|

天一冷,維多利亞的iPhone 6指紋識別功能就不太好使。約翰的6s電池越來越不耐用,他總得跪著或坐在機場地上給手機充電,簡直煩透。幾個月前,亨利發(fā)現(xiàn)在iPhone上輸入“I”時,有時會突然變成“A?”南希年級大了,最煩iPad升級“新格式”時不提供使用指導。亞當年紀小,他看不上蘋果,選擇了谷歌的Pixel 2 XL,因為更喜歡谷歌的設計和應用。托尼則認為iTunes不再是井井有條的音樂庫,吵吵鬧鬧的,成了蘋果音樂推廣的工具,所以他改為用Spotify和Pandora。 我家里五口人,家里18臺蘋果設備,每天充電或連接其他設備要用二十多根線。其中有六根線嚴重磨損,只好用膠布裹著,感覺線材外面薄薄一層橡膠雖然顏值高,但不太能堅持每日密集使用。更糟糕的是,找線非常頭疼,USB接口、Lightning接口、Thunderbolt接口還有USB-C接口對應的線都不一樣而且互不兼容,每次“升級”后買的轉接頭又早都弄丟了,有可能塞在哪個沙發(fā)墊子后面,如果真去翻遍沒準能順便找到安雅小小的iPod Shuffle,還有塔爾弄碎的iPhone 6原裝耳機。 |

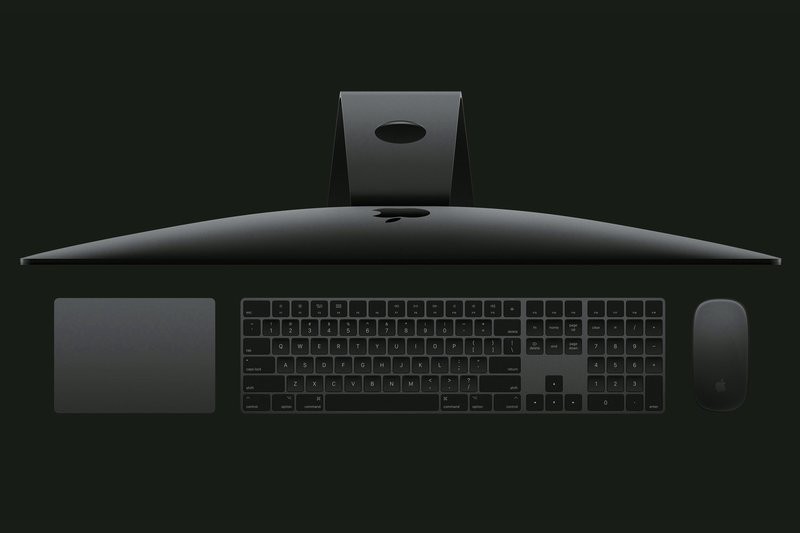

The Touch ID on Victoria’s iPhone 6 doesn’t work well in the winter cold. John is tired of kneeling or sitting on airport floors to plug in his 6s, whose battery seems incapable of lasting through the day. A few months ago, Henry noticed that when he’d type an “I” into his iPhone, “A?” would sometimes show up on his screen. Nancy, who’s older, hates that Apple (AAPL, +0.03%) never provides instructions after upgrading her iPad to “new formatting.” Adam, who’s younger, has ditched Apple for Google’s Pixel 2 XL, because he prefers the design and uses Google apps. Tony, who thinks iTunes has gone from being a well-organized music library to a disorganized marketing vehicle for Apple ?Music, has subscribed to Spotify and Pandora. The five people in my home use two dozen cables to power and connect 18 Apple devices. Six are frayed and wrapped in duct tape—their thin, rubberized, and attractive-till-it-breaks covering doesn’t seem designed for the heavy use these cables obviously get. Worse yet, hunting one down takes ages, because the USB, Lightning, Thunderbolt, and USB-C cables are incompatible in a variety of ways, and the little adapters I purchased after each “upgrade” have been lost long ago, probably behind some couch cushion that’s also hiding Anya’s too-tiny iPod Shuffle and the earbuds that came with the iPhone 6 that Tal shattered. |

|

如果你的朋友和家人也遇到過這些問題,可能已經(jīng)聽過不少對蘋果設計的吐槽。實際上,現(xiàn)在全球各地都流行吐槽蘋果設計讓人不滿意之處。只要上谷歌輸入“蘋果設計真爛”,就能發(fā)現(xiàn)無數(shù)抱怨,揭穿了表面華麗卻很不實用的設計:蘋果手表越用越遲鈍;最新款鍵盤用著讓人煩而且很容易壞;電容筆特別容易弄丟;自從iPhone后置鏡頭凸出表面就飽受詬病,iPhone X屏幕上冒出一截“眉毛”后罵聲更多。嘲弄的標題頻繁見諸報章:“蘋果的偉大設計之謎”(《亞特蘭大》月刊),“蘋果無懈可擊的設計到處出了什么問題?”(《The Verge》),還有“蘋果真的不會設計”(The Outline網(wǎng)站),每次都引發(fā)網(wǎng)友議論紛紛。 以往很受尊敬的開發(fā)者和設計師受到很多指責。Tumblr聯(lián)合創(chuàng)始人馬可·埃蒙特向來欣賞蘋果大部分設計,但也表示“喬布斯去世后,蘋果的設計風格有些失衡。仿佛過于強調美感,不太注重實用。”曾在蘋果設計團隊工作的唐恩·諾曼(1993年-1996年)如今在加州大學圣地亞哥分校負責設計實驗室,他認為蘋果已經(jīng)放棄用戶中心的設計理念。“他們?yōu)榱俗非竺栏袪奚撕唵我子茫彼硎尽? 當然,也不是所有人都同意。在iOS平臺開發(fā)最新應用的愛爾蘭籍開發(fā)者史蒂夫·桑頓-史密斯表示,“我對蘋果的歷史非常了解,現(xiàn)在設計風格轉變(跟史蒂夫·喬布斯離世)并無關系,蘋果用戶應該也不會覺得陌生。即便喬布斯在的時候,對USB線和iTunes的吐槽也有很多年,我還收藏著磨壞的30針接口線呢。” “我認為蘋果的設計風格一如既往,”蘋果產品博主負責人約翰·格魯伯表示。“看看最近的產品就知道了。2016年的AirPods,2017年的iPhone X,都是帶有強烈蘋果設計風格的產品。兩款產品里都有強烈的‘真是好用’的氣息。” 當然了,設計具有很強的主觀性。對于iPhone X(X是羅馬數(shù)字里的10),兩位理性的用戶很可能有截然相反的觀點,而且關于蘋果產品比起喬布斯時代是更好還是更差,人們也很容易吵起來。要說沒那么主觀的因素,可能就是簡單的事實:蘋果是家設計公司。蘋果的未來并不取決于是否引領人工智能、虛擬現(xiàn)實或其他技術的潮流。蘋果的未來在于設計。 多年來,蘋果比其他公司強的一點在于,清楚認識到消費者真正需要怎樣的技術,然后將各元素組合成為易用的產品,由此吸引了全球數(shù)十億用戶。雖然過程中也犯過幾次錯,但還是遠超其他技術同行,而且長期在大眾市場保持成功。目前全球用戶在使用10多億部蘋果產品,有些疏漏也在所難免。 但近來對蘋果設計的吐槽確實越來越嚴重。而且這種吐槽不能輕易忽略,因為如果蘋果設計真的出現(xiàn)問題,就意味著全球市值最高的公司遇到了大麻煩。 蘋果設計的核心理念一直是保持簡潔流暢且易用,同時盡可能增加更多功能。蘋果設計最強大,沒錯,最強大的一點在于,總能準確把握何時、怎樣以及加入哪些最新技術。批評者稱,蘋果選擇的眼光遠不如以往。 拿2017年11月發(fā)布的iPhone X為例,蘋果在電視廣告之類推廣時強調屏幕無邊框和按鈕,圓潤的四角縈繞著紅色和紫色的光芒。10月我為《Smithsonian》雜志采訪喬尼·伊夫(蘋果拒絕允許伊夫就本文接受采訪)時,他表示新款屏幕體現(xiàn)了蘋果設計的精髓。“設計團隊一直努力做減法,”他表示,“我們不是想削弱實物的感覺,只是不想讓外物阻礙用戶與技術順暢交互。”看上去X的屏幕一片空,顯得很優(yōu)雅,這也是蘋果一直以來的追求,即消除用戶與數(shù)字世界、娛樂和服務之間的隔閡。 X的屏幕之所以能如此簡單,是因為蘋果徹底取消了實體Home鍵。之前歷代iPhone上,屏幕下方都有個實體的圓形小凹面,一按就能返回主屏幕,打開想用的軟件。按下Home鍵,就能回到主屏幕。概念很簡單,但唐恩·諾曼認為取消Home鍵沒什么道理。“為了突出屏幕的簡潔,增加了用戶使用的難度,”諾曼說。“而且取消Home鍵后增加了更難理解的手勢操作。” 現(xiàn)在如果想在iPhone X上回到主屏幕,就得從屏幕下方向上掃。之前的iPhone 7里從下方向上掃會召出控制中心,手電、計時器、照相等常用功能都在里面。但現(xiàn)在要在iPhone X里進控制中心就得從右上往左下斜掃。要想關閉打開的應用,就得從屏幕下方往上掃,然后長按屏幕。實際用起來倒是挺自然,我11歲的女兒安雅長期沉迷iPad,她告訴我說,“所有的手機都應該這么操作!”但并不是所有人都能用慣。感恩節(jié)時我向岳母南希解釋多點觸控的用法。“算了!”她氣洶洶地說。“我學不會!” 蘋果老款產品中也能體現(xiàn)出追求功能復雜和保持美感的矛盾,尤其是臺式機和筆記本電腦。許多重度用戶抱怨多年后,2016年末蘋果終于發(fā)布了最新款MacBook Pro,鍵盤上方明亮的條形觸摸屏取代了原先的F系列功能鍵,可根據(jù)當前使用的軟件提供相應的快捷鍵。該功能叫Touch Bar,因為可以用手指操控,看上去視覺效果相當好,也體現(xiàn)出相當精妙的工程技術。 但如果功能使用過程太復雜,添加功能就失去了本意。博主格魯伯向來是堅定的果粉,熱愛蘋果所有產品,但他表示,“對我來說,Touch Bar完全違背了史蒂夫·喬布斯的理念,即設計不僅關于外表,更重要是如何使用。”最初版本中,Touch Bar就像個半成品,只是將iPad部分觸摸功能移植到筆記本電腦上。“蘋果是不是一心迷著追求工程美學了,”埃蒙特說。“開發(fā)圈里我認識的很多人都用這款電腦,但沒人喜歡Touch Bar。” 其實蘋果設計團隊大部分已共事多年,不太可能“迷著追求工程美學”。問題在于用戶期望蘋果每次都做出完美選擇,如果做不到就很失望。“Siri風格變幽默后,我不少朋友很生氣,”格魯伯表示,Siri是蘋果系統(tǒng)里的語音助手,很多人認為遠遠比不上亞馬遜的Alexa和谷歌的谷歌語音助手。“如果想做飯的時候讓Siri停止計時器,Siri不會老實說一句,‘好的,停止計時器,’通常她會開玩笑地說:‘好的,計時器會停止,要是雞蛋煎糊了可別怪我哦!’這讓用戶很煩。我覺得幽默路子走偏了。設計師原本想添加人性元素,但做得太生硬。感覺Siri抓不住人們的意思,尤其是誤會用戶的問題還自作幽默的時候。” Siri轉向幽默跟iPhone X加不加Home鍵都是設計決策。這也是幾乎當前所有產品開發(fā)公司共同面臨的問題之一,因為現(xiàn)在流行萬物互聯(lián),從玩具、洗碗機、火車引擎、酒窖到鑰匙扣之類都在智能化。如果蘋果做不好Siri,人們就忍不住要擔心蘋果的未來。技術的世界越發(fā)復雜,現(xiàn)在很多人開始認為新產品里亞馬遜的Echo真正實現(xiàn)了簡化生活。這勢頭可不太妙,是吧? 對很多批評蘋果的人士來說,故事就此結束。Siri不夠智能,Touch Bar難用,操作系統(tǒng)雖然華麗但讓人容易犯迷糊,用得順手的Home鍵又沒了……還可以列舉一大堆。總之,蘋果很不完美。很有道理。 但有件事別忘了:回溯歷史你會發(fā)現(xiàn),蘋果歷次選擇總會引發(fā)擔心,經(jīng)常看起來可能失敗,即便是喬布斯重返蘋果之后那些年月也一樣。1998年蘋果推出外形漂亮,胖嘟嘟青藍色的iMac,但功能很有限,鼠標很不穩(wěn)定,CD插槽沒幾個用戶真正能用上。2000年推出經(jīng)典的Power Mac G4 Cube,由于外形設計太贊還被收入現(xiàn)代藝術博物館,功能仍然比較簡單,沒法滿足重度用戶的需求。2001年第一代iPad誕生,但并沒有立刻火起來,因為滾輪不太靈活,而且只能連接Mac電腦使用,當時Mac還只占全世界個人電腦銷量的2.6%。2005年,蘋果首次涉足手機業(yè)務!當時蘋果跟摩托羅拉合作開發(fā)了一款兼具音樂播放和手機功能的混搭設備,取名叫Rokr。2007年iPhone出現(xiàn),只有少數(shù)幾款應用,連接性能也不好。2011年發(fā)售iPad,我姐夫馬克跟我說,“想不出誰會用買這東西用。”(后來他買了四個。) 事實上,蘋果產品很少剛出現(xiàn)就完美。往往是新品推出之后花很長時間完善設計,將設計上的“失誤”變?yōu)槌晒Α? 蘋果手表是2015年發(fā)售的。推出之前外界預期很高:這會成為喬布斯去世后首款革新性產品么?“蘋果的iPod之類產品實在太棒了,導致我們開始懷疑生活中其他物品是不是設計有問題,”紐約視覺藝術學院產品設計項目系主任艾倫·喬奇諾夫表示。“為什么溫度調節(jié)器做不到蘋果那么漂亮?”也許手表設計進化到iPhone水平的時候到了。 大家或許還記得,發(fā)售后媒體很失望。說失望都算客氣的。當時的批評包括,手表用戶界面一團亂,層層疊疊混亂難用。只看手表還挺漂亮,但如果戴著去健身房就會發(fā)現(xiàn),跟Fitbit之類市場上流行的健身追蹤器相比一點也不方便。只有iPhone在身邊手表才能彈出提示信息,必須輕抬手腕才能看時間,我覺得還沒斯沃琪手表好用,人家還比蘋果手表便宜近300美元。 |

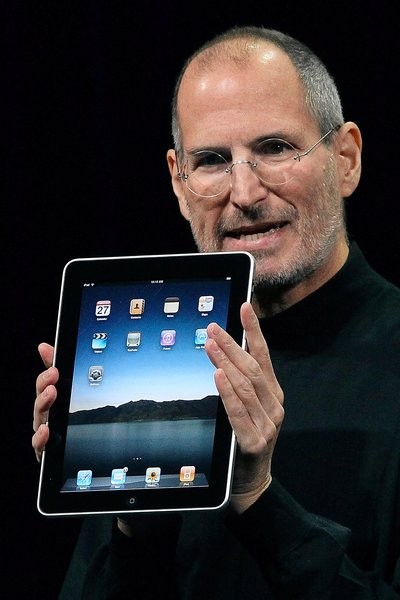

If your friends and family are anything like my friends and family, you’ve been hearing a lot of complaints about Apple design recently. In fact, enumerating the ways Apple design fails consumers seems to have become an international pastime. Google “Apple design sucks,” and you’ll find a never-ending litany of the seemingly infinite ways that this ostensible paragon of design excellence misses the mark: The Watch isn’t out-of-the-box intuitive; the latest keyboards are annoying and fragile; Apple Pencils are easy to lose; the iPhone has been flawed ever since Apple introduced that camera lens that juts out on the back, and things have gotten worse with the “notch” on the screen of the iPhone X. Belittling headlines abound: “The Myth of Apple’s Great Design” (The Atlantic), “What Happened to Apple’s Faultless Design?” (The Verge), and “Apple Is Really Bad at Design” (The Outline), a recent screed that generated a lot of online chatter. Highly respected developers and designers have weighed in with damning criticism. Tumblr cofounder Marco Arment admires most Apple design, but says, “Apple designs in the post-Steve era have been a little off-balance. The balance seems too much on the aesthetic, and too little on the functional.” Don Norman, a former member of the Apple design team (1993–1996) who now heads the Design Lab at the University of California, San Diego, beats the drum that Apple has abandoned user-centered design principles. “They have sacrificed understandability for aesthetic beauty,” he says. Not everyone agrees, of course. Says Steve Troughton-Smith, an Irish developer of sleek iOS apps, “I have enough historical context to understand that these things have no relation to [Steve Jobs’ departure], and are not a new aspect of being an Apple user. Things like USB cables and iTunes were bad for many years under Jobs too, and I have a collection of frayed Firewire-to-30-pin cables to remind me of that.” “I would argue that Apple design is as good as ever,” says John Gruber, the dean of Apple bloggers. “Look at the most recent products. AirPods last year, and the iPhone X this year, are quintessential Apple products. There’s a huge ‘it just works’ factor to them both.” Design is subjective, of course. It’s entirely possible for two intelligent people to have diametrically opposite views on the iPhone X (“ten” in Roman numeral form), and it’s entirely possible for intelligent people to argue about whether Apple’s product design is better or worse than when Steve Jobs was CEO. What’s not subjective, however, is this simple business fact: Apple is a design company. Its future doesn’t rest on being first in artificial intelligence, virtual reality, or any other technology. Its future rests on design. For years now, Apple has done a better job than any other company of discerning what technologies will really matter to customers, and assembling those into remarkably intuitive products that appeal to millions and millions of people around the world. No tech company has ever had such a long and consistent run of mass-market success, even if there have been a few clunkers along the way. With perhaps a billion or more Apple products in active use, there are bound to be some that miss the mark. But the volume of grumbling about Apple design has been loud of late. And the chatter can’t simply be dismissed—because if Apple design is truly in trouble, then the world’s most valuable company is in trouble. A central design tension at Apple has always been keeping its products clean, streamlined and easy-to-use while adding more, and more powerful, features. The best Apple designs—the best product designs, period—navigate this tension by making astute choices about when, what, and how to incorporate new technologies. Critics argue that Apple is making more poor choices than in the past. Take the iPhone X, which was released in November. In its marketing of the X, Apple makes much of the beauty of a screen without bezels or buttons—in television ads, for instance, great swirls of red and purple color caress the rounded corners of the screen. When I interviewed Jony Ive in October for Smithsonian magazine (Apple declined to make Ive available for this story), he described the screen as an embodiment of a key Apple design principle. “As a design team, we’re trying to get the object out of the way,” he said. “We’re not denying that it’s material, but we want to get to that point where it is in no way an impediment to the technology that you care about.” The spare and elegant screen on the X is as close as Apple has come to erasing the barrier between you and the world of digital data, entertainment, and services. One reason the X has such a simple screen is that Apple chose to eliminate the Home button. The Home button is that small concave circle at the bottom of all prior iPhones that you press at any time to get back to your Home screen, where you can access all of your most important apps. Press the Home button, return to the Home screen. It was a simple concept, and, if you ask Don Norman, there was no good reason to abandon it. “They made it harder for people by their emphasis on the utter simplicity of the screen,” says Norman. “They took away the Home button, and they added even more mysterious gestures.” In fact, to conjure the Home screen on my iPhone X, I swipe up from the bottom of the screen. On my old iPhone 7, that same gesture took me to the Control Center, with its icons for my flashlight, timer, camera, and other basic features. But to get to the Control Center on my X, I swipe down in a diagonal line from the top right. And if I want to see and close all those apps I’ve had open for some time, I swipe up from the bottom, but press down on the screen at the end of the swipe. In practice, this all comes quite naturally: My 11-year-old, Anya, who has spent more time than makes sense with an iPad, told me, “This is the way all phones should work!” But it’s not for everyone. I tried to explain multitouch gestures to my mother-in-law, Nancy, over Thanksgiving. “That’s it!” she snapped. “I’m done!” The tension between complexity and aesthetic streamlining is especially evident in Apple’s oldest product lines—its desktop and laptop computers. After years of complaints from heavy users who rely on its most powerful computers, Apple released a new MacBook Pro laptop in late 2016, with a brightly lit digital touch screen strip that replaced the F keys at the top of the keyboard. The strip changes as you work, offering up shortcuts to features that might be relevant to whatever is up on your screen. Called the Touch Bar, because you manipulate it with your finger, the strip looks great and is a marvelous feat of engineering. But adding functions isn’t really an addition if the process of using those functions is confusing. “To me,” says blogger Gruber, usually a reliable supporter of all things Apple, “the Touch Bar is the ultimate violation of that Steve Jobs axiom that design isn’t about how something looks, but about how it works.” In this first iteration, the Touch Bar seems like an unsuccessful, half-baked effort to bring some of the iPad’s touch control to Apple laptops. “Apple may have just gotten caught up in how cool the engineering is,” says Arment. “I know lots of people in the developer community who use these machines, and I have heard from zero people who are really taken with the Touch Bar.” It seems unlikely that the design team, composed mostly of veterans who have been together for many years, got “caught up” in “cool” engineering. But we expect Apple to make perfect choices, every time, and when it doesn’t we’re dismayed. “I have friends who are driven to absolute anger when Siri tries to be funny,” says Gruber, referring to Apple’s digital voice assistant, which is widely seen as inferior to Amazon’s Alexa or Google’s eponymous version. “If you tell Siri to cancel the timer you asked her to start so that you could cook something, instead of just saying, ‘I’ll cancel the timer,’ she usually says something like: ‘Okay, I’ve cancelled this, but don’t blame me if your egg overcooks!’ It drives people nuts. I think it’s the wrong way to go. They’re trying to humanize her, but it falls so flat. It just feels like they’re tone- deaf, especially when she does something like that and misinterprets your question.” Siri’s attempt at humor is as much a design decision as whether to include a Home button on the iPhone X. It’s an example of the complex new choices that designers at any company now face when developing a product with an Internet connection—toys, dishwashers, train engines, wine cellars, key chains, and more. So when Apple doesn’t get Siri right, it makes people worry about Apple’s future. The world of technology is growing increasingly complicated, and many people think that new product that most simplifies our life is the Amazon Echo. That can’t be a good sign, right??? For many Apple critics, the story ends right here. Siri’s not great, the Touch Bar’s kind of a mess, the operating systems are pretty but somewhat confusing, and the reassuring Home button has been killed … the list goes on. Apple’s far from perfect. Point made. But here’s the thing: Pick just about any time in Apple’s history, and you’ll find a similar set of worrying choices and seeming failures—even during those halcyon days of Steve Jobs’ triumphant second tenure at the company. 1998: that beautiful, bulbous, Bondi Blue iMac is actually an underpowered computer with an unreliable mouse and a CD slot that few consumers could use productively. 2000: The Power Mac G4 Cube, so gorgeous it becomes part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, doesn’t deliver the power and features heavy users demand. 2001: The first iPod is released, but it’s not really ready for primetime, since the scroll wheel is clunky and the device works only with Macs, which account for just 2.6% of worldwide PC sales. 2005: Apple’s in the phone business! With something called the Rokr, a kludgy music player/cell phone that the company developed with Motorola. 2007: The iPhone is introduced, with few applications and poor connectivity. 2011: The iPad is introduced, and, as my brother-in-law Mark told me at the time, “I can’t imagine anyone ever using this for anything interesting.” (He’s bought four since then.) In fact, Apple rarely gets it perfect at first. But over the years, the company has developed a long-term design process that regularly turns design “mistakes” into successes. The Apple Watch was introduced in 2015. Anticipation was high: Would this be Apple’s first Next Big Thing since the death of Jobs? “Apple introduced products like the iPod that were so great and worked so well that we started to question the design of other things in our life,” says Allan Chochinov, chair of the products of design program at New York City’s School of Visual Arts. “Why isn’t my thermostat like that?” Perhaps the time had come for a watch that was as great as an iPhone. As you may remember, the press was disappointed. To say the least. The user interface was a jumbled, layered, and unintuitive mess. The watch itself was attractive, but those who wore it to the gym found it clunky compared to established fitness trackers like Fitbit. Since it served up notifications only if your iPhone was nearby, and since it showed you the time only if you flicked up your wrist just so, I found it less useful than a Swatch—and about $300 more expensive. |

|

再看現(xiàn)在,新款手表已是3代,可以脫離iPhone單獨工作。新款手表內置移動通話功能,所以完全可以不帶iPhone,日常生活中所有數(shù)據(jù)和通訊功能都能完成同步。界面更簡化,使用智能手表真正擅長的功能,包括計時、健康追蹤、文本、電郵、日歷、音樂、蘋果支付、電子票券,甚至語音撥號都很方便。迅速回復簡單文字信息非常實用,雖然不太適合深入交流。蘋果手表里沒有塞入小鍵盤,而是準備好一些標準回復內容(“謝謝”,“一會回來”,“馬上到”,“在開會。一會打給你?”),可以輕點選擇,如果要回復別的內容也可以用手寫板。現(xiàn)在手表上的功能沒有讓人摸不清的了,設計上完全符合功能需求。 或許這正是近來手表銷量可觀的原因。調研公司Asymco創(chuàng)始人賀瑞斯·德第烏在最新發(fā)布的博文中估計,蘋果手表年銷量達1600萬塊。德第烏相信手表銷量還會繼續(xù)增長,超越巔峰時期的iPods,意味著手表可能變成蘋果歷史上第二受歡迎的產品。 為什么手表能如此迅速改進?第一代和第三代之間的兩年發(fā)生了什么?11月在華盛頓特區(qū)赫胥鴻博物館采訪伊夫時,我問到這個問題。“基本上我們所有精力都花在改進方面,”伊夫回答說。“有時我們知道有些技術還不成熟,也了解產品的發(fā)展趨勢。但有些事只有大規(guī)模做出產品,各種用戶使用之后才能發(fā)現(xiàn)。”在手表方面,蘋果用戶的激烈批評顯然影響了伊夫和團隊改善產品的走向。iPhone X則是設計團隊在非常成功產品的基礎上,結合新技術打造出的全新產品。 Touch Bar剛發(fā)布時的種種缺陷并不能代表蘋果設計水平。(MacBook Pro的買家可能并不同意,但這些一般是熱愛嘗鮮的用戶,所以都很清楚搶先體驗并不一定能用著舒服。)更重要的是接下來幾年蘋果如何改進技術。 創(chuàng)新過程向來是蘋果最高機密。基本目標是同步實現(xiàn)創(chuàng)新和改進,不僅要維持年年更新的頻率,也要經(jīng)常推出全新產品。但以蘋果龐大的體量,技術革新又如此迅速,沒有幾家公司有蘋果做得好。喬奇諾夫認為耐克和《紐約時報》算比較接近蘋果創(chuàng)新水平的兩家,但采訪中很多人表示找不到堪比蘋果的公司。“蘋果的設計水平超出別人很多,”埃蒙特表示。“蘋果有太多經(jīng)典產品,各種服務和軟件,大部分都很優(yōu)秀,至少可以說很不錯。之所以像我這樣的用戶喜歡挑三揀四,無非是被慣壞了。” 如果你也相信蘋果的設計在走下坡路,原因可能是喬布斯2011年去世后讓蘋果分心的事有點多。喬布斯去世六年里增長十分迅速,變化不斷發(fā)生。在首席執(zhí)行官蒂姆·庫克領導下,蘋果年銷售額翻了一倍多,亞洲銷量增至近三倍。除了開發(fā)出手表和藍牙耳機AirPods,蘋果還新開了160家門店(其中45家在中國),收購了幾十家公司(包括幾家做人工智能的,最近收購了一家做音樂識別軟件的Shazam),還成立了內容生產部門。 一些外部觀察家發(fā)覺,蘋果急速擴張似乎已對內部資源造成不小壓力。“看起來蘋果還沒完全適應龐大的規(guī)模,”特勞頓-史密斯表示,“而且蘋果缺乏足夠的工程設計力量支撐如此大的體量。”不過近幾年一直在改善,他表示。 伊夫個人方面也經(jīng)歷了重大轉變。喬布斯生命里的最后七年,庫克曾代理不少首席執(zhí)行官的職責,讓喬布斯專心與伊夫研發(fā)新產品。11月伊夫在赫胥鴻博物館告訴我,“你知道有時人與人之間心有靈犀的感覺么?(喬布斯和我)看待世界的方式都很怪,但出奇一致。如果你感覺奇怪,身邊有朋友同樣感覺奇怪,那就挺好的。”現(xiàn)在伊夫的故友已逝,肩上的重任卻比以往更重。伊夫一直是工業(yè)設計師,現(xiàn)在還要負責軟件設計。他就是蘋果產品設計的核心人物。 還有件事嚴重導致蘋果分心,也是喬布斯去世前不久開始的項目。打造新辦公室地點——蘋果公園過程中,伊夫一直承擔重要任務,要負責打磨所有細節(jié)。9月我參觀時,向導就努力介紹了很多點:跟蘋果筆記本上同樣鋁制的內凹型電梯按鈕,意大利石灰?guī)r樓梯欄桿上的圓形邊角,還有新咖啡廳里隔離食物的一次成型防護罩。 11月底,就在蘋果發(fā)布一系列操作系統(tǒng)更新修復漏洞后,《華盛頓郵報》一篇專欄文章里也提到修建蘋果公園可能是伊夫設計不力的原因。“蘋果應該有足夠資源同時建好新總部,也保證研發(fā)軟硬件不受影響,”該報前個人科技專欄作家表示,“但蘋果用戶感受到的情況并非如此。” 并沒有足夠證據(jù)表明蘋果公園建設牽扯了伊夫過多精力,影響正常的產品開發(fā)。但確實有些背景因素可以參考:伊夫2013年擔任首席設計官時,兩個負責工業(yè)設計和軟件設計的手下開始直接向庫克匯報。今年12月初,一向不愿討論公司內部變動的蘋果發(fā)布聲明,讓觀察者吃了一驚。蘋果稱,“隨著蘋果公園建設完工,設計團隊負責人和相關團隊將恢復直接向喬尼·伊夫匯報,伊夫仍將主管設計業(yè)務。” 這份聲明透露的意思很明確:即便之前有讓伊夫分心的事(蘋果肯定不會承認),現(xiàn)在都沒了。 史蒂夫·喬布斯去世后有一點從沒變過——科技行業(yè)的權力架構。Facebook、亞馬遜、谷歌(現(xiàn)在叫Alphabet)和蘋果2011年就掌控整個行業(yè),現(xiàn)在還是一樣。 當時根據(jù)傳統(tǒng)經(jīng)驗,人們預測四大巨頭之間會出現(xiàn)爭斗,每家都會攻擊對方實現(xiàn)自己增長。然而現(xiàn)在看來,各家巨頭只是各自發(fā)展,不斷鞏固最擅長的領域。谷歌仍然是在線搜索廣告巨頭。Facebook不懼任何社交媒體方面的挑戰(zhàn),移動領域廣告收入日漸超過PC。亞馬遜的商業(yè)模式是進攻各種新市場,效果非常明顯,現(xiàn)在所有可能受創(chuàng)的大公司都在努力制定發(fā)展戰(zhàn)略,避免某個意想不到的行業(yè)里冒出個競爭者來搶奪市場,也就是所謂的“亞馬遜化”。 以前人們都以為蘋果應該是四大巨頭里命運最不濟的,失去天才喬布斯后感覺要一蹶不振。但過去六年里,蒂姆·庫克成長為令人尊敬的首席執(zhí)行官,蘋果也變成全世界市值最高的公司,還發(fā)售了兩款極受歡迎的新品——AirPods和手表,這兩款產品可是喬布斯從未參與過的。 跟Alphabet、亞馬遜和Facebook類似,蘋果也日漸依賴自己的強項——設計。“可以說,蒂姆·庫克和手下團隊在設計方面下了雙倍工夫,”之前擔任分析師,如今專門撰寫蘋果相關博客的尼爾·賽巴特表示。“宣稱世界在變化所以人類已進入后設備時代的公司都沒意識到,設計是不可忽視的元素。科技行業(yè)從來不是只靠技術,不管是機器學習、人工智能還是語音助手——這些都是表面。關鍵在于人類如何去使用各種技術。而交互過程就是設計。硅谷的公司里,只有蘋果的公司文化是專注設計。” 要理解蘋果設計今后的競爭力,可以從思考未來的技術轉為思考未來的市場機會。醫(yī)療;無人汽車軟件和設計;可穿戴電腦;智能家居。每個市場都需要不同的技術。但每個市場都依賴設計。 蘋果會努力做好每個市場。具體過程當然需要多年研究。伊夫在赫胥鴻博物館向觀眾舉了個例子,就是計時器走向小型化的歷程,從大城市里的鐘樓到祖父的時鐘和懷表,再到如今手上小小的手表。從中也能體會到新想法和新技術如何被廣泛接受。那次采訪中,伊夫介紹了新總部里的設計室。設計空間會非常大,第一次所有與產品設計相關的人可以聚在一處。用戶體驗專家可能跟工業(yè)設計師坐一起,可能觸覺專家旁邊就是美術設計師。可以肯定,蘋果的未來,當然也包括現(xiàn)在不會僅靠工業(yè)設計,不會再是銀匠兒子伊夫成長過程中學習的工業(yè)設計。伊夫相信,新辦公空間將拓展激發(fā)蘋果內部設計部門相互交流,再次設計出超出想象的新產品。 他在赫胥鴻博物館告訴觀眾,對蘋果未來的設想讓他“忍不住灰常激動”。就是這么古怪奇特,但又充滿希望。(財富中文網(wǎng)) 本文另一版本將發(fā)表于2018年1月1日出版的《財富》雜志,為《設計的世界》組文其中一篇。 譯者:Min |

Cut to present-day. The new Watch, called Series 3, works independently from the iPhone. With cellular capability built in, I can now leave my iPhone behind and keep up to date with all the data and communications we’ve absorbed into our daily routines. The interface is simpler, and Apple has made it easier for me to access the things that a smartwatch is really good for, including timer, fitness tracker, texts, email, calendar, music, Apple Pay, mobile tickets, and even voice calling. It’s great for responding quickly and simply to texts, even if it’s not for deeply felt communication. Instead of trying to cram some sort of keyboard replacement into the watch, Apple has provided a set of canned responses (“Thanks,” “BRB,” “On my way,” “In a meeting. Call you later?”) that I can quickly tap, along with a scribble pad if I want to get more specific. Nothing about the Watch is confusing any more—its design perfectly suits its purpose. That’s probably why it’s selling so briskly now. In a recent blog post, Asymco’s Horace Dediu estimated that Apple is now selling 16 million a year. Dediu believes Watch sales will eventually grow bigger than sales of iPods at their peak, which would make the Watch Apple’s second most popular product ever. How did the Watch get so much better so quickly? What happened in the two years between the first and third editions of the Watch? I asked Ive this question during a November interview at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. “Mostly, we spend all our time looking at what we can do better,” Ive responded. “Sometimes we are very aware that there are technologies that aren’t ready. We’re very aware of where the product is going. Then there are things that you don’t truly know until you’ve made them in large volumes, and a really diverse group of people use them.” In the case of the Watch, the loud and ample criticism from Apple customers clearly shaped the way Ive and his team improved the product. The iPhone X, on the other hand, seems more the creative brainchild of a team integrating new technologies to build something new on the foundation of an already successful product. The flaws in the first iteration of the Touch Bar don’t tell us anything about the state of Apple design. (MacBook Pro buyers may disagree—but they tend to be early adopters, who know that the cutting edge isn’t always pretty.) What’s more important is how Apple develops the technology in the years ahead. This creative process is Apple’s secret sauce. Its goal—innovating and improving simultaneously, delivering both annual updates and the occasional brand-new product—is commonplace. But few companies have done it as well as Apple, at mass scale over a long period of dramatic technological change. Chochinov cites Nike and the New York Times as two that have, but many of the sources I interviewed for this story couldn’t think of any comparable peers. “Apple design is so far ahead of everyone else,” says Arment. “Apple has so many products and so many services and so much software out there, and most of it is great—or at least fine. The reason people like me can nitpick is that we have been spoiled.” If you are one of those people who believes there’s been a slump in Apple design, you might attribute some of that to the many distractions Apple has faced since the death of Steve Jobs in 2011. The six years since Jobs’ death have been marked by outrageous growth and continual change. Under CEO Tim Cook, annual sales have more than doubled, and almost tripled in Asia. Besides introducing new products like the Watch and AirPods, Apple has opened 160 new stores (including 45 in China), acquired companies (including several focused on artificial intelligence and, most recently, the music recognition app, Shazam), and launched its own content creation arm. Some outside observers sensed that the explosive expansion appeared to put a strain on resources for a while. “Apple seemed to struggle with its newfound scale,” says Troughton-Smith,” and appeared to not have the engineering practices in place to support the new status quo.” That’s improved in the past couple of years, he says. It has been a period of big transitions for Ive personally too. During the last seven years of Jobs’ life, Cook had performed many of the duties of a standard CEO, leaving Jobs free to develop products with Ive. As Ive told me at the Hirshhorn in November, “You know how sometimes something just clicks with someone? [Steve and I] had a bizarre way of looking at the world, but it was the same. When you feel odd and bizarre, it’s nice to feel odd and bizarre with a friend.” Now Ive is without his old friend and yet charged with greater responsibility than ever. An industrial designer all his life, Ive now oversees software design as well. He is Apple’s product guy. There’s been one other serious distraction, something Jobs set in motion shortly before his death. Ive has been a central player in the creation of Apple Park, the company’s new campus, fretting every detail. When I took a tour of the place in September, my guide took pains to point out many of them: the concave elevator buttons in the same brushed aluminum used on Apple laptops, the rounded edges of the rail on an Italian limestone staircase, the single-piece sneeze guard that will protect the food in the new café. The idea that the project may have caused Ive to drop the ball on product quality was alluded to in a Washington Post column in late November, shortly after Apple had to issue a series of operating system updates to repair a security flaw. “While the company should have sufficient resources to obsess over both its headquarters and its software and hardware,” wrote the paper’s former personal-tech columnist, “the reality seen by Apple customers suggests otherwise.” There’s simply not enough evidence to prove that Ive’s focus on Apple Park distracted him from regular product development. However, there is this bit of context: When Ive was given the title of chief design officer in 2013, his two lieutenants overseeing industrial design and software design started reporting directly to Cook. Then in early December, Apple, which is usually very reluctant to discuss internal corporate machinations, surprised observers by issuing the following statement: “With the completion of Apple Park, Apple’s design leaders and teams are again reporting directly to Jony Ive, who remains focused purely on design.” The message seemed clear: If there had been any distractions for Ive (something Apple would never admit), there won’t be any going forward.?? One thing hasn’t changed since Steve Jobs died—the power structure of the technology industry. Facebook, Amazon, Google (now Alphabet), and Apple dominated tech in 2011, and they dominate it today. Back then, conventional wisdom forecast a battle royale between the four, with each trying to grow by attacking the others’ strongholds. Instead, each has grown outlandishly by becoming even more entrenched in the field it dominates. Google is still the behemoth in online search advertising. Facebook has dismissed all challengers in social media and become an even more-powerful revenue generator on mobile than it was on the desktop. Amazon’s business model for efficiently attacking new business sectors is so potent that every large company worth its salt now strategizes about how to avoid getting “Amazoned” by an unimaginable competitor from some unlikely industry. Apple was supposedly the most vulnerable of the four, doomed without the unique genius of Jobs. But over the past six years, Tim Cook has grown into a widely respected CEO, while Apple has become the world’s most valuable company, and has introduced two hit products—AirPods and the Watch—that don’t have even a wisp of a Steve Jobs fingerprint on them. Like Alphabet, Amazon, and Facebook, Apple continues to rely on its unique strength—design. “If anything, Tim Cook and his team have doubled down on design,” says Neil Cybart, a former research analyst who now pens his own astute Apple blog. “The companies that are saying that the world is changing and we’re moving into a post-device era are the companies who haven’t figured out that design is the missing ingredient. It’s never just about the technologies, like machine learning, A.I., voice assistants—it’s never just about those things. It’s about how should we use those things. That’s design. And no other company in Silicon Valley has a design focus and culture like Apple.” One way to understand the competitive power of Apple’s design is to shift from thinking of the technologies of the future to the market opportunities of the future. Health care; the software and design of autonomous vehicles; wearable computers; the connected products in our homes. Each market will need different technologies. But every market will depend on design. Apple will explore how it can make its mark on each of these markets. That process entails years of research—at the Hirshhorn, for example, Ive regaled the audience with a distilled history of the miniaturization of timepieces, from the single clock in big cities to grandfather clocks, pocket watches, and the tiny thing on your wrist. And it entails a catholic receptivity to new ideas and technologies. During the same interview, Ive described the design studio at the new campus. The new space is so large that, for the first time, everyone involved in product design will be gathered in one space. The user experience experts will be mixed in with the industrial designers, and the haptics specialists might find themselves sitting next to a graphic designer. It’s a conscious, visible acknowledgement that Apple’s future—its present, too—depends on so much more than just the industrial design that Ive, whose father was a silversmith, was raised on. Ive believes that the new space will expand and spark Apple’s internal design conversation, leading the company once again to products we can’t quite imagine now. The prospect, he told the audience at the Hirshhorn, gets him “uppity uppity jumpy.” How odd and bizarre. How promising. A version of this article appears as part of our “Business by Design” package in the Jan. 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |