這家藥企的一次高調收購,導致美國數百種救命藥品持續短缺

|

露絲·蘭多是紐約哥倫比亞大學醫學中心的婦產科麻醉師。今年2月的一天,她正在查房的時候,接到了藥劑師打來的一通令人不安的電話——藥劑師說,醫院里的丁哌卡因馬上就要用完了。丁哌卡因是一種幾乎每名產婦生產時都會用到的局部麻醉劑,它起效很快,藥效可以預估,一直是該醫院輔助分娩時的不二之選,一般用于自然分娩中的硬膜外麻醉,或是剖腹產時的脊椎麻醉。它通過葡萄糖溶液給藥,在緊急分娩時是一種極其重要的藥品。 “如果胎兒或者產婦情況不好,就必須分秒必爭。”蘭多表示:“目前,確實沒有另一種麻醉劑的安全性和可靠性比得上丁哌卡因,所以大家才都在用它。”如果醫院繼續以目前的消耗速度使用丁哌卡因,那么庫存的丁哌卡因最多三周內就會用完。而據這種藥品的生產廠商輝瑞估計,下一批丁哌卡因估計得到6月才能上市。 作為一名從業20多年的產科麻醉師,蘭多對各種暫時性的藥品短缺早已見怪不怪了,但這么嚴重且事先沒有任何警告的缺貨卻還是第一次。“丁哌卡因我們已經用了幾十年了,我們非常清楚它如何給藥、多長時間起效,閉著眼睛都不會出錯。可是一夜之間,他們卻跟我說,這種藥沒有了。”幾天內,北美地區所有醫院的麻醉師們幾乎都在社交媒體上討論這個問題,很多麻醉師不得不采取了風險較高的替代方案,比如給產婦上全身麻醉。不過北美的產科已經有幾十年不這么做了。 在美國,這種短缺似乎讓人難以理解,因為美國貌似是個在醫療開支上不遺余力的國家,2016年,美國的醫療支出達到了3.3萬億美元,而且美國也是在精準施藥上走在最前面的國家。然而即便美國的醫療體系貌似極為強大,其漏洞卻也有不少,丁哌卡因的短缺也并非孤例,反而是一種“新常態”。比如每家醫院最常用的各種基本注射針劑,或多或少都處于捉襟見肘的狀態。 |

This February Ruth Landau, an obstetric anesthesiologist at ?Columbia University Medical Center in New York City, was making rounds when she got a disturbing call from one of the hospital’s pharmacists. The center was due to run out of bupivacaine, a local anesthetic used in virtually every baby delivery. Fast-acting and predictable, the numbing agent has long been the drug of choice for supporting childbirth, administered as an epidural for women in labor or as a spinal anesthetic for those having a cesarean section. Prepared in a dextrose solution, the syrup-like injection is especially critical in emergency deliveries. “When the baby or mom is not doing well, every minute counts,” says Landau. “There really is no alternative that provides the same safety, reliability, and comfort that we all have using it.” If the hospital staff continued to use the drug at its usual rate, it would blow through the remaining supply in three weeks. The drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, estimated the next delivery of the product would come in June. A 20-year veteran of her field, Landau had seen a variety of drug shortages come and go during her career, but nothing of this magnitude, and never with such little warning: “Suddenly, we’re being told this one drug—the one we’ve been using for decades, that we know best how to give, how fast it kicks in, we can do it with our eyes shut—suddenly, we’re being told we won’t have that drug.” Within days, anesthesiologists at hospitals across North America were conferring about the same problem over social media; many were throwing out short-term fixes that were risky in their own right—putting delivering mothers under general anesthesia, for example. Landau thought the field had moved past such practices decades ago. Such shortages may seem unfathomable in America where, when it comes to health care, we seemingly spare no expense—shelling out $3.3 trillion in 2016—and muse about the promising future of precision medicine. But even in our staggeringly costly and ambitious health care system, the bupivacaine shortage is not an outlier. Rather, it’s the new norm. Increasingly, the low-cost essential medicines that we’ve used for years—a category known as generic sterile injectable drugs, considered the “bread and butter” of hospital care—are in short supply. |

|

根據最近的統計,美國各大醫院短缺的常用藥品有202種,很多都是極為重要的基礎藥品,比如腎上腺素、嗎啡、無菌水等等。在颶風“瑪利亞”襲擊了波多黎各后,美國連生理鹽水的供應量都跌到了警戒線,因為它的主要生產商沒法將產品和包裝從波多黎各運到美國來。另一種藥品碳酸氫鈉主要用于心臟手術或用于腎衰竭患者,該藥品去年也遭遇了嚴重的短缺。(好在碳酸氫鈉可以從澳大利亞進口,多少緩解了一些用藥荒,不過它直到現在仍然處于短缺狀態。)此外,今年嚴重匱乏的還有各種阿片類針劑,它們可以用來控制重傷、手術和晚期病患的疼痛,因此它本應是醫院和臨終關懷機構的常備藥品。 俄亥俄州代頓市的邁阿密山谷醫院是美國一家頂級的創傷治療醫院,但急診室的護士們現在經常拿不到一些急需的藥物。比如由于缺乏一種叫昂丹司瓊的抗惡心藥物,醫護人員只好拿另一種藥品代替,但那種藥品有比較嚴重的負作用,會刺激病人的血管。再比如用于治療心動過速的地爾疏卓,由于這種藥品遲遲得不到補充,醫護人員只好拿另一種叫美托洛爾的藥物來代替,但后者對于一些人并不安全。 “這種情況讓我晚上睡不著覺……稍有不慎,一次急救就會變成一場災難。” ——戴夫·哈洛:馬丁醫療系統公司助理副總裁兼首席藥品官 已經在醫療行業工作38年的凱倫·皮爾森認為:“我們是在開歷史的倒車。”急診醫生蘭迪·馬里奧特表示,每當病人對他手頭上僅有的藥品過敏時,他只得進一步追問他們:你是真的過敏呢,還是只是有點敏感?“這太荒唐了。”他對《財富》表示:“這種對話其實并不罕見:‘你要不就用這種藥物對付一下吧?它雖然負作用很嚴重,但多少能緩解你的痛苦,因為今天我沒有別的藥物能給你了。’” 藥品短缺問題給美國大大小小的醫院都帶來了嚴峻的挑戰。克里弗蘭診所(Cleveland Clinic)的資深藥品短缺問題研究專家克里斯·斯奈德表示,目前的情況已經惡化到了無以復加的地步。作為美國最先進的醫院之一,克里夫蘭診所每天都會遭遇藥品短缺問題。美國藥物安全實踐研究所去年10月的一項調查顯示,藥品短缺使74%的醫療從業者無法為患者提供最推薦的藥物,而且經常會導致延誤治療。路易斯安納州奧克斯納醫療系統(Ochsner Health System)的藥品服務副總裁黛比·西蒙森表示:“能不能找到一種確保能治好病人的藥物,已經成了我們的一大挑戰。” 這些短缺的藥品有一個共同點,它們幾乎都是美國最大的制藥公司輝瑞生產的(輝瑞排在今年《財富》美國500強排行榜的第57名)。輝瑞也是全球最大的針劑類藥品生產商。不過到5月11日,輝瑞有370種產品斷貨或限量供應,輝瑞表示,其中的102種可能要到2019年才會有貨。 美國為什么有這么多種針劑缺貨?答案其實很簡單,美國最大的針劑藥品生產商不生產它們了。 2015年2月初,當輝瑞宣布有意以170億美元收購世界領先的無菌注射藥物生產商赫士睿時,華爾街一片歡呼雀躍。這筆交易達成的非常快,輝瑞CEO伊恩·里德在12月中旬聯系了赫爾睿CEO邁克·鮑爾。在6天后的會面中,里德提出愿意以30%的溢價,也就是每股82美元的價格收購赫士睿。赫士睿公司經過一番討價還價,在1月初將收購價抬到了每股90美元。兩周后,雙方就簽訂了最終的并購協議。 輝瑞公司在新聞通稿中明確表示,希望通過此次并購,盡快主宰通用無菌注射針劑市場。到2020年,該市場的全球銷售額有望達到700億美元。更引人注目的是,赫士睿本身就是生物仿制藥市場的領先玩家。生物仿制藥指的是大分子生物制劑在專利過期后的仿制藥品。近幾十年,這些大分子生物制劑的專利藥品往往貴得令人咂舌,說是天價也不為過,仿制這些大分子生物制劑,要比仿制偉哥這種小分子藥品困難得多。據輝瑞預測,過不了幾年,生物仿制藥市場就會擴張成一個200億美元的大市場。而在2014年,赫士睿在通用注射針劑和生物仿制藥市場的銷售額總共只有30多億美元。 早在這次收購之前,輝瑞CEO里德就想做一筆具有轉型性質的大交易。他的公司在海外坐擁海量現金,當時在可見的未來里,美國對企業稅改革的可能性并不大,因此很多人都認為,里德可能是想收購一家海外商業實體,搞一個當時比較時髦的“反向避稅”,也就是重新注冊到一個低企業稅的國家。為此,輝瑞做了一次倉促的嘗試,在2014年初企圖以1180億美元惡意收購英國制藥商阿斯利康,但此次嘗試最終以失敗告終。兩年后,輝瑞又企圖以1600億美元收購總部位于愛爾蘭的制藥公司艾爾健,但由于美國財政部改革了反向避稅規則,最終輝瑞的這次嘗試也再次告吹。 輝瑞不僅僅對躲避納稅義務感興趣,它還想增長得更大——然后,它的最終目標是變得更小。這些年來,輝瑞曾多次談及拆分成兩個獨立上市實體的想法,其中一個專門搞創新藥物,另一個主要搞非專利藥物、注射針劑、醫療耗材等傳統業務。然而后來輝瑞卻在2016年自行放棄了這個想法,這也讓包括高盛分析師賈米·魯賓在內的很多觀察人士產生了輝瑞缺乏戰略遠見的印象。 魯賓對《財富》表示:“過去三四年,他們都處在比較茫然的階段,他們在財務增長手段基本用完了,增長程度也只是平平。” 至于輝瑞的常用藥業務,其發展軌跡則更為糟糕。這個部門的運營成本比創新藥部門還要高,2017年其銷售額下跌了14億美元,究其原因,應是受赫士睿業務所累。 赫士睿的英文名字“Hospira”是一個生造詞,是由“hospital“(醫院)、“inspire”(靈感)和“spero“(拉丁文的“希望”)三個單詞各截取一部分拼成的。但是近些年來,這家公司確貌似毫無希望可言。它原本是雅培公司生產醫療產品的部門,2004年被剝離成一家單獨的公司。隨著設備日益老化,這家公司基本上是在茍延殘喘地混日子。不過在經濟危機期間,它積極發起了一項旨在提高公司效率的“燃料工程”,2011年一次性裁掉了1400名冗員(三年后補發了6000萬美元的遣散費,但如此大幅的裁員,也影響了公司的產品質量,遣散了很多寶貴的技術工人)。 接下來發生的事情也就自然而然了,2009年至2015年間,該公司收到了8份美國食品藥品監督管理局(FDA)的警告函,并有多批次的產品被召回。該公司的洛基山工廠曾被公司管理層自豪地稱為“王冠上的明珠”,然后FDA的檢查人員卻給這顆“明珠”指出了一連串的問題,比如缺乏適當的測試和控制流程、人員培訓不足、廠房與生產設備設計不佳等等。 2011年,赫士睿迎來了新的管理層。在公司的投資者日上,公司高級運營副總裁吉姆·哈迪對觀眾們說道:“讓我們彼此坦承直言吧,我們都知道,我們有一些問題必須要解決。” 要解決這些問題并不容易。為了解決管理亂象,公司高層專門引進了一支團隊。在他們看來,要想讓洛基山工廠達到合格的水平,至少需要三年時間。有人甚至稱這家工廠是“一場災難”。由于需要測試的產品批次太多,公司只得額外租用倉庫去存放它們。該公司召回的產品數量也越來越多,根據FDA的數據,從2012年到2015年,該公司總共召回了239批次的產品。它的無菌藥劑里發現過各種各樣的雜質,從人的頭發到玻璃渣,再到“橙色不明顆粒物”無所不有。這些召回也給藥品行業刊物增添了不少素材,他們也不遺余力地大肆報道該公司的每一次召回和整治行動。 盡管如此,赫士睿公司還是覺得自己有了些進步。他們引進了人才,整頓了工廠,也緩和了與FDA的關系。CEO邁克·鮑爾本人也經常去FDA開會。在收益電話會議上,鮑爾經常將公司的生產隱患比作“鱷魚”。2014年2月,鮑爾曾表示公司的轉型已經基本成功:“我不能說把所有的‘鱷魚’都抓到了,但是我認為,我們已經把‘沼澤’抽干了。泥漿里可能還潛藏著一兩只,但是我們基本上已經把它們都挖出來了。” 當輝瑞收購赫士睿時,管理層相信一切已經盡在掌控,收拾爛攤子的這支團隊的核心成員也各回各家了。當輝瑞向赫士睿的業務進行投資時,它光在洛基山工廠就裁掉了幾百名員工。 然而一連串的召回并未就此停止。自從2015年9月并購結束以來,至少又發生了45次召回。赫士睿在堪薩斯州的麥克弗森有一家生產了41年的工廠,它與洛基山工廠生產了美國大部分的注射針劑產品,然而政府檢查人員對它的批評卻越來越嚴厲。2016年6月,FDA向該工廠簽發了一封“483”警告函,足足用了21頁的篇幅批評這家工廠,內容包括該廠對投訴不夠重視、沒有開展適當調查,以及產品質量問題等等。 警告函中尤其提到,有醫院投訴某一批次的杜丁胺“在一周后會迅速變成暗粉色”,或是一種“暗沉的香檳色”,有的還會變成“桃紅色”,甚至里面還有“橡皮渣似的屑狀物”。杜丁胺是一種強心劑,當然,它本應該是無色透明的。 麥克弗森工廠坐落于一座老舊的鐵路小鎮邊上,8個月后的2017年2月,該工廠再次收到了FDA的警告函。 這封警告函一共2500余詞,函中提到了方方面面的問題。尤其是函中提到,在某一批次的萬古霉素針劑中發現了不明顆粒物。(經輝瑞公司后來檢測,這種不明顆粒物是硬紙板的碎屑。)雖然投訴不斷,但輝瑞在整整五個月里并未召回大量產品。FDA在警告函的結尾處毫不客氣地給此事定了性:“數個工廠反復出現質量問題,表明你公司對藥品生產的監管和控制是不力的。” 輝瑞公司生產了美國75%的阿片類注射針劑,其中大部分又是在麥克弗森工廠生產的。另外,美國的大量麻醉劑,包括前文中提到的產婦分娩時要用的丁哌卡因,也都是在這里生產的。 在哥倫比亞大學醫療中心,蘭多和她的同事們制定了一些節約措施,好讓有限的丁哌卡因能多用幾個月。丁哌卡因是一種局部麻醉藥品,醫院的各個科室和各種手術都用得到,但根據最新規定,哥大醫院只有風險最高、最復雜的緊急分娩情形才能使用它。而全國范圍內,各大醫院也在紛紛推廣蘭多等人制定的節約措施。比如丁哌卡因原本是一小瓶專供一個病人的,用剩下的就會被處理掉。而現在它在備藥時則會被分成多支針劑,好多給幾個病人用。 供給短缺這四個字聽起來似乎屬于上個時代,又像是一個用來形容社會主義經濟功能失調的名詞,然而事實上,多年來,短缺在美國也一直是一個頑疾。近十年來,美國遭遇的供給短缺不勝枚舉。根據最具權威的猶他大學短缺藥品名錄顯示,2011年,美國最新短缺的藥品達到了創紀錄的257種,與此同時,持續短缺的藥品也達到184種。就此事,美國國會召開了多次聽證會,政府問責局也寫了一系列報告。這些短缺充分暴露了美國醫療系統供應鏈的脆弱,甚至早就已經處于崩潰的邊緣。 最容易出現短缺的藥物都有一些共同點——它們一般是非專利藥品,產量較大,生產利潤很低,對于生產商來說沒什么賺頭,比不上那些對企業盈虧意義重大的先進的專利藥。因此,對于這些我們使用最多但利潤最薄的基礎藥物,逐利的企業自然是沒有太多興趣的。 美國國會在2012年通過立法手段,要求藥品生產商在預見會出現供給短缺問題時,要提前給出更多通知。然而這一解決方案似乎并未抓住重點——重點是市場失靈了,原因可以歸結為缺乏經濟激勵。 對于藥品生產廠商來說,他們從這些被大量使用的廉價藥中賺不到多少利潤,因為它們的藥價主要由廠商和團購組織通過談判商定,這些團購組織存在的意義就是為了讓醫院能拿到低價藥。這樣一來,常用廉價藥就成了一場薄利多銷的游戲,促進了市場固化。另外,制藥行業又是個嚴監管、高成本的市場,被擠出行業的企業也不在少數。同時,這也使企業更不愿意追加投資,或是為供應鏈建立冗余。反正就算供給短缺了,對藥品生產商的經濟影響也是暫時的,而且影響有限。另外由于行業參與者太少,客戶本身也沒什么選擇。結果就是整個體系拿著將將夠用的庫存得過且過,只要不出什么意外,就混一天算一天。 然而去年卻出了不少意外。 |

As of last count, there were 202 medicines on the drug shortage list. They include a bafflingly wide array of medical staples such as epinephrine, morphine, and sterile water. Already in short supply, the nation’s stocks of saline—the saltwater solution used to administer other drugs through IV lines—fell perilously low after Hurricane Maria crippled its main manufacturer’s ability to get product and empty bags out of Puerto Rico. Sodium bicarbonate, another indispensable product—essentially baking soda in solution—that is used in heart surgeries and for kidney-failure patients, was likewise in critical shortage last summer. (Australian imports have helped, but the product remains on the shortage list today.) This year hospitals are struggling to get injectable opiates, which hospitals and hospices use to manage the pain of serious injury, surgery, and terminal disease. In Ohio, at Dayton’s Miami Valley Hospital, a top-tier trauma center, ER nurses can’t get their hands on medicines they’ve used for years. They’re short of ondansetron, a first-line anti-nausea medication, for which they’ve had to substitute another drug that can cause side effects and irritate some patients’ veins. There isn’t any diltiazem, a one-time staple to treat rapid heart rate. (The drug doctors now use instead—metoprolol—isn’t safe for some people.) “This is what keeps me up at night… the situation is an emergency waiting to be a disaster.” ——Dave Harlow: Assistant Vice President and Chief Pharmacy Officer, Martin Health System “We’ve stepped back in time,” says Karen Pearson, who has worked on the ward for 38 years. When patients say they have allergies to the only available drugs, Randy Marriott, an emergency physician, now feels he has to press them: Is this a true allergy or just a sensitivity? “It’s ridiculous,” he tells Fortune. “This is not an infrequent conversation I have. ‘Can I give you this drug that will give you miserable side effects to relieve your pain? Because today I don’t have another drug to give you.’” The problem is testing health care networks, large and small. Chris Snyder, Cleveland Clinic’s seasoned drug shortage specialist, says the situation is as bad as it has ever been; on average, a shortage crops up at the state-of-the-art system every weekday. According to an October survey from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, shortages have prevented 71% of practitioners from providing recommended drugs or treatment and frequently delay care. “Our primary responsibility is taking care of patients,” fumes Debbie Simonson, VP of pharmacy services at Ochsner Health System in Louisiana. “That becomes a challenge when we’re making sure we can get a drug to take care of them.” There’s another thing these drugs have in common, though. They’re almost all produced by America’s largest pharmaceutical company, Pfizer (No. 57 on this year’s Fortune 500). Indeed, as of May 11, the company, which is also the world’s largest maker of sterile injectable drugs, had 370 products that are depleted or in limited supply, 102 of which the company has indicated will not be available until 2019. The simple answer to why America currently has so many shortages of generic sterile injectable drugs: America’s leading manufacturer of generic sterile injectable drugs hasn’t been ?making them. Wall Street cheered when Pfizer announced its intention to buy Hospira, the world’s leading maker of generic sterile injectable drugs, for $17 billion, in early February 2015. The deal had been done after a hasty courtship—Pfizer CEO Ian Read reached out to Hospira chief Mike Ball in mid-December, and at a meeting six days later, Read offered to buy the company at a 30% premium, or $82 per share. By mid-January the Chicago-area Hospira had negotiated it up to $90. Two weeks later the parties had signed a definitive merger agreement. Pfizer’s press release made clear its hopes of soon dominating the generic sterile injectable drugs market, a segment where global sales were projected to reach $70 billion by 2020. Perhaps even more tantalizing, Hospira was a leading player in the fledgling biosimilar market. Biosimilars are essentially generic versions of large-molecule “biologics,” the often phenomenally expensive medicines that have dominated drug development in recent decades. They’re much harder to copy than small-molecule drugs like Viagra. Pfizer forecast that would be a $20 billion market in a handful of years. Hospira’s combined net sales in these two categories in 2014 were just over $3 billion. Pfizer CEO Read had been looking to make a transformative deal. His company was sitting on a pile of cash overseas, and with no corporate tax reform in sight, many suspected Read’s master plan was to buy an overseas entity that would allow the pharma company to, as was fashionable at the time, “invert”—or reincorporate in that lower-tax country. The company made one brash but failed attempt, with a hostile takeover of British drugmaker AstraZeneca, offering to pay $118 billion in early 2014. Two years later Pfizer walked away from a $160 billion deal with Ireland–headquartered Allergan after the Treasury Department changed the rules on tax inversions. Pfizer wasn’t just interested in paring its tax liability. It wanted to get bigger—and then, ultimately, get smaller. The company had long talked of splitting itself into two separately traded units—one that focused on innovative new medicines and the other on medical basics like generics, injectables, and hospital staples. But they backed away from that idea as well in 2016, leaving many observers, including Goldman Sachsanalyst Jami Rubin, with the impression that Pfizer—Big Pharma’s symbolic leader—was strategically at sea. “The last three or four years they’ve been in limbo,” Rubin tells Fortune. “They’ve run out of financial engineering options. Their growth has been pretty flatline.” As for Pfizer’s pharmaceutical staples business, the trajectory has been worse. The division, which is oddly more costly to operate than its drug innovation unit, recorded a $1.4 billion decline in sales in 2017, dragged down primarily by the legacy Hospira business. The name “Hospira” had been cobbled together, according to the company, from the words “hospital,” “inspire,” and “spero,” the Latin word for hope. But for years the business had looked hopeless. Once the hospital products division of Abbott Laboratories, it had been spun off in 2004. With aging facilities, the sterile drugmaker muddled along, and then in the depths of the recession, launched an aggressive efficiency initiative dubbed “Project Fuel.” Fourteen hundred jobs were shed as part of the exercise. According to former employees and a shareholder suit filed in 2011 (and settled three years later for $60 million), the cuts gutted the company’s quality and technical staff. What followed is not terribly surprising: Between 2009 and 2015, the company received eight FDA warning letters and announced a steady drumbeat of recalls. At Rocky Mount, the North Carolina plant that management called the company’s “crown jewel,” FDA inspectors took issue with a comprehensive array of problems, from a lack of proper testing and control procedures to inadequate training of employees to poor design of buildings and manufacturing equipment. By 2011, Hospira had new management, and at the company’s investor day, they offered some straight talk. “Let’s just be real with each other,” senior VP of operations Jim Hardy told the audience. “We understand we have issues to fix.” Fixing them wasn’t easy though. To the team management brought in to clean up the mess, it became clear that getting Rocky Mount alone up to snuff was at least a three-year job. One described the plant as “a disaster.” It had so many batches awaiting testing that the company needed to lease additional warehouse space to store them. Recalls proliferated—the company tallied 239 recalls between 2012 and the start of 2015, according to FDA data—with sterile products already in the marketplace being found to contain everything from human hair to glass to “orange particulate matter.” The saga served as relatively titillating fare for the pharmaceutical trade press, which followed the company’s every recall and disciplinary action with gusto. Still those at Hospira felt they were getting somewhere. They had brought in talent, made improvements to plants, and thawed relations with the FDA; CEO Mike Ballhimself regularly showed up for meetings with the agency. In earnings calls, Ball often referred to the company’s manufacturing woes as “gators,” and when asked by an analyst for a “Gator update” in February 2014, the executive declared something akin to mission accomplished: “I never say never in terms of gators, but I think we’ve got the swamp drained. There might be one or two hiding deep in the mud, but I think we’ve pretty much dug them out.” When Pfizer bought the company, management was confident it had things under control. Key members of Hospira’s cleanup crew were let go. While Pfizer made some investments, it also laid off hundreds of workers at Rocky Mount alone. The string of recalls didn’t stop, however; there have been at least 45 more since the sale went through in September 2015. Hospira’s 41-year-old facility in McPherson, Kans.—which, together with Rocky Mount, produced the bulk of America’s sterile injectable drug supply—drew increasingly harsh reviews from government inspectors. In June 2016 the FDA issued a “483” for the site—a post-inspection memo—that was 21 pages of biting criticism. It chronicled instances of complaints that had been inadequately investigated and product that looked, well, not like you’d want your sterile injectable drugs to look. As to one particular batch of dobutamine, a drug that helps the heart pump blood, hospitals had complained that the medicine, typically clear, “rapidly changed?…?to a dark pink color after a week”—or it was “a dingy champagne color,” or it was “peachy-colored” with “little flakes, like eraser dust.” The McPherson site, which sits at the periphery of an old railroad town, got an FDA warning letter eight months later, in February 2017. The comprehensive 2,500-word document took issue with a gamut of things—and recounted an incident in which the plant received a complaint about particulate matter found in an injection of the antibiotic vancomycin. (Pfizer itself later assessed it to be cardboard.) Despite additional complaints, Pfizer hadn’t recalled the lot of not-so-sterile product for five months. The FDA’s letter ended with a flourish of sweeping condemnation: “Repeated failures at multiple sites demonstrate that your company’s oversight and control over the manufacture of drugs is inadequate.” The McPherson plant is where Pfizer, which makes 75% of America’s injectable opioids, produces most of those drugs. It’s also the production site for a major share of the nation’s anesthetics, including bupivacaine—the drug Columbia anesthesiologist Ruth Landau administers to delivering mothers every day. At Columbia, Landau and her colleagues have established conservation measures to make a limited supply last for months. Though bupivacaine is used as a local anesthetic across the hospital, for all sorts of procedures, Columbia now reserves the dextrose preparation for the most risky and complicated of emergency deliveries. And hospitals nationwide, using guidance Landau helped develop, now prepare multiple doses from a vial that would normally be used on one patient. Shortages may sound like a problem from a bygone era or a dysfunctional facet of socialist economies, but they’ve been a stubborn problem in the U.S. for years. The country experienced a rash of them at the start of the decade. In 2011, a then-record 257 medications were added to the University of Utah’s authoritative shortage list, joining the 184 medicines that were already in short supply. That prompted congressional hearings and a series of reports from the Government Accountability Office. The shortages exposed the fragility of the American health care supply chain, which, as many in the system will tell you, has long been on the verge of buckling. The medications most vulnerable to running short have a few things in common: They are generic, high-volume, and low-margin for their makers—not the cutting-edge specialty drugs that pad pharmaceutical companies’ bottom lines. Companies have little incentive to make the workhorse drugs we use most. Congress’s response was to pass legislation in 2012, requiring manufacturers to give more notice ahead of anticipated shortages—but that seems to miss the point: What we’ve been witnessing, in slow motion, is market failure. It boils down to a lack of economic incentives. Manufacturers of widely used, inexpensive drugs make relatively little off the products, whose prices are largely determined in contract negotiations between drugmakers and group purchasing organizations (or GPOs), which exist to broker better deals for hospitals. That makes this a high-volume, low-cost game, a reality that has driven consolidation in the market. It’s also a highly regulated and somewhat costly industry, which has chased some companies out. The economics make it hard to invest in the business or in building supply chain redundancy. When shortages happen, the financial losses tend to be marginal and temporary; there are too few players for customers to take their business elsewhere. What’s left is a system with just enough inventory to get by if nothing goes wrong. Last year, a lot went wrong. |

|

去年9月,颶風“瑪利亞”嚴重損毀了波多黎各的電網,由此帶來的蝴蝶效應影響了整個美國的醫療系統,它甚至讓我們每個人都處于極其脆弱的境地。美國進口的很多藥物和生理鹽水都是波多黎各生產的。美國衛生與人力資源部應急準備和響應副部長辦公室的一位官員表示:“很多時候,短缺的藥品并沒有理想的替代品,或者很難找到替代品,現在這種短缺的情況越來越多,導致了一連串雪崩似的短缺。”負責統計猶他大學短缺藥品名錄的專家艾琳·福克斯指出,在“瑪利亞”風災之后,先是小袋的生理鹽水開始短缺,隨后大袋生理鹽水以及注射器、藥瓶和無菌水等都開始短缺了。 除了天災,還有輝瑞的“人禍”。 從2017年春天開始,輝瑞時不時就會發布以“親愛的客戶”開頭的信件,無一例外都是提醒客戶可能出現供給短缺——短缺的原因則是麥克弗森工廠出了問題。短缺最嚴重的,是那些需要預裝入注射器的藥品。在長達7個月的時間里,輝瑞只是含糊地表示,公司的生產遭遇了挫折,每封信都表示下批出貨日期要延后。盡管1月到3月,輝瑞關閉了麥克弗森工廠對設施進行升級維修,卻也并沒起到什么效果。 注射麻醉劑的短缺情況也極為嚴重,尤其是輝瑞幾乎控制了整個注射麻醉劑市場。由于阿片類藥物屬于管制藥品,因此它的供給是配額制的,配額由美國禁毒署決定。美國禁毒署每年會根據上年銷量情況,向麻醉劑生產廠商嚴格分配阿片類藥品的原料供給。也就是說,就算其他廠商有能力生產注射麻醉劑,以填補輝瑞留下的大坑,他們也拿不到生產這些麻醉劑的原材料。 2月下旬,包括美國衛生系統藥師協會、美國臨床腫瘤學協會在內的五個醫療組織聯名向美國禁毒署請愿,要求調整配額以解決這一問題。(今年3月,輝瑞自愿放棄了部分配額,美國禁毒署將這些原材料分配給了其他廠家。) 輝瑞公司目前有300多種藥品延遲交付。輝瑞表示,公司非常重視自己的責任,正在想辦法積極解決問題。(在瑪利亞風災之后,輝瑞也加大了部分藥品的產能,以彌補競爭對手的空缺。)不過輝瑞面臨的挑戰是十分巨大的,光是洛基山工廠每年生產的注射針劑就達5億支,每天的產量都能裝滿20輛拖車。那里的工人要同時生產500余種不同的產品,這些藥品有大瓶裝的,有小瓶裝的,也有預裝在注射器里的;既有維生素K,也有抗新生兒凝血的藥品,還有用于臨終關懷的嗎啡等等。 不過該工廠只有26條生產線,也就是說,每天生產線上生產的都可能是完全不同的產品。另外,每一條生產線要想生產某種藥品,都得經過FDA的認證,這個審查過程也相當耗時耗力。要生產某種藥品,必須提前幾周做好排產,當然,某種藥品的生產計劃也可能因為任何不可預見的因素而被取消——比如下大雪、工人生病、零部件未按時到達工廠等等。 如果再算上測試和各種文件手續,一批產品可能需要三到六周才能離開工廠。每一批次的產品在生產環節中都會生成200頁到400頁不等的報告。當然,這些手續也算不上什么技術難題。對于這些需要直接注射到病人血管的藥品來說,如何保持無菌的生產環境,才是最大的挑戰。 |

After Hurricane Maria decimated Puerto Rico’s power grid in September, a cascade of problems for the health system followed—not just on the island, but across the United States. What’s more, it caught everybody off guard. Puerto Rico is home to a significant share of drug manufacturing and much of the nation’s production of saline solution, a central component to hospital care. “More and more, we’re hearing about shortages where there aren’t natural substitutions—or where the identification of substitutions is harder—and that’s leading to cascading shortages,” says an official in the office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the Department of Health and Human Services. Erin Fox, a drug shortage expert who runs the University of Utah’s shortage list, says that after Hurricane Maria when people couldn’t get small bags of saline, there was a run on large bags, then syringes, vials, and sterile water. That natural catastrophe landed in the middle of Pfizer’s man-made one. In spring of 2017, Pfizer began sending “Dear Customer” letters, warning of anticipated product shortages—largely owing to issues at the McPherson facility—every few months. Particularly grave were the issues surrounding syringes prefilled with drugs. Over a seven-month span, the company relayed vague news of additional setbacks in production, with each notification pushing back the arrival of the next shipment. (It didn’t help that the company closed the McPherson plant from January through March to upgrade the facility and make repairs.) Injectable narcotics, in particular, were in desperately short supply—a function of not only the dysfunction at McPherson but also of Pfizer’s near-complete grip on the market. Because these opioids are controlled substances, they are subject to a quota managed by the Drug Enforcement Administration. The agency restricts the amount of the core ingredient that is available each year, and it strictly allocates that supply to manufacturers based on past sales. What this meant was that, even if other companies had the capacity to produce the narcotics and fill the void left by Pfizer, they couldn’t get the raw material to make them. In late February, five medical groups, from the American Society of Health-?System Pharmacists to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, petitioned the DEA to adjust the quota in order to address the problem. (In March, Pfizer surrendered a portion of its allotment, which the DEA reallocated to other suppliers.) Pfizer, whose list of drug back orders is well over 300 items long, says it takes its responsibility seriously and that it’s working feverishly to resolve its supply issues. (After Hurricane Maria, the company also stepped up production of certain drugs to make up for competitors’ shortages.) The challenge is substantial. The Rocky Mount facility, for example, makes up to a half-billion sterile injectables each year, enough to fill 20 semitrailers every day. Workers there make 500 different products, fitted into syringes, vials, and ampoules. They span a human life, from the vitamin K used to prevent blood clotting in new babies to the morphine used to ease the pain of terminal illness. The plant, though, has only 26 manufacturing lines, meaning that any given line is likely to be running something different every day. Each line, moreover, has to be FDA-?qualified for the drugs made on it, a costly and lengthy vetting process. Schedules are typically planned weeks in advance and can be scuttled for any number of unforeseen events, from a snow day to a worker’s illness to components that don’t arrive at the factory on time. Because of the testing and paperwork involved, it takes batches three to six weeks to leave the factory. And each batch generates a 200- to 400-page stack of paper that documents the process. These, of course, are merely logistical wrinkles. Achieving a sterile environment—essential for medicines that are shot directly into the bloodstream—is the true challenge. |

|

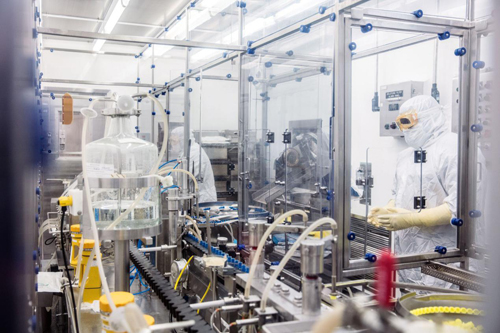

為了不擾亂氣流,在無菌環境中工作的員工一舉一動都要異常緩慢和小心,他們的雙手總是向上舉著,擺出類似投降的姿式。他們周身上下都穿著白色的無菌服,在進入無菌環境工作之前,他們得先花幾個月的時間完全掌握穿脫無菌隔離服的技術。(在上世紀70年代,從事這項工作的工人一般穿著隔離罩衫,戴著一頂紙帽子。)在進入無菌環境前,他們要先進入一個玻璃隔間,對身上穿的隔離服用消毒劑進行滅菌處理。隔著窗子看著他們,感覺有點像在觀摩宇航員登月。工人們埋頭苦干,來自外部世界的需求也從來不會停止。經理們有時候會在生產線上方貼幾張嬰兒的照片,以增加工人的緊迫感和責任感。 輝瑞全球供應總裁兼常務副總裁克里斯汀·倫德-尤根森表示,輝瑞正在盡全力滿足市場需求。“我們不希望再發生嚴重的供給短缺,現在我們的目標非常明確。”輝瑞的經理們現在跟醫院的醫生們差不多,基本上每周都要開會討論藥品短缺情況,然后評估哪些藥品在醫療上是最急需和最重要的,然后優先排產。 對于醫療一線來說,藥品短缺的代價和影響無疑是巨大的。要想給短缺藥品找出足夠的替代藥,藥師們不僅耗時耗力,還得有一定的創造性才行。首先他們得發現哪些藥品和耗材已經短缺了,然后他們要找到幾種替代品,在別的醫院下手前搶先訂購,然后再對現有藥品進行“優化組合”,分派到一線。最后還有一項艱巨的任務,就是如何把這些變化傳達給一線的醫護人員。 在與死神賽跑的急救室,醫生們能不能及時找到替代藥物,能不能正確地使用它們,有時是關乎病人生死的。美國安全藥物實踐研究所收集的大量案例表明,藥品短缺經常會導致醫療事故的發生。2017年一項對300余名醫療業者的調查顯示,在此前6個月的近百起出錯事件中,很多錯誤都是由于醫生將藥品開錯了劑量或濃度而導致的。 |

So as not to disturb the airflow, employees in aseptic spaces move slowly and deliberately, their arms raised as if in an act of surrender. They are fully covered, dressed in white boxy bunny suits that they’re allowed to don only after months of mastering the gowning technique. (In the 1970s, workers suited up for the job in a smock and paper cap.) They are separated from the slightly less sterile areas by windows streaked with disinfectant. Watching workers ploddingly unwrap instruments and tend to their machinery is like watching a lunar landing. In the midst of this logistical labyrinth come the never-ending demands of the world outside. To instill a sense of urgency, managers sometimes post photos of babies above the manufacturing lines. Pfizer is doing its best to meet that demand, says Kirsten Lund-Jurgensen, its president of global supply and an executive VP. “We don’t ever want to have significant supply shortages again,” she says. “The mission is really clear to us.” That means Pfizer managers now have routines much like those of hospital doctors: They huddle every week, she says, to assess the shortages and to prioritize drugs considered “medically necessary” and “medically significant.” Both the costs and effects of these drug droughts, it goes without saying, are also medically significant. Even to cobble together a B-list of drugs and medical supplies requires an inordinate amount of pharmacist hours and some creativity. The goose chase involves calling around for scarce medicines and supplies, identifying multiple alternatives and ordering them before others do, and optimizing available drugs by compounding and repackaging them on site. Then there’s the herculean task of communicating the changes to the hospital staff. And in the melee of ERs, the race to find alternative medications and use them appropriately can sometimes lead to mistakes. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has amassed a great deal of anecdotal evidence that shortages result in medical error. An October 2017 survey of some 300 practitioners revealed nearly 100 instances over the previous six months when mistakes were made—many of them involving administering medicines in incorrect doses or concentrations. |

|

另外,美國醫療系統的防災能力也令人擔憂。佛羅里達州斯圖爾特市馬醫醫療系統助理副總裁兼首席藥品官戴夫·哈羅指出:“今年的颶風季節又快到了,留給我們的時間已經不多了。如果不加以解決,到時急診室將迎來一場災難。”據哈羅統計,他的醫院目前有275種藥品短缺。馬丁醫療系統離特朗普的海湖莊園近在咫尺,然而面對供給短缺,這個總統家門口的醫院也同樣無能為力。 值得一提的是,本文中的多位受訪者(其中并無輝瑞公司的員工)都認為,美國對藥品的質量控制似乎有些矯枉過正,似乎應該稍微給藥廠松松綁了。以前在審查沒有那么嚴格的時候,供應商們總能拿到他們需要的藥品,那時沒有什么自動視覺檢測設備,可是也沒聽說有誰被不合格的藥品治死了。 克里夫蘭門診的藥品短缺問題專家克里斯·斯奈德認為:“大家都想生產出更好的甚至是完美的產品,這種想法可以理解。可是如果醫院無法及時獲得某些藥品,病人的生命就會受到威脅。因此,我們應該有此一問:‘在我們治療病人時沒有藥品了怎么辦?所有其他醫院是怎樣應對這個問題的?’沒有人想看看幕后的深層問題。” 還有人認為,監管上的矯枉過正已經引發了危險的后果。生產無菌藥的工廠被迫停產后(當然,FDA嚴正指出,這并非是他們下達的命令),監管機構相當于將一個不可能完成的任務丟給了醫院——難道要讓他們自己在無菌環境中合成藥物嗎? “所有這些醫院是怎樣應對這個問題的?沒人想看看幕后的深層問題。” ——克里斯·斯奈德:克里夫蘭門診藥品短缺問題專家 在《財富》采訪克里夫蘭門診時,斯奈德表示,他近來一直都在為藥品短缺問題煩惱,有時就連睡覺也會夢到這個問題。基本上他每天都會在地下室里打電話給各個科室的醫生,讓他們檢查重要短缺藥品的庫存。最近他正在焦急地等待一批氯化鉀到貨,據供應商說,這批氯化鉀幾周前就在波多黎各裝船了,預計會在邁阿密卸貨,但不知道為什么,直到現在還沒到貨。“就算船走走停停的,從勞德戴爾堡到尤卡坦半島,開一周也應該到了吧!”斯奈德無奈地對其他藥師道:“我也得去度度假了。” 如果這批氯化鉀再不馬上到貨,藥房工作人員只能改變現有存貨的濃度。這樣一來,IT團隊就得更改整個醫院幾乎所有病人的電子病歷。此話一出,IT團隊傳來一片哀怨之聲。除了氯化鉀之外,這家醫院其他短缺的藥物也有不少。當天斯奈德還得處理一批注射器的召回,據美國疾控中心說,這批注射器可能存在細菌感染。 然而斯奈德對于這種事卻顯得很從容,雖然藥品生產商給他添了這么多麻煩,但他似乎毫無憤怒之意。斯奈德坦承,這種事早已成了他的日常。最后他無奈地說道:“不然我們還有什么選擇呢?”(財富中文網) 本文原載于2018年6月1日刊的《財富》雜志。 譯者:樸成奎 ? |

Another concern is disaster preparedness. “The clock is ticking as we approach hurricane season,” says Dave Harlow, assistant vice president and chief pharmacy officer at Martin Health System in -Stuart, Fla. “The situation is an emer?gency waiting to be a disaster.” Harlow is currently managing 275 shortages. He notes that Martin is within an ambulance-drive range from Mar-a-Lago and that when it comes to the nation’s drug shortages, they don’t discriminate. A number of people interviewed for this story—none who work at Pfizer, notably—suggested that the march of progress in quality control has gone too far, or at least that it should be tempered a bit. Back in a simpler, less scrutinized era, providers got the drugs they needed, and no one seemed to suffer the effects of a drug not passed through automated visual inspection equipment. “In efforts to make better, even potentially perfect products, we may lose sight that being without some of these medications could be life threatening,” says Chris Snyder, the Cleveland Clinic shortage specialist. “We need to ask, ‘What does this look like when we’re taking care of patients? How are all these hospitals dealing with it?’ Nobody wants to look behind that curtain.” Others argue the level of regulatory nitpicking has backfired in a dangerous way. By stalling production at factories that make sterile drugs—and the FDA pointedly denies that it has—the regulator has pushed hospitals into a task many of them aren’t equipped to handle: compounding drugs in a sterile environment. “How are all these hospitals dealing with it? Nobody wants to look behind that curtain” ——Chris Snyder: Drug Shortages Specialist, Cleveland Clinic On Fortune’s visit to the Cleveland Clinic, Snyder channels his laid-back dude. Tall and jolly by nature, the Ohio native says he has been so preoccupied by drug shortages of late that he sometimes dreams about them. On what he calls a typical day, Snyder is in his basement cubicle calling around to colleagues across the system to check on their inventories of essential, short-supply drugs. He is anxiously awaiting a shipment of potassium chloride, which its supplier says was loaded on a boat in Puerto Rico weeks ago, bound, he thought, for Miami. It’s hard to fathom that it hasn’t arrived. “You can get from Fort Lauderdale to the Yucatán peninsula in a week—with stops all along the way,” Snyder quips to the other pharmacists. “I need to go on vacation.” If it doesn’t turn up soon, the pharmacy staff will have to change concentrations of the chemical solution—a step that will force the hospital’s IT team to reconfigure the systemwide electronic medical records. The prospect elicits audible groans from the team. Snyder is also managing other shortages that day, including a mass recall of syringes—the CDC had linked them to bacterial contamination. He seems to take it all in stride, and as he ticks through multiple issues at drug manufacturers, what is most striking is his lack of outrage. Snyder admits it has become business as usual. Then, he asks with resignation, “What choice do we have?” This article originally appeared in the June 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |