這家老牌零售店有機會成為亞馬遜的,它做錯了什么?

|

50年前的西爾斯(Sears),猶如一臺轟鳴不息的經(jīng)濟發(fā)動機。就像今天的亞馬遜(Amazon)和沃爾瑪(Walmart)一樣,它是零售業(yè)的絕對霸主。1969年,西爾斯的銷售額占到整個美國經(jīng)濟的1%。在任何一個季度,三分之二的美國人在那里購物。即使在30年前,它還是遙遙領(lǐng)先的美國頭號零售商。 當然,那些日子已經(jīng)一去不復返了。西爾斯控股于去年10月申請破產(chǎn)保護,自世紀之交以來,該公司已經(jīng)關(guān)閉了數(shù)千家門店。《財富》雜志6月刊登了一篇名為《西爾斯的70年自毀之路》的文章,詳述了這家零售業(yè)巨頭的衰落歷程。本文將逐一闡述西爾斯曾經(jīng)手握勝券的四個領(lǐng)域,并展示該公司是如何痛失好局的。 |

Fifty years ago, Sears was an economic dynamo, as dominant in retail as Amazon and Walmart are today. In 1969, Sears sales alone accounted for 1% of the entire U.S. economy, and two-thirds of Americans shopped there in any given quarter. Even 30 years ago, it was America’s largest retailer by a significant margin. Those days are gone, of course. Sears Holdings filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last October, and the company has closed thousands of stores since the turn of the century. Fortune captures the sweep of that decline this month in the feature “Sears’ Seven Decades of Self-Destruction.” Here, we examine four arenas where Sears used to hold winning hands, and show how the company misplayed them all. |

****

?

|

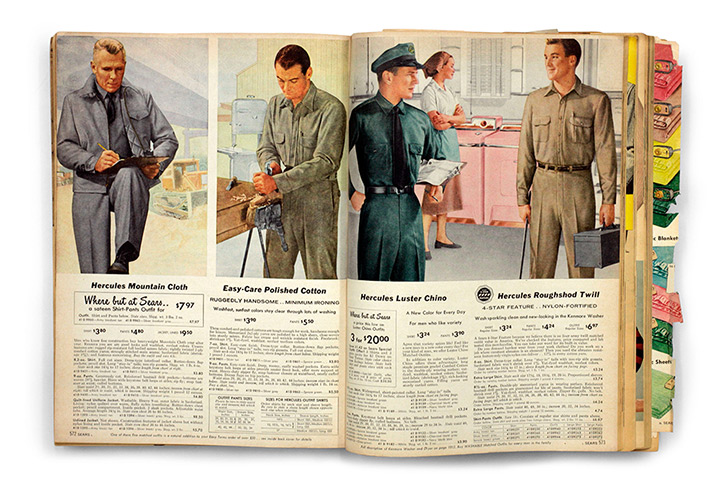

I. 網(wǎng)絡是如何丟失的 西爾斯本可以成為電子商務領(lǐng)域里強有力的競爭者。那么,它緣何被拋在后面? 龐大的客戶群;龐大的分銷網(wǎng)絡;對供應商的巨大影響力。這就是如今的亞馬遜,以及30年前的西爾斯所擁有的優(yōu)勢。有鑒于此,對于西爾斯來說,電子商務領(lǐng)域的霸主寶座似乎近在咫尺,唾手可得。 在1925年開設第一家門店之前的幾十年,西爾斯一直只做目錄郵購零售。在20世紀80年代的鼎盛時期,目錄郵購部門的年營業(yè)額高達40億美元,并且坐擁海量客戶信息。但到那時,郵寄一本1500頁商品目錄(即所謂的“大書”)的成本,再加上該目錄對低利潤產(chǎn)品的重視,讓這項業(yè)務變得無利可圖——每天虧損100萬美元。 1993年,西爾斯終止了這項業(yè)務,并拆除了分銷基礎(chǔ)設施,同時未能及時更新客戶名單。當西爾斯最終在1997年推出一個電子商務網(wǎng)站時,它不得不從頭開始重建許多基本元素,這是一項耗時又昂貴的工作。 盡管起步緩慢,西爾斯卻在某種程度上成為數(shù)字零售業(yè)的先驅(qū)。Sears.com為電子商務訂單提供店內(nèi)取貨服務,這種做法比梅西百貨(Macy’s)和塔吉特百貨(Target)早了好幾年。該網(wǎng)站不僅擁有強大的搜索功能,甚至還提供“虛擬模特”幫助顧客在線試穿衣服。 但遺憾的是,Sears.com仍然是西爾斯的一部分。到本世紀頭十年末,西爾斯的商品配置已經(jīng)變得相當平庸,以至于再多的網(wǎng)絡魔法也無法吸引新客戶。大批門店的關(guān)閉,也讓西爾斯無法實施許多零售商推崇的“實體店加網(wǎng)店”策略。市場研究公司eMarketer的數(shù)據(jù)顯示,2013年至2017年,隨著西爾斯的門店數(shù)量從828家縮減至570家,電子商務銷售額下降了50%,降至13億美元。 |

I. HOW THE WEB WAS LOST Sears could have been an e-commerce contender; here’s why it fell behind. A massive customer base. A vast distribution network. Enormous clout with vendors. That describes Amazon today—and Sears 30 years ago. Thanks to those advantages, e-commerce dominance was arguably Sears’ to lose. Sears was a catalog-only retailer for decades before it opened its first store in 1925. At its peak in the 1980s, the catalog division was a $4-billion-a-year business, perched atop a huge trove of customer information. But by then, the cost of mailing a 1,500-page catalog, known as the Big Book, along with the catalog’s emphasis on low-margin products, had made the business unprofitable. It was losing as much as $1 million a day. In 1993, Sears pulled the plug—and dismantled the distribution infrastructure while failing to keep updated customer lists. When Sears finally launched an e-commerce site in 1997, it had to rebuild many fundamental elements from scratch, a time-consuming and expensive undertaking. Despite the slow start, Sears became something of a digital-retail pioneer. Sears.com offered in-store pickup for e-commerce orders years before Macy’s or Target did. The site boasted great search functions and even offered “virtual models” to help customers try on clothes online. But Sears.com, alas, was still part of Sears. By the late 2000s, Sears’ merchandise assortment was so lackluster that no amount of online wizardry could lure new customers. And the closing of scores of stores deprived Sears of the visibility that sustains retailers’ “bricks and clicks” strategies. Between 2013 and 2017, as Sears’ fleet shrank from 828 to 570, e-commerce sales fell 50%, to $1.3 billion, according to eMarketer. |

****

?

|

II.門店:不斷下沉的西爾斯艦隊 這家零售商旗下的購物中心商場日益衰敗,從而難以維系其傳統(tǒng)的實體店優(yōu)勢。 在2005年策劃凱馬特(Kmart)與西爾斯合并之后,西爾斯控股的首席執(zhí)行官埃迪·蘭伯特明確表示,他將優(yōu)先考慮電子商務,而不是百貨商場。他徹底地貫徹了這一理念——以至于這兩項業(yè)務都蒙受了損失。哥倫比亞大學商學院零售研究主管、西爾斯加拿大公司前首席執(zhí)行官馬克·科恩表示:“如果你是一家價值500億美元的實體零售商,你就不能忽視自己的實體投資組合。” 從2005年到2012年,西爾斯在改善門店方面的花費只有區(qū)區(qū)33億美元左右。(西爾斯在此期間回購了60億美元的股票。)據(jù)分析師估計,以每平方英尺店面計算,沃爾瑪和塔吉特百貨等直接競爭對手的支出比西爾斯高出五倍。 西爾斯甚至切斷了基本的店面維護資金,由此形成了一個惡性循環(huán):商店變得越來越破舊,從而降低了它們創(chuàng)造收入的可能性,而這些收入本可以用來裝飾店面。但關(guān)閉衰敗的商店并沒有給Sears.com帶來流量;關(guān)閉也沒有幫到保留下來的店面。事實上,西爾斯控股從來沒有出現(xiàn)過一年的同店銷售額增長——這一指標剔除了新關(guān)閉門店的影響。 蘭伯特和他的前任們嘗試效仿更敏捷的競爭對手。2003年,該公司推出了Sears Grand的前身:一種規(guī)模更小,提供食物和藥品,并且“遠離商場”的店面。2000年至2005年擔任西爾斯首席執(zhí)行官的艾倫·萊西表示,一家典型的Sears Grand店面每年可以創(chuàng)造4500萬至6500萬美元的收入,是一些位于大型商場,規(guī)模兩倍于前者的店面所創(chuàng)造收入的兩倍多。但西爾斯最終只開了12家Sears Grand分店——數(shù)量太少,不足以抵消其他店面虧損和衰敗的影響。 |

II. STORES: SEARS’ SINKING FLEET The retailer’s portfolio of aging mall stores put the “ick” in “brick-and-mortar.” After engineering the 2005 merger of Kmart and Sears, Sears Holdings CEO Eddie Lampert made it clear that he would prioritize e-commerce over department stores. He followed through—so much so that both sides of the business suffered. “When you’re a $50 billion brick-and-mortar retailer, you can’t just ignore your brick-and-mortar portfolio,” says Mark Cohen, director of retail studies at Columbia Business School and a former CEO of Sears Canada. Between 2005 and 2012, Sears spent only about $3.3 billion on capital improvements to stores. (Sears bought back $6 billion in shares over that time frame.) Its immediate rivals, including Walmart and Target, outspent Sears five to one on a per-square-foot basis, according to analyst estimates. Cutting off funds for even basic upkeep created a vicious cycle in which stores grew shabbier and shabbier, making them less likely to generate revenue that could be used to spruce them up. But closing decaying stores didn’t drive traffic to Sears.com; nor did closures help the stores that remained. Indeed, Sears Holdings never enjoyed a single year of comparable sales growth, a metric that strips out the impact of newly closed stores. Lampert and his predecessors experimented with stores modeled after nimbler competitors. In 2003 the company launched the Sears Grand prototype—smaller, “off mall” locations with food and pharmacy offerings. Alan Lacy, the CEO of Sears from 2000 to 2005, says the typical Sears Grand pulled in between $45 million and $65 million a year—more than twice as much as some mall-based stores of double that size. But Sears ultimately opened only 12 Grands—too few to blunt the impact of red ink and peeling paint elsewhere. |

****

?

|

III. 家用電器:浪費主場優(yōu)勢 為什么房主們不愿意繼續(xù)在西爾斯購置廚房設備,積攢信用積分? 幾十年來,西爾斯一直是房主購買洗衣機和烤箱等高價家電的首選之地。2001年,該公司占據(jù)了美國家電市場41%的份額;直到2013年,西爾斯家電業(yè)務的銷售額仍然高達120億美元,占據(jù)29%的市場份額。 今天的家電收入只是其輝煌時期的一小部分。曾經(jīng)被西爾斯視為“皇冠上的寶石”的家電品牌Kenmore,已經(jīng)分拆成一家獨立的控股公司。頗具諷刺意味的是,你可以在亞馬遜上買到這家公司的產(chǎn)品。 到底是哪里出了錯?西爾斯在家電領(lǐng)域的主導地位,在很大程度上建立在它的信用卡業(yè)務之上。就在20世紀70年代,大批消費者還利用西爾斯商店卡購買家電,以積攢他們的信用積分。但隨著Visa和萬事達卡(Mastercard)持續(xù)增長,西爾斯對該渠道的掌控不再牢固。 更重要的是,大賣場競爭對手家得寶(Home Depot)和勞氏(Lowe’s)開始在更方便購物者的沿公路商業(yè)區(qū)擴張。與傳統(tǒng)的購物中心相比,沿公路商業(yè)區(qū)對裝車車位的限制更少,這使得新參與者可以提供像木材這樣的大型商品,也讓顧客更容易把它們運走。被困在購物中心的西爾斯永遠也無法認真應對這些零售商的入侵。前首席執(zhí)行官萊西指出,在他執(zhí)掌期間,西爾斯曾經(jīng)非常認真考慮收購勞氏公司。“這個機會被白白浪費了。”他哀嘆道。 直到2015年,西爾斯技術(shù)人員每年還在走訪800萬戶家庭進行家電配送和維修,并收集寶貴的客戶信息。這為西爾斯在智能家居和智能家電市場上搶占了先機。但不斷惡化的財務困境使得西爾斯無法在“家庭服務”領(lǐng)域堅持到底。百思買(Best Buy)和亞馬遜目前在這一領(lǐng)域占據(jù)主導地位。 |

III. APPLIANCES: SQUANDERING A HOME-FIELD ADVANTAGE Why homeowners stopped building their kitchens and their credit histories at Sears. For decades, Sears was homeowners’ go-to place for big-ticket appliances like washing machines and ovens. In 2001 it commanded 41% of the U.S. appliance market; as recently as 2013, that $12 billion business gave Sears a 29% market share. Appliance revenue today is a fraction of what it was in its glory days. And Kenmore, Sears’ former crown-jewel brand, has been spun off into a separate holding company whose products, ironically enough, you can buy on Amazon. What went wrong? Sears built its dominance in appliances in part on its credit card business. As recently as the 1970s, legions of consumers built their credit ratings by buying appliances with Sears store cards. But the growth of Visa and Mastercard loosened Sears’ grip on that channel. More crucially, big-box competitors Home Depot and Lowe’s started spreading in strip malls more convenient for shoppers. Strip centers had fewer restrictions on loading docks than traditional malls did, enabling the new players to offer more large goods like lumber and making it easier for customers to cart them away. Stuck in mall stores, Sears could never seriously counteract their incursions. Lacy, the former CEO, notes that Sears looked very hard at buying Lowe’s during his tenure. “That is the one that got away,” he laments. As recently as 2015, Sears technicians were visiting 8 million homes a year for appliance deliveries and repairs, gathering valuable customer info. This offered Sears a head start in the smart-home and smart-appliance markets. But worsening financial woes kept Sears from following through in “home services,” and Best Buy and Amazon now dominate that arena. |

****

?

|

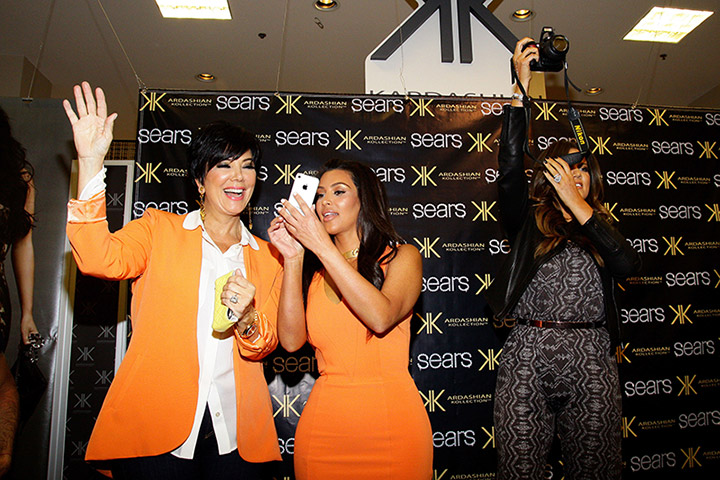

IV. 服裝和家居用品:西爾斯很一般的一面 當消費者更喜歡舊貨店,而不是你的購物中心商店時,你就有麻煩了。 西爾斯龐大的電器和工具業(yè)務,使其有別于以服裝聞名的競爭對手彭尼百貨(J.C. Penney)和梅西百貨。問題是:人們每隔幾年才會買一次冰箱或電鉆,而他們每年會置辦三到四次衣服。 在20世紀90年代,時任西爾斯首席執(zhí)行官的亞瑟·馬丁內(nèi)斯致力于推動西爾斯銷售高品質(zhì)服裝和家居用品,還特意發(fā)布了一個以“西爾斯更柔軟的一面”為主題,構(gòu)思巧妙的廣告宣傳活動,試圖以此來解決這一難題。但在上述商品類別中,這家零售商從未贏得消費者的心。“西爾斯很難與那些不想跟它產(chǎn)生聯(lián)系的品牌搞好關(guān)系。”前西爾斯在線服裝業(yè)務主管,目前供職于研究公司Gartner L2的查德·布萊特這樣說道。彭尼百貨和梅西百貨向那些在它們店內(nèi)銷售產(chǎn)品的知名供應商施壓,敦促后者不要在另一家連鎖店過度曝光。西爾斯并不以時裝聞名這一事實,也嚇跑了許多品牌。 即使西爾斯確實吸引了令人向往的品牌,其日益蹩腳的門店也損害了這種勢頭。2010年與快時尚零售商Forever 21的合作并沒有走多遠;2011年,就連如日中天的“卡戴珊旋風”,也未能阻止她們在西爾斯推廣的服飾品牌Kardashian Kollection徹底失敗。情況變得越來越糟糕。在2016年的一項調(diào)查中,女性消費者表示,她們寧愿去舊貨商店Goodwill買衣服,也不愿意去西爾斯。 糟糕的時機毀掉了一個“潛在”的合作關(guān)系。前首席執(zhí)行官萊西表示,2004年,他曾經(jīng)與瑪莎·斯圖爾特商談,試圖邀請她為西爾斯設計家居用品——斯圖爾特在凱馬特銷售的一個產(chǎn)品系列非常成功。由于斯圖爾特被判犯有與一樁內(nèi)幕交易案有關(guān)的罪名,相關(guān)談判最終擱淺。“我們差點就達成交易了,然后瑪莎進了監(jiān)獄。”萊西說。“這真的是造化弄人。”(財富中文網(wǎng)) 本文另一版本登載于《財富》雜志2019年6月刊,標題為《西爾斯的70年自毀之路》。 譯者:任文科 |

IV. APPAREL AND HOME GOODS: THE SO-SO SIDE OF SEARS When shoppers prefer thrift stores to your mall stores, you’ve got a problem. Sears’ huge appliance and tools businesses distinguished it from rivals like J.C. Penney and Macy’s, which were best known for apparel. The problem: People buy a fridge or power drill only once every few years, while they stock up on clothing three or four times a year. In the 1990s, then-CEO Arthur Martinez tackled the dilemma by committing Sears to selling higher-quality apparel and home goods, supported by the clever “Softer Side of Sears” ad campaign. But the retailer never caught on with consumers in those categories. “Sears struggled with brands not wanting to be associated with it,” says Chad Bright, a former Sears online apparel executive and a sector leader for big-box stores at Gartner L2. Penney’s and Macy’s pressured better-known vendors that sold in their stores, urging them not to overexpose themselves by selling through another chain. The fact that Sears simply wasn’t known for fashion scared others away. Even when Sears did lure desirable brands, its increasingly dumpy stores hurt momentum. A 2010 partnership with fast-fashion retailer Forever 21 didn’t go far; in 2011, even peak Kardashian mania couldn’t keep the Kardashian Kollection from flopping. Things got so bad that in a 2016 survey, female shoppers said they preferred thrift store Goodwill over Sears for clothing. Bad timing undid one “what if” partnership. Former CEO Lacy says that in 2004, he was in talks with Martha Stewart, who had a successful product line at Kmart, to create home goods for Sears. The talks were scotched by Stewart’s conviction on charges related to an insider-trading case. “We were darn close to getting that done—then Martha goes to jail,” Lacy says. “That was a bit of a snag.” A version of this article appears in the June 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “Seven Decades of Self-Destruction.” |