上周早些時候,坦桑尼亞的一位小礦主成了新聞人物。他向政府出售了迄今為止發現的兩塊最大的坦桑石,并因此在一夜之間成為了百萬富翁。

政府同意以330萬美元的價格購買這兩塊透著淡藍紫光芒的寶石,并將其收藏于國家博物館。這兩塊寶石的重量分別為20.4磅和11.2磅,不過這一價格遠低于市價。對于那些希望用驚艷的藍色寶石來提升衣著氣質的名人來說,坦桑石已經成為了他們的必購珠寶。

發現了這兩塊坦桑石的礦主薩尼紐?柯延?拉伊澤今年52歲,是30個孩子(你沒聽錯,30個!)的父親,他稱自己計劃用這筆資金在東北部城市阿魯沙修建一座購物廣場,并在鄰近街區曼雅拉創辦一所學校。

然而拉伊澤的百萬富翁時光代表的不僅僅是個人的運氣,還代表著非洲政府在規范手工采礦方面所取得的罕見勝利。這個行業當前在全球雇傭了4000多萬名員工,而且涉及勞工剝削、人權侵犯和環境破壞問題。就坦桑石而言,坦桑尼亞一直在使用市場機制來引導難以滿足的供需關系,以打造一個可持續性更好,破壞性有望更小的行業。

坦桑石是全球最稀有的礦石之一,全球僅有一小塊地區有儲量,也就是坦桑尼亞北部梅樂拉尼山區5平方英里的地區,它是地殼板塊在5.85億年前激烈碰撞的產物,此次碰撞亦催生了乞力馬扎羅火山。這塊區域首先由黃金勘探公司于1967年發現,鉆石公司戴比爾斯第二年便將寶石帶進了珠寶使用市場。然而在最近10年,其受歡迎程度飆升,也在梅樂拉尼山區掀起了采礦熱。

在百慕大注冊的公司TanzaniteOne Ltd.在這里經營著一家大型商業礦場。經官方許可,該公司與坦桑尼亞國有采礦公司合作,共同經營這片區域。該公司曾在倫敦上市,但目前已經私有化。

但數百家小規模未經許可的礦場如雨后春筍般出現在這一地區,也為該地區帶來了眾多困擾其他手工礦區的類似問題:不安全的工作環境和勞動力剝削。

由于這些小礦主都沒有拿到許可,礦主不得不通過非法渠道來銷售那些開采出來的未經切割的寶石,因而也催生了涵蓋走私網絡,高利貸和有組織犯罪的地下經濟,同時還助長了政府腐敗,因為有人對官員們行賄,希望他們對此視而不見。與此同時,坦桑尼亞本身也損失了來自于許可費和礦石開采權的收入。政府估計,2017年走私出境的坦桑石比例高達40%。

政府間礦業、礦產、金屬和可持續發展論壇(IGF)的2017年報告稱,這類問題對手工采礦來說十分常見。該論壇在報告中寫道:“環境、健康和安全舉措非常匱乏。例如,爆破和鉆探帶來的塵土和超細顆粒物會導致呼吸道疾病。”

小規模金礦開采會使用水銀來分離黃金與其他金屬,因此在這一方面的問題尤為嚴重。IGF稱,事實上,手工采礦是全球最大的水銀污染源,估計每年有1400噸的水銀被釋放到環境中。報告還指出:“暴露于水銀污染環境會帶來嚴重的健康問題,包括不可逆轉的大腦損傷。水銀還難以控制,即便是非常小的劑量也具有毒性,它可以通過空氣或水遠距離傳播,讓土壤和水道帶有毒性,并最終進入食物鏈。在非洲撒哈拉以南地區,這類風險大多由女性承擔。”

IGF稱,然而,小規模采礦對于眾多高價值礦石生產來說異常重要:全球20%的黃金供應、80%的藍寶石和20%的鉆石都是采用這種方式。電子組件的重要金屬亦通過小規模礦場開采,包括全球25%的錫和26%的鈦供應,這些都是電腦芯片和智能手機所使用的金屬。

就坦桑石而言,坦桑尼亞政府一開始實際上是在嘗試回避這個問題。因為坦桑石在這個區域分布的過于集中,2017年,坦桑尼亞總統約翰?馬古富利決定在整個采礦區域建一道圍欄,但圍欄對區隔供需來說向來都沒有多大的作用,不過確實減少了非法開采的坦桑石數量,卻也推高了坦桑石的價格以及走私的利潤。

因此,政府在2019年還實行了一項新政策。它決定擴大坦桑石以及黃金和其他礦石的合法市場,并向小規模礦主提供授權,設立了正式的政府礦石交易中心,從而讓他們以公允的價格銷售其礦品。設立的28家官方交易中心均靠近礦場,這樣這些小礦場便可以直接銷售其礦品,而無需借助那些時常不擇手段的中間商來將其礦品帶到更大城市的市場。這一現象一直都是坦桑石交易過程中腐敗的一個來源。

得益于市場的設立,政府能夠高效地對采礦生產征稅。此外,政府調整了礦主的應付稅率,按照銷售額的7%征收許可費用。此前,礦主們得支付一大堆稅費:5%的預扣稅、礦產銷售18%的增值稅和7.3%的檢查費,以及最高0.3%的政府服務稅。稅務與經濟政策研究所的高級經濟師馬修?薩洛蒙對行業刊物《采礦技術》(Mining Technology)說,新稅收構架更加扁平,“其設計十分有利于打擊走私,更低的稅率可以激勵小規模礦主通過中心進行交易。”

新誕生的坦桑石百萬富翁拉伊澤向我們展示,坦桑尼亞實現非正規采礦經濟正規化的舉措開始奏效。政府之所以能夠購買其巨大的坦桑石樣本,是因為他將其帶到了政府交易中心。在過去,世人可能根本無法知道還存在這類巨型寶石,因為它們可能會被偷運至海外。

坦桑尼亞的礦產部部長多托?比特克在上周慶祝拉伊澤發現的活動上說:“過去,小礦主會走私坦桑石,但如今這一情況發生了變化,他們會遵循流程,并向政府交納稅費。”

在看到坦桑石和黃金采礦獲得初步成功之后,坦桑尼亞希望將這一制度拓展至其他礦石品種,而且該國可能會為其他以采礦為主要經濟來源的國家樹立一個很好的榜樣。(財富中文網)

譯者:Feb

上周早些時候,坦桑尼亞的一位小礦主成了新聞人物。他向政府出售了迄今為止發現的兩塊最大的坦桑石,并因此在一夜之間成為了百萬富翁。

政府同意以330萬美元的價格購買這兩塊透著淡藍紫光芒的寶石,并將其收藏于國家博物館。這兩塊寶石的重量分別為20.4磅和11.2磅,不過這一價格遠低于市價。對于那些希望用驚艷的藍色寶石來提升衣著氣質的名人來說,坦桑石已經成為了他們的必購珠寶。

發現了這兩塊坦桑石的礦主薩尼紐?柯延?拉伊澤今年52歲,是30個孩子(你沒聽錯,30個!)的父親,他稱自己計劃用這筆資金在東北部城市阿魯沙修建一座購物廣場,并在鄰近街區曼雅拉創辦一所學校。

然而拉伊澤的百萬富翁時光代表的不僅僅是個人的運氣,還代表著非洲政府在規范手工采礦方面所取得的罕見勝利。這個行業當前在全球雇傭了4000多萬名員工,而且涉及勞工剝削、人權侵犯和環境破壞問題。就坦桑石而言,坦桑尼亞一直在使用市場機制來引導難以滿足的供需關系,以打造一個可持續性更好,破壞性有望更小的行業。

坦桑石是全球最稀有的礦石之一,全球僅有一小塊地區有儲量,也就是坦桑尼亞北部梅樂拉尼山區5平方英里的地區,它是地殼板塊在5.85億年前激烈碰撞的產物,此次碰撞亦催生了乞力馬扎羅火山。這塊區域首先由黃金勘探公司于1967年發現,鉆石公司戴比爾斯第二年便將寶石帶進了珠寶使用市場。然而在最近10年,其受歡迎程度飆升,也在梅樂拉尼山區掀起了采礦熱。

在百慕大注冊的公司TanzaniteOne Ltd.在這里經營著一家大型商業礦場。經官方許可,該公司與坦桑尼亞國有采礦公司合作,共同經營這片區域。該公司曾在倫敦上市,但目前已經私有化。

但數百家小規模未經許可的礦場如雨后春筍般出現在這一地區,也為該地區帶來了眾多困擾其他手工礦區的類似問題:不安全的工作環境和勞動力剝削。

由于這些小礦主都沒有拿到許可,礦主不得不通過非法渠道來銷售那些開采出來的未經切割的寶石,因而也催生了涵蓋走私網絡,高利貸和有組織犯罪的地下經濟,同時還助長了政府腐敗,因為有人對官員們行賄,希望他們對此視而不見。與此同時,坦桑尼亞本身也損失了來自于許可費和礦石開采權的收入。政府估計,2017年走私出境的坦桑石比例高達40%。

政府間礦業、礦產、金屬和可持續發展論壇(IGF)的2017年報告稱,這類問題對手工采礦來說十分常見。該論壇在報告中寫道:“環境、健康和安全舉措非常匱乏。例如,爆破和鉆探帶來的塵土和超細顆粒物會導致呼吸道疾病。”

小規模金礦開采會使用水銀來分離黃金與其他金屬,因此在這一方面的問題尤為嚴重。IGF稱,事實上,手工采礦是全球最大的水銀污染源,估計每年有1400噸的水銀被釋放到環境中。報告還指出:“暴露于水銀污染環境會帶來嚴重的健康問題,包括不可逆轉的大腦損傷。水銀還難以控制,即便是非常小的劑量也具有毒性,它可以通過空氣或水遠距離傳播,讓土壤和水道帶有毒性,并最終進入食物鏈。在非洲撒哈拉以南地區,這類風險大多由女性承擔。”

IGF稱,然而,小規模采礦對于眾多高價值礦石生產來說異常重要:全球20%的黃金供應、80%的藍寶石和20%的鉆石都是采用這種方式。電子組件的重要金屬亦通過小規模礦場開采,包括全球25%的錫和26%的鈦供應,這些都是電腦芯片和智能手機所使用的金屬。

就坦桑石而言,坦桑尼亞政府一開始實際上是在嘗試回避這個問題。因為坦桑石在這個區域分布的過于集中,2017年,坦桑尼亞總統約翰?馬古富利決定在整個采礦區域建一道圍欄,但圍欄對區隔供需來說向來都沒有多大的作用,不過確實減少了非法開采的坦桑石數量,卻也推高了坦桑石的價格以及走私的利潤。

因此,政府在2019年還實行了一項新政策。它決定擴大坦桑石以及黃金和其他礦石的合法市場,并向小規模礦主提供授權,設立了正式的政府礦石交易中心,從而讓他們以公允的價格銷售其礦品。設立的28家官方交易中心均靠近礦場,這樣這些小礦場便可以直接銷售其礦品,而無需借助那些時常不擇手段的中間商來將其礦品帶到更大城市的市場。這一現象一直都是坦桑石交易過程中腐敗的一個來源。

得益于市場的設立,政府能夠高效地對采礦生產征稅。此外,政府調整了礦主的應付稅率,按照銷售額的7%征收許可費用。此前,礦主們得支付一大堆稅費:5%的預扣稅、礦產銷售18%的增值稅和7.3%的檢查費,以及最高0.3%的政府服務稅。稅務與經濟政策研究所的高級經濟師馬修?薩洛蒙對行業刊物《采礦技術》(Mining Technology)說,新稅收構架更加扁平,“其設計十分有利于打擊走私,更低的稅率可以激勵小規模礦主通過中心進行交易。”

新誕生的坦桑石百萬富翁拉伊澤向我們展示,坦桑尼亞實現非正規采礦經濟正規化的舉措開始奏效。政府之所以能夠購買其巨大的坦桑石樣本,是因為他將其帶到了政府交易中心。在過去,世人可能根本無法知道還存在這類巨型寶石,因為它們可能會被偷運至海外。

坦桑尼亞的礦產部部長多托?比特克在上周慶祝拉伊澤發現的活動上說:“過去,小礦主會走私坦桑石,但如今這一情況發生了變化,他們會遵循流程,并向政府交納稅費。”

在看到坦桑石和黃金采礦獲得初步成功之后,坦桑尼亞希望將這一制度拓展至其他礦石品種,而且該國可能會為其他以采礦為主要經濟來源的國家樹立一個很好的榜樣。(財富中文網)

譯者:Feb

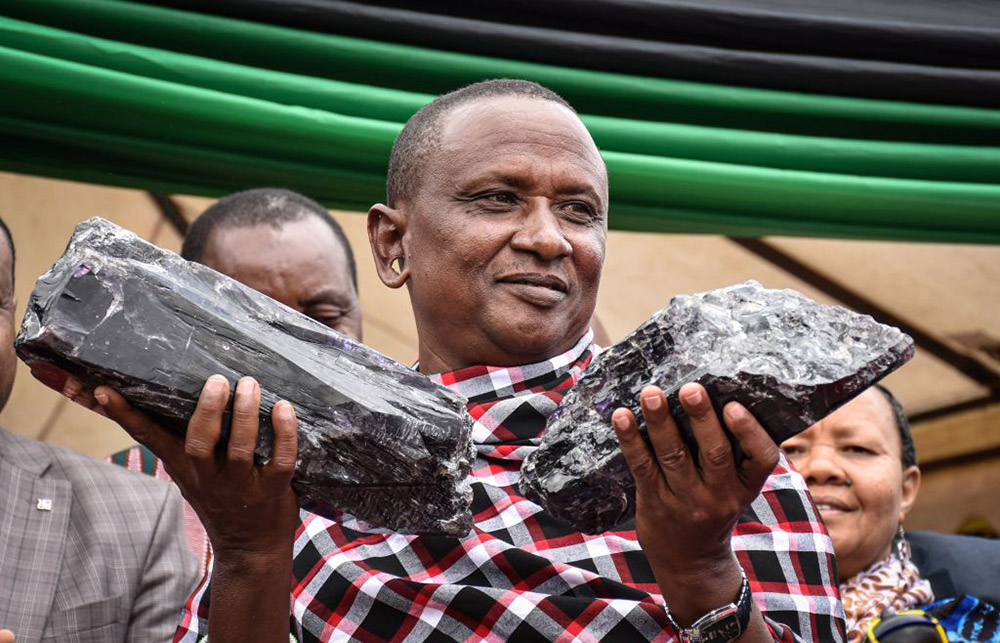

Earlier last week, a small-scale miner in Tanzania made headlines around the world when he became a multimillionaire overnight after selling to the government two of the largest tanzanite rocks ever unearthed.

The government agreed to buy the brilliant violet-blue-tinged precious stones, which weighed in at 20.4 and 11.2 pounds respectively, for $3.3 million—which is well below their actual market value—and put them in the country’s museum. Tanzanite has become something of a must-have jewel for celebrities looking to spice up their outfit with a striking blue gem.

Saniniu Kuryan Laizer, the 52-year-old miner and father of 30—yes, 30!—who discovered the tanzanite samples, said he planned to invest the money in a shopping mall in the northeastern city of Arusha and to build a local school in the neighboring district of Manyara.

But Laizer’s millionaire moment represents more than just an amazing stroke of luck for one man. It represents a rare victory for an African government in being able to regulate artisanal mining—a practice that employs more than 40 million people around the globe and is implicated in exploitative labor practices, human rights abuses, and environmental degradation. With tanzanite, Tanzania has managed to use market mechanisms to channel the insatiable forces of demand and supply to create a more sustainable and possibly less damaging industry.

Tanzanite is one of the world’s rarest minerals. It is found in only one tiny patch of the globe, just five square miles in size, in the Mererani Hills of northern Tanzania, the legacy of a violent clash of tectonic plates 585 million years ago that would also spawn the volcano that is today Mount Kilimanjaro. Only first discovered by a gold prospector in 1967, diamond company De Beers brought the gem to market for use in jewelry the following year. But in the past decade its popularity has soared, setting off a mining boom in the Merarani Hills.

One large-scale commercial mine, operated by a Bermuda-registered company called TanzaniteOne Ltd., has an official concession to operate in the area in partnership with the State Mining Company of Tanzania. It was once publicly listed in London but is now in private hands.

But hundreds of small-scale, unlicensed pit mines have sprung up all over the area—bringing with them many of the same problems that have plagued artisanal mining of other minerals elsewhere: unsafe working conditions and exploitative labor practices.

Because none of the miners were licensed, miners had to sell the uncut gemstones they excavated illicitly, giving rise to an underground economy of smuggling networks, loan sharks, and organized crime. It also spurred government corruption as officials were paid to look the other way. Meanwhile, Tanzania itself lost out on revenues it could have derived from royalty fees and mineral rights. The government estimated in 2017 that 40% of tanzanite was being smuggled out of the country.

These sorts of problems are common to artisanal mining, according to a 2017 report of the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF). “Environmental and health and safety practices tend to be very poor. For example, dust and fine particles resulting from blasting and drilling cause respiratory illnesses,” the IGF wrote.

Small-scale gold mining, which uses mercury to separate gold from other metals, is especially problematic. In fact, artisanal mining is the largest global source of mercury pollution—estimated at 1,400 tonnes of mercury released into the environment each year, the IGF says. “Exposure to mercury can have serious health impacts, including irreversible brain damage,” the report continues. “Mercury is also difficult to contain and can be toxic at even very small doses. It can be transported long distances by air or water, poisoning the soil and waterways, and eventually making its way into the food chain. In sub-Saharan Africa, most of these risks are borne by women.”

And yet small-scale mining is key to the production of many valuable minerals: 20% of the world’s gold supply, 80% of sapphires, and 20% of diamonds are mined this way, according to the IGF. Key metals for electronic components are also extracted by small-scale mines: 25% of the world’s tin and 26% of the supply of tantalum, which is used in computer chips and smartphones.

In the case of tanzanite, the Tanzanian government first tried to wall off the problem—literally. Because the area where tanzanite is found is concentrated so densely, in 2017, Tanzania’s President John Magufuli decided to build a fence around the entire mining region. But fences are never very good at separating supply from demand. The fence did reduce the amount of tanzanite being mined illicitly, but it also drove prices higher and made smuggling more lucrative.

So, in 2019, the government also instituted a new policy. It decided to expand the legitimate market for tanzanite—as well as gold and other minerals. It began licensing small-scale miners and set up official government mineral trading centers where they could sell their production at a fair prices. The 28 official trading hubs established so far are all close to mining sites, so that small miners could sell their production directly, without having to rely on sometimes unscrupulous middlemen to take the minerals to markets in bigger cities, which had been a source of corruption in the trade.

The markets also allow the governments to efficiently tax mining production. Plus, the government changed the tax rate miners have to pay, reducing it to a 7% royalty rate on sales. Previously miners paid a litany of taxes and fees: 5% withholding tax, plus 18% value-added tax on mineral sales, plus 7.3% inspection fees, and a 0.3% government service levy on top. The new, flatter tax structure is “well designed to curb smuggling,” Matthew Salomon, the senior economist for the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, told trade publication Mining Technology. “The lower tax rate should provide incentives for small-scale miners to transact through the hub.”

That newly minted tanzanite millionaire, Laizer, shows that Tanzania’s efforts to formalize the informal mining economy is starting to work. He’s one of the small-scale miners recently licensed by the government. The government was able to purchase his huge tanzanite specimens because Laizer brought it to a government trading hub. In the past, it might never have even known the giant gemstones existed—they would likely have been spirited out of the country.

"We are now moving from a situation where the small miners were smuggling tanzanite, and now they are following the procedures and paying government taxes and royalties,” Tanzanian mining minister Dotto Biteko said at an event last week celebrating Laizier’s find.

Having shown initial success with tanzanite and gold, Tanzania is hoping to expand the system to other minerals too, and it could prove to be a model for other mining-dependent economies throughout Africa.