提出了同樣的問題。9月英國《金融時報》(Financial Times)和彼得森基金會(Peterson Foundation)的調查發現,與四年前相比,35%的美國選民感覺現在的財務狀況更好,31%的人感覺更糟。后來蓋洛普(Gallup)的一項民意調查結果則更加樂觀,明顯多數登記投票者(56%)表示現在過得更好。從兩項調查結果來看,似乎對與前副總統拜登對決的特朗普來說都是好消息。

但意外仍然存在,畢竟僅憑調研很難預測選民實際的投票結果。“我們做了很多研究,從來沒真正發現人們的財務狀況跟投票結果之間有聯系。”杰弗里·瓊斯說,他負責蓋洛普美國民調業務,也包括之前提到的“是否過得更好”調查。“人們投票時并不會完全考慮自身利益,而是真正從社會出發。也就是說,他們更關心社會實際情況,而不是只看自身處境。”他說。

瓊斯說,蓋洛普的三項調查預測大選結果更準,相關調查可以判斷美國人對整體經濟的信心、對美國現狀的滿意程度,以及對總統的認可程度,而且看的是全國總體情況。(在每項里,總統的支持率目前都偏低,尤其是跟之前贏得連任的總統相比。)

那么,選民面臨的根本問題并不是“我過得更好嗎?”而是“我們過得更好嗎?”這也正是40年前里根提問的真正重點,然而該事實常常遭到忽視。1980年里根對電視觀眾進一步發問時就提到:

你去商店買東西比四年前方便嗎?美國失業率是比四年前高還是低?美國在全世界受尊敬的程度跟以前一樣嗎?你覺得我們的安全程度像四年前一樣嗎?

現在的美國選民正在面臨更多的問題,也許會更深刻地影響美國的國民認同,包括我們共同的使命感、對政府和社會機構的信任,甚至是交談和傾聽的方式。當然每次選舉中,選民都會不可避免地根據意識形態、哲學或道德做出個人選擇。不過,今年各政治派別的選民投票前都應該問一個基本問題:比起四年前,美國是否更加團結?

我還是我們

“不管任何時候,也不管在哪里的社會,人性都是統治政治的基本力量。”邁克·萊維特說,他曾經三次當選猶他州的州長,后來在小布什政府擔任美國衛生和公眾服務部(U.S. Health and Human Services)的部長。“我過得更好嗎?”以及“我們過得更好嗎?”確實能夠代表個人自由和安全之間的沖突。為了獲得其中之一,不得不放棄另一項。保守派共和黨人萊維特認為,自由和安全兩大永恒目標之間的競爭乃正當合理,甚至必要。但他擔心競爭太過殘酷,不過他也辯稱,尖酸刻薄的言辭累計遠不止過去四年時間。“我們發現身處兩個極端的人們似乎都愿意越界,打破民主的盟約。這讓人不適,也使人害怕,因為這與社會上公認的(契約)并不一致。”

皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)的數據顯示,左翼和右翼、民主黨和共和黨之間的分歧越發嚴重。盡管主要政黨在某些問題上的分歧越來越大,但最讓人擔心的并非意識形態,而是關乎個人。皮尤中心的政治研究主任卡羅爾·多爾蒂表示:“黨派反感是指,我不僅不同意反對黨,對該黨派的人看法也相當負面,20世紀90年代中期以來黨派反感現象一直在加劇。”多爾蒂說,2016年各種負面情緒開始激增。皮尤研究中心的數據顯示,認為民主黨人比一般美國人道德敗壞的共和黨人比例從2016年的47%上升到2019年的55%。民主黨人認為共和黨人道德敗壞的比例則上升了12個百分點,從35%上升到47%。皮尤調查顯示,近三分之二(63%)的共和黨人表示,民主黨人比一般美國人“不愛國”(23%的民主黨人認為共和黨人不夠愛國),而且兩黨里認為對手黨比一般人“心胸狹窄”或“懶惰”的比例也在攀升。兩黨認為分歧在擴大的人都占壓倒性多數,約四分之三的共和黨人和民主黨人承認,探討對方觀點時,“無法就基本事實達成一致”。皮尤研究中心發現,令人沮喪的是,如果涉及放棄任何利益,兩黨里都有很大比例成員(53%的共和黨人和41%的民主黨人)不希望領導人與對方尋求“共同基礎”。

多爾蒂強調,皮尤的最新研究是在總統大選前一年和疫情之前進行。“雖然無從推斷……但相關負面情緒可能惡化。”他指出。

“這是一場為美國靈魂的斗爭,沒有哪方能夠獲勝,主要看另一方的威脅。”新美國研究基金會(New America foundation)的政治改革項目高級研究員、政治科學家李·德魯特曼說道。“美國有一半人相信,如果另一半人掌權,國家是不合法的,而且有極大破壞性。”德魯特曼的書《打破兩黨厄運循環:美國多黨民主的案例》(Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America)已經于今年1月出版,書中認為不斷升級的超黨派主義已經將政治“簡化”為我們與他們,以及善與惡的二元對立。

德魯特曼表示,特朗普的言論是激化雙方長期積累憤怒的“催化劑”。特朗普入主白宮后,在競選集會上發出的激烈呼吁并未結束。相關言論聲量越來越大,也越發激烈,還在社交媒體上引發共鳴。埃默里大學(Emory University)的政治學教授阿蘭·阿布拉莫維茨說:“他從吹狗哨變成了拿著大喇叭喊”——從悄悄挖掘種族、種族和黨派的恨意,變成體育場里的大合唱。

馬里蘭大學(University of Maryland)的政府與政治副教授、《不文明協議:政治如何成為我們的身份》(Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity)一書的作者利利亞娜·梅森說,特朗普超高分貝大喇叭轟鳴的效果遠遠超出了“集會”,這種行為鼓勵了以政治為基礎的暴力,甚至變得正常化。她指出,美國“反移民”仇恨團體增加,與政客反移民言論同步就是例子。(非營利機構南方貧困法律中心表示,2014年以來,類似激進組織的數量增加了超過一倍。)“很多人警告稱會出現激進的暴力行為,主要是右翼挑起,尤其是在2020年大選前后。”梅森說,“不過美國各大城市已經有全副武裝的士兵巡邏。”10月聯邦調查局(FBI)披露,一些自稱民兵組織的厚顏無恥之徒策劃綁架了密歇根州州長格雷琴·惠特默,潛在的危險可從中一瞥。梅森表示,這些“都是2016年難以想象的”。

長長的待辦清單

盡管負面的黨派偏見導致美國社會結構撕裂,也增加了立法的挑戰性,尤其是聯邦層面“想做任何事,都得建立某種程度上的跨黨派同盟,”阿布拉莫維茨說。德魯特曼表示,實際問題甚至更嚴重。“美國制度里的根本沖突之一是,政治體制的出發點是鼓勵廣泛妥協,而政黨制度下達成妥協很難。所以,從一開始選舉和執政激勵機制就是不同的兩套制度。”政治摩擦升級只會擴大兩者之間的差別。

為了下一個世紀繼續繁榮發展,而且世界要比以往更具競爭力也更經濟,美國人必須投資自身,就像企業為了發展要自我投資一樣。這意味著為再就業計劃和關鍵基礎設施重建提供資金,具體操作起來涉及面很廣,從修復破損的道路和橋梁到建設先進的5G電信網絡均包括在內。社會保障體系的不穩定性也未減輕,需要以某種方式修正。我們要控制失控的醫保費用,控制仍然在肆虐的疫情,更要為今后的疫情做好準備。還有更棘手的問題要面對,包括應對氣候變化、刑事司法改革、制定既能夠推動產業發展和美國安全又可以維護公平感的移民政策等。到最后,我們還得想辦法幫助因疫情封鎖失業的數百萬人重返工作崗位(參見我們的選舉方案)。要做的事情可不少。

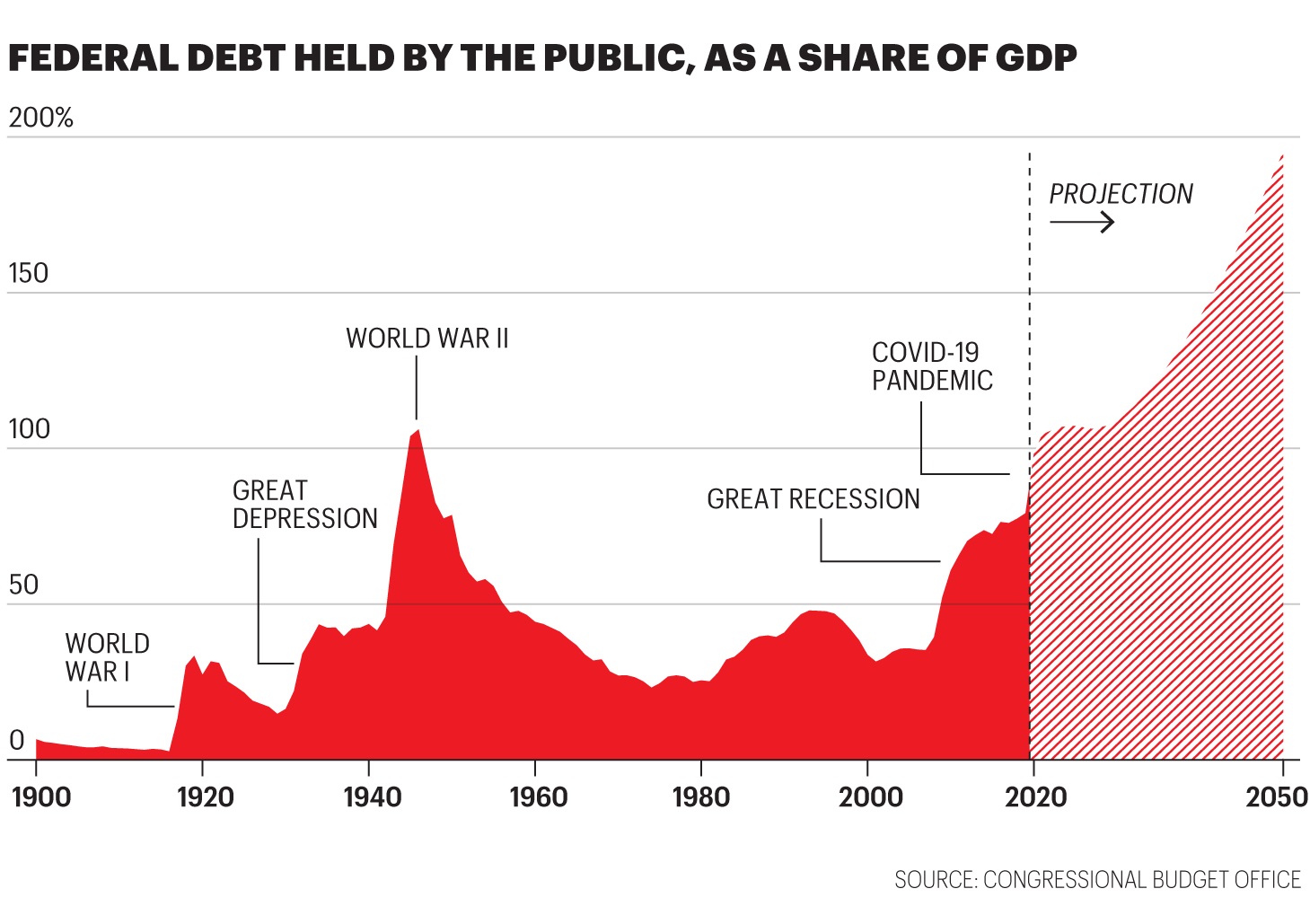

為待辦事項花錢可以說是更加艱巨的挑戰,兩黨揮金如土的領導人已經掏空了美國的錢包,而人們已經窮到快穿不起褲子。國會預算辦公室(見圖表)的數據顯示,到2023年公眾持有的聯邦債務將達到美國GDP的106%,而且屆時起紅線將繼續上升。解決問題需要創造性和雄心,意味著交戰雙方要盡棄前嫌共同努力。

這也意味著我們也要刺激美國商業增長。“如果說解決辦法就是創新,聽起來可能有點偏學術,也有點空想。”哥倫比亞大學資本主義與社會中心(Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University)的主任,2006年諾貝爾經濟學獎得主埃德蒙·菲爾普斯說。“但老實說,如果不能推動經濟發展得比過去40年或50年好,今后還能夠有多少進展真不一定。”菲爾普斯說,很高興看到企業開始積極抵制特朗普政府的關稅以及“阻礙企業開發產品所需人才”的移民政策。菲爾普斯特別希望下一屆政府能積極開展國際貿易。“國際貿易可能是美國商業部門新能源的來源。對就業、工資和其他方面都大有裨益。”他說。

微軟(Microsoft)的董事會成員、紐約私募股權公司Clayton Dubilier&Rice的合伙人桑迪·彼得森同樣對特朗普的移民政策很失望。她說:“如果我們不能齊心協力,美國的創新引擎將不復存在,創新引擎就是吸引全世界最聰明的人,創造令人驚艷的新產品。人們不再來這里學習,由于拿不到簽證,人們也無法來這工作。”彼得森曾經擔任強生(Johnson & Johnson)的全球董事長,她還表示,吸引海外人才“是長期以來推動美國經濟增長的原因,我們卻搞砸了。”

選民在這方面面臨的挑戰是,思考解決問題的最佳辦法,是再給特朗普一次機會,還是換個人重新開始。

信任和信譽

無論2021年1月20日誰上臺,都將面臨另一項緊迫任務:重建對政府機構本身的信任。過去四年里,疾病預防控制中心(CDC)、食品與藥品管理局(FDA)和司法部(Justice Department)之類過去被認為無黨派且不受政治壓力影響的機構,似乎都對白宮唯命是從,受到很多人質疑。新美國研究基金會的德魯特曼說:“之前這些機構都是中立的仲裁者,如果政治體系中人們能夠就基本的程序公平達成一致,并接受合理的反對意見,這些機構就可以保持獨立。”但身處狂熱的超黨派時代,理想的政治體系似乎已經不復存在。

馬里蘭大學的梅森表示,內訌對國家安全造成影響。她提醒說,喬治·華盛頓總統在告別演說中曾經發出警告。“如果允許派系存在,就可能自相殘殺,最終導致國家受到外部干涉;如果制造非常嚴重的黨派分歧,會使國家變弱,其他國家要攪亂美國也更容易。”梅森說。

史汀森中心(Stimson Center)是研究全球安全和其他關鍵問題的無黨派智庫,其總裁兼首席執行官布萊恩·芬萊對此表示贊同。“現在世界上的對手已經發現了美國制度的根本弱點。”芬萊說。“他們利用黨派分歧,也通過讓孩子們相信《華盛頓郵報》(Washington Post)不可信,充分利用了發現的技術弱點。我們的對手越來越聰明,現在還在攻擊選舉,就像在魚缸里點殺金魚一樣簡單。他們不需要向美國派遣武裝人員,在地下室的電腦上就能破壞。”

防御此類非同步戰爭很困難。如果沒有同盟、關系和協議就更難。美國早已簽訂多邊協議,阻止冷戰中的蘇聯擴張和侵略,限制核武器在世界各地擴散,阻止非法捕魚,當然也要出售更多的美國商品。

然而過去四年里,特朗普退出了多個重要的同盟,還威脅要“終止”美國與世界衛生組織(World Health Organization)的聯系(而且是在全球疫情泛濫期間),1948年世界衛生組織由美國倡議并協助成立。他還破壞了跨太平洋伙伴關系(TPP)貿易協定,芬雷說。

美國退出了里根總統1987年與蘇聯總理戈爾巴喬夫簽署的《中程核武器條約(INF)》(Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty),當年正是該條約推動冷戰結束。美國放棄了兩黨廣泛支持的《開放天空條約》(Open Skies Treaty),特朗普還讓美國退出了應對氣候變化的《巴黎協議》(Paris Agreement)。

對于美國的健康、繁榮和安全,以上諸多舉動更多都是自我傷害,也是選民投票時需要考慮的問題。最后簡單地說吧,我們比四年前過得更好,還是應該尋求改變了?(財富中文網)

本文登載于《財富》雜志2020年11月刊。

譯者:夏林

40年前,一位69歲的總統候選人站在克利夫蘭的辯論臺上,距離現任總統站的位置只有15英尺遠。他轉向電視觀眾,提出了似乎一夜之間改變選情的問題:“你過得比四年前好嗎?”

那是1980年10月28日,此前民意調查顯示,加州前州長共和黨人羅納德·里根和時任美國總統吉米·卡特兩位候選人競爭非常激烈,最新一次民調幾乎平分秋色。但當晚90分鐘的友好交流結束時,里根拋出的問題瞬間讓局勢明朗。當時,美國經濟在“滯脹”的沉重壓力下一蹶不振,大致可以理解為“一切都很糟糕”,失業率高達7.5%,通脹率飆升,汽油價格在之前一年里攀升了超過三分之一。號稱“偉大溝通者”的里根幾句話便點出了陰暗現實,一周后他獲得壓倒性優勢,50個州拿下了44個州,順利入主白宮。

四十年后,又一次遭逢總統大選的風口浪尖,當年里根提出的問題似乎還是最能觸動選民。或許你猜到了,一些民調機構確實提出了同樣的問題。9月英國《金融時報》(Financial Times)和彼得森基金會(Peterson Foundation)的調查發現,與四年前相比,35%的美國選民感覺現在的財務狀況更好,31%的人感覺更糟。后來蓋洛普(Gallup)的一項民意調查結果則更加樂觀,明顯多數登記投票者(56%)表示現在過得更好。從兩項調查結果來看,似乎對與前副總統拜登對決的特朗普來說都是好消息。

但意外仍然存在,畢竟僅憑調研很難預測選民實際的投票結果。“我們做了很多研究,從來沒真正發現人們的財務狀況跟投票結果之間有聯系。”杰弗里·瓊斯說,他負責蓋洛普美國民調業務,也包括之前提到的“是否過得更好”調查。“人們投票時并不會完全考慮自身利益,而是真正從社會出發。也就是說,他們更關心社會實際情況,而不是只看自身處境。”他說。

瓊斯說,蓋洛普的三項調查預測大選結果更準,相關調查可以判斷美國人對整體經濟的信心、對美國現狀的滿意程度,以及對總統的認可程度,而且看的是全國總體情況。(在每項里,總統的支持率目前都偏低,尤其是跟之前贏得連任的總統相比。)

那么,選民面臨的根本問題并不是“我過得更好嗎?”而是“我們過得更好嗎?”這也正是40年前里根提問的真正重點,然而該事實常常遭到忽視。1980年里根對電視觀眾進一步發問時就提到:

你去商店買東西比四年前方便嗎?美國失業率是比四年前高還是低?美國在全世界受尊敬的程度跟以前一樣嗎?你覺得我們的安全程度像四年前一樣嗎?

現在的美國選民正在面臨更多的問題,也許會更深刻地影響美國的國民認同,包括我們共同的使命感、對政府和社會機構的信任,甚至是交談和傾聽的方式。當然每次選舉中,選民都會不可避免地根據意識形態、哲學或道德做出個人選擇。不過,今年各政治派別的選民投票前都應該問一個基本問題:比起四年前,美國是否更加團結?

我還是我們

“不管任何時候,也不管在哪里的社會,人性都是統治政治的基本力量。”邁克·萊維特說,他曾經三次當選猶他州的州長,后來在小布什政府擔任美國衛生和公眾服務部(U.S. Health and Human Services)的部長。“我過得更好嗎?”以及“我們過得更好嗎?”確實能夠代表個人自由和安全之間的沖突。為了獲得其中之一,不得不放棄另一項。保守派共和黨人萊維特認為,自由和安全兩大永恒目標之間的競爭乃正當合理,甚至必要。但他擔心競爭太過殘酷,不過他也辯稱,尖酸刻薄的言辭累計遠不止過去四年時間。“我們發現身處兩個極端的人們似乎都愿意越界,打破民主的盟約。這讓人不適,也使人害怕,因為這與社會上公認的(契約)并不一致。”

皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)的數據顯示,左翼和右翼、民主黨和共和黨之間的分歧越發嚴重。盡管主要政黨在某些問題上的分歧越來越大,但最讓人擔心的并非意識形態,而是關乎個人。皮尤中心的政治研究主任卡羅爾·多爾蒂表示:“黨派反感是指,我不僅不同意反對黨,對該黨派的人看法也相當負面,20世紀90年代中期以來黨派反感現象一直在加劇。”多爾蒂說,2016年各種負面情緒開始激增。皮尤研究中心的數據顯示,認為民主黨人比一般美國人道德敗壞的共和黨人比例從2016年的47%上升到2019年的55%。民主黨人認為共和黨人道德敗壞的比例則上升了12個百分點,從35%上升到47%。皮尤調查顯示,近三分之二(63%)的共和黨人表示,民主黨人比一般美國人“不愛國”(23%的民主黨人認為共和黨人不夠愛國),而且兩黨里認為對手黨比一般人“心胸狹窄”或“懶惰”的比例也在攀升。兩黨認為分歧在擴大的人都占壓倒性多數,約四分之三的共和黨人和民主黨人承認,探討對方觀點時,“無法就基本事實達成一致”。皮尤研究中心發現,令人沮喪的是,如果涉及放棄任何利益,兩黨里都有很大比例成員(53%的共和黨人和41%的民主黨人)不希望領導人與對方尋求“共同基礎”。

多爾蒂強調,皮尤的最新研究是在總統大選前一年和疫情之前進行。“雖然無從推斷……但相關負面情緒可能惡化。”他指出。

“這是一場為美國靈魂的斗爭,沒有哪方能夠獲勝,主要看另一方的威脅。”新美國研究基金會(New America foundation)的政治改革項目高級研究員、政治科學家李·德魯特曼說道。“美國有一半人相信,如果另一半人掌權,國家是不合法的,而且有極大破壞性。”德魯特曼的書《打破兩黨厄運循環:美國多黨民主的案例》(Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America)已經于今年1月出版,書中認為不斷升級的超黨派主義已經將政治“簡化”為我們與他們,以及善與惡的二元對立。

德魯特曼表示,特朗普的言論是激化雙方長期積累憤怒的“催化劑”。特朗普入主白宮后,在競選集會上發出的激烈呼吁并未結束。相關言論聲量越來越大,也越發激烈,還在社交媒體上引發共鳴。埃默里大學(Emory University)的政治學教授阿蘭·阿布拉莫維茨說:“他從吹狗哨變成了拿著大喇叭喊”——從悄悄挖掘種族、種族和黨派的恨意,變成體育場里的大合唱。

馬里蘭大學(University of Maryland)的政府與政治副教授、《不文明協議:政治如何成為我們的身份》(Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity)一書的作者利利亞娜·梅森說,特朗普超高分貝大喇叭轟鳴的效果遠遠超出了“集會”,這種行為鼓勵了以政治為基礎的暴力,甚至變得正常化。她指出,美國“反移民”仇恨團體增加,與政客反移民言論同步就是例子。(非營利機構南方貧困法律中心表示,2014年以來,類似激進組織的數量增加了超過一倍。)“很多人警告稱會出現激進的暴力行為,主要是右翼挑起,尤其是在2020年大選前后。”梅森說,“不過美國各大城市已經有全副武裝的士兵巡邏。”10月聯邦調查局(FBI)披露,一些自稱民兵組織的厚顏無恥之徒策劃綁架了密歇根州州長格雷琴·惠特默,潛在的危險可從中一瞥。梅森表示,這些“都是2016年難以想象的”。

長長的待辦清單

盡管負面的黨派偏見導致美國社會結構撕裂,也增加了立法的挑戰性,尤其是聯邦層面“想做任何事,都得建立某種程度上的跨黨派同盟,”阿布拉莫維茨說。德魯特曼表示,實際問題甚至更嚴重。“美國制度里的根本沖突之一是,政治體制的出發點是鼓勵廣泛妥協,而政黨制度下達成妥協很難。所以,從一開始選舉和執政激勵機制就是不同的兩套制度。”政治摩擦升級只會擴大兩者之間的差別。

為了下一個世紀繼續繁榮發展,而且世界要比以往更具競爭力也更經濟,美國人必須投資自身,就像企業為了發展要自我投資一樣。這意味著為再就業計劃和關鍵基礎設施重建提供資金,具體操作起來涉及面很廣,從修復破損的道路和橋梁到建設先進的5G電信網絡均包括在內。社會保障體系的不穩定性也未減輕,需要以某種方式修正。我們要控制失控的醫保費用,控制仍然在肆虐的疫情,更要為今后的疫情做好準備。還有更棘手的問題要面對,包括應對氣候變化、刑事司法改革、制定既能夠推動產業發展和美國安全又可以維護公平感的移民政策等。到最后,我們還得想辦法幫助因疫情封鎖失業的數百萬人重返工作崗位(參見我們的選舉方案)。要做的事情可不少。

為待辦事項花錢可以說是更加艱巨的挑戰,兩黨揮金如土的領導人已經掏空了美國的錢包,而人們已經窮到快穿不起褲子。國會預算辦公室(見圖表)的數據顯示,到2023年公眾持有的聯邦債務將達到美國GDP的106%,而且屆時起紅線將繼續上升。解決問題需要創造性和雄心,意味著交戰雙方要盡棄前嫌共同努力。

這也意味著我們也要刺激美國商業增長。“如果說解決辦法就是創新,聽起來可能有點偏學術,也有點空想。”哥倫比亞大學資本主義與社會中心(Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University)的主任,2006年諾貝爾經濟學獎得主埃德蒙·菲爾普斯說。“但老實說,如果不能推動經濟發展得比過去40年或50年好,今后還能夠有多少進展真不一定。”菲爾普斯說,很高興看到企業開始積極抵制特朗普政府的關稅以及“阻礙企業開發產品所需人才”的移民政策。菲爾普斯特別希望下一屆政府能積極開展國際貿易。“國際貿易可能是美國商業部門新能源的來源。對就業、工資和其他方面都大有裨益。”他說。

微軟(Microsoft)的董事會成員、紐約私募股權公司Clayton Dubilier&Rice的合伙人桑迪·彼得森同樣對特朗普的移民政策很失望。她說:“如果我們不能齊心協力,美國的創新引擎將不復存在,創新引擎就是吸引全世界最聰明的人,創造令人驚艷的新產品。人們不再來這里學習,由于拿不到簽證,人們也無法來這工作。”彼得森曾經擔任強生(Johnson & Johnson)的全球董事長,她還表示,吸引海外人才“是長期以來推動美國經濟增長的原因,我們卻搞砸了。”

選民在這方面面臨的挑戰是,思考解決問題的最佳辦法,是再給特朗普一次機會,還是換個人重新開始。

信任和信譽

無論2021年1月20日誰上臺,都將面臨另一項緊迫任務:重建對政府機構本身的信任。過去四年里,疾病預防控制中心(CDC)、食品與藥品管理局(FDA)和司法部(Justice Department)之類過去被認為無黨派且不受政治壓力影響的機構,似乎都對白宮唯命是從,受到很多人質疑。新美國研究基金會的德魯特曼說:“之前這些機構都是中立的仲裁者,如果政治體系中人們能夠就基本的程序公平達成一致,并接受合理的反對意見,這些機構就可以保持獨立。”但身處狂熱的超黨派時代,理想的政治體系似乎已經不復存在。

馬里蘭大學的梅森表示,內訌對國家安全造成影響。她提醒說,喬治·華盛頓總統在告別演說中曾經發出警告。“如果允許派系存在,就可能自相殘殺,最終導致國家受到外部干涉;如果制造非常嚴重的黨派分歧,會使國家變弱,其他國家要攪亂美國也更容易。”梅森說。

史汀森中心(Stimson Center)是研究全球安全和其他關鍵問題的無黨派智庫,其總裁兼首席執行官布萊恩·芬萊對此表示贊同。“現在世界上的對手已經發現了美國制度的根本弱點。”芬萊說。“他們利用黨派分歧,也通過讓孩子們相信《華盛頓郵報》(Washington Post)不可信,充分利用了發現的技術弱點。我們的對手越來越聰明,現在還在攻擊選舉,就像在魚缸里點殺金魚一樣簡單。他們不需要向美國派遣武裝人員,在地下室的電腦上就能破壞。”

防御此類非同步戰爭很困難。如果沒有同盟、關系和協議就更難。美國早已簽訂多邊協議,阻止冷戰中的蘇聯擴張和侵略,限制核武器在世界各地擴散,阻止非法捕魚,當然也要出售更多的美國商品。

然而過去四年里,特朗普退出了多個重要的同盟,還威脅要“終止”美國與世界衛生組織(World Health Organization)的聯系(而且是在全球疫情泛濫期間),1948年世界衛生組織由美國倡議并協助成立。他還破壞了跨太平洋伙伴關系(TPP)貿易協定,芬雷說。

美國退出了里根總統1987年與蘇聯總理戈爾巴喬夫簽署的《中程核武器條約(INF)》(Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty),當年正是該條約推動冷戰結束。美國放棄了兩黨廣泛支持的《開放天空條約》(Open Skies Treaty),特朗普還讓美國退出了應對氣候變化的《巴黎協議》(Paris Agreement)。

對于美國的健康、繁榮和安全,以上諸多舉動更多都是自我傷害,也是選民投票時需要考慮的問題。最后簡單地說吧,我們比四年前過得更好,還是應該尋求改變了?(財富中文網)

本文登載于《財富》雜志2020年11月刊。

譯者:夏林

Forty years ago, a 69-year-old candidate for President stood on a Cleveland debate stage 15 feet from the incumbent, turned to the television audience, and asked a question that would seemingly change the race overnight: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?”

It was Oct. 28, 1980, and opinion polls until then had been suggesting a close contest between the two nominees, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, the Republican, and President Jimmy Carter, the Democrat—with the most recent of surveys splitting down the middle as to who had the edge. But the challenger’s question that evening, posed at the end of a cordial 90-minute exchange, clarified the choice in a flash. The American economy was wilting under the burden of “stagflation,” a portmanteau that roughly translated to “everything stinks”—the unemployment rate was mired at 7.5%, inflation was soaring, gasoline prices had climbed by more than a third in just the past year. Reagan, “the Great Communicator,” had framed those gloomy circumstances in a handful of words—and one week later he won the White House in a landslide, carrying 44 of the 50 states.

Four decades later, on the cusp of another presidential election, it might seem that there’s no question that’s more relevant to voters than the one Reagan asked—and a few pollsters, as you might expect, have already asked it. A September survey by the Financial Times and the Peterson Foundation found that a plurality of U.S. voters, 35%, felt better about their present financial situation, and 31% felt worse, compared with four years ago; a later poll by Gallup painted a more upbeat picture, with a clear majority of registered voters (56%) saying they were better off today. Both surveys would seem to portend good news for President Donald Trump as he faces off against former Vice President Joe Biden.

Yet here’s a surprise: The answers tell us little about how voters will actually fill out their ballots. “We’ve done a lot of research and have never really found a link between people’s own finances and how the vote turned out,” says Jeffrey Jones, who oversees all U.S. polling for Gallup, including the “better off” survey above. “People are not really self-interested when they think about how they’re going to vote, it’s really sociotropic voting: They care more about what’s going on out there as opposed to their own situation,” he says.

Far more predictive of election outcomes, says Jones, are a trio of Gallup surveys—those measuring Americans’ confidence in the economy overall, satisfaction with the way things are going in the U.S., and presidential approval—that look at the state of the nation as a whole. (In each, the President’s rating is currently underwater, and particularly so compared with previous incumbents who won reelection.)

The material question for voters, then, isn’t “Am I better off?” but rather “Are we better off?” Indeed, that was the true focus of the question Reagan framed 40 years ago, a fact that has been too often missed. As the candidate went on to prompt his TV audience in 1980:

Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was four years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe, that we’re as strong as we were four years ago?

U.S. voters today are facing additional questions that drive, perhaps, even more deeply to who we are as a nation: our shared sense of purpose, our trust in the institutions of government and society, even the way we talk and listen to one another. In every election, of course, voters will inevitably make personal choices on the basis of ideology, philosophy, or morality—as it should be. This year, though, there is one fundamental question that voters of every political bent ought to ask before they cast their ballot: Is the United States of America more or less united than it was four years ago?

Me vs. We

“Human nature really is the fundamental force that governs politics in any society at any time,” says Mike Leavitt, who was elected three times as governor of Utah and later served in President George W. Bush’s cabinet as secretary of U.S. Health and Human Services. “And this division between ‘Am I better off?’ and ‘Are we better off?’ is really the conflict between (me) individual liberty and (we) security: We give up one in order to gain the other.” Leavitt, a conservative Republican, sees the struggle between these two eternal goals—liberty and security—as a legitimate, and even necessary contest. But he is concerned with how brutal the battle has become, though he contends the vitriol has been building for far longer than in just the past four years. “We’re seeing people on both extremes who seem willing to color outside the lines, to break the covenant of democracy. And that offends us, and it scares us, because it’s not consistent with [the pact] we’ve all entered into.”

Data from the Pew Research Center shows how hardened the divisions between left and right, Democrat and Republican have become. Though the major parties are growing further apart on issues, the bigger concern is not ideological but personal. “Partisan antipathy—this is the sense that I not only disagree with the opposing party, but I take a rather negative view of the people in that party—has been growing since the mid-1990s,” says Carroll Doherty, the Pew Center’s director of political research. But in 2016, Doherty says, those negative feelings began to spike. The share of Republicans who describe Democrats as more immoral than other Americans grew from 47% in 2016 to 55% in 2019, according to Pew research. The share of Democrats who describe Republicans as immoral rose 12 percentage points, from 35% to 47%. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Republicans surveyed by Pew said Democrats are more “unpatriotic” than other Americans (23% of Democrats feel the same about Republicans), and the share in each party who view the other as more “close-minded” or “lazy” than their countrymen has climbed as well. Overwhelming majorities in both parties say the divide between them is growing, with some three-quarters of Republicans and Democrats acknowledging that they “cannot agree on basic facts” when it comes to the views of the other side. Dispiritingly, Pew found, huge percentages on both sides of the aisle (53% of Republicans and 41% of Democrats) do not want their leaders to seek “common ground” with the other party if it means giving up anything.

Doherty emphasizes that Pew’s latest study was conducted a year before the presidential election—and before the coronavirus pandemic: “While we can’t extrapolate?…?it’s possible that these negative sentiments could have grown,” he notes.

“There is this existential struggle for the soul of America in which neither side can win, and it’s all about the threat of the other side,” says political scientist Lee Drutman, a senior fellow in the political reform program at the New America foundation. “We have half of the country who’s convinced that the other half of the country—if they got power—would be illegitimate and substantially destructive.” Drutman, whose book Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America was published in January, contends that the escalating hyper-partisanship has “simplified” politics into this us-versus-them, good-versus-evil binary.

Trump’s rhetoric has been an “accelerant” to the long-simmering anger on both sides, says Drutman. The fiery invocations he unleashed at his campaign rallies didn’t end when he got to the White House. They got louder and fiercer and were echoed on social media. Says Alan Abramowitz, a professor of political science at Emory University: “He went from dog whistles to a bullhorn”—from quietly tapping into racial, ethnic, and partisan resentment to stadium-size chants.

The high-decibel roar of his MAGAphone has had an effect that goes well beyond “rallying the base,” says Lilliana Mason, associate professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, and author of the book, Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. It has encouraged and even normalized politically based violence, she says—pointing, for example, to the rise in “anti-immigrant” hate groups in the U.S., which has risen in parallel with the anti-immigration rhetoric of politicians. (The number of such groups has more than doubled since 2014, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.) “There are a lot of people warning about radical, mainly right-wing, violence specifically around the 2020 election,” says Mason, “but we’ve already seen heavily armed men walking through American cities.” To glimpse the potential danger, witness the brazen plot by members of self-styled militia groups to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, which was revealed by the FBI in October. These are things “we couldn’t even imagine in 2016,” Mason says.

A long to-do list

As much as this negative partisanship has torn America’s social fabric, it has made legislating all the more challenging—particularly at the federal level where “to get anything done, you have to be able to build coalitions that to some extent cross party lines,” says Abramowitz. Indeed, Drutman says the problem goes even deeper: “One of the fundamental conflicts in the American system is that we have political institutions that are set out to encourage broad compromise, and we have a party system that has evolved to make compromise very difficult. So we have a different set of electoral and governing incentives from the start.” The escalation in political vitriol only widens the gap between them.

To thrive over the next century—and in a world that’s more competitive, economically, than ever before—Americans must invest in the nation, just as any business needs to invest in itself in order to grow. That means funding job reskilling programs and rebuilding critical infrastructure, a sprawling mandate that spans from repairing crumbling roads and bridges to constructing advanced 5G telecom networks. The Social Security system did not get less wobbly on its own; it will need to be fixed somehow. We still have to rein in runaway health care costs, and get the still-raging pandemic under control, to say nothing of preparing for whatever outbreaks are yet to come. There are even knottier problems to contend with—climate change, criminal justice reform, crafting an immigration policy that sustains both industry, U.S. security, and a sense of fairness. And ultimately, we’ll have to find a way to put the millions of people who lost their jobs in the wake of COVID-19 shutdowns back to work (see our election package). It’s no small list of must-dos.

Paying for all of this is, if anything, a more daunting challenge: Our spendaholic leaders in both parties have already emptied America’s wallet, and we’re in hock up to our shorts. The federal debt held by the public will reach 106% of our GDP in 2023, according to the Congressional Budget Office (see chart)—and the fever line rises relentlessly from there. We’ll have to be creative and ambitious in our problem-solving—and, yes, that means the warring parties must set aside their bitterness and work together.

It also means we’ll have to hot-wire business growth in the U.S. “It sounds probably academic and otherworldly to say the solution is innovation,” says Edmund Phelps, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Economics and director of the Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University. “But quite frankly, I’m not sure how far we can progress if we don’t get the economy to be delivering better than it has been for the past 40 or 50 years.” Phelps says he is happy that companies are starting to aggressively push back on Trump administration tariffs as well as on an immigration policy that is “blocking the talents that companies need for developing new products.” Phelps is particularly keen to see the next administration embrace international trade. “It could be a source of new energy in the business sector in this country. That will be great for jobs and wage rates and everything else,” he says.

Sandi Peterson, a member of the board of directors at Microsoft and a partner at Clayton Dubilier & Rice, a New York private equity firm, is equally frustrated with Trump’s immigration policy. “If we don’t get our act together, the innovation engine of the United States—where all the smartest people in the world showed up and created all this amazing stuff—is gone,” she says. “People won’t come here to study anymore. People won’t come here to try to work anymore, because they can’t get visas,” says Peterson, who was formerly group worldwide chairman for Johnson & Johnson. Luring talent from overseas “is what has driven the economy of this country for an incredibly long time—and we just really messed it up.”

The challenge for voters, on this front, is to guess what’s the best way to fix this: Give Trump another chance or clear the slate and start over.

Trust and credibility

Whoever ends up being in charge on Jan. 20, 2021, will have another urgent task: rebuilding trust in the institutions of government itself. Over the past four years, agencies that used to be considered nonpartisan and independent from political pressure—including the CDC, FDA, and the Justice Department—have been viewed by many with skepticism and suspicion, as they have seemed to bend to White House talking points. “All of these institutions used to be neutral arbiters,” says New America’s Drutman. “And in a political system where everybody can agree on a basic procedural fairness and can accept the idea of a legitimate opposition, then these institutions can maintain their independence.” But this is one more lost treasure, it seems, in our era of fevered hyper-partisanship.

Such infighting has implications for our national security, says the University of Maryland’s Mason: President George Washington warned against this in his farewell address, she reminds us. “If you allow factions to form, you open the nation to foreign interference because we start fighting ourselves,” says Mason. “When we create this very deep partisan divide, it makes us weaker as a nation, and it makes it much easier for other nations to mess with us.”

Brian Finlay, president and CEO of the Stimson Center, a nonpartisan think tank devoted to studying global security and other critical issues, agrees. “We’re now in a world where our adversaries have identified the fundamental weaknesses of our system,” says Finlay. “They’ve exploited the divisions. They’ve exploited the technology weakness that they’ve seen by convincing our children that the Washington Post doesn’t have credibility. Our adversaries have wised up, and now they’re attacking our elections, which is like shooting fish in a barrel. They don’t need to send armed combatants to the United States. They can do it from their basement computers.”

It is hard enough to defend against such asynchronous warfare. It is harder still to do it without alliances, partnerships, and pacts. The U.S. has long entered into multilateral agreements—to stem Soviet expansion and aggression in the Cold War, limit the spread of nuclear weapons around the world, prevent illegal fishing, and naturally, sell more American goods.

But in the past four years, President Trump has pulled us away from many of these critically important alliances—even “terminating” our relationship (in the middle of a global pandemic) with the World Health Organization, an institution that the U.S. pushed for, and helped create, in 1948. He has also scuttled the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, says Finlay.

We also exited the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty that President Ronald Reagan signed with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987, and which helped to end the Cold War. We abandoned the Open Skies Treaty, which had broad bipartisan support, and Trump yanked the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

These are yet more self-inflicted wounds when it comes to America’s health, prosperity, and security—and one more consideration for voters as they head to the polls. But let’s keep it simple: Are we better off than we were four years ago, or is it time for a change??

This article appears in the November 2020 issue of Fortune.