2019年4月,美國(guó)七大銀行的首席執(zhí)行官出席了眾議院金融服務(wù)委員會(huì)的會(huì)議。在委員會(huì)成員宣誓時(shí),在場(chǎng)的清一色全是白人男性,當(dāng)他們被問到他們的繼任者是否可能是女性或有色人種時(shí),沒有人舉手。

這片沉默凸顯了一個(gè)鐵一般的事實(shí):華爾街從來沒有女首席執(zhí)行官,而且不久的將來也不會(huì)有。

然而,這一事實(shí)與當(dāng)時(shí)美國(guó)企業(yè)界的變革情緒背道而馳。

#MeToo運(yùn)動(dòng)推動(dòng)人們重新審視辦公室文化。機(jī)構(gòu)投資者開始要求董事會(huì)增加女性,包括銀行在內(nèi)的各種公司都在宣揚(yáng)多元化。

然而開頭的那一幕實(shí)在令人失望。

后來,《財(cái)富》雜志在2019年《全球最具影響力的商界女性》專刊中特地留出數(shù)頁(yè),提出了三個(gè)緊迫的問題:為什么銀行首席執(zhí)行官這一職位對(duì)女性來說仍然如此難以觸及?誰可能成為第一個(gè)突破者?而這一突破何時(shí)才會(huì)來臨?

對(duì)于后面兩個(gè)問題,現(xiàn)在有了明確的答案:今年9月中旬花旗集團(tuán)宣布,簡(jiǎn)·弗雷澤(Jane Fraser)將于明年2月接替高沛德(Michael Corbat)出任首席執(zhí)行官。

除非出現(xiàn)不可預(yù)知的變故,長(zhǎng)期以來華爾街銀行的隱形天花板已經(jīng)成為歷史。

但弗雷澤的任命并未徹底消除多年來女性無緣出任高層領(lǐng)導(dǎo)的文化。

這又引發(fā)了一系列新問題:首位出任華爾街大型銀行首席執(zhí)行官的女性是誰?她如何實(shí)現(xiàn)這一看起來似乎無法實(shí)現(xiàn)的目標(biāo)的?

一方面,弗雷澤職業(yè)生涯的最新一步非常符合簡(jiǎn)·史蒂芬森所說的“成功路線圖”,史蒂芬森是高管獵頭公司光輝國(guó)際里首席執(zhí)行官接任部門的負(fù)責(zé)人。

具體來說,她在花旗各個(gè)關(guān)鍵業(yè)務(wù)部門都工作過,每次離任時(shí)的業(yè)務(wù)狀況都比她剛接手時(shí)好。而與此同時(shí),她拒絕為了追求事業(yè)犧牲個(gè)人生活,違反了以往很多成功登頂?shù)呐f“規(guī)則”。

這種如同在古老迷宮中闖新路一般的尋找折中之道的能力,可能正是她格外適合這份工作的關(guān)鍵。

也正因如此,她愿意坦率談?wù)撨@份闖出迷宮的經(jīng)驗(yàn)。

弗雷澤現(xiàn)年53歲,出生于蘇格蘭圣安德魯斯,熱愛打高爾夫球。

她高中搬到了澳大利亞,最初渴望成為一名醫(yī)生。但她很快發(fā)現(xiàn)自己學(xué)不好生物,卻格外擅長(zhǎng)數(shù)學(xué)和經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué),于是自然而然向銀行業(yè)發(fā)展。

弗雷澤畢業(yè)于劍橋大學(xué),20歲就在倫敦的高盛公司工作。多年后,她感嘆自己是辦公室里“無聊的英國(guó)女孩”。

“其他人來自歐洲各地,更具異國(guó)情調(diào)。他們年紀(jì)稍長(zhǎng),會(huì)說多種語言,我覺得他們比我有趣得多。”2016年,她在智庫(kù)美洲理事會(huì)和美洲協(xié)會(huì)的一次演講中說道。

這種感覺促使她離開了倫敦,前往馬德里,在咨詢公司Asesores Bursátiles擔(dān)任了兩年分析師,期間提升了西班牙語能力。多年后這項(xiàng)技能發(fā)揮了巨大作用。

上世紀(jì)90年代初,她從哈佛商學(xué)院畢業(yè)后,職業(yè)生涯進(jìn)一步偏離了典型的銀行業(yè)成長(zhǎng)軌跡。

她加入了麥肯錫,同時(shí)直言不諱地表達(dá)了做出這一選擇的原因是,她認(rèn)為銀行業(yè)的女性讓人“望而生畏”,她在2016年的演講中表示。

那是一個(gè)流行女性戴大墊肩,穿男性化西裝的年代。浸泡在銀行業(yè)的女性和很多男性似乎沒有“那么幸福,”她回憶說,“他們確實(shí)非常成功,也很聰明。但很艱苦。”

簡(jiǎn)而言之:她想要正常的生活。

在麥肯錫工作的強(qiáng)度也很大,但同樣有催人奮進(jìn)的動(dòng)力:成為值得信賴的顧問,盡可能準(zhǔn)確地幫客戶進(jìn)行預(yù)測(cè)。

兩年之后,她結(jié)婚了,并于有望升級(jí)為合伙人的那年懷孕。

“很多人建議我,‘要升合伙人的時(shí)候別懷孕。’但我覺得這簡(jiǎn)直就是胡說八道。”在今年10月《財(cái)富》最具影響力的商界女性峰會(huì)上,她對(duì)我說道。

她生孩子兩周后,公司通知她成為了合伙人。

在此之后,她確實(shí)聽取了另一條建議:“我記得一位導(dǎo)師曾經(jīng)對(duì)我說:‘你一生中會(huì)有好幾份職業(yè),要從幾十年的視角進(jìn)行衡量。為什么要著急,恨不得一步登天呢?’”

這番話刺激她做出了一個(gè)至關(guān)重要的決定,在麥肯錫當(dāng)合伙人的五年全是兼職,并于2004年離開麥肯錫,去了花旗工作。

“做這個(gè)決定并不容易,我感到自尊受挫——因?yàn)槟軌蚩吹侥切]有自己資深的人職業(yè)發(fā)展更快。”她說,“但我真正感受到快樂,實(shí)現(xiàn)了工作和個(gè)人生活的平衡。”

那段經(jīng)歷改變了她職業(yè)觀,也改變了她在辦公室工作的方式。

弗雷澤說:“當(dāng)我回到工作崗位全職工作時(shí),客戶經(jīng)常告訴我:‘現(xiàn)在的你更有同理心,以前的你只是臺(tái)機(jī)器。’”

2004年,弗雷澤加入花旗,擔(dān)任倫敦投資和企業(yè)銀行業(yè)務(wù)部客戶戰(zhàn)略主管。此時(shí)的她又演回了銀行業(yè)的劇本,卻開始再次不走尋常路。

在接下來16年里,她在花旗擔(dān)任了一系列的工作,從中學(xué)習(xí)了不同部門的業(yè)務(wù),積攢了領(lǐng)導(dǎo)獨(dú)立核算部門的經(jīng)驗(yàn),也獲得了在公司內(nèi)部建立聯(lián)系和打造名聲的機(jī)會(huì)。

“看她的背景就知道。”史蒂文森說。弗雷澤的輪崗“是持續(xù)積累的10年,這是一個(gè)巧妙的過程。”她說。董事會(huì)考慮接班人時(shí),“這種工作經(jīng)歷會(huì)提升可信度”。

當(dāng)然,如果其中一些崗位需要做出艱難決策,或需要處理陷入困境的業(yè)務(wù),這種經(jīng)歷確實(shí)會(huì)有所幫助,但前提是要證明自己有能力應(yīng)對(duì)得當(dāng)。

2007年9月,隨著金融危機(jī)加劇,時(shí)任首席財(cái)務(wù)官的加里·克里滕登讓弗雷澤擔(dān)任全球戰(zhàn)略與并購(gòu)主管。她在接受這份工作后搬到紐約,協(xié)助時(shí)任首席執(zhí)行官的潘偉迪(Vikram Pandit)判斷如何收縮銀行規(guī)模。

她策劃了將花旗日本證券業(yè)務(wù)出售給三井住友金融集團(tuán)的交易,作價(jià)80億美元。這幫助2009年的花旗獲得了亟需的資本金。除此之外,她還為花旗將美邦經(jīng)紀(jì)業(yè)務(wù)出售給摩根士丹利打好了基礎(chǔ)。

任職期間,她在18個(gè)月內(nèi)完成了超過25筆交易。在這一過程中花旗出售了價(jià)值近萬億美元的資產(chǎn),裁員10萬人。

弗雷澤回憶稱,那段工作是她作為領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者的重要經(jīng)歷之一。

“當(dāng)你真正能身處其位時(shí),才能切實(shí)了解情況,不會(huì)流于空泛。”10月她告訴我。

“究竟要怎么做,才可以避免讓客戶驅(qū)動(dòng)只是停留在墻上的口號(hào)?你做了哪些戰(zhàn)略決策?及早著手,認(rèn)真應(yīng)對(duì),然后逐漸累積優(yōu)勢(shì)爭(zhēng)取勝利……危機(jī)當(dāng)中的學(xué)習(xí)曲線最陡峭。”

盡管并購(gòu)業(yè)務(wù)的經(jīng)歷很有價(jià)值,弗雷澤還是想實(shí)際經(jīng)營(yíng)企業(yè)。

2009年,潘偉迪給了她機(jī)會(huì),讓她回倫敦工作四年,擔(dān)任花旗私人銀行負(fù)責(zé)人,為花旗最富裕的客戶提供服務(wù)。這份工作相當(dāng)吸引人,尤其是與接下來在圣路易斯擔(dān)任花旗抵押貸款公司的首席執(zhí)行官相比。

2013年她接手該工作,而這段經(jīng)歷正如她在2016年演講中所承認(rèn)的,當(dāng)時(shí)的抵押貸款業(yè)務(wù)如同次貸危機(jī)后的“地球劫難”。在她執(zhí)掌下,花旗經(jīng)歷了緩慢而痛苦的恢復(fù)過程,主要因?yàn)槎嗄昵盎ㄆ煸?jīng)向房利美和房地美出售不良抵押貸款,并為處理索賠支付了數(shù)億美元。

2015年,高沛德任命弗雷澤為花旗拉丁美洲業(yè)務(wù)首席執(zhí)行官,她再次獲得機(jī)會(huì)力挽狂瀾。

按凈收入計(jì)算,拉丁美洲在花旗地區(qū)分部中規(guī)模最小但利潤(rùn)率最高,如同皇冠上的寶石。

花旗在墨西哥的零售部門,當(dāng)時(shí)被稱為墨西哥國(guó)家銀行或Banamex,是墨西哥最大的銀行之一,分行達(dá)1400家,占花旗全球?qū)嶓w分支機(jī)構(gòu)一半以上。

在弗雷澤接手時(shí),該業(yè)務(wù)深陷泥潭。

2014年2月,花旗披露稱石油服務(wù)公司Oceanografía涉嫌從Banamex騙取了4億美元。幾個(gè)月后,Banamex發(fā)現(xiàn)某個(gè)為高管提供安全保障的部門員工向外部提供未經(jīng)授權(quán)的服務(wù),且從事非法活動(dòng),因此隨后解散了該部門。

2017年,在接受《美國(guó)銀行家》雜志采訪時(shí),弗雷澤談到要改變花旗在拉丁美洲的文化,不能再讓員工“對(duì)問題惡化視若不見,而是要主動(dòng)提出,‘我對(duì)老板的做法感到不安。’”

這項(xiàng)工作很重要一步就是讓員工相信,舉報(bào)不當(dāng)行為之后,銀行確實(shí)會(huì)采取對(duì)應(yīng)行動(dòng)。

“這很大程度上取決于信任。”她說。人們必須相信“他們提出問題不會(huì)惹禍上身,且公司會(huì)采取措施處理。”

弗雷澤出任拉美業(yè)務(wù)首席執(zhí)行官后,拉美分部還出售了巴西、阿根廷和哥倫比亞等國(guó)的消費(fèi)銀行和信用卡業(yè)務(wù),更專注于當(dāng)?shù)貦C(jī)構(gòu)業(yè)務(wù)。

與此同時(shí),花旗向墨西哥注入了10億美元,墨西哥是拉美國(guó)家當(dāng)中唯一仍然有零售業(yè)務(wù)的國(guó)家。

2016年,花旗宣布了為期四年的投資,主要通過升級(jí)自動(dòng)柜員機(jī)、提供新型數(shù)字工具和分行改造來提升客戶體驗(yàn)。

弗雷澤任職期間,拉丁美洲分部的凈收入和凈利潤(rùn)分別增長(zhǎng)了8%和38%。

弗雷澤在這之后一次升職是在2019年10月,出任全球消費(fèi)者銀行總裁兼首席執(zhí)行官。這也表明她在拉美分公司的工作受到首肯,從而邁上新臺(tái)階。

從同事們口中透露出的跡象也可證實(shí),弗雷澤是高沛德的繼承人。

“消費(fèi)業(yè)務(wù)占收入一半,也是直線經(jīng)營(yíng)業(yè)務(wù),現(xiàn)在都交給了她,還讓她當(dāng)這塊業(yè)務(wù)的總裁,這就是準(zhǔn)備讓她當(dāng)首席執(zhí)行官。”花旗集團(tuán)主席約翰·杜根說。

不過花旗正式任命弗雷澤為首席執(zhí)行官的時(shí)間比預(yù)期的要快。

弗雷澤被任命為總裁時(shí),高沛德曾經(jīng)表示他還要在花旗工作“幾年”,然而11個(gè)月后,公司便宣布二號(hào)人物上位。

在領(lǐng)英的一篇帖子中,高沛德自稱“堅(jiān)決支持任期限制”。

杜根說,高沛德一直計(jì)劃2021年離任,但如今決定將時(shí)間提前,以便弗雷澤能夠“實(shí)際掌控”花旗改善控制和風(fēng)險(xiǎn)流程的進(jìn)度。

時(shí)間表的提前也給了花旗董事會(huì)領(lǐng)先優(yōu)勢(shì),使其成為了華爾街首家提名女性首席執(zhí)行官的大銀行。

“我們很高興能夠率先實(shí)現(xiàn)突破,也很高興公司里有極為適合這份工作的候選人。”杜根說。

從很多方面看,弗雷澤強(qiáng)悍的簡(jiǎn)歷與以前大型銀行的首席執(zhí)行官有相似之處,但她對(duì)工作的態(tài)度卻并不一定符合過往領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者的模式。

很多首席執(zhí)行官都不愿承認(rèn)自我懷疑的存在,她似乎不怕談起。

她說,獲得擔(dān)任全球戰(zhàn)略與并購(gòu)主管的第一反應(yīng)是,憑自己的能力難以勝任。

后來還是一位朋友說服了她:“你為什么擔(dān)心失敗?盡力試試。就算失敗又有什么關(guān)系?”

弗雷澤愿意談?wù)摴ぷ髦腥诵曰囊幻妫瑹o論是缺乏自信、為人父母的壓力,亦或是銀行文化過往的失敗。她不僅在華爾街同輩中鶴立雞群,就算與其他在各自行業(yè)中“登頂”的女性相比也毫不遜色。

有些女性會(huì)擔(dān)心,如果公開這類想法,會(huì)容易被貼上女首席執(zhí)行官的標(biāo)簽。而弗雷澤則認(rèn)為這種坦誠(chéng)是優(yōu)勢(shì):“在某些方面,我可能更容易受到傷害,我的一些男性同事不太愿意談?wù)撨@一問題的人性層面。”5月她告訴我,“這不代表軟弱或無力,我認(rèn)為這會(huì)使我更強(qiáng)大。”

在被派往拉丁美洲之前,弗雷澤曾接替現(xiàn)已退休的塞西莉亞·斯圖爾特?fù)?dān)任花旗美國(guó)消費(fèi)者和商業(yè)銀行首席執(zhí)行官。領(lǐng)導(dǎo)層交接期間,兩人會(huì)見了全國(guó)各地的銀行家。

斯圖爾特回憶說,弗雷澤可以“很自然地坐下來和別人交談,而且不論工作上還是生活上都可以迅速建立聯(lián)系。”

“不管是男性還是女性,擁有飽含如此同理心的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)風(fēng)格,能夠坦誠(chéng)地討論各種情況非常重要。”斯圖爾特說。

這種領(lǐng)導(dǎo)風(fēng)格尤其適合應(yīng)對(duì)疫情。“對(duì)美國(guó)企業(yè)界來說,2021年和2022年可能截然不同。”斯圖爾特表示,“因此,花旗能有這樣一位靈活,并愿意以開放心態(tài)領(lǐng)導(dǎo)公司經(jīng)歷變革的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)人,無論結(jié)果怎樣,都是好事。”

當(dāng)然,打破這層隱形天花板只是開始。這位大型銀行圈子里的首位女首席執(zhí)行官所接手的并非是一臺(tái)運(yùn)轉(zhuǎn)良好的機(jī)器。

花旗任命弗雷澤為首席執(zhí)行官后不到一個(gè)月,美聯(lián)儲(chǔ)和美國(guó)貨幣監(jiān)理署均指責(zé)該行風(fēng)險(xiǎn)控制長(zhǎng)期存在缺陷,為此花旗同意支付4億美元。

而在此前的8月,花旗集團(tuán)曾經(jīng)向Revlon lenders誤匯了9億美元,約為正確金額的100倍。

根據(jù)貨幣監(jiān)理署的指令,監(jiān)管方面有權(quán)否決花旗的重大收購(gòu),必要時(shí)還可以強(qiáng)制要求花旗高管團(tuán)隊(duì)或董事會(huì)變更。

監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)“一般不會(huì)如此嚴(yán)厲,除非真被惹怒,”喬治·華盛頓大學(xué)的法學(xué)教授,曾經(jīng)研究銀行監(jiān)管的亞瑟·威爾馬思表示。

花旗在一份聲明中表示,對(duì)于未能達(dá)到監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)的預(yù)期深表失望,“正實(shí)施深層整改”。

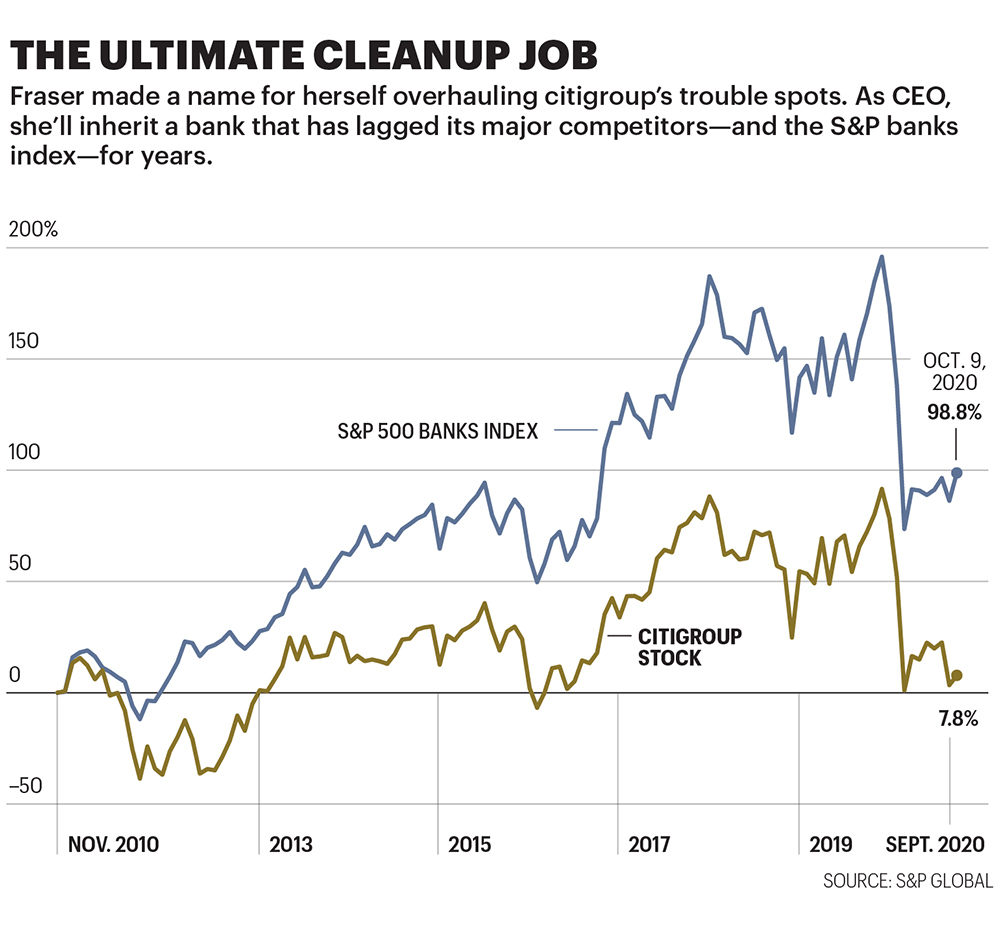

投資者也渴望弗雷澤能夠解決花旗的盈利能力問題。因?yàn)殚L(zhǎng)期以來,花旗一直落后于華爾街的其他競(jìng)爭(zhēng)對(duì)手。

此外,另一大挑戰(zhàn)是對(duì)花旗的控制。

“當(dāng)前正面臨疫情和經(jīng)濟(jì)衰退夾擊。貸款損失將上升,利率也處于歷史低位。”巴克萊銀行的分析師杰森·戈德伯格表示。可以說,現(xiàn)在對(duì)銀行家來說,是非常艱難的時(shí)期。

監(jiān)管舉措對(duì)花旗來說是一記重拳,但威爾馬思認(rèn)為,從某種程度上說,這其實(shí)鞏固了弗雷澤的地位。這種情況下,“如果沒有監(jiān)管者默許,我懷疑她很難順利晉升。”威爾馬思說。(花旗對(duì)此拒絕置評(píng)。)

戈德伯格說,從弗雷澤的過往經(jīng)歷來看,她確實(shí)適合此時(shí)上任。花旗“需要一些調(diào)整,”他指出,“她在清理業(yè)務(wù)和扭轉(zhuǎn)局面方面經(jīng)驗(yàn)豐富。”

弗雷澤在10月的談話中也對(duì)此表示了認(rèn)同。

面對(duì)任何危機(jī),“都要回過頭來說:‘出現(xiàn)問題的根本原因是什么,如何將危局變成機(jī)會(huì),真正實(shí)現(xiàn)跨越式發(fā)展,推動(dòng)銀行邁上新臺(tái)階?’”弗雷澤說。“如何激勵(lì)公司朝著正確的方向努力?我在私人銀行成功過,在抵押貸款部門成功過,在墨西哥也成功過。現(xiàn)在有機(jī)會(huì)能帶領(lǐng)花旗,我對(duì)此感到很興奮。”

今年9月,弗雷澤成了第一位獲得華爾街首席執(zhí)行官職位的女性。到了明年2月,她將正式成為花旗掌門人。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

本文另一版本登載于《財(cái)富》雜志2020年11月刊,標(biāo)題為《華爾街第一女性》。

譯者:夏林

編輯:徐曉彤

2019年4月,美國(guó)七大銀行的首席執(zhí)行官出席了眾議院金融服務(wù)委員會(huì)的會(huì)議。在委員會(huì)成員宣誓時(shí),在場(chǎng)的清一色全是白人男性,當(dāng)他們被問到他們的繼任者是否可能是女性或有色人種時(shí),沒有人舉手。

這片沉默凸顯了一個(gè)鐵一般的事實(shí):華爾街從來沒有女首席執(zhí)行官,而且不久的將來也不會(huì)有。

然而,這一事實(shí)與當(dāng)時(shí)美國(guó)企業(yè)界的變革情緒背道而馳。

#MeToo運(yùn)動(dòng)推動(dòng)人們重新審視辦公室文化。機(jī)構(gòu)投資者開始要求董事會(huì)增加女性,包括銀行在內(nèi)的各種公司都在宣揚(yáng)多元化。

然而開頭的那一幕實(shí)在令人失望。

后來,《財(cái)富》雜志在2019年《全球最具影響力的商界女性》專刊中特地留出數(shù)頁(yè),提出了三個(gè)緊迫的問題:為什么銀行首席執(zhí)行官這一職位對(duì)女性來說仍然如此難以觸及?誰可能成為第一個(gè)突破者?而這一突破何時(shí)才會(huì)來臨?

對(duì)于后面兩個(gè)問題,現(xiàn)在有了明確的答案:今年9月中旬花旗集團(tuán)宣布,簡(jiǎn)·弗雷澤(Jane Fraser)將于明年2月接替高沛德(Michael Corbat)出任首席執(zhí)行官。

除非出現(xiàn)不可預(yù)知的變故,長(zhǎng)期以來華爾街銀行的隱形天花板已經(jīng)成為歷史。

但弗雷澤的任命并未徹底消除多年來女性無緣出任高層領(lǐng)導(dǎo)的文化。

這又引發(fā)了一系列新問題:首位出任華爾街大型銀行首席執(zhí)行官的女性是誰?她如何實(shí)現(xiàn)這一看起來似乎無法實(shí)現(xiàn)的目標(biāo)的?

一方面,弗雷澤職業(yè)生涯的最新一步非常符合簡(jiǎn)·史蒂芬森所說的“成功路線圖”,史蒂芬森是高管獵頭公司光輝國(guó)際里首席執(zhí)行官接任部門的負(fù)責(zé)人。

具體來說,她在花旗各個(gè)關(guān)鍵業(yè)務(wù)部門都工作過,每次離任時(shí)的業(yè)務(wù)狀況都比她剛接手時(shí)好。而與此同時(shí),她拒絕為了追求事業(yè)犧牲個(gè)人生活,違反了以往很多成功登頂?shù)呐f“規(guī)則”。

這種如同在古老迷宮中闖新路一般的尋找折中之道的能力,可能正是她格外適合這份工作的關(guān)鍵。

也正因如此,她愿意坦率談?wù)撨@份闖出迷宮的經(jīng)驗(yàn)。

弗雷澤現(xiàn)年53歲,出生于蘇格蘭圣安德魯斯,熱愛打高爾夫球。

她高中搬到了澳大利亞,最初渴望成為一名醫(yī)生。但她很快發(fā)現(xiàn)自己學(xué)不好生物,卻格外擅長(zhǎng)數(shù)學(xué)和經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué),于是自然而然向銀行業(yè)發(fā)展。

弗雷澤畢業(yè)于劍橋大學(xué),20歲就在倫敦的高盛公司工作。多年后,她感嘆自己是辦公室里“無聊的英國(guó)女孩”。

“其他人來自歐洲各地,更具異國(guó)情調(diào)。他們年紀(jì)稍長(zhǎng),會(huì)說多種語言,我覺得他們比我有趣得多。”2016年,她在智庫(kù)美洲理事會(huì)和美洲協(xié)會(huì)的一次演講中說道。

這種感覺促使她離開了倫敦,前往馬德里,在咨詢公司Asesores Bursátiles擔(dān)任了兩年分析師,期間提升了西班牙語能力。多年后這項(xiàng)技能發(fā)揮了巨大作用。

上世紀(jì)90年代初,她從哈佛商學(xué)院畢業(yè)后,職業(yè)生涯進(jìn)一步偏離了典型的銀行業(yè)成長(zhǎng)軌跡。

她加入了麥肯錫,同時(shí)直言不諱地表達(dá)了做出這一選擇的原因是,她認(rèn)為銀行業(yè)的女性讓人“望而生畏”,她在2016年的演講中表示。

那是一個(gè)流行女性戴大墊肩,穿男性化西裝的年代。浸泡在銀行業(yè)的女性和很多男性似乎沒有“那么幸福,”她回憶說,“他們確實(shí)非常成功,也很聰明。但很艱苦。”

簡(jiǎn)而言之:她想要正常的生活。

在麥肯錫工作的強(qiáng)度也很大,但同樣有催人奮進(jìn)的動(dòng)力:成為值得信賴的顧問,盡可能準(zhǔn)確地幫客戶進(jìn)行預(yù)測(cè)。

兩年之后,她結(jié)婚了,并于有望升級(jí)為合伙人的那年懷孕。

“很多人建議我,‘要升合伙人的時(shí)候別懷孕。’但我覺得這簡(jiǎn)直就是胡說八道。”在今年10月《財(cái)富》最具影響力的商界女性峰會(huì)上,她對(duì)我說道。

她生孩子兩周后,公司通知她成為了合伙人。

在此之后,她確實(shí)聽取了另一條建議:“我記得一位導(dǎo)師曾經(jīng)對(duì)我說:‘你一生中會(huì)有好幾份職業(yè),要從幾十年的視角進(jìn)行衡量。為什么要著急,恨不得一步登天呢?’”

這番話刺激她做出了一個(gè)至關(guān)重要的決定,在麥肯錫當(dāng)合伙人的五年全是兼職,并于2004年離開麥肯錫,去了花旗工作。

“做這個(gè)決定并不容易,我感到自尊受挫——因?yàn)槟軌蚩吹侥切]有自己資深的人職業(yè)發(fā)展更快。”她說,“但我真正感受到快樂,實(shí)現(xiàn)了工作和個(gè)人生活的平衡。”

那段經(jīng)歷改變了她職業(yè)觀,也改變了她在辦公室工作的方式。

弗雷澤說:“當(dāng)我回到工作崗位全職工作時(shí),客戶經(jīng)常告訴我:‘現(xiàn)在的你更有同理心,以前的你只是臺(tái)機(jī)器。’”

2004年,弗雷澤加入花旗,擔(dān)任倫敦投資和企業(yè)銀行業(yè)務(wù)部客戶戰(zhàn)略主管。此時(shí)的她又演回了銀行業(yè)的劇本,卻開始再次不走尋常路。

在接下來16年里,她在花旗擔(dān)任了一系列的工作,從中學(xué)習(xí)了不同部門的業(yè)務(wù),積攢了領(lǐng)導(dǎo)獨(dú)立核算部門的經(jīng)驗(yàn),也獲得了在公司內(nèi)部建立聯(lián)系和打造名聲的機(jī)會(huì)。

“看她的背景就知道。”史蒂文森說。弗雷澤的輪崗“是持續(xù)積累的10年,這是一個(gè)巧妙的過程。”她說。董事會(huì)考慮接班人時(shí),“這種工作經(jīng)歷會(huì)提升可信度”。

當(dāng)然,如果其中一些崗位需要做出艱難決策,或需要處理陷入困境的業(yè)務(wù),這種經(jīng)歷確實(shí)會(huì)有所幫助,但前提是要證明自己有能力應(yīng)對(duì)得當(dāng)。

2007年9月,隨著金融危機(jī)加劇,時(shí)任首席財(cái)務(wù)官的加里·克里滕登讓弗雷澤擔(dān)任全球戰(zhàn)略與并購(gòu)主管。她在接受這份工作后搬到紐約,協(xié)助時(shí)任首席執(zhí)行官的潘偉迪(Vikram Pandit)判斷如何收縮銀行規(guī)模。

她策劃了將花旗日本證券業(yè)務(wù)出售給三井住友金融集團(tuán)的交易,作價(jià)80億美元。這幫助2009年的花旗獲得了亟需的資本金。除此之外,她還為花旗將美邦經(jīng)紀(jì)業(yè)務(wù)出售給摩根士丹利打好了基礎(chǔ)。

任職期間,她在18個(gè)月內(nèi)完成了超過25筆交易。在這一過程中花旗出售了價(jià)值近萬億美元的資產(chǎn),裁員10萬人。

弗雷澤回憶稱,那段工作是她作為領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者的重要經(jīng)歷之一。

“當(dāng)你真正能身處其位時(shí),才能切實(shí)了解情況,不會(huì)流于空泛。”10月她告訴我。

“究竟要怎么做,才可以避免讓客戶驅(qū)動(dòng)只是停留在墻上的口號(hào)?你做了哪些戰(zhàn)略決策?及早著手,認(rèn)真應(yīng)對(duì),然后逐漸累積優(yōu)勢(shì)爭(zhēng)取勝利……危機(jī)當(dāng)中的學(xué)習(xí)曲線最陡峭。”

盡管并購(gòu)業(yè)務(wù)的經(jīng)歷很有價(jià)值,弗雷澤還是想實(shí)際經(jīng)營(yíng)企業(yè)。

2009年,潘偉迪給了她機(jī)會(huì),讓她回倫敦工作四年,擔(dān)任花旗私人銀行負(fù)責(zé)人,為花旗最富裕的客戶提供服務(wù)。這份工作相當(dāng)吸引人,尤其是與接下來在圣路易斯擔(dān)任花旗抵押貸款公司的首席執(zhí)行官相比。

2013年她接手該工作,而這段經(jīng)歷正如她在2016年演講中所承認(rèn)的,當(dāng)時(shí)的抵押貸款業(yè)務(wù)如同次貸危機(jī)后的“地球劫難”。在她執(zhí)掌下,花旗經(jīng)歷了緩慢而痛苦的恢復(fù)過程,主要因?yàn)槎嗄昵盎ㄆ煸?jīng)向房利美和房地美出售不良抵押貸款,并為處理索賠支付了數(shù)億美元。

2015年,高沛德任命弗雷澤為花旗拉丁美洲業(yè)務(wù)首席執(zhí)行官,她再次獲得機(jī)會(huì)力挽狂瀾。

按凈收入計(jì)算,拉丁美洲在花旗地區(qū)分部中規(guī)模最小但利潤(rùn)率最高,如同皇冠上的寶石。

花旗在墨西哥的零售部門,當(dāng)時(shí)被稱為墨西哥國(guó)家銀行或Banamex,是墨西哥最大的銀行之一,分行達(dá)1400家,占花旗全球?qū)嶓w分支機(jī)構(gòu)一半以上。

在弗雷澤接手時(shí),該業(yè)務(wù)深陷泥潭。

2014年2月,花旗披露稱石油服務(wù)公司Oceanografía涉嫌從Banamex騙取了4億美元。幾個(gè)月后,Banamex發(fā)現(xiàn)某個(gè)為高管提供安全保障的部門員工向外部提供未經(jīng)授權(quán)的服務(wù),且從事非法活動(dòng),因此隨后解散了該部門。

2017年,在接受《美國(guó)銀行家》雜志采訪時(shí),弗雷澤談到要改變花旗在拉丁美洲的文化,不能再讓員工“對(duì)問題惡化視若不見,而是要主動(dòng)提出,‘我對(duì)老板的做法感到不安。’”

這項(xiàng)工作很重要一步就是讓員工相信,舉報(bào)不當(dāng)行為之后,銀行確實(shí)會(huì)采取對(duì)應(yīng)行動(dòng)。

“這很大程度上取決于信任。”她說。人們必須相信“他們提出問題不會(huì)惹禍上身,且公司會(huì)采取措施處理。”

終極清理 (弗雷澤以整頓花旗集團(tuán)聞名。她就任首席執(zhí)行官后,接手的銀行多年年來一直落后于主要競(jìng)爭(zhēng)對(duì)手,漲幅也低于標(biāo)普銀行指數(shù)。) 來源:標(biāo)準(zhǔn)普爾全球

弗雷澤出任拉美業(yè)務(wù)首席執(zhí)行官后,拉美分部還出售了巴西、阿根廷和哥倫比亞等國(guó)的消費(fèi)銀行和信用卡業(yè)務(wù),更專注于當(dāng)?shù)貦C(jī)構(gòu)業(yè)務(wù)。

與此同時(shí),花旗向墨西哥注入了10億美元,墨西哥是拉美國(guó)家當(dāng)中唯一仍然有零售業(yè)務(wù)的國(guó)家。

2016年,花旗宣布了為期四年的投資,主要通過升級(jí)自動(dòng)柜員機(jī)、提供新型數(shù)字工具和分行改造來提升客戶體驗(yàn)。

弗雷澤任職期間,拉丁美洲分部的凈收入和凈利潤(rùn)分別增長(zhǎng)了8%和38%。

弗雷澤在這之后一次升職是在2019年10月,出任全球消費(fèi)者銀行總裁兼首席執(zhí)行官。這也表明她在拉美分公司的工作受到首肯,從而邁上新臺(tái)階。

從同事們口中透露出的跡象也可證實(shí),弗雷澤是高沛德的繼承人。

“消費(fèi)業(yè)務(wù)占收入一半,也是直線經(jīng)營(yíng)業(yè)務(wù),現(xiàn)在都交給了她,還讓她當(dāng)這塊業(yè)務(wù)的總裁,這就是準(zhǔn)備讓她當(dāng)首席執(zhí)行官。”花旗集團(tuán)主席約翰·杜根說。

不過花旗正式任命弗雷澤為首席執(zhí)行官的時(shí)間比預(yù)期的要快。

弗雷澤被任命為總裁時(shí),高沛德曾經(jīng)表示他還要在花旗工作“幾年”,然而11個(gè)月后,公司便宣布二號(hào)人物上位。

在領(lǐng)英的一篇帖子中,高沛德自稱“堅(jiān)決支持任期限制”。

杜根說,高沛德一直計(jì)劃2021年離任,但如今決定將時(shí)間提前,以便弗雷澤能夠“實(shí)際掌控”花旗改善控制和風(fēng)險(xiǎn)流程的進(jìn)度。

時(shí)間表的提前也給了花旗董事會(huì)領(lǐng)先優(yōu)勢(shì),使其成為了華爾街首家提名女性首席執(zhí)行官的大銀行。

“我們很高興能夠率先實(shí)現(xiàn)突破,也很高興公司里有極為適合這份工作的候選人。”杜根說。

從很多方面看,弗雷澤強(qiáng)悍的簡(jiǎn)歷與以前大型銀行的首席執(zhí)行官有相似之處,但她對(duì)工作的態(tài)度卻并不一定符合過往領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者的模式。

很多首席執(zhí)行官都不愿承認(rèn)自我懷疑的存在,她似乎不怕談起。

她說,獲得擔(dān)任全球戰(zhàn)略與并購(gòu)主管的第一反應(yīng)是,憑自己的能力難以勝任。

后來還是一位朋友說服了她:“你為什么擔(dān)心失敗?盡力試試。就算失敗又有什么關(guān)系?”

弗雷澤愿意談?wù)摴ぷ髦腥诵曰囊幻妫瑹o論是缺乏自信、為人父母的壓力,亦或是銀行文化過往的失敗。她不僅在華爾街同輩中鶴立雞群,就算與其他在各自行業(yè)中“登頂”的女性相比也毫不遜色。

有些女性會(huì)擔(dān)心,如果公開這類想法,會(huì)容易被貼上女首席執(zhí)行官的標(biāo)簽。而弗雷澤則認(rèn)為這種坦誠(chéng)是優(yōu)勢(shì):“在某些方面,我可能更容易受到傷害,我的一些男性同事不太愿意談?wù)撨@一問題的人性層面。”5月她告訴我,“這不代表軟弱或無力,我認(rèn)為這會(huì)使我更強(qiáng)大。”

在被派往拉丁美洲之前,弗雷澤曾接替現(xiàn)已退休的塞西莉亞·斯圖爾特?fù)?dān)任花旗美國(guó)消費(fèi)者和商業(yè)銀行首席執(zhí)行官。領(lǐng)導(dǎo)層交接期間,兩人會(huì)見了全國(guó)各地的銀行家。

斯圖爾特回憶說,弗雷澤可以“很自然地坐下來和別人交談,而且不論工作上還是生活上都可以迅速建立聯(lián)系。”

“不管是男性還是女性,擁有飽含如此同理心的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)風(fēng)格,能夠坦誠(chéng)地討論各種情況非常重要。”斯圖爾特說。

這種領(lǐng)導(dǎo)風(fēng)格尤其適合應(yīng)對(duì)疫情。“對(duì)美國(guó)企業(yè)界來說,2021年和2022年可能截然不同。”斯圖爾特表示,“因此,花旗能有這樣一位靈活,并愿意以開放心態(tài)領(lǐng)導(dǎo)公司經(jīng)歷變革的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)人,無論結(jié)果怎樣,都是好事。”

當(dāng)然,打破這層隱形天花板只是開始。這位大型銀行圈子里的首位女首席執(zhí)行官所接手的并非是一臺(tái)運(yùn)轉(zhuǎn)良好的機(jī)器。

花旗任命弗雷澤為首席執(zhí)行官后不到一個(gè)月,美聯(lián)儲(chǔ)和美國(guó)貨幣監(jiān)理署均指責(zé)該行風(fēng)險(xiǎn)控制長(zhǎng)期存在缺陷,為此花旗同意支付4億美元。

而在此前的8月,花旗集團(tuán)曾經(jīng)向Revlon lenders誤匯了9億美元,約為正確金額的100倍。

根據(jù)貨幣監(jiān)理署的指令,監(jiān)管方面有權(quán)否決花旗的重大收購(gòu),必要時(shí)還可以強(qiáng)制要求花旗高管團(tuán)隊(duì)或董事會(huì)變更。

監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)“一般不會(huì)如此嚴(yán)厲,除非真被惹怒,”喬治·華盛頓大學(xué)的法學(xué)教授,曾經(jīng)研究銀行監(jiān)管的亞瑟·威爾馬思表示。

花旗在一份聲明中表示,對(duì)于未能達(dá)到監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)的預(yù)期深表失望,“正實(shí)施深層整改”。

投資者也渴望弗雷澤能夠解決花旗的盈利能力問題。因?yàn)殚L(zhǎng)期以來,花旗一直落后于華爾街的其他競(jìng)爭(zhēng)對(duì)手。

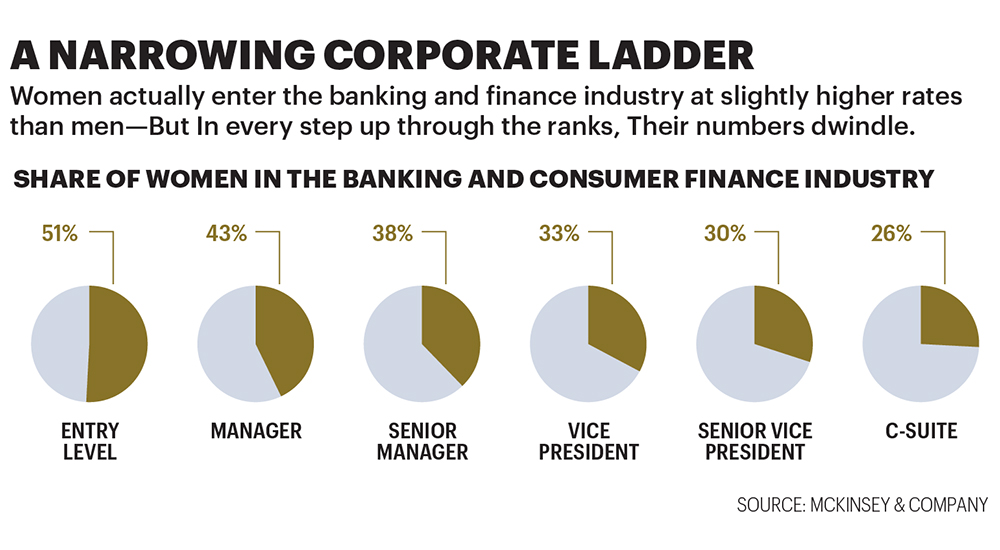

企業(yè)內(nèi)晉升階梯越來越窄 (實(shí)際上,進(jìn)入銀行業(yè)和金融業(yè)的女性比例略高于男性,但每一次晉升過程中,女性人數(shù)都在減少。) 來源:麥肯錫公司

此外,另一大挑戰(zhàn)是對(duì)花旗的控制。

“當(dāng)前正面臨疫情和經(jīng)濟(jì)衰退夾擊。貸款損失將上升,利率也處于歷史低位。”巴克萊銀行的分析師杰森·戈德伯格表示。可以說,現(xiàn)在對(duì)銀行家來說,是非常艱難的時(shí)期。

監(jiān)管舉措對(duì)花旗來說是一記重拳,但威爾馬思認(rèn)為,從某種程度上說,這其實(shí)鞏固了弗雷澤的地位。這種情況下,“如果沒有監(jiān)管者默許,我懷疑她很難順利晉升。”威爾馬思說。(花旗對(duì)此拒絕置評(píng)。)

戈德伯格說,從弗雷澤的過往經(jīng)歷來看,她確實(shí)適合此時(shí)上任。花旗“需要一些調(diào)整,”他指出,“她在清理業(yè)務(wù)和扭轉(zhuǎn)局面方面經(jīng)驗(yàn)豐富。”

弗雷澤在10月的談話中也對(duì)此表示了認(rèn)同。

面對(duì)任何危機(jī),“都要回過頭來說:‘出現(xiàn)問題的根本原因是什么,如何將危局變成機(jī)會(huì),真正實(shí)現(xiàn)跨越式發(fā)展,推動(dòng)銀行邁上新臺(tái)階?’”弗雷澤說。“如何激勵(lì)公司朝著正確的方向努力?我在私人銀行成功過,在抵押貸款部門成功過,在墨西哥也成功過。現(xiàn)在有機(jī)會(huì)能帶領(lǐng)花旗,我對(duì)此感到很興奮。”

今年9月,弗雷澤成了第一位獲得華爾街首席執(zhí)行官職位的女性。到了明年2月,她將正式成為花旗掌門人。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

本文另一版本登載于《財(cái)富》雜志2020年11月刊,標(biāo)題為《華爾街第一女性》。

譯者:夏林

編輯:徐曉彤

CEOs of seven of the largest U.S. banks appeared before the House Financial Services Committee in April 2019. When the panel—all men, all white—were asked under oath if their successors were likely to be female or a person of color, no one raised his hand.

Without saying a word, the CEOs had put a fine point on a hard truth: Wall Street had never had a female CEO, nor was one likely in the near future.

The message they sent was antithetical to the mood of corporate America at the time. The #MeToo movement had prompted a harsh reexamination of office workplace dynamics; institutional investors were demanding that boards of directors add more women; and companies—banks included—were preaching the merits of diversity.

The moment left such a bleak impression that Fortune dedicated pages of its 2019 Most Powerful Women issue to asking three pressing questions: Why had bank CEO suites remained so impenetrable to women? Who might be the first to break through? And when?

We now have a definitive answer to those last two questions: Citigroup in mid-September announced that Jane Fraser would succeed Michael Corbat as chief executive in February. Barring something unforeseeable, Wall Street banks’ long-standing glass ceiling is history.

But Fraser’s appointment doesn’t eliminate the culture that had kept women out of the corner office for so long. In fact, it raises a new set of questions: Who is the woman who will be the first female CEO of a big Wall Street bank and how did she achieve what has, for so long, appeared unachievable?

On one hand, the most recent stage of Fraser’s career follows what Jane Stevenson, head of CEO succession at executive recruiter Korn Ferry, calls “the blueprint”: She worked her way through key business units at the bank and left each better than she found it. Yet at the same time, her refusal to sacrifice her personal life at the altar of her career flouts many of the old “rules” for getting to the top. That ability to find a middle way—to forge a new path through a very old maze—may indeed be an essential part of what makes her uniquely qualified for the job she’ll step into next year. And so, for that matter, is her willingness to talk candidly about navigating the labyrinth.

*****

Fraser, 53, was born in St. Andrews, Scotland. (Yes, as a matter of birth she has an affinity for golf.) She moved to Australia for high school and with aspirations to be a doctor. But she soon learned she was bad at biology but fond of math and economics, which made banking a natural career fit.

From the University of Cambridge, she landed at Goldman Sachs in London at the tender age of 20. She would lament years later that she was “the boring British girl” in the office. “Everyone else was much more exotic, from all over Europe. They were a little bit older, they spoke multiple languages, and I just thought they were so much more interesting than I was,” she said in a 2016 address to the Americas Society and Council of the Americas. The feeling was motivation enough for her to leave London for Madrid, where she spent two years as an analyst at consultancy Asesores Bursátiles and worked on her Spanish—a skill that would prove especially useful years down the line.

After business school at Harvard in the early 1990s, her career diverged further from the typical banking trajectory. Rather than return to a place like Goldman, she opted to join consulting firm McKinsey for a reason she doesn’t sugarcoat: The women she saw in the banking industry at that time “were rather scary,” she said in the 2016 speech.

Those were the days of big shoulder pads and manly suits. The women and many of the men didn’t seem “that happy,” she recalled. “They were very successful. They were brilliant. But it was tough.”

In short: She wanted a life.

Working at McKinsey was still demanding, but it offered the same dynamic—being a trusted adviser to a client—with more predictability.

She got married two years later and got pregnant the same year she was up for partner. “I got quite a lot of advice, ‘Don’t get pregnant in your partnership year.’ And I just thought that was nonsense,” she told me at Fortune’s Most Powerful Women Summit in October. The firm informed her she’d made partner two weeks after she gave birth.

After that moment—having a baby, making partner—she did heed a different piece of advice: “I remember one of my mentors saying to me, ‘You’re going to have several careers in your life, and your careers are going to be measured in decades. So why this sense of rush and trying to have everything at the same time?’?” It led her to make a decision that she says was critical: She chose to work the entirety of her five-year partnership—until she left McKinsey for Citi in 2004—part-time.

“It wasn’t easy—my own ego suffered a bit on that one, because you do see people who are more junior than you who are accelerating faster in their careers,” she said. “But that’s what enabled me to actually feel happy and have a balance in my professional life and personal life.”

That experience changed her perspective—and changed how she operated at the office.

“When I got back to working again and working full-time,” Fraser said, “my clients used to tell me, ‘You’re a much more empathetic person; you were just this machine before.’?”

*****

In 2004, Fraser joined Citi as head of client strategy in the bank’s investment and corporate banking division in London. This is the moment she returned to the traditional banking playbook and began tearing through it. Over the next 16 years, she took on a series of jobs at Citi that taught her about different parts of the business, gave her experience leading units that had their own profit and loss statements or P&L, and offered her opportunities to build relationships and a standout reputation within the firm. “Look at her background,” Stevenson says. Fraser’s rotation in and out of jobs was “an artful process that came together over a decade,” she says. “These kinds of roles lend credibility” when boards are weighing succession plans.

It helps, of course, if some of those roles require you to make tough choices or oversee troubled businesses—and if you prove you have what it takes to handle the demands.

After her run in investment and corporate banking, then-CFO Gary Crittenden offered Fraser the job of global head of strategy and M&A in September 2007 as the financial crisis was mounting. She took the job and relocated to New York to help then-CEO Vikram Pandit decide how to shrink the bank. She orchestrated the sale of Citi’s Japanese securities business to Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group in a $8 billion deal that gave the bank a vital capital boost in 2009. She also laid the groundwork for Citi’s sale of its Smith Barney brokerage to Morgan Stanley. During her time in the role, she executed more than 25 deals in 18 months. The bank sold nearly a trillion dollars’ worth of assets and cut 100,000 jobs in the process.

Fraser recalls that work as one of her foundational experiences as a leader. “It does make you sit there and be more definitive and less wishy-washy,” she told me in October. “What does being client-driven really mean so it’s not just a plaque on the wall? What are some of the strategic choices you make? Do them early and do them well and stack them up to win...Nothing like a crisis to have your steepest learning curve.”

Valuable as the experience was, Fraser still wanted to run a business. Pandit gave her that chance in 2009, sending her back to London for four years to cater to Citi’s wealthiest clients as head of the private bank. It was a sexy job, especially compared with what came next: serving as CEO of CitiMortgage in St. Louis. She took that job in 2013, when the mortgage business was, as she admitted in the 2016 speech, “the scourge of the earth” following the subprime crisis. She oversaw the slow and painful process of righting the ship, as Citi paid hundreds of millions of dollars to settle claims that it had sold faulty mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac years earlier.

Then, in 2015, Fraser got yet another turnaround job, when Corbat named her CEO of Citi’s Latin America business.

Latin America is the smallest of Citi’s regional divisions by net revenue but has the highest rate of return, making it something of a crown jewel. Its retail arm in Mexico, then known as Banco Nacional de México or Banamex, is one of Mexico’s biggest banks, and its 1,400 branches account for more than half of Citi’s physical locations globally.

When Fraser took over, the division was tarnished. In February 2014, Citi disclosed that oil services firm Oceanografía had allegedly defrauded Banamex out of $400 million. Months later, Banamex disbanded a unit of the bank that provided security to executives after discovering that employees had engaged in illegal activity by offering unauthorized services to outside parties.

In a 2017 interview with American Banker, Fraser talked about trying to change the bank’s culture in Latin America so employees would be “more comfortable escalating issues, or saying, ‘I’m not comfortable with what my boss [has] done.’?” A big part of that effort was convincing employees that the bank would act on allegations of wrongdoing. “A lot of this comes down to trust,” she said. People must believe that “if they raise an issue they’re going to be okay, and you will do something about it.”

With Fraser as CEO, the Latin American division also sold off consumer banking and credit card operations in countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia to more narrowly focus on its institutional business in the region.

At the same time, Citi poured $1 billion into Mexico, the only Latin American country where it still has retail operations. The four-year investment, announced in 2016, was intended to upgrade the customer experience with new ATMs, new digital tools, and branch makeovers.

During Fraser’s tenure, net revenue and net profit for the Latin America division grew 8% and 38%, respectively.

Fraser’s next promotion, in October 2019, to president and CEO of global consumer banking, was an indication that the work she’d done in Latin America had pushed her to the next level. It was confirmation of what colleagues say was already obvious: that Fraser was Corbat’s heir apparent. “Giving her the consumer business, which is half of our revenues and a line operating business, and making her president was?…?to tee her up to get ready to be CEO,” Citi chair John Dugan says.

But Citi officially launched Fraser into the top job sooner than expected. When Fraser was named president, Corbat indicated he had “years” left at Citi, but his No. 2 got the nod 11 months later.

Corbat called himself “a steadfast believer in term limits” in explaining the timing in a LinkedIn post. Dugan says Corbat had always planned to leave in 2021 but decided to depart on the early side so Fraser could “own” the bank’s efforts to improve controls and risk processes.

The accelerated timeline also gave Citi an advantage that wasn’t lost on the board—it got to be first to name a female CEO. “We were delighted to beat everyone to the punch. It was going to happen, and we were delighted to have a candidate who was so eminently qualified for the job,” Dugan says.

*****

While Fraser’s ironclad résumé looks, in many ways, like that of the big bank CEOs who’ve come before her, her personal approach to her work doesn’t always conform to the corner office mold.

She’s appeared unafraid of sharing the moments of self-doubt that so many CEOs seem to hide away in the backs of their custom closets. She says her initial response to being offered the global head of strategy and M&A was that she wasn’t good enough for the role. She recalls a friend convinced her, saying, “Why are you worried about failing? Go for it. What does it matter if that’s the case?”

Fraser’s willingness to talk about the human side of the job—whether lapses in self-assuredness, the demands of parenthood, the past failings of bank culture—sets her apart not just from her Wall Street peers, but from other women who have achieved “firsts” in their industries, some of whom fear that by being open about such things they’ll be pigeonholed by the label, female CEO. Fraser sees it as an advantage: “I can be more vulnerable in certain areas; talking more about the human dimensions of this than some of my male colleagues are comfortable [with],” she told me in May. “I don’t feel that’s in any way soft or weaker; I actually think it’s much more powerful.”

Before her posting to Latin America, Fraser succeeded Cecelia Stewart, now retired, for a stint as CEO of Citi’s U.S. consumer and commercial bank. As part of the leadership transition, the pair met with bankers across the country. Stewart recalls Fraser could “just naturally sit down and talk with someone and connect with them, whether it was work-related or life-related.”

“For a person—male or female—to have that level of compassion in their leadership style and that openness and willingness to discuss all different types of situations is critically important,” Stewart says. The approach is especially well suited for the pandemic. “2021 and 2022 for corporate America may look really different,” Stewart says, “so having a leader like Jane who is flexible, who is willing and open to lead through that kind of change, whatever that turns out to be, is terrific and a positive for Citi.”

*****

Breaking the glass ceiling, of course, was just the beginning. Big banking’s first female CEO is not inheriting a well-oiled machine.

Less than a month after Citi named Fraser its next CEO, Citi agreed to pay $400 million after the Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency reprimanded the bank for long-standing deficiencies related to its risk controls. The action followed an embarrassing episode in August in which Citi erroneously sent $900 million to Revlon lenders, roughly 100 times as much as they were supposed to receive. The OCC order gives the regulator veto power over any major Citi acquisition and, if necessary, the right to mandate changes to the bank’s senior management team or board.

It is “not typical” for the regulators to “come down so hard unless they’re really not happy,” says Arthur Wilmarth, a George Washington University law professor who has studied bank regulation. In a statement, Citi said it was disappointed to have fallen short of the regulators’ expectations and has “significant remediation projects underway.”

Investors are also eager for Fraser to address Citi’s profitability, which has long trailed that of its Wall Street rivals.

Another challenge is more out of Citi’s control. “We’re in the middle of a pandemic and recession. Loan losses are going to go up, and interest rates are at historic lows,” says Barclays analyst Jason Goldberg. Fundamentally, it’s a hard time to be a banker.

The regulatory action was a sucker punch to Citi, but Wilmarth argues that, in a way, it actually bolsters Fraser’s position. Under the circumstances, “I doubt that she would’ve gotten the job without the implicit blessing of the regulators,” Wilmarth says. (Citi declined to comment.)

Goldberg says Fraser’s track record means she’s well suited to meet the moment. Citi “is in need of some retooling,” he notes. “She has a lot of experience cleaning things up and turning things around.”

Fraser echoes that point in conversation in October. In the face of any crisis, “I think it’s going back and saying, ‘What are some of the root causes and then how do you turn that into an opportunity to really leapfrog and take the bank to a different level?’?” Fraser says. “And then how do you galvanize the organization to work toward that? I did that with the private bank, did that with mortgages, did that in Mexico. And I’m excited to do it here too.”

In September, Fraser was the first woman to get a Wall Street CEO job. Come February, she’ll be the first one to do the work.?

A version of this article appears in the November 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline, “The first lady of Wall Street.”