這項(xiàng)科技會引領(lǐng)硅谷的下一次革命嗎?

|

短短四年前,亞馬遜還只是一家很成功的在線零售商,也是美國商用在線主機(jī)服務(wù)的主要供應(yīng)商。此外它有也自己的消費(fèi)電子產(chǎn)品,即人們熟知的Kindle電子書。Kindle雖然是一款大膽的作品,但考慮到亞馬遜本身就是賣書起家,這一嘗試自然是可以理解的。現(xiàn)在,亞馬遜的Echo智能音箱和它的Alexa語音識別引擎又走進(jìn)了很多家庭,可以說亞馬遜在個(gè)人計(jì)算與通訊領(lǐng)域,已經(jīng)掀起了自史蒂夫·喬布斯發(fā)布iPhone以來的最重要的技術(shù)革命。 一開始,它只不過是個(gè)看似新奇的小玩意兒。2014年11月,亞馬遜發(fā)布了Echo智能音箱,它使用了人工智能技術(shù)來傾聽人類的提問。Echo會掃描聯(lián)網(wǎng)數(shù)據(jù)庫中的數(shù)百萬個(gè)單詞,不論你提出的問題是深邃還是淺顯,它都能給出答案。目前,Echo智能音箱的銷量已達(dá)到4700多萬臺,其用戶來自從阿爾巴尼亞到贊比亞的80多個(gè)國家,其服務(wù)器每天要回答用戶的1.3億多個(gè)問題。亞馬遜的語音識別引擎Alexa得名于亞歷山大港的古埃及圖書館,它可以按照用戶的要求播放音樂,提供天氣預(yù)報(bào)信息或體育比賽的得分,甚至可以遠(yuǎn)程調(diào)節(jié)用戶家里的室溫。它還會講笑話,回答一些瑣碎的問題,抖個(gè)機(jī)靈,或者開些無傷大雅的玩笑。(比如你可以讓它放個(gè)屁來聽聽)。 亞馬遜并沒有“發(fā)明”語音識別技術(shù),實(shí)際上語音識別技術(shù)已經(jīng)發(fā)明出來幾十年了。亞馬遜甚至并不是第一家提供主流語音識別應(yīng)用的科技巨頭。蘋果的Siri和谷歌語音助手的上市時(shí)間要比它早得多。微軟Cortana的發(fā)布基本上與Alexa在同一時(shí)期。但是隨著Echo的廣泛成功,語音識別領(lǐng)域的競爭驟然激烈了起來,各大科技廠商紛紛投下重注,試圖將這些“智能”家居設(shè)備變得跟PC甚至和智能手機(jī)一樣重要。正如谷歌的搜索引擎算法徹底改變了人們的信息消費(fèi)模式,進(jìn)而顛覆了整個(gè)廣告行業(yè)一樣,由人工智能技術(shù)驅(qū)動的語音識別技術(shù)也會推動類似的革命。亞馬遜Alexa部門的首席科學(xué)家羅希特·普拉薩德表示:“我們想抹平用戶使用互聯(lián)網(wǎng)時(shí)的不順暢,而最自然的方法就是聲音。Alexa不是那種一下子給你展示很多搜索結(jié)果,然后說‘選一個(gè)吧’的那種搜索引擎,而是會直接告訴你答案。” 各大科技廠商紛紛將人工智能與語音識別技術(shù)相結(jié)合,其目的遠(yuǎn)遠(yuǎn)不只是為了推出一款圣誕購物季最熱賣的小家電這么簡單。目前,谷歌、蘋果、Facebook和微軟等公司紛紛砸下重金研發(fā)競品。據(jù)投資公司Loup Ventures的分析師吉恩·蒙斯特估算,上述幾家科技巨頭每年在語音識別技術(shù)上的研發(fā)支出合計(jì)超過了50億美元,約占年度研發(fā)預(yù)算總額的10%。他認(rèn)為,語音識別技術(shù)的出現(xiàn)是計(jì)算領(lǐng)域的一個(gè)“具有重大意義的變化”。他認(rèn)為,語音指令很快將取代鍵盤和觸屏,成為“我們與互聯(lián)網(wǎng)交互的最常見的方式”。 隨著各大廠商紛紛投入重注,語音識別助手領(lǐng)域的競爭也變得愈發(fā)激烈。從研究公司Canalys提供的數(shù)據(jù)看,目前亞馬遜在這一領(lǐng)域暫時(shí)領(lǐng)先,它在全球聯(lián)網(wǎng)音箱市場上的份額達(dá)到了42%。谷歌的Home智能家居設(shè)備以34%的份額暫居亞軍,它搭載了谷歌自研的谷歌助手,據(jù)說近期的銷量已經(jīng)反超了亞馬遜。蘋果的HomePod價(jià)格最貴,加入戰(zhàn)局也是最晚,雖然市場占有率排名第三,但份額仍遠(yuǎn)遠(yuǎn)不如前面兩家。去年10月,F(xiàn)acebook也推出了自己的Portal系列影音設(shè)備,它們也具備部分語音識別功能。尤其值得注意的是,它搭載的也是亞馬遜的Alexa語音識別引擎。 |

FOUR SHORT YEARS AGO, Amazon was merely a ferociously successful online retailer and the dominant provider of online web hosting for companies. It also sold its own line of consumer electronics devices, including the Kindle e-reader, a bold but understandably complimentary outgrowth of its pioneering role as a next-generation bookseller. Today, thanks to the ubiquitous Amazon Echo smart speaker and its Alexa voice-recognition engine, Amazon has sparked nothing less than the biggest shift in personal computing and communications since Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone. It all seemed like such a novelty at first. In November 2014, Amazon debuted the Echo, a high-tech genie that uses artificial intelligence to listen to human queries, scan millions of words in an Internet-connected database, and provide answers from the profound to the mundane. Now, sales of some 47 million Echo devices later, Amazon responds to consumers in 80 countries, from Albania to Zambia, fielding an average of 130 million questions each day. Alexa, named for the ancient Egyptian library in Alexandria, can take musical requests, supply weather reports and sports scores, and remotely adjust a user’s thermostat. It can tell jokes; respond to trivia questions; and perform prosaic, even sophomoric, tricks. (Ask Alexa for a fart, if you must.) Amazon didn’t invent voice-recognition technology, which has been around for decades. It wasn’t even the first tech giant to offer a mainstream voice application. Apple’s Siri and Google’s Assistant predated Alexa by a few years, and Microsoft introduced Cortana around the same time as Alexa’s launch. But with the widespread success of the Echo, Amazon has touched off a fevered race to dominate the market for “smart” home devices by potentially making those objects as important as personal computers or even smartphones. Just as Google’s search algorithm revolutionized the consumption of information and upended the advertising industry, A.I.-driven voice computing promises a similar transformation. “We wanted to remove friction for our customers,” says Rohit Prasad, Amazon’s head scientist for Alexa, “and the most natural means was voice. It’s not merely a search engine with a bunch of results that says, ‘Choose one.’ It tells you the answer.” The powerful combination of A.I. with a new, voice-driven user experience makes this competition bigger than simply a battle for the hottest gadget offering come Christmastime—though it is that too. Google, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, and others are all pouring money into competing products. In fact, Gene Munster of the investment firm Loup Ventures estimates that the tech giants are spending a combined 10% of their annual research-and-development budgets, more than $5 billion in total, on voice recognition. He calls the advent of voice technology a “monumental change” for computing, predicting that voice commands, not keyboards or phone screens, are fast becoming “the most common way we interact with the Internet.” With the stakes so high, it’s no surprise the competition is fierce. Amazon holds an early lead, with 42% of the global market for connected speakers, according to research firm Canalys. Google is making itself heard too. Its Echo look-alike line of Google Home devices powered by its Google Assistant has a 34% share and recently has been outselling Amazon. The pricey and later-to-the-game Apple HomePod is a distant third. And in October, Facebook unveiled its line of Portal audio and video devices, which do some but not all of the voice-recognition tasks of its mega-cap competitors—and, notably, is powered by Alexa. |

|

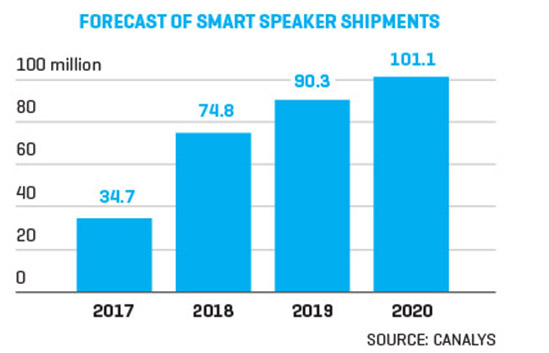

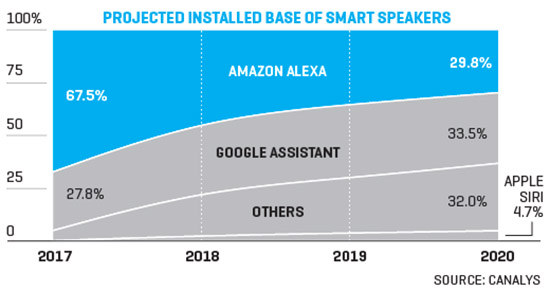

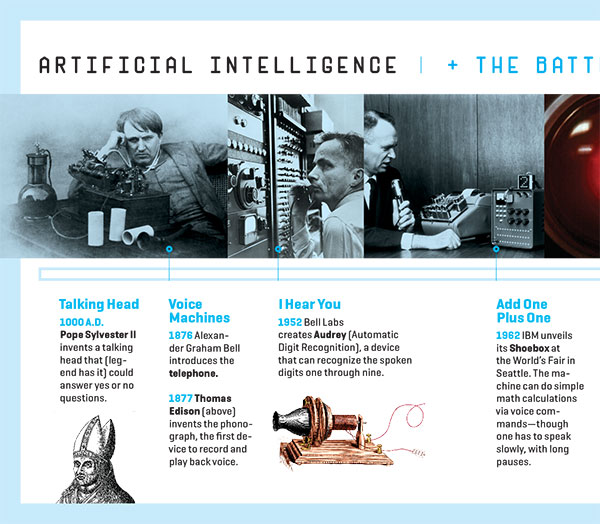

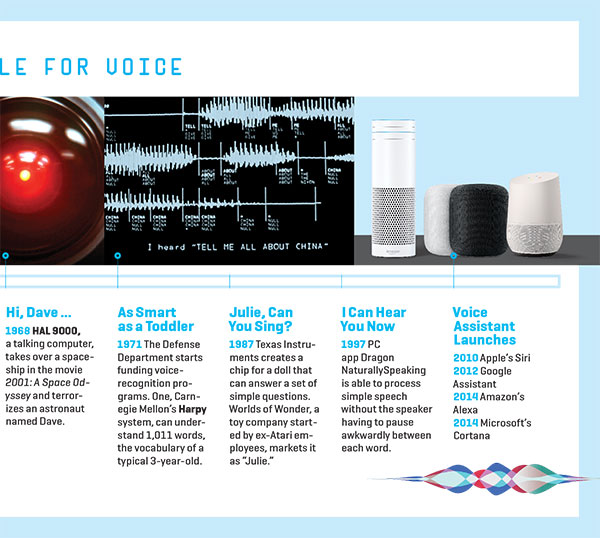

當(dāng)前,聯(lián)網(wǎng)智能音箱以及類似設(shè)備的市場規(guī)模已然不小,而且還在繼續(xù)增長。不過對于這些科技巨頭來說,語音識別技術(shù)的價(jià)值遠(yuǎn)遠(yuǎn)超過這些設(shè)備本身。據(jù)市場研究機(jī)構(gòu)全球市場觀察公司(Global Market Insights)的研究,2017年,全球智能音箱市場的銷售額是45億元,預(yù)計(jì)到2024年將增長至300億美元。不過這幾家科技巨頭顯然并不在乎賣硬件的這點(diǎn)小錢,比如亞馬遜基本是在將Echo保本甚至虧本銷售。在去年歐美地區(qū)的假日購物季期間,亞馬遜推出了迷你版的Echo Dot音箱,售價(jià)只有29美元,ABI研究公司認(rèn)為這個(gè)價(jià)格甚至還要低于它的零部件成本。各大廠商之所以肯做賠本生意,就是為了把用戶鎖定在他們的其它產(chǎn)品和服務(wù)上。比如亞馬遜就是要通過Echo產(chǎn)品提高亞馬遜Prime訂閱服務(wù)的價(jià)值。谷歌則寄希望于語音搜索功能能夠引來更多的廣告收入。蘋果則希望以語音識別技術(shù)為工具,將手機(jī)、電腦、電視遙控器甚至是車載軟件整合在一塊,打造一體化的體驗(yàn)。 由于語音識別領(lǐng)域已經(jīng)吸引了這么多的投資,而且還在快速創(chuàng)新,因此現(xiàn)在預(yù)測誰是贏家還為時(shí)過早。但有一點(diǎn)大家已經(jīng)形成了共識,那就是有了人工智能加成的語音識別技術(shù),必然將向今天的智能手機(jī)一樣,成為我們訪問互聯(lián)網(wǎng)的新用戶界面。另外,語音識別技術(shù)也將降低人們使用科技的門檻,促進(jìn)科技的普及。谷歌公司負(fù)責(zé)谷歌助手與搜索業(yè)務(wù)的產(chǎn)品與設(shè)計(jì)的副總裁尼克·福克斯表示:“它讓那些不太識字的人也能使用這個(gè)系統(tǒng)。另外,人們在開車的時(shí)候也可以使用它,做飯的時(shí)候也可以用它來聽菜譜。每過一段時(shí)間,科技就會發(fā)生一次結(jié)構(gòu)性的轉(zhuǎn)變。我們認(rèn)為,語音識別就是這樣一種轉(zhuǎn)變。” 雖然如此,但今天的語音識別技術(shù)仍然處于比較早期的階段。它的應(yīng)用還比較初級,而且它也有一些比較大的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)因素。比如科技公司會不會利用它對用戶進(jìn)行竊聽,以及科技公司通過收集公民的語音數(shù)據(jù)又攫取了多少權(quán)力,人們對這些問題都存在著合理的擔(dān)憂。華盛頓大學(xué)電氣工程學(xué)教授、世界頂級的語音和語言技術(shù)科學(xué)家瑪麗·奧斯坦多夫表示:“有了人工智能語音識別技術(shù),我們就好比從螺旋槳飛機(jī)進(jìn)入了噴氣式飛機(jī)時(shí)代。”她指出,現(xiàn)在的語音識別技術(shù)已經(jīng)能夠很好地回答那些直截了當(dāng)?shù)膯栴},但在真實(shí)語境的對話中,表現(xiàn)得仍然令人失望。“在能識別多少個(gè)單詞、聽懂多少個(gè)指令上,人工智能語音識別技術(shù)表現(xiàn)得非常出色。但我們畢竟還沒進(jìn)入火箭時(shí)代。” 幾十年來,科技行業(yè)一直堅(jiān)信,語音識別技術(shù)必將成為下一個(gè)“殺手級應(yīng)用”。早在上世紀(jì)50年代,貝爾實(shí)驗(yàn)室就開發(fā)了一個(gè)名為奧黛麗(Audrey)的系統(tǒng),它可以識別從1到9的語音數(shù)字。20世紀(jì)90年代時(shí)已經(jīng)有了一款名叫Dragon NaturallySpeaking的PC軟件,它可以實(shí)現(xiàn)簡單的語音識別功能,而不需要說話者每說完一個(gè)單詞就尷尬地停頓一會兒。但直到蘋果公司2010年在iPhone上發(fā)布了Siri語音助手,消費(fèi)者才意識到一個(gè)擁有強(qiáng)大計(jì)算能力的語音識別引擎能做哪些事。大約就在同一時(shí)間段,亞馬遜這樣一家充滿了《星際迷航》式幻想的公司(它的老板杰夫·貝佐斯也是一個(gè)正牌《星際》迷)開始暢想,能不能將企業(yè)號星際飛船上的那種會說話的電腦變成現(xiàn)實(shí)。亞馬遜公司的普拉薩德曾發(fā)表過上百篇關(guān)于語音識別人工智能及相關(guān)話題的科學(xué)文章,他表示:“在我們的暢想中,未來你可以通過語音與任何服務(wù)交互。”而Alexa就是為此而生的。它是一臺多才多藝的設(shè)備,可以讓消費(fèi)者更容易地與亞馬遜進(jìn)行交互。 隨著語音識別技術(shù)的進(jìn)步——也就是計(jì)算速度越來越快,價(jià)格越來越便宜,越來越普及,因此日益主流化——亞馬遜、谷歌、蘋果等科技廠商也得以更容易地建立一個(gè)無縫的網(wǎng)絡(luò),利用語音識別技術(shù),將智能家居設(shè)備與他們旗下的其他系統(tǒng)連接起來。比如蘋果CarPlay的用戶下班路上可以告訴Siri,別忘了在蘋果電視上下載最新一集的《權(quán)力的游戲》,然后讓HomePod等我一回家就開始播放。兩年前,谷歌也發(fā)布了基于語音識別技術(shù)的智能家居產(chǎn)品Home,它將谷歌的音樂服務(wù)(YouTube)和最新款的Pixel系列手機(jī)和平板產(chǎn)品結(jié)合在了一起。換言之,每個(gè)科技巨頭都將語音識別技術(shù)當(dāng)作了連接其多個(gè)數(shù)碼產(chǎn)品的紐帶。 上述幾個(gè)科技巨頭個(gè)個(gè)都有超強(qiáng)的盈利能力,因此他們都有充足的資金來搞研究和營銷,最終拿出的產(chǎn)品也各不相同。蘋果和谷歌都有自己的移動操作系統(tǒng),也就是說,iPhone和所有的安卓手機(jī)在出廠時(shí)就已預(yù)裝了Siri或谷歌助手。相比之下,亞馬遜就得說服用戶將Alexa應(yīng)用下載到他們的iPhone或安卓手機(jī)上了。前華爾街分析師蒙斯特認(rèn)為:“要打開Alexa語音識別應(yīng)用,就要比Siri和谷歌助手多花一步,這對亞馬遜是一個(gè)明顯的劣勢。” 而相比之下,Siri和谷歌助手只需用戶喊一聲它們的名字就能激活。 不過,iOS和Android是面向所有第三方開發(fā)者的,而Alexa應(yīng)用同時(shí)兼容這兩個(gè)平臺,也就是說,兩個(gè)平臺上的開發(fā)者都可以寫Alexa的程序。亞馬遜CEO杰夫·貝佐斯今年早些時(shí)候曾在一次財(cái)報(bào)發(fā)布會上稱:“有來自150多個(gè)國家的數(shù)萬名開發(fā)者”都在構(gòu)建Alexa的應(yīng)用程序,并將它們集成到非亞馬遜的設(shè)備里。而合作伙伴也是各大語音識別應(yīng)用競爭的一個(gè)競爭戰(zhàn)場。現(xiàn)在,Sonos公司的“電聲棒”、Jabra公司的耳機(jī),以及寶馬、福特、豐田等公司的汽車都已用上了Alexa。谷歌的語音識別程序則被集成到了索尼、鉑傲的音響、August公司的智能門鎖和飛利浦的LED照明系統(tǒng)上。蘋果的HomPod則與First Alert公司的安全防衛(wèi)系統(tǒng)和霍尼韋爾公司的智能恒溫器進(jìn)行了合作。谷歌副總裁尼克斯表示:“這些合作的好處是將語音識別功能整合到了整個(gè)智能家居生態(tài)系統(tǒng),我不用打開手機(jī)也能使用應(yīng)用程序了。我只要說一聲:‘讓我看看誰在門口’,門前的監(jiān)控視頻就會自動顯示出來。總之,它通過統(tǒng)一實(shí)現(xiàn)了簡化。” 人工智能一直是反烏托邦文化里的常客,特別是在《終結(jié)者》和《黑客帝國》系列電影里,智能機(jī)器人甚至造了人類的反,將人類逼到了“亡球滅種”的邊緣。不過慶幸的是,現(xiàn)在的我們離被機(jī)器人奴役還有很遠(yuǎn)。不過人工智能技術(shù)的進(jìn)步,以及廉價(jià)計(jì)算設(shè)備的普及,已經(jīng)讓很多具有科幻感的構(gòu)思成為了現(xiàn)實(shí)。早期的語音識別程序雖然也不錯,但也沒有超過編寫它們的程序員的最高水平。但現(xiàn)在這些應(yīng)用卻變得越來越好了,這是因?yàn)樗鼈兺ㄟ^互聯(lián)網(wǎng)與數(shù)據(jù)中心連接,而且科技公司花了好幾年時(shí)間,用大量數(shù)據(jù)對這些算法進(jìn)行“訓(xùn)練”,使其學(xué)會了識別不同的語言模式。現(xiàn)在,這些人工智能語音識別應(yīng)用不僅能識別單詞、方言和俗語,甚至還能根據(jù)上下文分析語義(比如通過分析呼叫中心的客服代表與客戶的電話錄音,或者分析用戶與數(shù)字助手的互動)。 |

The current market for connected speakers and similar gadgets is big and growing—but not necessarily the most dramatic voice-related opportunity for the tech titans. Global Market Insights, a research firm, pegs global 2017 smart-speaker sales at $4.5 billion, a number it projects will grow to $30 billion by 2024. The hardware revenues, however, are largely beside the point. Amazon, for example, has sold the Echo at breakeven or less. Last holiday season it offered the bare-bones Echo Dot for $29, which ABI Research reckons is less than the cost of the device’s parts. Instead, each major player has a strategy that in some way feeds its larger goal of locking in customers to its other goods and services. Amazon, for one, uses the Echo line to increase the value of its Amazon Prime subscription service. Google hopes voice searches will eventually boost the already massive trove of data that feeds its advertising franchise. With Siri, Apple sees a way to tie together its phones, computers, TV controllers, and even the software that automakers are tying into their onboard systems. It’s too soon to predict a winner, what with all the investment and fast-moving innovations. But it’s safe to say the industry has coalesced around the notion that voice technology, enhanced by recent advancements in artificial intelligence, is the user interface of tomorrow. And it promises to have a democratizing impact on an industry that has separated novices from experts. “Voice enables all kinds of things,” says Nick Fox, a Google vice president who oversees product and design for the Google Assistant and Search. “It enables people who are less literate to use the system. It enables people who are driving. It enables people while cooking to hear a recipe. Every once in a while there is a tectonic shift in technology, and we think voice is one of those.” For all that, voice recognition remains in its infancy. Its applications are rudimentary compared with where researchers expect them to go, and there’s a significant ick factor associated with voice. Legitimate concerns linger as to how much the tech companies are eavesdropping on their customers—and how much power they are accumulating in the form of data derived from the spoken information they are collecting. “With A.I. voice recognition, we’ve gone from the age of the biplane to the age of the jet plane,” says Mari Ostendorf, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Washington and one of the world’s top scientists on speech and language technology. She notes that computers have gotten good at answering straightforward questions but still are relatively hopeless when it comes to actual dialogue. “It’s truly impressive what Big Tech has done in terms of how many words voice A.I. can now recognize and the number of commands it can understand. But we’re not in the rocket era yet.” VOICE RECOGNITION HAS BEEN the next killer app for decades. In the 1950s, Bell Labs created a system called Audrey that could recognize the spoken digits one through nine. In the 1990s, PC users installed Dragon NaturallySpeaking, a program that could process simple speech without the speaker having to pause awkwardly after each word. But it wasn’t until Apple unleashed Siri on the iPhone in 2010 that consumers got a sense of what a voice-recognition engine tied to massive computing power could accomplish. Around the same time, Amazon, a company full of Star Trek aficionados—and led by a true Trekkie in CEO Jeff Bezos—began dreaming about replicating the talking computer aboard the Starship Enterprise. “We imagined a future where you could interact with any service through voice,” says Amazon’s Prasad, who has published more than 100 scientific articles on conversational A.I. and other topics. The result was Alexa, a multifaceted device designed to let consumers communicate more easily with Amazon. As voice recognition improves—which it does as computing power gets faster, cheaper, more ubiquitous, and thus more mainstream—Amazon, Google, Apple, and others can more easily build a seamless network where voice links their smart home devices with other systems. It’s possible for Apple CarPlay users, for example, to tell Siri on the drive home to slot the latest episode of Game of Thrones as “up next” on their Apple TV and to command their HomePod to play it once they’ve arrived. Two years ago, Google released its voice-enabled Home that ties together its music offerings, YouTube, and its latest Pixel phones and tablets. Each tech giant, in other words, sees voice as a tether to the myriad digital products it is creating. The combatants, each wildly profitable and therefore able to fund ample research and marketing efforts, bring different assets to the table. Apple and Google, for example, own the two dominant mobile operating systems, iOS and Android, respectively. That means Siri and Google Assistant come preinstalled on nearly all new phones. Amazon, in contrast, needs to get consumers to install and then open the Alexa app on their iPhones or Android devices. “The extra step to open the Alexa voice app puts Amazon at a distinct disadvantage,” says Loup’s Munster, formerly a Wall Street analyst of computer companies. By contrast, all that’s required to activate Siri and the Google Assistant is to say their names. That said, iOS and Android are open to third-party developers of all stripes, and Amazon is one of them?—meaning that nothing is stopping developers on both platforms from writing Alexa programs. Bezos bragged in an earnings release earlier this year that “tens of thousands of developers across more than 150 countries” are building Alexa apps and incorporating them into non-Amazon devices. Indeed, partnerships are a key battleground for voice applications. Alexa is built into “soundbars” from Sonos, headphones from Jabra, and cars from BMW, Ford, and Toyota. Google boasts integrations with audio equipment makers Sony and Bang & Olufsen, August smart locks, and Philips LED lighting systems, and Apple has partnerships that allow its HomePod to work with First Alert Security systems and Honeywell smart thermostats. “The beauty of these partnerships,” says Google’s Fox, “is that they allow us to link voice into the whole smart-appliance ecosystem. I don’t have to open my phone and go to an app. I can just say to the device, ‘Show me who’s at my front door,’ and it will pop right up. It’s simplifying by unifying.” Artificial intelligence has long been a staple of dystopian popular culture, notably from films such as The Terminator and The Matrix, where wickedly clever machines rise up and pose a threat to humankind. Thankfully, we’re not there yet, but advances in A.I. and the availability of cheap computing have made impressively futuristic applications a reality. Early voice-recognition programs were only as good as the programmers who wrote them. Now these apps keep getting better because they are connected through the Internet to data centers. These complex mathematical models sift through huge amounts of data that companies have spent years compiling and learn to recognize different speech patterns. They can recognize vocabulary, regional accents, colloquialisms, and the context of conversations by analyzing, for example, recordings of call-center agents talking with customers or interactions with a digital assistant. |

|

語音識別系統(tǒng)既依賴于計(jì)算機(jī)科學(xué),也依賴于物理學(xué)。語音會產(chǎn)生空氣振動,語音引擎則會接受模擬聲波,然后將其轉(zhuǎn)換成數(shù)字格式,計(jì)算機(jī)就會分析這些數(shù)據(jù)的意義,而人工智能則能夠加快這一過程。人工智能首先要搞清楚它收到的語音是不是指向它的系統(tǒng)的,因此它首先要檢測客戶選定的“喚醒詞”,比如“Alexa”。然后,系統(tǒng)會使用機(jī)器學(xué)習(xí)模型,對所接受的數(shù)據(jù)進(jìn)行猜測。由于這個(gè)模型已經(jīng)用幾百萬個(gè)用戶貢獻(xiàn)的語料庫訓(xùn)練過,因此猜測的準(zhǔn)確度是很高的。谷歌助手的工程副總裁約翰·斯考威克解釋道:“語音識別系統(tǒng)首先會識別聲音,然后會把這句話放到語境中去理解。比如說,如果我說了一句:‘天氣怎么樣?’系統(tǒng)就知道,我所指的是一個(gè)國家或一個(gè)城市的天氣。我們的數(shù)據(jù)庫中有500萬個(gè)單詞的英文詞匯,如果不結(jié)合語境,從500萬個(gè)單詞中識別出一個(gè)詞是極其困難的。但如果人工智能知道你問的是一個(gè)城市的情況,那么這就把范圍縮小到了三萬分之一,這樣猜中就簡單多了。” 有了強(qiáng)大的計(jì)算能力,系統(tǒng)就有了很多學(xué)習(xí)的機(jī)會。舉個(gè)真實(shí)的例子,為了讓Alexa打開家里的微波爐,語音識別引擎首先要理解這個(gè)指令。也就是說,它得能夠聽懂各州各省的方言,小孩子的高調(diào)門兒,或者是老外的怪腔怪調(diào)。與此同時(shí),它還要過濾廣播、音樂等無關(guān)的背景音。然后,人們使用微波爐時(shí)的指令也是不一樣的。有人可能會說:“把我的飯重新熱一下”;有人則可能說:“打開微波爐”或“用微波爐把飯熱兩分鐘。”Alexa這種語音識別應(yīng)用會將用戶的問題與數(shù)據(jù)庫中的類似指令進(jìn)行對比,從而明白“把我的飯重新熱一下”也是用戶有可能下的指令。 語音識別技術(shù)之所以近來大受歡迎,也是由于它在將人類指令轉(zhuǎn)化為行動方面表現(xiàn)得相當(dāng)出色。谷歌公司的斯考威克表示,谷歌的語音識別引擎已經(jīng)能達(dá)到95%的準(zhǔn)確率,比2013年的80%有了明顯提高,幾乎與人類的理解能力不相上下了。近來該領(lǐng)域的一個(gè)重大成績是語音識別引擎已經(jīng)學(xué)會了如何過濾背景噪音。不過只有當(dāng)用戶的指令或問題比較簡單時(shí),系統(tǒng)才能達(dá)到這樣高的識別率——比如問它:“最新的《諜中諜6》什么時(shí)候上映?”如果你就某件事征求Alexa或谷歌助手的意見,或是試圖跟它進(jìn)行一場拉鋸式的談話,系統(tǒng)就要么會給出一個(gè)預(yù)先編程好的幽默答案,要么直接提出抗議:“我不知道怎么回答。” 在消費(fèi)者看來,語音識別設(shè)備不僅實(shí)用,有時(shí)也能給人帶來快樂。而在制造它們的科技巨頭看來,語音識別設(shè)備雖小,但是極為高效的收集數(shù)據(jù)者。大約60%的亞馬遜Echo和谷歌Home的用戶至少將語音助手與一種智能家居設(shè)備相連(比如恒溫器、安全系統(tǒng)等),而這些智能家居設(shè)備可以透露關(guān)于用戶生活的無數(shù)細(xì)節(jié)。對于亞馬遜、谷歌和蘋果這些公司,他們收集的數(shù)據(jù)越多,就能更好地服務(wù)消費(fèi)者——不管是通過附加服務(wù)、訂閱服務(wù),還是代表其他商家打廣告。 這個(gè)領(lǐng)域的商機(jī)也是顯而易見的。一位消費(fèi)者只要將Echo與恒溫器相連,那么如果他看到了智能照明系統(tǒng)的廣告,就也會傾向于購買。如果你對隱私特別在意,你或許會覺得被“竊聽”的感覺很不舒服。但借助這項(xiàng)技術(shù),科技巨頭們已經(jīng)坐擁了海量個(gè)人數(shù)據(jù),反過來這些數(shù)據(jù)也使他們能更有效地向消費(fèi)者進(jìn)行營銷。 這幾家科技巨頭的總體戰(zhàn)略各不相同,對收集來的數(shù)據(jù)的使用方式也略有差異。亞馬遜表示,Alexa收集來的數(shù)據(jù)主要用于該軟件的后續(xù)研發(fā),以使它變得更加智能,對用戶更加實(shí)用。亞馬遜稱,Alexa進(jìn)化得越好,用戶就會越能看到亞馬遜的產(chǎn)品和服務(wù)的價(jià)值——包括它的Prime會員計(jì)劃。盡管亞馬遜也在大力推動廣告業(yè)務(wù)(市場研究機(jī)構(gòu)eMarketer認(rèn)為,2018年亞馬遜的數(shù)字廣告業(yè)務(wù)收入將達(dá)到46.1億美元),但亞馬遜的一位發(fā)言人表示,公司目前不會利用Alexa的數(shù)據(jù)賣廣告。谷歌雖然擁有龐大的廣告業(yè)務(wù),卻也一反常態(tài)地表示,不會使用語音識別技術(shù)收集的數(shù)據(jù)賣廣告。蘋果向來號稱不愿利用顧客數(shù)據(jù)換取商業(yè)利益,此次自然也不例外,蘋果表示,該公司從語音識別技術(shù)中獲取的用戶數(shù)據(jù)將僅僅用于改善用戶體驗(yàn)——以及銷售更多昂貴的HomePod設(shè)備。 雖然亞馬遜是做購物起家的,但大多數(shù)用戶并未使用語音識別設(shè)備幫助他們購物。亞馬遜不愿透露有多少Echo的用戶用它購物,不過咨詢機(jī)構(gòu)Codex集團(tuán)最近對網(wǎng)購圖書者的一項(xiàng)調(diào)查顯示,只有8%的用戶通過Echo買過書,有13%的用戶通過它聽過電子書。研究機(jī)構(gòu)Canalys的分析師文森特·蒂爾克表示:“人是習(xí)慣性動物,如果你想買一個(gè)咖啡杯,你很難對智能音箱描述出你喜歡的杯子的樣式。” 亞馬遜表示,公司并未過分關(guān)注Echo作為購物助手的作用,不過它仍然希望亞馬遜的智能家居設(shè)備能反哺公司的零售業(yè)務(wù)。亞馬遜的自然語言處理科學(xué)家普拉薩德表示:“人總是根據(jù)以前的購物習(xí)慣去購物。如果你想買幾節(jié)電池,這種東西,你既不需要親眼去挑,也不需要記住買一種。如果以前你從沒買過電池,我們當(dāng)然會建議你買亞馬遜品牌的。” 語音助手在購物上的作用遠(yuǎn)遠(yuǎn)不止買幾節(jié)電池。目前,很多商家都想跟這些科技巨頭合作,并利用這些平臺。據(jù)OC&C戰(zhàn)略咨詢公司預(yù)測,到2022年,語音識別購物的銷售額將從現(xiàn)在的20億美元增長至400億美元。現(xiàn)在,有幾款智能家居設(shè)備的迭代產(chǎn)品已經(jīng)展現(xiàn)了這個(gè)潛力。比如亞馬遜和谷歌都推出了帶屏幕的智能家居設(shè)備,它們看起來有點(diǎn)像小型電腦和電視機(jī)的跨界產(chǎn)品,因此更適合用來網(wǎng)購。2017年春天,亞馬遜推出了230美元的Echo Show。跟其他Echo設(shè)備一樣,Echo Show也內(nèi)置了Alexa應(yīng)用,但用戶也能通過它看到圖像。這樣一來,消費(fèi)者就可以看見自己想買的商品和購物清單了。同時(shí),用戶也可以用它來看電視、聽音樂、看監(jiān)控視頻、旅行照片等等。而在做這些的時(shí)候,用戶無需點(diǎn)擊任何一個(gè)按鍵,也完全不需要操縱鼠標(biāo)。 谷歌已經(jīng)與四家消費(fèi)電子廠商展開了合作,有些廠商最近已經(jīng)開售安裝了谷歌助手的智能屏產(chǎn)品。比如聯(lián)想的Smart Display智能顯示器看起來很像Facebook的Portal產(chǎn)品,零售價(jià)為250美元,與JBL的Link View設(shè)備相同。LG也計(jì)劃推出搭載谷歌助手的ThinQ View設(shè)備。今年10月,谷歌也開始銷售自己Home Hub設(shè)備了,該設(shè)備搭載了一塊7寸顯示屏,售價(jià)為149美元。 從長遠(yuǎn)來看,谷歌認(rèn)為,擁有屏幕將使語音購物變得更容易。谷歌并不像亞馬遜那樣直接銷售產(chǎn)品,但它的“谷歌購物”網(wǎng)站卻將零售商與谷歌搜索引擎直接相連。目前,谷歌已經(jīng)將Home設(shè)備打造成一個(gè)購物工具了。比如谷歌與星巴克有合作,用戶只需要告訴谷歌助手點(diǎn)一杯“老樣子”,飲品就會自動送上門。去年,谷歌還鞏固了與全球最大零售商沃爾瑪?shù)暮献麝P(guān)系。用戶可將沃爾瑪賬戶與谷歌購物網(wǎng)站相連,這樣通過谷歌的Home設(shè)備,用戶即可檢查附近的沃爾瑪門店里有沒有自己喜歡的運(yùn)動鞋,或是預(yù)訂一臺平板電視當(dāng)日提取。如果你不知道離你最近的沃爾瑪在哪兒,它也能幫你找到。 而視覺識別技術(shù)(它可以看作是人工智能語音識別技術(shù)的小弟,這種技術(shù)早就被用來在人群中對比罪犯了)的興起,將使人們在這些設(shè)備上購物變得更加便利。今年9月,亞馬遜宣布,它正在用Snapchat相機(jī)測試一款新應(yīng)用。消費(fèi)只要用Snapchat的相機(jī)拍下某個(gè)產(chǎn)品或者條形碼的照片,就能在屏幕上看到亞馬遜的產(chǎn)品頁面。不難想象,要不了多久,用戶就能在他們Echo Show上實(shí)現(xiàn)類似功能,到時(shí)候用戶不光能看見產(chǎn)品的價(jià)格和評價(jià),估計(jì)還能看見該產(chǎn)品是否支持Prime的兩天免費(fèi)快遞上門服務(wù)。 雖然這項(xiàng)技術(shù)的前景令人興奮,可是對那些對高科技不敏感的人來說,他們可能得花一些時(shí)間,才能習(xí)慣跟機(jī)器對話。現(xiàn)在很多科技公司的社會公信力不高,他們必須得讓消費(fèi)者相信,這些設(shè)備并不是在出于邪惡的原因在竊聽他們。實(shí)際上,智能揚(yáng)聲器只有檢測到“喚醒詞”才會切換到對話模式,比如“Alexa”或者“Hey Google”。今年5月,亞馬遜不小心將一位波特蘭市的高管與他妻子關(guān)于地板的一段對話發(fā)送給了他的一名員工。亞馬遜對此次事故公開道歉,并表示它“曲解”了這段對話。 口頭指令的出錯可能要遠(yuǎn)遠(yuǎn)超過打字輸入的命令。有些時(shí)候,你甚至可能為此付出代價(jià)。比如去年,達(dá)拉斯的一個(gè)6歲的小女孩在跟Alexa討論餅干和玩偶等話題。幾天后,快遞員就給她家送來了4磅餅干和一個(gè)價(jià)值170美元的玩偶。亞馬遜表示,Alexa是有家長控制功有的,如果啟用了該功能,這次事故本不會發(fā)生。 不管怎樣,人工智能語音識別的大規(guī)模采用很可能會是自然而然的事,畢竟它給我們帶來了更多的便利。目前,全球的人工智能語音識別設(shè)備已經(jīng)超過1億臺,語音成為人與機(jī)器的主要交互媒介只不過是個(gè)時(shí)間問題——哪怕有時(shí)這種對話只是毫無營養(yǎng)的惡搞和尬笑。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng)) 本文作者布萊恩·杜梅因撰寫的關(guān)于亞馬遜的一本新書即將由斯克里布納出版社出版。 本文原載于2018年11月1日刊的《財(cái)富》雜志。 譯者:樸成奎 |

Voice-recognition systems rely as much on physics as on computer science. Speech creates vibrations in the air, which voice engines pick up as analog sound waves and then translate into a digital format. Computers can then analyze that digital data for meaning. Artificial intelligence turbocharges the process by first figuring out whether the sound is directed toward its systems by detecting a customer-chosen “wake word” such as “Alexa.” Then they use machine-learning models trained by what millions of other customers have said to them before to make highly accurate guesses as to what was said. “A voice-recognition system first recognizes the sound, and then it puts the words in context,” explains Johan Schalkwyk, an engineering vice president for the Google Assistant. “If I say, ‘What’s the weather in?…,’ the A.I. knows that the next word is a country or a city. We have a 5-million-word English vocabulary in our database, and to recognize one word out of 5 million without context is a super hard problem. If the A.I. knows you’re asking about a city, then it’s only a one-in-30,000 task, which is much easier to get right.” Computing power allows the systems multiple opportunities to learn. In order to ask Alexa to turn on the microwave—a real example—the voice engine first needs to understand the command. That means learning to decipher thick Southern accents (“MAH-?cruhwave”), high-pitched kids’ voices, non?-native speakers, and so on, while at the same time filtering out background noise like song lyrics playing on the radio. It then has to understand the many ways people might ask to use the microwave: “Reheat my food,” “Turn on my microwave,” “Nuke the food for two minutes.” Alexa and other voice assistants match questions with similar commands in the database, thereby “l(fā)earning” that “reheat my food” is how a particular user is likely to ask in the future. The technology has taken off in part because it has gotten so proficient at translating human commands into action. Google’s Schalkwyk says his company’s voice engine now responds with 95% accuracy, up from only 80% in 2013—about the same so-so level of accuracy human listeners achieve. One of the great recent triumphs in the field has been teaching the engines to filter out nonspoken background noise, a distraction that can frustrate the keenest human ear. These systems reach this level, however, only when the question is simple, like, “What time is Mission: Impossible playing?” Ask the Google Assistant or Alexa for an opinion or try to have an extended back-and-forth conversation, and the machine is likely to give either a jokey preprogrammed answer or to simply demur: “Hmm, I don’t know that one.” TO CONSUMERS, voice-driven gadgets are helpful and sometimes entertaining “assistants.” For the tech giants that make them—and keep them connected to the computers in their data centers—they’re tiny but extremely efficient data collectors. About 60% of Amazon Echo and Google Home users have at least one household accessory, such as a thermostat, security system, or appliance, connected to them, according to Consumer Intelligence Research Partners. A voice-powered home accessory can record endless facts about a user’s daily life. And the more data Amazon, Google, and Apple can accumulate, the better they can serve those consumers, whether through additional devices, subscription services, or advertising on behalf of other merchants. The commercial opportunities are straightforward. A consumer who connects an Echo to his thermostat might be receptive to an offer to buy a smart lighting system. Creepy though it may sound to privacy advocates, the tech giants are sitting on top of a treasure trove of personal data, the better with which to market more efficiently to consumers. As with their overall strategies, the tech giants have different approaches to the data they collect. Amazon says it uses data from Alexa to make the software smarter and more useful to its customers. The better Alexa becomes, the company claims, the more customers will see the value of its products and services, including its Prime membership program. Although Amazon is making a big push into advertising—the research firm eMarketer projects the company will pull in $4.61 billion from digital advertising in 2018—a spokesperson says it does not currently use Alexa data to sell ads. Google, counterintuitively, considering its giant ad business, also isn’t positioning voice as an ad opportunity—yet. Apple, which loudly plays up the virtue of its unwillingness to exploit customer data for commercial gain, claims to be approaching voice merely as a way to improve the experience of its users and to sell more of its expensive HomePods. DESPITE ONE OF AMAZON’S early selling points, what people aren’t asking their devices to do is help them shop. Amazon won’t comment on how many Echo users shop with the device, but a recent survey of book buyers by consulting firm the Codex Group suggests that it’s still early days. It found that only 8% used the Echo to buy a book, while 13% used it to listen to audiobooks. “People are creatures of habit,” says Vincent Thielke, an analyst with research firm Canalys, which focuses on tech. “When you’re looking to buy a coffee cup, it’s hard to describe what you want to a smart speaker.” Amazon does say it’s not overly fixated on the Echo as a shopping aid, especially given how the device ties in with the other services it offers through its Prime subscription. Still, it holds out hope the Amazon-optimized computers it has placed in customers’ homes will boost its retail business. “What is available for shopping is your buying history,” says Amazon’s Prasad, the natural-language-processing scientist. “If you want to buy double-A batteries, you don’t need to see them, and you don’t need to remember which ones. If you’ve never bought batteries before, we will suggest Amazon’s brand, of course.” The potential to boost shopping remains far bigger than selling replacement batteries, especially because so many merchants will want to partner with—and take advantage of—the platforms associated with the tech giants. The research firm OC&C Strategy Consultants predicts that voice shopping sales from Echo, Google Home, and their ilk will reach $40 billion by 2022—up from $2 billion today. A critical evolution of the speakers helps explain the promise. Both Amazon and Google now offer smart home devices with screens, which make the gadgets feel more like a cross between small computers and television sets and thus better for online shopping. Amazon launched the $230 Echo Show in the spring of 2017. Like other Echo devices, the Show has ?Alexa embedded, but it also enables users to see images. That means shoppers can see the products they are ordering as well as their shopping lists, TV shows, music lyrics, feeds from security cameras, and photos from that vacation in Montana, all without pushing any buttons or manipulating a computer mouse. For its part, Google has partnered with four consumer electronics manufacturers, some of which have recently started selling smart screens integrated with the Google Assistant. The Lenovo Smart Display, for example, looks a lot like Facebook’s new Portal and retails for $250, the same price as the JBL Link View. LG plans to launch the ThinQ View. In October, Google started selling its own version, the Home Hub, for $149, with a seven-inch screen. In the long run, Google is betting that having a screen will make voice shopping easier. The search company doesn’t sell products directly like Amazon, but its Google Shopping site connects retailers to the Google search engine. Already it is empowering the Google Home device as a shopping tool. It has a partnership with Starbucks, for example, that enables a user to tell the Google Assistant to order “my usual,” and the order will be ready upon arrival. Last year, Google cemented a partnership with Walmart, the world’s largest retailer. Shoppers can link their existing Walmart online account to Google’s shopping site and simply ask Google Home to check whether a favorite pair of running shoes is in stock, reserve a flat-screen TV for same-day pickup, or find the nearest Walmart store. The rise of vision-recognition tech—voice recognition’s A.I. sibling, long used for matching faces of criminals in a crowd—will make shopping on these devices even more convenient. In September, Amazon announced it was testing with Snapchat an app that enables shoppers to take a picture of a product or a bar code with Snapchat’s camera and then see an Amazon product page on the screen. It’s not hard to imagine that the next step for shoppers will be to use the camera embedded in the Echo Show to snap a picture of something they’d like to buy and then see onscreen the same or similar items along with prices, ratings, and whether they’re available for Prime two-day free shipping. EXCITING AS THIS technology is, it may take non?technophiles a bit of time to get used to speaking to machines. The tech giants aren’t the most trusted of companies right now, and they’ll need to convince consumers their devices aren’t eavesdropping for nefarious reasons. Smart speakers are supposed to click into listen mode only when they detect “wake words,” such as “Alexa,” or “Hey, Google.” In May, Amazon mistakenly sent a conversation about hardwood floors that a Portland executive was having with his wife to one of his employees. Amazon publicly apologized for the snafu, saying it had “misinterpreted” the conversation. The spoken word has the potential for errors far beyond that of typed commands. This can have commercial repercussions. Last year a 6-year-old Dallas girl was talking to Alexa about cookies and dollhouses, and days later, four pounds of cookies and a $170 dollhouse were delivered to her family’s door. Amazon says Alexa has parental controls that, if used, would have prevented the incident. Still, widespread adoption is likely because of the growing convenience of a voice-?connected world. With more than 100 million of these devices already installed and in listening mode, it’s only a matter of time before voice becomes the dominant way humans and machines communicate with each other—even if the conversation involves little more than scatological sounds and squeals of laughter. Brian Dumaine is the author of a forthcoming book on Amazon to be published by Scribner. This article originally appeared in the November 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |

-

熱讀文章

-

熱門視頻