幾年前,一位娛樂(lè)行業(yè)的客戶找到馬庫(kù)斯·霍姆斯特姆和他位于斯德哥爾摩的游戲工作室Gang Sweden,委托其為Roblox平臺(tái)創(chuàng)建一些內(nèi)容。Roblox平臺(tái)是一個(gè)元宇宙風(fēng)格的游戲和娛樂(lè)合集,使用方塊圖像,很受孩子們歡迎。

這次任務(wù)聽起來(lái)毫無(wú)難度:霍姆斯特姆團(tuán)隊(duì)的成員在所謂的3A游戲制作方面擁有許多經(jīng)驗(yàn),有些人曾參與過(guò)一些主流游戲大作的開發(fā),例如《重返德軍總部》(Return to Castle Wolfenstein)和《戰(zhàn)錘:末世鼠疫》(Warhammer: Vermintide)等,而Roblox上的很多內(nèi)容都是由該平臺(tái)自己的社區(qū)打造。霍姆斯特姆回憶道:“我們以為會(huì)非常順利,因?yàn)楦?jìng)爭(zhēng)很少。”

結(jié)果卻大相徑庭。霍姆斯特姆承認(rèn):“項(xiàng)目徹底失敗。沒(méi)有人喜歡我們的游戲。”Gang Sweden通過(guò)這次慘痛教訓(xùn)了解到,Roblox是一個(gè)奇特的平臺(tái)。

對(duì)于新手而言,該工作室的游戲主要以目標(biāo)和競(jìng)爭(zhēng)為導(dǎo)向,就像是一款純粹的游戲。但許多青少年用戶使用Roblox平臺(tái)是為了社交,幾乎將其當(dāng)成了社交網(wǎng)絡(luò);事實(shí)證明,許多人在元宇宙中隨意游蕩。與此同時(shí),Gang的游戲卻很復(fù)雜,許多內(nèi)容需要用戶自己探索。但Roblox的年輕用戶更喜歡根據(jù)清晰的指令和活動(dòng),親手創(chuàng)建內(nèi)容。該游戲工作室意識(shí)到,Roblox的受眾之所以使用該平臺(tái),是因?yàn)樗軡M足用戶的期待。

而且這批受眾不容忽視:2022年第1季度,平均每天有5,410萬(wàn)名活躍用戶,在該平臺(tái)共花費(fèi)了118億個(gè)小時(shí)。許多人花費(fèi)用美元購(gòu)買的平臺(tái)貨幣Robux,獲取體驗(yàn)和數(shù)字物品,用于個(gè)性化改造自己的虛擬形象或虛擬居住空間。最值得關(guān)注的是,有超過(guò)1,000萬(wàn)Roblox用戶曾為其他用戶創(chuàng)建體驗(yàn)和游戲,事實(shí)上這類用戶的數(shù)量接近3,000萬(wàn)。許多用戶通過(guò)自己的作品獲得收入,2021年創(chuàng)作者的收入總計(jì)達(dá)到5.38億美元。雖然他們大都是在平臺(tái)上成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的年輕人,但這些用戶/開發(fā)者對(duì)于Roblox生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的重要性不容忽視。他們實(shí)際上就是生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的組成部分。

雖然Roblox在社區(qū)培養(yǎng)方面取得了令人矚目的成果,但該公司依舊未能實(shí)現(xiàn)盈利。2021年,該公司收入19.2億美元,虧損約4.9億美元。隨著疫情帶來(lái)的熱潮出現(xiàn)降溫跡象,華爾街對(duì)Roblox的故事失去了熱情;其股價(jià)較11月的最高點(diǎn)下跌超過(guò)一半。

盡管如此,Gang等公司以及大批自主創(chuàng)作者并沒(méi)有因此退縮,他們繼續(xù)在該平臺(tái)上積極創(chuàng)作。事實(shí)上,Roblox的生態(tài)系統(tǒng)變得更加穩(wěn)健:一些獨(dú)立開發(fā)者正在發(fā)展成專業(yè)工作室,而有經(jīng)驗(yàn)的游戲制作商正在成為Roblox專家,并且有些獲得了風(fēng)險(xiǎn)投資。

Gang Sweden目前僅專注于為Roblox平臺(tái)開發(fā)游戲。工作室有67名員工,已經(jīng)開發(fā)了超過(guò)15款游戲,包括每天有數(shù)百萬(wàn)玩家在線的誠(chéng)意大作《強(qiáng)人模擬器》(Strongman Simulator)(在游戲中,用戶進(jìn)入一個(gè)類似于健身房的虛擬環(huán)境,通過(guò)各種動(dòng)作獲取力量和能量分)。其游戲的收入來(lái)源是出售升級(jí)和虛擬服裝與裝備等。公司還會(huì)為客戶創(chuàng)建定制環(huán)境,如Vans和超級(jí)跑車制造商邁凱倫(McLaren)等。

還有許多工作室在該平臺(tái)上也采取了類似模式。從Hello Kitty咖啡廳到Chipotle的“玉米餅制作”游戲再到Spotify的“音樂(lè)主題島嶼”以及“古馳小鎮(zhèn)”,這些由品牌商贊助的體驗(yàn)成為該生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的常規(guī)特征。(這種變化也受到了廣告監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)的批評(píng)。)

結(jié)果就是,Gang Sweden成為成功在Roblox上找到盈利途徑的許多第三方之一。霍姆斯特姆表示,Gang Sweden已實(shí)現(xiàn)盈利,收入快速增長(zhǎng)。

問(wèn)題是,Roblox能否也找到盈利的途徑。

Roblox似乎最近才走紅,它在2021年3月上市,但實(shí)際上這家公司成立于2004年。更新鮮的是其當(dāng)前的經(jīng)營(yíng)模式。Roblox的經(jīng)營(yíng)模式經(jīng)過(guò)全面進(jìn)化,致力于鼓勵(lì)第三方開發(fā)者,他們可以是在臥室里業(yè)余創(chuàng)作的富有創(chuàng)意的青少年,也可能是有大量資深游戲業(yè)者的工作室。現(xiàn)在注冊(cè)一個(gè)Roblox賬戶,你會(huì)看到豐富多彩的選擇,幫助你探索其元宇宙。但由Roblox自身創(chuàng)作的選擇幾乎為零。

當(dāng)然你也可以說(shuō)Roblox創(chuàng)造了一切。設(shè)計(jì)恰當(dāng)?shù)臄?shù)字建造工具,制定有效的激勵(lì)措施,積極培養(yǎng)并不斷壯大開發(fā)者社區(qū),本身也是一種創(chuàng)意。而且這個(gè)過(guò)程經(jīng)過(guò)了數(shù)年試驗(yàn)和方向調(diào)整。

Roblox高級(jí)主管兼全球開發(fā)者社區(qū)總監(jiān)賈斯汀·蘇澤表示,最早的Roblox就像是一款“學(xué)習(xí)工具”。作為一款物理模擬器,它吸引了12至14歲“有怪癖的孩子”(蘇澤將其作為一種稱贊),兒童可以通過(guò)其中的數(shù)字模塊創(chuàng)作物品和空間。Roblox嘗試過(guò)廣告模式,但該公司最終認(rèn)為,這種模式與正在成形的用戶社區(qū)格格不入。

相反,Roblox加大了對(duì)社區(qū)的培養(yǎng),并且相信人們會(huì)在元宇宙中消費(fèi)。Roblox實(shí)際上采用了現(xiàn)在已經(jīng)眾所周知的“創(chuàng)作者經(jīng)濟(jì)”模式,開始更積極地鼓勵(lì)開發(fā)者在平臺(tái)上開發(fā)可變現(xiàn)的體驗(yàn),并從中賺取抽成。當(dāng)一名Roblox用戶為其虛擬形象購(gòu)買裝備裝飾虛擬空間時(shí),公司會(huì)收取約30%的“平臺(tái)服務(wù)費(fèi)”。

2015年,Roblox啟動(dòng)了所謂的“加速器”計(jì)劃,通過(guò)新人訓(xùn)練營(yíng)的形式,幫助精心選拔出的開發(fā)者成長(zhǎng)。這些開發(fā)者都誕生于該平臺(tái)。該計(jì)劃目前每年為約40名開發(fā)者提供專業(yè)培訓(xùn),以及與Roblox的工程師和其他內(nèi)部人士直接溝通的渠道。公司最初鼓勵(lì)開發(fā)某些類型的游戲和體驗(yàn),但很快改變策略,開始支持開發(fā)者天馬行空地進(jìn)行創(chuàng)作。蘇澤堅(jiān)稱:“我們只是給開發(fā)者提供一套工具。我們并不關(guān)心他們用它來(lái)蓋房子、造窩棚還是做一只鞋子,這一切都由開發(fā)者自己決定。”(事實(shí)上,Roblox后來(lái)澄清公司對(duì)開發(fā)者有一些限制:公司制定了精心設(shè)計(jì)的社區(qū)指導(dǎo)方針和家長(zhǎng)控制設(shè)置,以保證平臺(tái)對(duì)年輕用戶的安全性和適宜性。)最近,Roblox啟動(dòng)了一項(xiàng)更加開放的“Game Fund”計(jì)劃,將向開發(fā)者發(fā)放資助共計(jì)2,500萬(wàn)美元。

有些加速器計(jì)劃的畢業(yè)生已經(jīng)創(chuàng)辦了自己的工作室。Simple Games的創(chuàng)始人內(nèi)森·克萊門斯就是其中之一。內(nèi)森今年21歲,他的合伙人包括他的兩個(gè)妹妹內(nèi)奧米(18歲)和瑞秋(15歲)以及父母。他們與一個(gè)外包程序員團(tuán)隊(duì)合作,開發(fā)了約15款游戲,包括熱門角色扮演游戲《城市生活》(City Life),總收入達(dá)到小七位數(shù)。(克萊門斯沒(méi)有透露詳細(xì)數(shù)據(jù),但他表示Simple Games向慈善事業(yè)捐款超過(guò)15萬(wàn)美元。)

克萊門斯坦言:“我從來(lái)沒(méi)有把Roblox當(dāng)做游戲。”事實(shí)上,他從來(lái)都不是一名游戲玩家。但他在約14歲的時(shí)候發(fā)現(xiàn)了這個(gè)平臺(tái),更準(zhǔn)確地說(shuō),發(fā)現(xiàn)了Roblox Studio建造工具。當(dāng)時(shí)他使用谷歌SketchUp等程序,已經(jīng)學(xué)會(huì)了3D建模和計(jì)算機(jī)輔助設(shè)計(jì)(CAD)渲染。他可以利用這些技能,通過(guò)開發(fā)Roblox游戲賺錢。后來(lái)他發(fā)現(xiàn)可以與程序員合作開發(fā)自己的游戲。他說(shuō)道:“我們從那時(shí)候才了解到市場(chǎng)規(guī)模之龐大。”

內(nèi)森的父母杰夫和香儂一直在關(guān)注著他,隨著他的事業(yè)不斷壯大,他們開始直接參與,主要負(fù)責(zé)業(yè)務(wù)方面。內(nèi)奧米在15歲時(shí)加入工作室開發(fā)自己的項(xiàng)目;她的最新作品《分層服裝》(Layered Clothing)是一款虛擬化妝比賽游戲,利用了Roblox一項(xiàng)優(yōu)化虛擬形象裝扮結(jié)果的新功能。瑞秋在12歲左右加入工作室。她喜歡數(shù)字藝術(shù),精通Procreate等程序。

內(nèi)森形容參加加速器計(jì)劃的經(jīng)歷對(duì)他具有顛覆性的意義。18歲的時(shí)候,在Roblox的資助下,他在加州用三個(gè)月時(shí)間,通過(guò)課程和報(bào)告,學(xué)習(xí)如何充分利用該平臺(tái),學(xué)習(xí)的內(nèi)容涵蓋了交互設(shè)計(jì)到財(cái)務(wù)等方方面面。他說(shuō):“那段時(shí)間有些混亂,但也讓我覺(jué)得非常神奇。在那之后,我開始全身心投入到Roblox平臺(tái)。”

像內(nèi)森一樣的人大有人在。事實(shí)上,Roblox生態(tài)系統(tǒng)經(jīng)過(guò)許多年循序漸進(jìn)的緩慢成長(zhǎng),在過(guò)去兩年似乎已經(jīng)達(dá)到了創(chuàng)作者經(jīng)濟(jì)公司渴望的良性飛輪效應(yīng):越多人能夠通過(guò)在平臺(tái)上開發(fā)作品維持生計(jì)甚至成為百萬(wàn)富翁,平臺(tái)就能吸引越多用戶;隨著用戶參與度的提升,平臺(tái)對(duì)于開發(fā)者就更有吸引力。目前,Roblox文化的熱度超過(guò)了平臺(tái)上的實(shí)際參與度,有以Roblox為導(dǎo)向的YouTube用戶和出版物,以及Twitch解說(shuō)用戶,公司還舉辦了年度開發(fā)者活動(dòng),幫助創(chuàng)作者拓展人脈,建立新的關(guān)系(達(dá)成更多交易)。

既然如此,為什么Roblox的收入依舊為負(fù)?Roblox首席商務(wù)官克雷格·多納托認(rèn)為,這個(gè)問(wèn)題是錯(cuò)誤的。他說(shuō)道:“我們?cè)趦?nèi)部不會(huì)討論收入和盈利能力。”相反,公司關(guān)注的是“用戶消費(fèi)”和現(xiàn)金流量。當(dāng)用戶購(gòu)買平臺(tái)貨幣Robux時(shí),Roblox可收到現(xiàn)金。(成本取決于用戶購(gòu)買的數(shù)量以及是否選擇“訂閱”服務(wù),但用戶用大約10美元基本可以購(gòu)買800枚Robux。訂閱服務(wù)會(huì)每個(gè)月為用戶發(fā)送新的Robux賬單。)

用戶通常會(huì)用這些Robux購(gòu)買體驗(yàn)或虛擬物品,收入被分?jǐn)偟接脩糍?gòu)買物品的整個(gè)生命周期;例如一件虛擬襯衫的價(jià)格可能在25個(gè)月里進(jìn)行攤銷。多納托表示,結(jié)果就是雖然這種收入增長(zhǎng)緩慢,但公司實(shí)現(xiàn)了正向現(xiàn)金流:“我們銀行賬戶里的資金在不斷增多而不是減少。”

質(zhì)疑者提到了自疫情封鎖逐步解除以來(lái),Roblox數(shù)據(jù)的不斷下滑:總預(yù)估用戶消費(fèi)較一年前下降了兩個(gè)百分點(diǎn),用戶平均消費(fèi)額也有所下滑。分析師下調(diào)了對(duì)該公司的收入預(yù)估,甚至有人公開表示看跌該公司。例如,高盛(Goldman Sachs)分析師埃里克·謝里登最近將對(duì)該公司股票的前景評(píng)級(jí)從買入下調(diào)至中立,認(rèn)為公司短期內(nèi)存在用戶增長(zhǎng)持續(xù)放緩的可能;美國(guó)銀行(Bank of America)分析師奧馬爾·德蘇基最近大幅下調(diào)了Roblox股票的目標(biāo)價(jià)位。

但Roblox似乎認(rèn)為疫情期間的大幅增長(zhǎng)和后續(xù)的降溫是公司增長(zhǎng)過(guò)程中的反常時(shí)刻。而且沒(méi)有任何跡象表明公司將改變竭盡所能促進(jìn)增長(zhǎng)的策略,例如投資平臺(tái)、擴(kuò)充服務(wù)器以及不多擴(kuò)大對(duì)創(chuàng)作者/內(nèi)容的飛輪效應(yīng)等,這也是最重要的一點(diǎn)。公司真正的想法是,最終有足夠多的用戶在平臺(tái)上進(jìn)行足夠多的消費(fèi),使“用戶消費(fèi)”帶來(lái)的收入能夠超過(guò)平臺(tái)擴(kuò)張和維護(hù)的成本,從而實(shí)現(xiàn)傳統(tǒng)意義上的盈利。(就連一些Roblox的華爾街批評(píng)者也看好公司的長(zhǎng)期前景,尤其是對(duì)于堅(jiān)信元宇宙潛力的人而言。)

在這方面,該公司有兩條策略尤其值得關(guān)注。一條策略是在2019年推出的“基于參與度”向開發(fā)者付費(fèi)的模式。新手創(chuàng)作者可能需要時(shí)間積累足夠多的受眾,才能真正將一款游戲或一種體驗(yàn)變現(xiàn)。而基于參與度的付費(fèi)可以作為對(duì)創(chuàng)作者的激勵(lì),或者權(quán)宜之計(jì)。開發(fā)者甚至不需要主動(dòng)爭(zhēng)取,資金會(huì)自動(dòng)出現(xiàn)在他們的Robux賬戶中。多納托表示:“我們希望開發(fā)者能夠憑借投入的時(shí)間獲得收入。”2021年,Roblox共發(fā)放了8,610萬(wàn)美元的參與度付費(fèi),約占向開發(fā)者付費(fèi)總額的16%。

其次,Roblox對(duì)于平臺(tái)上的品牌滲透,似乎選擇了一種中立的態(tài)度。這是非常驚人的,因?yàn)槠放茲B透不僅實(shí)實(shí)在在發(fā)生了,而且其發(fā)生的頻率和覆蓋范圍將不斷擴(kuò)大,并將有更大的變現(xiàn)潛力。但Roblox目前似乎并不打算直接與品牌商合作;相反,公司鼓勵(lì)品牌商與開發(fā)者合作,無(wú)論是像克萊門斯家族一樣從平臺(tái)上成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的開發(fā)者,還是Gang這樣的外部專業(yè)開發(fā)者。

多納托表示,讓這種動(dòng)態(tài)在生態(tài)系統(tǒng)內(nèi)自由發(fā)揮,使品牌體驗(yàn)根據(jù)自身的優(yōu)缺點(diǎn)經(jīng)歷起起落落,比建立更直接的合作伙伴關(guān)系更容易。事實(shí)上,作為開發(fā)者負(fù)責(zé)人的蘇澤表示,《收養(yǎng)我吧》(Adopt Me)(Roblox上最熱門的游戲之一,玩家在游戲中可以照顧和交換虛擬寵物)這款游戲中有許多與迪士尼(Disney)有關(guān)的品牌“植入”。他表示,Roblox更喜歡這種模式,即有品牌參與,但公司不擔(dān)任直接中間人。多納托也表示:“我們只是努力創(chuàng)建一個(gè)公平的競(jìng)爭(zhēng)環(huán)境。”

公司還有第三條策略,雖然到目前為止產(chǎn)生的影響較小,但可能對(duì)Roblox的未來(lái)具有至關(guān)重要的意義。蘇澤指出,Roblox用戶的平均年齡正在慢慢小幅增長(zhǎng):52%的用戶目前超過(guò)13歲。等著用戶年齡增長(zhǎng),或者蘇澤所說(shuō)的“年齡不可知論”,成為公司的目標(biāo)。然后公司可以鼓勵(lì)用戶嘗試瑜伽空間等,或者現(xiàn)實(shí)的旅行導(dǎo)向體驗(yàn)。甚至演唱會(huì)和DJ表演等數(shù)字活動(dòng)也能吸引年齡稍大的青少年用戶。(公司表示17至24歲的年輕人是增長(zhǎng)最快的用戶群體。)

公司重視這一點(diǎn)的理由顯而易見:作為一家公司,Roblox依賴用戶消費(fèi),而要依靠?jī)和鼙妼?shí)現(xiàn)這個(gè)目標(biāo)是一項(xiàng)復(fù)雜的挑戰(zhàn)。未成年用戶需要父母參與注冊(cè)Robux賬戶,但除此之外,成年人的監(jiān)督參差不齊,留下了發(fā)生可疑交易的可能性。4月,非營(yíng)利組織廣告中的真相(Truth In Advertising)向聯(lián)邦貿(mào)易委員會(huì)(Federal Trade Commission)投訴,指責(zé)Roblox“通過(guò)多種方式允許將廣告與有機(jī)內(nèi)容秘密關(guān)聯(lián)。”與此同時(shí),該平臺(tái)在最近的一次流行文化事件中似乎扮演了不幸的角色。金·卡戴珊6歲的兒子最近在Roblox上偶然發(fā)現(xiàn)的一條內(nèi)容,提到了卡戴珊和前男友的性愛(ài)錄像帶。(據(jù)報(bào)道,該公司刪除了提及這個(gè)錄像帶的“體驗(yàn)”,并封殺了其創(chuàng)作者。)騙人的機(jī)器人程序也是一個(gè)問(wèn)題。Roblox為一項(xiàng)用于發(fā)現(xiàn)假冒虛擬物品的技術(shù)提交了專利申請(qǐng)。

即使是合法銷售也會(huì)引發(fā)人們的擔(dān)憂,因?yàn)殇N售的對(duì)象是未成年消費(fèi)者,他們的大腦尚未發(fā)育完全。有些活動(dòng)有意吸引人們?cè)谠撈脚_(tái)上大量消費(fèi)。據(jù)媒體報(bào)道,Lil Nas X在Roblox上舉辦的一場(chǎng)活動(dòng)的數(shù)字商品銷售額接近1,000萬(wàn)美元。某些稀有物品的價(jià)格高達(dá)數(shù)千枚Robux。這些物品之所以稀有是因?yàn)槠湓谔囟ㄓ螒蛑械膶?shí)用性,或者因?yàn)槠渖矸輪?wèn)題,將其稀缺性與現(xiàn)實(shí)世界的價(jià)值掛鉤。

作家、游戲設(shè)計(jì)師和批評(píng)家以及華盛頓大學(xué)圣路易斯分校(Washington University in St. Louis)傳媒與計(jì)算機(jī)科學(xué)教授伊恩·博格斯特表示:“在Roblox上有很多欺騙消費(fèi)者的機(jī)會(huì),尤其是兒童。”比如迫使消費(fèi)者購(gòu)買“禮物”,或者以低于真實(shí)價(jià)值的價(jià)格賣掉他們的數(shù)字物品等。

但博格斯特發(fā)現(xiàn),從《口袋妖怪》(Pokémon)狂熱到《堡壘之夜》(Fortnite)引發(fā)的擔(dān)憂,這類暴力游戲在家長(zhǎng)當(dāng)中造成的恐慌,并沒(méi)有對(duì)Roblox產(chǎn)生影響。或許這與Roblox方方正正、毫無(wú)威脅甚至有些笨重的審美有關(guān)。博格斯特表示:“或許家長(zhǎng)認(rèn)為:‘它可能不是很重要。因?yàn)橹匾臇|西應(yīng)該看起來(lái)更精致。”

Roblox提到其內(nèi)容審查工作稱,公司在內(nèi)容審查方面付出了大量努力,這也是公司的主要支出項(xiàng)目之一。此外,筆者采訪過(guò)的Roblox高管和開發(fā)者都提到了平臺(tái)的“社區(qū)”環(huán)境,因?yàn)檫@是一個(gè)基本上由用戶創(chuàng)造的世界,維持一個(gè)誠(chéng)信、安全的環(huán)境符合用戶的既得利益。

Roblox最終也需要維持這樣一個(gè)環(huán)境:公司幾乎在所有層面,都將未來(lái)寄托于其培養(yǎng)的生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的創(chuàng)造力、敏銳度和道德原則。對(duì)傳統(tǒng)收益不屑一顧這種策略并不能持久,而且華爾街似乎正在失去耐心。但正如多納托所說(shuō),這家有18年歷史的公司相信,現(xiàn)在強(qiáng)勁的現(xiàn)金流量未來(lái)將演變成利潤(rùn)。“我們才剛剛起步。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

翻譯:劉進(jìn)龍

審校:汪皓

幾年前,一位娛樂(lè)行業(yè)的客戶找到馬庫(kù)斯·霍姆斯特姆和他位于斯德哥爾摩的游戲工作室Gang Sweden,委托其為Roblox平臺(tái)創(chuàng)建一些內(nèi)容。Roblox平臺(tái)是一個(gè)元宇宙風(fēng)格的游戲和娛樂(lè)合集,使用方塊圖像,很受孩子們歡迎。

這次任務(wù)聽起來(lái)毫無(wú)難度:霍姆斯特姆團(tuán)隊(duì)的成員在所謂的3A游戲制作方面擁有許多經(jīng)驗(yàn),有些人曾參與過(guò)一些主流游戲大作的開發(fā),例如《重返德軍總部》(Return to Castle Wolfenstein)和《戰(zhàn)錘:末世鼠疫》(Warhammer: Vermintide)等,而Roblox上的很多內(nèi)容都是由該平臺(tái)自己的社區(qū)打造。霍姆斯特姆回憶道:“我們以為會(huì)非常順利,因?yàn)楦?jìng)爭(zhēng)很少。”

結(jié)果卻大相徑庭。霍姆斯特姆承認(rèn):“項(xiàng)目徹底失敗。沒(méi)有人喜歡我們的游戲。”Gang Sweden通過(guò)這次慘痛教訓(xùn)了解到,Roblox是一個(gè)奇特的平臺(tái)。

對(duì)于新手而言,該工作室的游戲主要以目標(biāo)和競(jìng)爭(zhēng)為導(dǎo)向,就像是一款純粹的游戲。但許多青少年用戶使用Roblox平臺(tái)是為了社交,幾乎將其當(dāng)成了社交網(wǎng)絡(luò);事實(shí)證明,許多人在元宇宙中隨意游蕩。與此同時(shí),Gang的游戲卻很復(fù)雜,許多內(nèi)容需要用戶自己探索。但Roblox的年輕用戶更喜歡根據(jù)清晰的指令和活動(dòng),親手創(chuàng)建內(nèi)容。該游戲工作室意識(shí)到,Roblox的受眾之所以使用該平臺(tái),是因?yàn)樗軡M足用戶的期待。

而且這批受眾不容忽視:2022年第1季度,平均每天有5,410萬(wàn)名活躍用戶,在該平臺(tái)共花費(fèi)了118億個(gè)小時(shí)。許多人花費(fèi)用美元購(gòu)買的平臺(tái)貨幣Robux,獲取體驗(yàn)和數(shù)字物品,用于個(gè)性化改造自己的虛擬形象或虛擬居住空間。最值得關(guān)注的是,有超過(guò)1,000萬(wàn)Roblox用戶曾為其他用戶創(chuàng)建體驗(yàn)和游戲,事實(shí)上這類用戶的數(shù)量接近3,000萬(wàn)。許多用戶通過(guò)自己的作品獲得收入,2021年創(chuàng)作者的收入總計(jì)達(dá)到5.38億美元。雖然他們大都是在平臺(tái)上成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的年輕人,但這些用戶/開發(fā)者對(duì)于Roblox生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的重要性不容忽視。他們實(shí)際上就是生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的組成部分。

雖然Roblox在社區(qū)培養(yǎng)方面取得了令人矚目的成果,但該公司依舊未能實(shí)現(xiàn)盈利。2021年,該公司收入19.2億美元,虧損約4.9億美元。隨著疫情帶來(lái)的熱潮出現(xiàn)降溫跡象,華爾街對(duì)Roblox的故事失去了熱情;其股價(jià)較11月的最高點(diǎn)下跌超過(guò)一半。

盡管如此,Gang等公司以及大批自主創(chuàng)作者并沒(méi)有因此退縮,他們繼續(xù)在該平臺(tái)上積極創(chuàng)作。事實(shí)上,Roblox的生態(tài)系統(tǒng)變得更加穩(wěn)健:一些獨(dú)立開發(fā)者正在發(fā)展成專業(yè)工作室,而有經(jīng)驗(yàn)的游戲制作商正在成為Roblox專家,并且有些獲得了風(fēng)險(xiǎn)投資。

Gang Sweden目前僅專注于為Roblox平臺(tái)開發(fā)游戲。工作室有67名員工,已經(jīng)開發(fā)了超過(guò)15款游戲,包括每天有數(shù)百萬(wàn)玩家在線的誠(chéng)意大作《強(qiáng)人模擬器》(Strongman Simulator)(在游戲中,用戶進(jìn)入一個(gè)類似于健身房的虛擬環(huán)境,通過(guò)各種動(dòng)作獲取力量和能量分)。其游戲的收入來(lái)源是出售升級(jí)和虛擬服裝與裝備等。公司還會(huì)為客戶創(chuàng)建定制環(huán)境,如Vans和超級(jí)跑車制造商邁凱倫(McLaren)等。

還有許多工作室在該平臺(tái)上也采取了類似模式。從Hello Kitty咖啡廳到Chipotle的“玉米餅制作”游戲再到Spotify的“音樂(lè)主題島嶼”以及“古馳小鎮(zhèn)”,這些由品牌商贊助的體驗(yàn)成為該生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的常規(guī)特征。(這種變化也受到了廣告監(jiān)管機(jī)構(gòu)的批評(píng)。)

結(jié)果就是,Gang Sweden成為成功在Roblox上找到盈利途徑的許多第三方之一。霍姆斯特姆表示,Gang Sweden已實(shí)現(xiàn)盈利,收入快速增長(zhǎng)。

問(wèn)題是,Roblox能否也找到盈利的途徑。

Roblox似乎最近才走紅,它在2021年3月上市,但實(shí)際上這家公司成立于2004年。更新鮮的是其當(dāng)前的經(jīng)營(yíng)模式。Roblox的經(jīng)營(yíng)模式經(jīng)過(guò)全面進(jìn)化,致力于鼓勵(lì)第三方開發(fā)者,他們可以是在臥室里業(yè)余創(chuàng)作的富有創(chuàng)意的青少年,也可能是有大量資深游戲業(yè)者的工作室。現(xiàn)在注冊(cè)一個(gè)Roblox賬戶,你會(huì)看到豐富多彩的選擇,幫助你探索其元宇宙。但由Roblox自身創(chuàng)作的選擇幾乎為零。

當(dāng)然你也可以說(shuō)Roblox創(chuàng)造了一切。設(shè)計(jì)恰當(dāng)?shù)臄?shù)字建造工具,制定有效的激勵(lì)措施,積極培養(yǎng)并不斷壯大開發(fā)者社區(qū),本身也是一種創(chuàng)意。而且這個(gè)過(guò)程經(jīng)過(guò)了數(shù)年試驗(yàn)和方向調(diào)整。

Roblox高級(jí)主管兼全球開發(fā)者社區(qū)總監(jiān)賈斯汀·蘇澤表示,最早的Roblox就像是一款“學(xué)習(xí)工具”。作為一款物理模擬器,它吸引了12至14歲“有怪癖的孩子”(蘇澤將其作為一種稱贊),兒童可以通過(guò)其中的數(shù)字模塊創(chuàng)作物品和空間。Roblox嘗試過(guò)廣告模式,但該公司最終認(rèn)為,這種模式與正在成形的用戶社區(qū)格格不入。

相反,Roblox加大了對(duì)社區(qū)的培養(yǎng),并且相信人們會(huì)在元宇宙中消費(fèi)。Roblox實(shí)際上采用了現(xiàn)在已經(jīng)眾所周知的“創(chuàng)作者經(jīng)濟(jì)”模式,開始更積極地鼓勵(lì)開發(fā)者在平臺(tái)上開發(fā)可變現(xiàn)的體驗(yàn),并從中賺取抽成。當(dāng)一名Roblox用戶為其虛擬形象購(gòu)買裝備裝飾虛擬空間時(shí),公司會(huì)收取約30%的“平臺(tái)服務(wù)費(fèi)”。

2015年,Roblox啟動(dòng)了所謂的“加速器”計(jì)劃,通過(guò)新人訓(xùn)練營(yíng)的形式,幫助精心選拔出的開發(fā)者成長(zhǎng)。這些開發(fā)者都誕生于該平臺(tái)。該計(jì)劃目前每年為約40名開發(fā)者提供專業(yè)培訓(xùn),以及與Roblox的工程師和其他內(nèi)部人士直接溝通的渠道。公司最初鼓勵(lì)開發(fā)某些類型的游戲和體驗(yàn),但很快改變策略,開始支持開發(fā)者天馬行空地進(jìn)行創(chuàng)作。蘇澤堅(jiān)稱:“我們只是給開發(fā)者提供一套工具。我們并不關(guān)心他們用它來(lái)蓋房子、造窩棚還是做一只鞋子,這一切都由開發(fā)者自己決定。”(事實(shí)上,Roblox后來(lái)澄清公司對(duì)開發(fā)者有一些限制:公司制定了精心設(shè)計(jì)的社區(qū)指導(dǎo)方針和家長(zhǎng)控制設(shè)置,以保證平臺(tái)對(duì)年輕用戶的安全性和適宜性。)最近,Roblox啟動(dòng)了一項(xiàng)更加開放的“Game Fund”計(jì)劃,將向開發(fā)者發(fā)放資助共計(jì)2,500萬(wàn)美元。

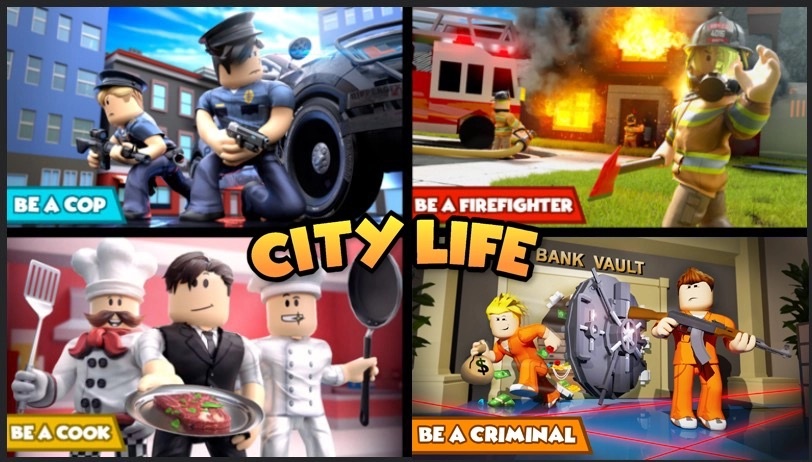

有些加速器計(jì)劃的畢業(yè)生已經(jīng)創(chuàng)辦了自己的工作室。Simple Games的創(chuàng)始人內(nèi)森·克萊門斯就是其中之一。內(nèi)森今年21歲,他的合伙人包括他的兩個(gè)妹妹內(nèi)奧米(18歲)和瑞秋(15歲)以及父母。他們與一個(gè)外包程序員團(tuán)隊(duì)合作,開發(fā)了約15款游戲,包括熱門角色扮演游戲《城市生活》(City Life),總收入達(dá)到小七位數(shù)。(克萊門斯沒(méi)有透露詳細(xì)數(shù)據(jù),但他表示Simple Games向慈善事業(yè)捐款超過(guò)15萬(wàn)美元。)

克萊門斯坦言:“我從來(lái)沒(méi)有把Roblox當(dāng)做游戲。”事實(shí)上,他從來(lái)都不是一名游戲玩家。但他在約14歲的時(shí)候發(fā)現(xiàn)了這個(gè)平臺(tái),更準(zhǔn)確地說(shuō),發(fā)現(xiàn)了Roblox Studio建造工具。當(dāng)時(shí)他使用谷歌SketchUp等程序,已經(jīng)學(xué)會(huì)了3D建模和計(jì)算機(jī)輔助設(shè)計(jì)(CAD)渲染。他可以利用這些技能,通過(guò)開發(fā)Roblox游戲賺錢。后來(lái)他發(fā)現(xiàn)可以與程序員合作開發(fā)自己的游戲。他說(shuō)道:“我們從那時(shí)候才了解到市場(chǎng)規(guī)模之龐大。”

內(nèi)森的父母杰夫和香儂一直在關(guān)注著他,隨著他的事業(yè)不斷壯大,他們開始直接參與,主要負(fù)責(zé)業(yè)務(wù)方面。內(nèi)奧米在15歲時(shí)加入工作室開發(fā)自己的項(xiàng)目;她的最新作品《分層服裝》(Layered Clothing)是一款虛擬化妝比賽游戲,利用了Roblox一項(xiàng)優(yōu)化虛擬形象裝扮結(jié)果的新功能。瑞秋在12歲左右加入工作室。她喜歡數(shù)字藝術(shù),精通Procreate等程序。

內(nèi)森形容參加加速器計(jì)劃的經(jīng)歷對(duì)他具有顛覆性的意義。18歲的時(shí)候,在Roblox的資助下,他在加州用三個(gè)月時(shí)間,通過(guò)課程和報(bào)告,學(xué)習(xí)如何充分利用該平臺(tái),學(xué)習(xí)的內(nèi)容涵蓋了交互設(shè)計(jì)到財(cái)務(wù)等方方面面。他說(shuō):“那段時(shí)間有些混亂,但也讓我覺(jué)得非常神奇。在那之后,我開始全身心投入到Roblox平臺(tái)。”

像內(nèi)森一樣的人大有人在。事實(shí)上,Roblox生態(tài)系統(tǒng)經(jīng)過(guò)許多年循序漸進(jìn)的緩慢成長(zhǎng),在過(guò)去兩年似乎已經(jīng)達(dá)到了創(chuàng)作者經(jīng)濟(jì)公司渴望的良性飛輪效應(yīng):越多人能夠通過(guò)在平臺(tái)上開發(fā)作品維持生計(jì)甚至成為百萬(wàn)富翁,平臺(tái)就能吸引越多用戶;隨著用戶參與度的提升,平臺(tái)對(duì)于開發(fā)者就更有吸引力。目前,Roblox文化的熱度超過(guò)了平臺(tái)上的實(shí)際參與度,有以Roblox為導(dǎo)向的YouTube用戶和出版物,以及Twitch解說(shuō)用戶,公司還舉辦了年度開發(fā)者活動(dòng),幫助創(chuàng)作者拓展人脈,建立新的關(guān)系(達(dá)成更多交易)。

既然如此,為什么Roblox的收入依舊為負(fù)?Roblox首席商務(wù)官克雷格·多納托認(rèn)為,這個(gè)問(wèn)題是錯(cuò)誤的。他說(shuō)道:“我們?cè)趦?nèi)部不會(huì)討論收入和盈利能力。”相反,公司關(guān)注的是“用戶消費(fèi)”和現(xiàn)金流量。當(dāng)用戶購(gòu)買平臺(tái)貨幣Robux時(shí),Roblox可收到現(xiàn)金。(成本取決于用戶購(gòu)買的數(shù)量以及是否選擇“訂閱”服務(wù),但用戶用大約10美元基本可以購(gòu)買800枚Robux。訂閱服務(wù)會(huì)每個(gè)月為用戶發(fā)送新的Robux賬單。)

用戶通常會(huì)用這些Robux購(gòu)買體驗(yàn)或虛擬物品,收入被分?jǐn)偟接脩糍?gòu)買物品的整個(gè)生命周期;例如一件虛擬襯衫的價(jià)格可能在25個(gè)月里進(jìn)行攤銷。多納托表示,結(jié)果就是雖然這種收入增長(zhǎng)緩慢,但公司實(shí)現(xiàn)了正向現(xiàn)金流:“我們銀行賬戶里的資金在不斷增多而不是減少。”

質(zhì)疑者提到了自疫情封鎖逐步解除以來(lái),Roblox數(shù)據(jù)的不斷下滑:總預(yù)估用戶消費(fèi)較一年前下降了兩個(gè)百分點(diǎn),用戶平均消費(fèi)額也有所下滑。分析師下調(diào)了對(duì)該公司的收入預(yù)估,甚至有人公開表示看跌該公司。例如,高盛(Goldman Sachs)分析師埃里克·謝里登最近將對(duì)該公司股票的前景評(píng)級(jí)從買入下調(diào)至中立,認(rèn)為公司短期內(nèi)存在用戶增長(zhǎng)持續(xù)放緩的可能;美國(guó)銀行(Bank of America)分析師奧馬爾·德蘇基最近大幅下調(diào)了Roblox股票的目標(biāo)價(jià)位。

但Roblox似乎認(rèn)為疫情期間的大幅增長(zhǎng)和后續(xù)的降溫是公司增長(zhǎng)過(guò)程中的反常時(shí)刻。而且沒(méi)有任何跡象表明公司將改變竭盡所能促進(jìn)增長(zhǎng)的策略,例如投資平臺(tái)、擴(kuò)充服務(wù)器以及不多擴(kuò)大對(duì)創(chuàng)作者/內(nèi)容的飛輪效應(yīng)等,這也是最重要的一點(diǎn)。公司真正的想法是,最終有足夠多的用戶在平臺(tái)上進(jìn)行足夠多的消費(fèi),使“用戶消費(fèi)”帶來(lái)的收入能夠超過(guò)平臺(tái)擴(kuò)張和維護(hù)的成本,從而實(shí)現(xiàn)傳統(tǒng)意義上的盈利。(就連一些Roblox的華爾街批評(píng)者也看好公司的長(zhǎng)期前景,尤其是對(duì)于堅(jiān)信元宇宙潛力的人而言。)

在這方面,該公司有兩條策略尤其值得關(guān)注。一條策略是在2019年推出的“基于參與度”向開發(fā)者付費(fèi)的模式。新手創(chuàng)作者可能需要時(shí)間積累足夠多的受眾,才能真正將一款游戲或一種體驗(yàn)變現(xiàn)。而基于參與度的付費(fèi)可以作為對(duì)創(chuàng)作者的激勵(lì),或者權(quán)宜之計(jì)。開發(fā)者甚至不需要主動(dòng)爭(zhēng)取,資金會(huì)自動(dòng)出現(xiàn)在他們的Robux賬戶中。多納托表示:“我們希望開發(fā)者能夠憑借投入的時(shí)間獲得收入。”2021年,Roblox共發(fā)放了8,610萬(wàn)美元的參與度付費(fèi),約占向開發(fā)者付費(fèi)總額的16%。

其次,Roblox對(duì)于平臺(tái)上的品牌滲透,似乎選擇了一種中立的態(tài)度。這是非常驚人的,因?yàn)槠放茲B透不僅實(shí)實(shí)在在發(fā)生了,而且其發(fā)生的頻率和覆蓋范圍將不斷擴(kuò)大,并將有更大的變現(xiàn)潛力。但Roblox目前似乎并不打算直接與品牌商合作;相反,公司鼓勵(lì)品牌商與開發(fā)者合作,無(wú)論是像克萊門斯家族一樣從平臺(tái)上成長(zhǎng)起來(lái)的開發(fā)者,還是Gang這樣的外部專業(yè)開發(fā)者。

多納托表示,讓這種動(dòng)態(tài)在生態(tài)系統(tǒng)內(nèi)自由發(fā)揮,使品牌體驗(yàn)根據(jù)自身的優(yōu)缺點(diǎn)經(jīng)歷起起落落,比建立更直接的合作伙伴關(guān)系更容易。事實(shí)上,作為開發(fā)者負(fù)責(zé)人的蘇澤表示,《收養(yǎng)我吧》(Adopt Me)(Roblox上最熱門的游戲之一,玩家在游戲中可以照顧和交換虛擬寵物)這款游戲中有許多與迪士尼(Disney)有關(guān)的品牌“植入”。他表示,Roblox更喜歡這種模式,即有品牌參與,但公司不擔(dān)任直接中間人。多納托也表示:“我們只是努力創(chuàng)建一個(gè)公平的競(jìng)爭(zhēng)環(huán)境。”

公司還有第三條策略,雖然到目前為止產(chǎn)生的影響較小,但可能對(duì)Roblox的未來(lái)具有至關(guān)重要的意義。蘇澤指出,Roblox用戶的平均年齡正在慢慢小幅增長(zhǎng):52%的用戶目前超過(guò)13歲。等著用戶年齡增長(zhǎng),或者蘇澤所說(shuō)的“年齡不可知論”,成為公司的目標(biāo)。然后公司可以鼓勵(lì)用戶嘗試瑜伽空間等,或者現(xiàn)實(shí)的旅行導(dǎo)向體驗(yàn)。甚至演唱會(huì)和DJ表演等數(shù)字活動(dòng)也能吸引年齡稍大的青少年用戶。(公司表示17至24歲的年輕人是增長(zhǎng)最快的用戶群體。)

公司重視這一點(diǎn)的理由顯而易見:作為一家公司,Roblox依賴用戶消費(fèi),而要依靠?jī)和鼙妼?shí)現(xiàn)這個(gè)目標(biāo)是一項(xiàng)復(fù)雜的挑戰(zhàn)。未成年用戶需要父母參與注冊(cè)Robux賬戶,但除此之外,成年人的監(jiān)督參差不齊,留下了發(fā)生可疑交易的可能性。4月,非營(yíng)利組織廣告中的真相(Truth In Advertising)向聯(lián)邦貿(mào)易委員會(huì)(Federal Trade Commission)投訴,指責(zé)Roblox“通過(guò)多種方式允許將廣告與有機(jī)內(nèi)容秘密關(guān)聯(lián)。”與此同時(shí),該平臺(tái)在最近的一次流行文化事件中似乎扮演了不幸的角色。金·卡戴珊6歲的兒子最近在Roblox上偶然發(fā)現(xiàn)的一條內(nèi)容,提到了卡戴珊和前男友的性愛(ài)錄像帶。(據(jù)報(bào)道,該公司刪除了提及這個(gè)錄像帶的“體驗(yàn)”,并封殺了其創(chuàng)作者。)騙人的機(jī)器人程序也是一個(gè)問(wèn)題。Roblox為一項(xiàng)用于發(fā)現(xiàn)假冒虛擬物品的技術(shù)提交了專利申請(qǐng)。

即使是合法銷售也會(huì)引發(fā)人們的擔(dān)憂,因?yàn)殇N售的對(duì)象是未成年消費(fèi)者,他們的大腦尚未發(fā)育完全。有些活動(dòng)有意吸引人們?cè)谠撈脚_(tái)上大量消費(fèi)。據(jù)媒體報(bào)道,Lil Nas X在Roblox上舉辦的一場(chǎng)活動(dòng)的數(shù)字商品銷售額接近1,000萬(wàn)美元。某些稀有物品的價(jià)格高達(dá)數(shù)千枚Robux。這些物品之所以稀有是因?yàn)槠湓谔囟ㄓ螒蛑械膶?shí)用性,或者因?yàn)槠渖矸輪?wèn)題,將其稀缺性與現(xiàn)實(shí)世界的價(jià)值掛鉤。

作家、游戲設(shè)計(jì)師和批評(píng)家以及華盛頓大學(xué)圣路易斯分校(Washington University in St. Louis)傳媒與計(jì)算機(jī)科學(xué)教授伊恩·博格斯特表示:“在Roblox上有很多欺騙消費(fèi)者的機(jī)會(huì),尤其是兒童。”比如迫使消費(fèi)者購(gòu)買“禮物”,或者以低于真實(shí)價(jià)值的價(jià)格賣掉他們的數(shù)字物品等。

但博格斯特發(fā)現(xiàn),從《口袋妖怪》(Pokémon)狂熱到《堡壘之夜》(Fortnite)引發(fā)的擔(dān)憂,這類暴力游戲在家長(zhǎng)當(dāng)中造成的恐慌,并沒(méi)有對(duì)Roblox產(chǎn)生影響。或許這與Roblox方方正正、毫無(wú)威脅甚至有些笨重的審美有關(guān)。博格斯特表示:“或許家長(zhǎng)認(rèn)為:‘它可能不是很重要。因?yàn)橹匾臇|西應(yīng)該看起來(lái)更精致。”

Roblox提到其內(nèi)容審查工作稱,公司在內(nèi)容審查方面付出了大量努力,這也是公司的主要支出項(xiàng)目之一。此外,筆者采訪過(guò)的Roblox高管和開發(fā)者都提到了平臺(tái)的“社區(qū)”環(huán)境,因?yàn)檫@是一個(gè)基本上由用戶創(chuàng)造的世界,維持一個(gè)誠(chéng)信、安全的環(huán)境符合用戶的既得利益。

Roblox最終也需要維持這樣一個(gè)環(huán)境:公司幾乎在所有層面,都將未來(lái)寄托于其培養(yǎng)的生態(tài)系統(tǒng)的創(chuàng)造力、敏銳度和道德原則。對(duì)傳統(tǒng)收益不屑一顧這種策略并不能持久,而且華爾街似乎正在失去耐心。但正如多納托所說(shuō),這家有18年歷史的公司相信,現(xiàn)在強(qiáng)勁的現(xiàn)金流量未來(lái)將演變成利潤(rùn)。“我們才剛剛起步。”(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

翻譯:劉進(jìn)龍

審校:汪皓

A couple of years ago, Marcus Holmstr?m and his Stockholm-based game studio, the Gang Sweden, were approached by an entertainment-industry client about building something for the Roblox platform—a metaverse-style collection of games and diversions executed with blocky graphics and wildly popular with kids.

It sounded like an opportunity for an easy win: Members of Holmstr?m’s team had loads of experience with so-called AAA games—some had worked on mainstream blockbusters like Return to Castle Wolfenstein and Warhammer: Vermintide—while much of what was happening on Roblox was built by the platform’s own community. “We thought we were going to do really, really well,” Holmstr?m recalls, “because the competition was really low.”

Wrong. “Crash and burn,” Holmstr?m admits. “Nobody liked our game.” The Gang Sweden learned the hard way that Roblox was something singular.

For starters, their game was heavily goal- and competition-oriented—you know, like a game. But lots of tween Roblox users were really on the platform to hang out with each other, almost like it was a social network; turns out there’s a lot of free-form loitering in the metaverse. At the same time, the Gang’s game was complex, leaving a lot up to users to figure out. The young Roblox audience, however, preferred a bit of hand-holding, with clear directives and activities. The studio realized the Roblox audience is engaged with the platform because it’s giving them what they want.

And that audience is not to be taken lightly: 54.1 million average daily active users spent a combined 11.8 billion hours on the platform in the first quarter of 2022. Many spend Robux—an in-platform currency you can acquire with actual dollars—on experiences as well as on digital wares to individualize their avatars or hangout spaces. And, perhaps most remarkably, over 10 million Roblox users have built experiences and games for others to enjoy—nearly 30 million of them, in fact. A good chunk of those users are earning money from their creations, to the tune of $538 million in 2021. While these are mostly young people who grew up on the platform, it’s hard to overstate the importance of these user/developers to the Roblox ecosystem. They basically are that ecosystem.

And yet, as remarkable a job as Roblox has done cultivating this community, the company remains well short of profitability. In 2021, it reported a loss of about $490 million on $1.92 billion revenue. And as a usage surge fueled partly by the pandemic showed signs of cooling down, Wall Street lost enthusiasm for the Roblox story; its share price has dropped by more than half since its November peak.

Even so, that hasn’t scared off the likes of the Gang, let alone the legions of self-starter creators building on the platform. In fact, the Roblox ecosystem has become increasingly robust: Some indie developers are morphing into professional studios, and experienced gamemakers are positioning themselves as Roblox specialists, sometimes with venture capital backing.

Marcus

The Gang Sweden is now focused exclusively on Roblox. With 67 employees, it has created more than 15 games, including the bona fide, million-player-a-day hit Strongman Simulator (which involves visiting a virtual gym-like environment and performing various feats for strength and energy points). Its games generate revenue through the sale of upgrades as well as items like virtual clothes and gear. The company also builds custom environments for clients like Vans and supercar-maker McLaren.

Plenty of other studios are pursuing similar models on the platform. Branded experiences from a Hello Kitty café to a Chipotle “burrito building” game to “music-themed islands” from Spotify to “Gucci Town” have become a routine feature of the ecosystem. (That’s a development that has attracted criticism from advertising watchdogs.)

The upshot is that the Gang Sweden—which Holmstr?m says is profitable, with rapidly growing revenue—is one of many examples of a third party that has figured out how to make money on Roblox.

The question is whether Roblox can figure out how to make money, too.

*

Roblox may seem like a recent phenomenon—it went public in March 2021—but the enterprise has been around since 2004. What’s much newer is its current operational model, which revolves entirely around encouraging third-party developers—from the creative teenage amateur in her bedroom all the way up to studios stocked with game veterans. Sign up for a Roblox account today and you’re presented with a blizzard of options for exploring its version of the metaverse. The number of these options that were created by Roblox itself is close to zero.

Or, you could argue, Roblox created all of it. Devising the right set of digital building tools, crafting the right incentives, and actively cultivating a sprawling developer community is itself a creative act. And it took years of experimentation and course correction.

In its earliest days, Roblox resembled a “l(fā)earning tool,” says Justin Sousa, senior director and global head of developer community at the company. A kind of physics simulator that kids could use to make objects and spaces with digital blocks, it attracted “nerdy kids” (Sousa means that as a compliment) in the 12-to-14 age range. For a time the company experimented with an advertising model, ultimately deciding that this didn’t mesh well with the community that was taking shape.

Instead, Roblox doubled down on that community, and on the idea of its metaverse as a place where people spend money. Essentially embracing the now-familiar “creator economy” model, the company began more actively encouraging developers to make monetizable experiences on the platform—and taking a cut of the proceeds. When a Roblox user buys digital accoutrements for their avatar, objects to fancy up their virtual spaces, and the like, the company keeps about 30% for “platform fees.”

In 2015 Roblox launched what it called an “accelerator” program to help select homegrown developers up their game, through a kind of boot camp, currently offering about 40 developers a year specialized training and direct access to its engineers and other Roblox insiders. At first, the company encouraged certain kinds of games and experiences, but soon it shifted to just supporting whatever the developers wanted to do. “We merely give you the hammer,” Sousa insists. “I don’t care if you build a house, shack, or a shoe, that’s up to you.” (Actually, Roblox later clarified, there are limits: The company has elaborate community guidelines and parental control settings intended to keep the platform safe and appropriate for its young audience.) More recently, Roblox has kicked off an even more open-ended Game Fund initiative, doling out $25 million in grants to developers.

Some graduates of the accelerator program have gone on to start their own studios. Nathan Clemens, founder of Simple Games, is one example. He’s 21, and his partners are his sisters, Naomi (18) and Rachel (15), and their parents. Working with a team of contract coders, they’ve produced about 15 games, including a popular role-playing game called City Life, with total revenue in the low seven figures. (Clemens won’t get specific, but notes that Simple Games has given more than $150,000 to charity.)

“I never really played Roblox,” Clemens confesses, and in fact he’s never been much of a gamer. But he discovered the platform—and, more to the point, its Roblox Studio building tools—when he was about 14. By then he’d already learned 3D modeling and computer-aided design (CAD) rendering, using programs like Google SketchUp. He realized he could make money applying those skills for people developing Roblox games. And then he realized he could work with programmers and make his own games. “From there,” he says, “we learned just how large the market was.”

His parents, Jeff and Shannon, kept an eye on this, and as Nathan’s enterprise grew they got directly involved, mostly on the business side. Naomi joined in at age 15, developing her own projects; her newest is called Layered Clothing, basically a virtual dress-up competition designed to take advantage of a new Roblox feature that improves the results of tricking out your avatar. Rachel, who has a digital art bent and is fluent in programs like Procreate, joined in at around 12.

Nathan describes his experience in the accelerator program as transformative. At 18, he spent three months in California, with Roblox’s financial support, focused entirely on the ins and outs of making the most of the platform, through programs and presentations on everything from interaction design to finances. “It’s chaos, and it’s amazing,” he says. “After that I was Roblox full-time.”

*

He’s not the only one. In fact the Roblox ecosystem, after years of slow and gradual growth, seems in the past couple of years to have achieved the virtuous flywheel effect that creator-economy companies covet: The more people are able to make a living—or even become a millionaire—by developing on the platform, the more users they bring in; and the more user engagement grows, the more attractive it is to develop for the platform. At this point, Roblox culture transcends actual participation on the platform—there are Roblox-oriented YouTubers and publications and Twitch broadcasters, and the company hosts annual developer events where creators mingle and forge new relationships (and deals).

Given all this, why is Roblox still reporting negative earnings? Roblox chief business officer Craig Donato argues that this is the wrong question. “Internally, we don’t talk about revenue and profitability,” he says. Instead, the company focuses on “bookings,” and cash flow. Roblox collects cash when a user buys Robux, its in-platform currency. (The cost varies depending on how many you buy and whether you choose a “subscription” option that bills you for fresh Robux every month, but, for instance, you can buy 800 Robux for about $10.)

Generally, users go on to spend those Robux on experiences or virtual objects, and that revenue is amortized over the lifetime of the things they buy; a virtual shirt, for instance, might be amortized over 25 months. The upshot, according to Donato, is that while this slows earnings, the company is cash-flow positive: “Our bank account is getting larger, not smaller.”

Skeptics point to Roblox’s softer numbers since pandemic lockdown life has ebbed: Total estimated bookings are down a couple of percentage points from a year ago, and the per-user booking average has slipped too. Analysts have cut their revenue estimates, and in some cases become more openly bearish. Goldman Sachs analyst Eric Sheridan, for instance, recently dropped his outlook on the stock from buy to neutral, citing the likelihood of continuing slowed user growth in the short term; and Bank of America analyst Omar Dessouky has lately slashed his RBLX price target.

For its part, Roblox appears to view both the COVID-era spike and its subsequent fade as anomalous moments on an overall growth path. And the company shows no signs of wavering from its strategy of doing everything it can to boost growth—investing in the platform, expanding servers, and, most crucially, greasing that creator/content flywheel. The essential idea is that eventually, there will be enough users spending enough money on the platform that income from “bookings” eclipses the costs of expansion and platform maintenance, resulting in traditional profits. (Even some of Roblox’s Wall Street critics tend to see the company’s long-term prospects as promising, particularly if you’re a believer in the potential of the metaverse.)

Two of its strategies to that end seem particularly notable. One is the introduction, in 2019, of “engagement based” payments to developers. For fledgling creators, it can take time to build up enough of an audience to realistically monetize a game or experience. These payouts can serve as an incentive, or stopgap measure. The developer doesn’t even have to pursue them; funds simply show up in their Robux account. “We want them to be able to earn money as they’re investing time,” Donato says. Roblox doled out $86.1 million in engagement payouts in 2021—about 16% of total payments to developers.

Second, Roblox has adopted a seemingly neutral relationship to brand incursions on the platform. This is striking because those incursions are definitely happening, and it seems likely their frequency and pervasiveness will increase—as well as their potential for monetization. But Roblox currently doesn’t seem to want to deal with brands directly; instead, it encourages them to work with developers—whether homegrown like the Clemens family, or outsider pros like the Gang.

The bottom line, Donato says, is that it’s easier to just let that dynamic play out within the ecosystem, and for brand experiences to rise or fall on their own merits, rather than try to play a more direct partnership role. In fact, Sousa, the developer lead, notes that Adopt Me (one of the most popular games on Roblox, involving caring for and swapping virtual pets) has included multiple brand “integrations” linked to Disney properties. That, he says, is what Roblox generally prefers: brand involvement, but without the company serving as the direct middleman. “We just try to create a level playing field,” Donato agrees.

*

There’s a third strategy that has had only light impact so far but could turn out to be a crucial part of Roblox’s future. Sousa points out that the average age of Roblox users is creeping slightly upward: 52% are now over 13. Seeing that number go up—or being “age agnostic,” as Sousa puts it—has become a company goal. Thus the encouragement of experiments like yoga spaces, or realistic travel-oriented experiences. Even digital events like concerts and DJ sets can attract a slightly older teen audience. (The company says 17- to 24-year-olds are its fastest-growing user group.)

One obvious reason for this emphasis: As a business, Roblox depends on users spending money, and accomplishing that goal with an audience of children is a complicated challenge. Younger users need parental involvement to set up Robux accounts, but adult supervision beyond that varies widely, leaving open the possibility of dubious transactions. In April, the nonprofit group Truth In Advertising filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission, charging that Roblox “allows advertising to be surreptitiously interlaced with organic content in a multitude of ways.” Around the same time, the platform made an unfortunate cameo in pop culture when Kim Kardashian’s 6-year-old son apparently encountered a mention within Roblox of a sex tape of her and a former boyfriend. (The company reportedly removed the “experience” where the tape was mentioned, and banned its creator.) Scammy bots are also a problem, and Roblox has filed a patent for a technology designed to ferret out counterfeit versions of virtual goods.

Even legitimate sales can raise concerns when you’re talking about preteen consumers whose brains are still literally developing. And there is, by design, a lot of spending on the platform. Digital merch sales from a Lil Nas X Roblox event reportedly approached $10 million. Certain rare items—coveted either because of their utility in a particular game, or simply for the same status reasons that link scarcity and value in the physical world—cost thousands of Robux.

“There’s a lot of opportunity to scam people in Roblox, especially kids,” notes Ian Bogost, an author, game designer, and critic, and media and computer science professor at Washington University in St. Louis. That could involve anything from pressuring them into buying “gifts” or giving away digital objects they’ve acquired, for less than their true value.

But as Bogost observes, Roblox has managed to remain remarkably unscathed by the kind of parental panics that have surrounded everything from violent games to the Pokémon craze to concerns over Fortnite. Perhaps it has something to do with Roblox’s blocky, nonthreatening, even clunky aesthetic, Bogost says: “Maybe parents think: ‘It can’t be that important. Something that was important would look better.’”

Roblox points to its content moderation efforts, which it describes as extensive, and as one of the company’s significant expenses. In addition, the Roblox executives and developers I spoke to repeatedly cited the platform’s “community” environment—precisely because it’s a world that’s been built largely by its users, users have a vested interest in keeping it honest and safe.

Ultimately, Roblox needs that to be true: On almost every level, it has bet its future on the creativity, acumen, and ethics of the ecosystem it has cultivated. Shrugging off traditional earnings isn’t a strategy that works for long, and Wall Street already seems to be losing some patience. But as Donato says, the 18-year-old company believes that today’s strong cash flow numbers will evolve into tomorrow’s profits. “We’re just getting going.”