8月30日,當(dāng)最后一架美國軍用飛機于午夜到來前的一分鐘從阿富汗的喀布爾機場起飛時,美國似乎關(guān)上了長達20年戰(zhàn)爭的大門。而此時距離2001年10月美軍在那里投下第一批炸彈,已經(jīng)過了整整7267天。“我們的外交將發(fā)揮帶頭作用。”為了紀(jì)念這一時刻,美國國務(wù)卿安東尼·布林肯在華盛頓發(fā)表講話說,“軍事任務(wù)已經(jīng)結(jié)束。”

這也許是“結(jié)束”,也許并沒有。戰(zhàn)爭過后,留下的是巨額的開支,其中大部分來自借款資助。阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭帶來的財政影響可能會持續(xù)長達幾十年。

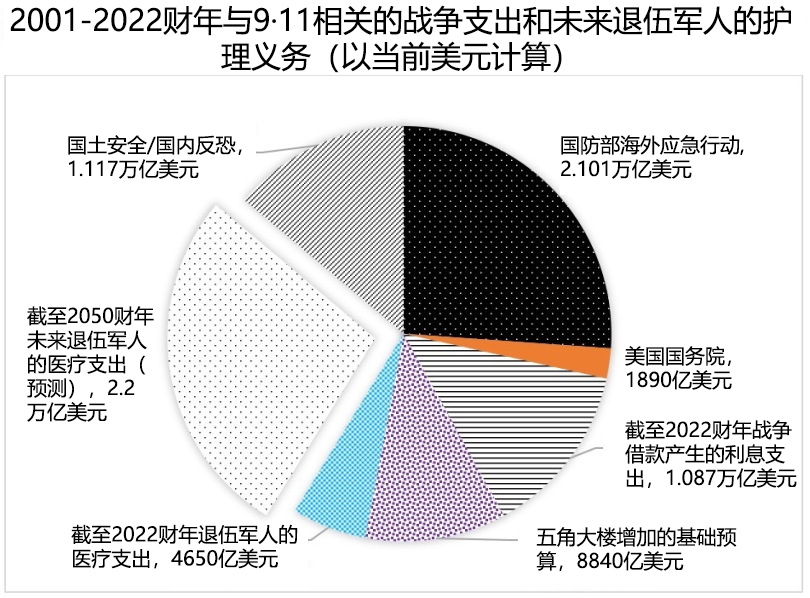

在9月1日公布的兩份報告中,經(jīng)濟學(xué)家和社會科學(xué)家分析了阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭,以及規(guī)模小得多的敘利亞和也門戰(zhàn)爭的成本。他們得出的結(jié)論是:最終成本超過8萬億美元,遠高于此前的估計。他們計算,美國僅在阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭上就花費了2萬億美元——這一數(shù)字是美國總統(tǒng)喬·拜登于8月16日所說的兩倍。當(dāng)時,他為從阿富汗混亂的撤軍辯護:“我們總共花了超過1萬億美元。”

從某一方面來看,拜登是正確的:這1萬億美元包括了五角大樓自2001年以來為阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭提供的所有軍事?lián)芸睿坏牵@個數(shù)字不包括美國為戰(zhàn)爭借款支付的利息,也不包括美國迄今為止向在阿富汗和伊拉克陣亡的7000多名美國士兵(其中2461名在阿富汗)的親眷支付的約7.04億美元的死亡撫恤金。這個數(shù)字是布朗大學(xué)(Brown University)的沃森研究所(Watson Institute)與波士頓大學(xué)(Boston University)的弗雷德里克·帕迪中心(Frederick S. Pardee Center)合作的“戰(zhàn)爭成本”(Costs of War)項目發(fā)布的《“9·11”事件之后美國戰(zhàn)爭預(yù)算成本》(The U.S. Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars)報告中披露的幾個數(shù)字之一。

戰(zhàn)爭支出中最昂貴的一項,遠遠超過了美國混亂的撤軍所需要的時間——那就是為受傷退伍軍人提供的醫(yī)療福利。報告估計,到2050年,這一福利支出總計將達到約2.3萬億美元。研究人員說,這項支出是過去20年戰(zhàn)爭造成的最不為人所知的經(jīng)濟負擔(dān)之一。

“針對退伍軍人的撫恤已經(jīng)付出了多少錢,將來會付出多少錢——這是一直讓我感到驚訝的事情。”報告作者、波士頓大學(xué)政治學(xué)教授、“戰(zhàn)爭成本”項目的聯(lián)合主任內(nèi)塔·C·克勞福德稱。“這些老兵比以前的戰(zhàn)爭中病得更重,受傷的老兵也更多。”她說。這些費用包括對創(chuàng)傷后應(yīng)激障礙和創(chuàng)傷性腦損傷的長期治療,而這些疾病在20世紀(jì)70年代從越南戰(zhàn)爭撤回的退伍軍人中從未得到診斷。大約5萬名美國士兵在阿富汗和伊拉克受傷。

盡管金額眼花繚亂,但很少有美國人感受到了這幾十年戰(zhàn)爭所帶來的財政負擔(dān),尤其是在聯(lián)邦稅收下降、軍事成本卻在不斷膨脹的情況下。阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭的幾乎所有成本都來自借款,而其中大部分尚未償還。

“很難想象我們談?wù)摰奈磥頃绞裁闯潭取!笨藙诟5聦Α敦敻弧冯s志表示,“從百萬到十億再到萬億,看起來都是連續(xù)的數(shù)字后綴,但是每一個級別的增量,都意味著數(shù)字增加了1000倍。當(dāng)你關(guān)注到我們將升級美國的所有基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施時,你會發(fā)現(xiàn)其所需的一切支出都可以用1萬億美元來完成。”她說。

事實上,9月1日公布的另一份報告計算得出,如果美國沒有發(fā)動阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭,國家可能會在哪些方面花費數(shù)萬億美元。總部位于華盛頓的美國政策研究所(Institute of Policy Studies)表示,用于軍事戰(zhàn)爭的資金本來能夠解決美國的許多問題,例如,用1.7萬億美元可以還清所有的學(xué)生債務(wù),用4.5萬億美元讓整個電網(wǎng)的碳排放清零,還能夠向所有低收入國家提供新冠疫苗——最后這一項的費用甚至僅為250億美元,僅僅略高于五角大樓2020年為阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭提供的最后一年預(yù)算——200億美元。

“這確實是一個權(quán)衡問題。”美國政策研究所的報告《不安全狀態(tài):“9·11”事件以來軍事化的代價》(State of Insecurity: the Cost of Militarization Since 9/11)的作者林賽·科什格里安認(rèn)為。正如她對《財富》雜志所言:“我們在一件事情上花的錢越多,在其他事情上花的錢就越少。”

一些分析人士表示,這些權(quán)衡也扭曲了軍事戰(zhàn)略。他們認(rèn)為,五角大樓對阿富汗和伊拉克的高度關(guān)注,犧牲了其處理過去20年里逐漸出現(xiàn)的其他沖突的可能性。

美國政策研究所的國家優(yōu)先項目(National Priorities Project)的負責(zé)人科什格里安認(rèn)為,如果把軍費預(yù)算重新分配到醫(yī)療和教育領(lǐng)域,許多美國人會支持削減軍事預(yù)算。但去年,兩項分別削減10%預(yù)算的提案均未能夠在美國國會通過。現(xiàn)在,關(guān)于是批準(zhǔn)拜登提出的明年7150億美元軍費開支的請求,還是在阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭已經(jīng)結(jié)束的情況下削減預(yù)算這一問題,政界人士存在嚴(yán)重分歧。

最終,美國人可能仍然不會感受到軍事成本的存在,就像他們在過去20年沒有感受到經(jīng)濟拮據(jù)的情況一樣。隨著最后一名美軍撤出阿富汗,“數(shù)千億美元”的概念似乎越來越抽象。

不過,科什格里安相信大多數(shù)人會支持削減軍事開支,以支持醫(yī)療保健、教育和基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施建設(shè)的發(fā)展。“美國民眾想要的,和我們在華盛頓的代表給我們的之間存在很大的分歧。”她說,“當(dāng)美國民眾去投票時,國家安全和外交政策不是最重要的考慮因素。”(財富中文網(wǎng))

編譯:楊二一

8月30日,當(dāng)最后一架美國軍用飛機于午夜到來前的一分鐘從阿富汗的喀布爾機場起飛時,美國似乎關(guān)上了長達20年戰(zhàn)爭的大門。而此時距離2001年10月美軍在那里投下第一批炸彈,已經(jīng)過了整整7267天。“我們的外交將發(fā)揮帶頭作用。”為了紀(jì)念這一時刻,美國國務(wù)卿安東尼·布林肯在華盛頓發(fā)表講話說,“軍事任務(wù)已經(jīng)結(jié)束。”

這也許是“結(jié)束”,也許并沒有。戰(zhàn)爭過后,留下的是巨額的開支,其中大部分來自借款資助。阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭帶來的財政影響可能會持續(xù)長達幾十年。

在9月1日公布的兩份報告中,經(jīng)濟學(xué)家和社會科學(xué)家分析了阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭,以及規(guī)模小得多的敘利亞和也門戰(zhàn)爭的成本。他們得出的結(jié)論是:最終成本超過8萬億美元,遠高于此前的估計。他們計算,美國僅在阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭上就花費了2萬億美元——這一數(shù)字是美國總統(tǒng)喬·拜登于8月16日所說的兩倍。當(dāng)時,他為從阿富汗混亂的撤軍辯護:“我們總共花了超過1萬億美元。”

從某一方面來看,拜登是正確的:這1萬億美元包括了五角大樓自2001年以來為阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭提供的所有軍事?lián)芸睿坏牵@個數(shù)字不包括美國為戰(zhàn)爭借款支付的利息,也不包括美國迄今為止向在阿富汗和伊拉克陣亡的7000多名美國士兵(其中2461名在阿富汗)的親眷支付的約7.04億美元的死亡撫恤金。這個數(shù)字是布朗大學(xué)(Brown University)的沃森研究所(Watson Institute)與波士頓大學(xué)(Boston University)的弗雷德里克·帕迪中心(Frederick S. Pardee Center)合作的“戰(zhàn)爭成本”(Costs of War)項目發(fā)布的《“9·11”事件之后美國戰(zhàn)爭預(yù)算成本》(The U.S. Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars)報告中披露的幾個數(shù)字之一。

戰(zhàn)爭支出中最昂貴的一項,遠遠超過了美國混亂的撤軍所需要的時間——那就是為受傷退伍軍人提供的醫(yī)療福利。報告估計,到2050年,這一福利支出總計將達到約2.3萬億美元。研究人員說,這項支出是過去20年戰(zhàn)爭造成的最不為人所知的經(jīng)濟負擔(dān)之一。

“針對退伍軍人的撫恤已經(jīng)付出了多少錢,將來會付出多少錢——這是一直讓我感到驚訝的事情。”報告作者、波士頓大學(xué)政治學(xué)教授、“戰(zhàn)爭成本”項目的聯(lián)合主任內(nèi)塔·C·克勞福德稱。“這些老兵比以前的戰(zhàn)爭中病得更重,受傷的老兵也更多。”她說。這些費用包括對創(chuàng)傷后應(yīng)激障礙和創(chuàng)傷性腦損傷的長期治療,而這些疾病在20世紀(jì)70年代從越南戰(zhàn)爭撤回的退伍軍人中從未得到診斷。大約5萬名美國士兵在阿富汗和伊拉克受傷。

盡管金額眼花繚亂,但很少有美國人感受到了這幾十年戰(zhàn)爭所帶來的財政負擔(dān),尤其是在聯(lián)邦稅收下降、軍事成本卻在不斷膨脹的情況下。阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭的幾乎所有成本都來自借款,而其中大部分尚未償還。

“很難想象我們談?wù)摰奈磥頃绞裁闯潭取!笨藙诟5聦Α敦敻弧冯s志表示,“從百萬到十億再到萬億,看起來都是連續(xù)的數(shù)字后綴,但是每一個級別的增量,都意味著數(shù)字增加了1000倍。當(dāng)你關(guān)注到我們將升級美國的所有基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施時,你會發(fā)現(xiàn)其所需的一切支出都可以用1萬億美元來完成。”她說。

事實上,9月1日公布的另一份報告計算得出,如果美國沒有發(fā)動阿富汗和伊拉克戰(zhàn)爭,國家可能會在哪些方面花費數(shù)萬億美元。總部位于華盛頓的美國政策研究所(Institute of Policy Studies)表示,用于軍事戰(zhàn)爭的資金本來能夠解決美國的許多問題,例如,用1.7萬億美元可以還清所有的學(xué)生債務(wù),用4.5萬億美元讓整個電網(wǎng)的碳排放清零,還能夠向所有低收入國家提供新冠疫苗——最后這一項的費用甚至僅為250億美元,僅僅略高于五角大樓2020年為阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭提供的最后一年預(yù)算——200億美元。

“這確實是一個權(quán)衡問題。”美國政策研究所的報告《不安全狀態(tài):“9·11”事件以來軍事化的代價》(State of Insecurity: the Cost of Militarization Since 9/11)的作者林賽·科什格里安認(rèn)為。正如她對《財富》雜志所言:“我們在一件事情上花的錢越多,在其他事情上花的錢就越少。”

一些分析人士表示,這些權(quán)衡也扭曲了軍事戰(zhàn)略。他們認(rèn)為,五角大樓對阿富汗和伊拉克的高度關(guān)注,犧牲了其處理過去20年里逐漸出現(xiàn)的其他沖突的可能性。

美國政策研究所的國家優(yōu)先項目(National Priorities Project)的負責(zé)人科什格里安認(rèn)為,如果把軍費預(yù)算重新分配到醫(yī)療和教育領(lǐng)域,許多美國人會支持削減軍事預(yù)算。但去年,兩項分別削減10%預(yù)算的提案均未能夠在美國國會通過。現(xiàn)在,關(guān)于是批準(zhǔn)拜登提出的明年7150億美元軍費開支的請求,還是在阿富汗戰(zhàn)爭已經(jīng)結(jié)束的情況下削減預(yù)算這一問題,政界人士存在嚴(yán)重分歧。

最終,美國人可能仍然不會感受到軍事成本的存在,就像他們在過去20年沒有感受到經(jīng)濟拮據(jù)的情況一樣。隨著最后一名美軍撤出阿富汗,“數(shù)千億美元”的概念似乎越來越抽象。

不過,科什格里安相信大多數(shù)人會支持削減軍事開支,以支持醫(yī)療保健、教育和基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施建設(shè)的發(fā)展。“美國民眾想要的,和我們在華盛頓的代表給我們的之間存在很大的分歧。”她說,“當(dāng)美國民眾去投票時,國家安全和外交政策不是最重要的考慮因素。”(財富中文網(wǎng))

編譯:楊二一

When the last U.S. military aircraft lifted off from Kabul Airport a minute before midnight in Afghanistan on August 30—7,267 days after dropping the first bombs there in October 2001—America seemingly shut the door on the 20-year war, and moved on. “We will lead with our diplomacy,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a speech in Washington, to mark the moment. “The military mission is over.”

“Over,” perhaps—though not wrapped up. Left behind is the war’s mammoth expense, the bulk of it financed with borrowed money and whose financial impact could be felt for decades.

In two reports out on September 1, economists and social scientists unpacking the costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, and far smaller engagements in Syria and Yemen, put the final tab at more than $8 trillion, well above previous estimates. About $2 trillion, they calculate, was spent on the Afghanistan war alone—double what President Joe Biden stated on Aug. 16, when he defended the tumultuous withdrawal from Afghanistan, in part by saying, “We spent over a trillion dollars.”

Biden was correct in one respect: The trillion-dollar sum comprises all military appropriations by the Pentagon for the Afghanistan war since 2001. But the figure did not include the interest payments on money the U.S. borrowed to fight the war. Nor did it include death benefits of about $704 million paid so far to the survivors of more than 7,000 U.S. soldiers killed in Afghanistan and Iraq, about 2,461 of them in Afghanistan. That figure is among several revealed in one of the new reports, The U.S. Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars, published by the Costs of War project at Brown University’s Watson Institute and Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee Center.

But the biggest-ticket item of all will far outlast the chaotic U.S. withdrawal: The medical benefits for wounded veterans, which the report estimates could reach about $2.3 trillion by 2050. That figure, say the researchers, is among the least-known financial burdens from the past two decades of war.

“What has consistently surprised me is how much veterans’ care has cost and will cost,” said the author of the report Neta C. Crawford, political science professor at Boston University and codirector of the Costs of War project. “These vets are sicker, and more injured, than in previous wars,” she said. The costs include long-term treatment for post-traumatic stress disorders and traumatic brain injuries—conditions that went undiagnosed among the vets who returned home from the Vietnam War in the 1970s. About 50,000 U.S. soldiers were wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Despite the dizzying sums, few Americans have felt the financial burden from decades of war, especially since their federal taxes have gone down even while military costs have ballooned. Almost the entire cost of the Afghan and Iraq wars has come from borrowed money, much of which has yet to be repaid.

“It is difficult to image the scale of what we are talking about into the future,” Crawford told Fortune. “Million, billion, trillion—it all rhymes, but you’re looking at 1,000 times more with each increment,” she says. “When you look at how we’ll upgrade all the infrastructure in the U.S., it could all be done with a trillion dollars.”

Indeed, a second report, also out on September 1, calculates what the U.S. might have spent those trillions on, had it not launched wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Washington-based Institute of Policy Studies, or IPS, says the money spent on military combat could have solved multiple problems in the U.S., like erasing all student debt for $1.7 trillion, decarbonizing the entire electricity grid for $4.5 trillion, or providing COVID-19 vaccines to all low-income countries for just $25 billion—only slightly higher than the $20 billion the Pentagon budgeted in 2020 for the final year of the Afghan War.

“It really does come down to tradeoffs,” said Lindsay Koshgarian, who wrote the institute’s report, State of Insecurity: The Cost of Militarization Since 9/11. As she told Fortune, “The more we are spending on one thing, the less we are spending on other things.”

Those tradeoffs have also skewed military strategy, according to some analysts, who argue that the Pentagon’s intense focus on Afghanistan and Iraq has come at the expense of dealing with other conflicts that steadily emerged during the past 20 years.

Koshgarian, who heads the National Priorities Project at IPS, believes many Americans would support cuts in the military budget if the money was reallocated to health care and education. But last year two separate proposals for a 10% cut failed to pass in Congress. Now politicians are bitterly divided over whether to approve Biden’s request for $715 billion in military spending for the coming year or whether to cut the budget, now that the Afghan War has ended.

In the end Americans might not feel the military cost—just as they did not feel the pinch during the past 20 years. With the last U.S. soldier out of Afghanistan, the hundreds of billions could seem increasingly abstract.

Still, Koshgarian believes most would support cutting military spending in order to boost health care, education, and infrastructure. “There is a big divide between what Americans want and what our representatives in Washington are giving us,” she said. “National security and foreign policy are not top of the list when Americans go vote.”