《財(cái)富》揭秘:美國(guó)政府囤積了多少比特幣

|

去年7月,25歲的亞歷山大·卡茲在泰國(guó)一家監(jiān)獄自縊身亡,身后留下了堪比頂級(jí)毒販的財(cái)物:別墅、蘭博基尼、保時(shí)捷、列支敦士登和瑞士的銀行賬戶(hù)。官方表示,卡茲是全球最大的毒品和武器黑市網(wǎng)站阿爾法灣(AlphaBay)的運(yùn)營(yíng)者。他還留下了另一樣?xùn)|西:裝有價(jià)值數(shù)百萬(wàn)美元的比特幣及其他虛擬貨幣的電子“錢(qián)包”。 美國(guó)司法部在一次全球突擊行動(dòng)中繳獲了卡茲的虛擬財(cái)產(chǎn),它們現(xiàn)在歸該部所有,司法部計(jì)劃將其出售。比特幣的價(jià)格自繳獲時(shí)到現(xiàn)在,已經(jīng)猛漲了原來(lái)的5倍有余,司法部將獲益豐厚。不過(guò)如果想要知道比特幣的持有者是誰(shuí),或它何時(shí)被交易,必須具備強(qiáng)大的網(wǎng)絡(luò)偵查技能,以及大量的空閑時(shí)間。 數(shù)字貨幣的收繳和銷(xiāo)售,在五年前還鮮為人知,而今正快速成為普通事物。比特幣長(zhǎng)期以來(lái)深受網(wǎng)絡(luò)罪犯喜愛(ài),現(xiàn)在也越來(lái)越多地出現(xiàn)在刑事搜捕案件當(dāng)中,它使得美國(guó)成為了加密貨幣市場(chǎng)的主要參與者。我們無(wú)法得知確切的數(shù)字,不過(guò)根據(jù)書(shū)面證據(jù)和對(duì)現(xiàn)任及前任辯護(hù)律師和檢察官的采訪,可以推算出美國(guó)執(zhí)法部門(mén)至少保管著價(jià)值10億美元的數(shù)字貨幣,并且實(shí)際金額很可能要遠(yuǎn)高于此。 數(shù)字貨幣一旦進(jìn)入政府手中,便蒙上了神秘的面紗。比特幣的匿名性讓它廣受自由論者喜愛(ài),不過(guò)加上這些自由論者所痛恨的不透明的財(cái)產(chǎn)沒(méi)收法律,公眾幾乎不可能追蹤數(shù)字貨幣流向。聯(lián)邦機(jī)構(gòu)為加密貨幣的繁榮發(fā)揮著日趨重要的作用,他們?yōu)槭刈o(hù)手中的數(shù)字黃金做出了令人訝異的舉動(dòng),乃至犯下錯(cuò)誤或者犯罪。 美國(guó)法警局(U.S. Marshals Service)是美國(guó)歷史最為悠久的執(zhí)法部門(mén),槍手懷特·厄普和“狂野比爾”希科克都曾是它的成員。最近,電視和電影作品讓許多美國(guó)人了解到它如何運(yùn)送囚犯及追蹤危險(xiǎn)逃犯,不過(guò)很少有人知道,法警局還出售比特幣。 根據(jù)擁有幾十年歷史的一條法律規(guī)定,法警局這個(gè)隸屬于美國(guó)司法部的機(jī)構(gòu),有一項(xiàng)主要職責(zé)是處理其它聯(lián)邦執(zhí)法機(jī)構(gòu)繳獲的物品,這也是為什么訪問(wèn)法警局網(wǎng)站可以看到被聯(lián)邦調(diào)查局和其他機(jī)構(gòu)收繳的船只、汽車(chē)、飛機(jī)、手表等非法財(cái)物,這些物品全都參加公開(kāi)拍賣(mài)。20世紀(jì)80年代,國(guó)會(huì)的一項(xiàng)決議讓聯(lián)邦官員能更容易地出售毒品犯罪相關(guān)財(cái)物,此后沒(méi)收財(cái)物程序(見(jiàn)邊欄)變得更為普遍,也更具爭(zhēng)議性。 那時(shí),沒(méi)有人知道將來(lái)這些財(cái)產(chǎn)當(dāng)中還會(huì)包括在電腦上挖礦獲得的金錢(qián)。這種認(rèn)知在前幾年對(duì)絲綢之路(Silk Road)的大規(guī)模調(diào)查中就已產(chǎn)生改變。絲綢之路是一家類(lèi)似eBay的全球性非法毒品銷(xiāo)售網(wǎng)站。一位來(lái)自德克薩斯州的年輕人恐怖海盜羅伯茨(真名:羅斯·烏布利希),利用三項(xiàng)當(dāng)時(shí)的新技術(shù)建造了絲綢之路網(wǎng)站。它們分別是廉價(jià)的云數(shù)據(jù)存儲(chǔ);允許用戶(hù)隱秘游覽網(wǎng)絡(luò)世界黑暗深處的洋蔥瀏覽器;以及允許用戶(hù)不通過(guò)銀行,以安全、半匿名方式相互支付的比特幣。 |

When Alexandre Cazes hanged himself in a Thai jail cell in July, the 25-year-old left behind the trappings of a big-league drug dealer: villas, Lamborghinis, a Porsche, bank accounts in Liechtenstein and Switzerland. But Cazes, who authorities allege operated AlphaBay, the world’s largest black-market website for drugs and weapons, also left something else: Internet “wallets” holding millions of dollars’ worth of Bitcoin and other virtual currencies. Cazes’s digital loot is now property of the U.S. Justice Department, which seized it during a global sting operation. The agency plans to sell it, and given that Bitcoin’s value has soared more than fivefold since then, it could reap a huge windfall. But if you want to find out who’s holding those coins, or when they’re being sold, you’ll need extensive cybersleuthing skills—and a lot of free time. These digital seizures and sales, unheard-of five years ago, are fast becoming routine. Bitcoin’s enduring popularity among online wrongdoers, and its growing presence in criminal busts, has turned Uncle Sam into a major player in cryptocurrency markets. While exact figures are impossible to pin down, documentary evidence and interviews with current and former defense attorneys and prosecutors suggest that at least $1 billion worth of digital coins, and possibly much more, has spent time in the custody of U.S. law enforcement. But once in government hands, this digital hoard disappears behind a cloak of secrecy. The anonymity that makes Bitcoin a darling of libertarians—along with opaque property-seizure laws hated by those same libertarians—makes it virtually impossible for the public to follow the digital money. And as federal agencies have been drawn into an ever-growing role in the cryptocurrency boom, their efforts to guard their digital gold have led to surprises, stumbles, and sometimes sin. The U.S. Marshals Service is the oldest law-enforcement agency in the country, counting gunslingers like Wyatt Earp and Wild Bill Hickok among its alumni. More recently, TV and movies have familiarized many Americans with its role transporting prisoners and tracking dangerous fugitives. Far fewer people know the marshals sell Bitcoin. A decades-old law gives the Marshals Service, which is part of the Department of Justice, primary responsibility for disposing of items seized by other federal law-enforcement agencies. That’s why you can visit the marshals’ website and ogle boats, cars, planes, wristwatches, and other ill-gotten gains snatched by the FBI and other agencies, all available at public auction. The seizure process, known as forfeiture (see sidebar), became more commonplace and controversial in the 1980s after Congress made it easier for federal officials to sell assets tied to drug crimes. At the time, no one knew these assets would someday include money mined on computers. That changed earlier this decade during an epic investigation into Silk Road—a global eBay for illegal drugs. A young Texan known as Dread Pirate Roberts (real name: Ross Ulbricht) built Silk Road on three then-new technologies: cheap cloud data storage; the Tor browser, which let people roam dark parts of the Internet undetected; and Bitcoin, which let them pay each other in a secure, semi-anonymous manner, without involving banks. |

|

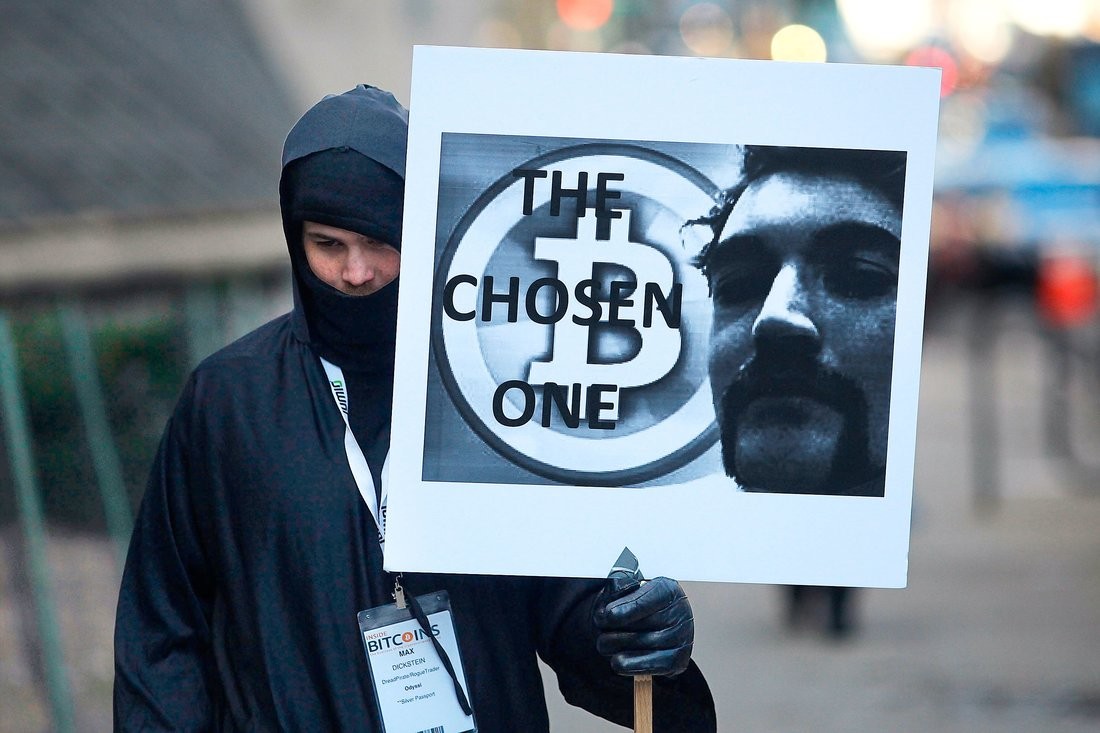

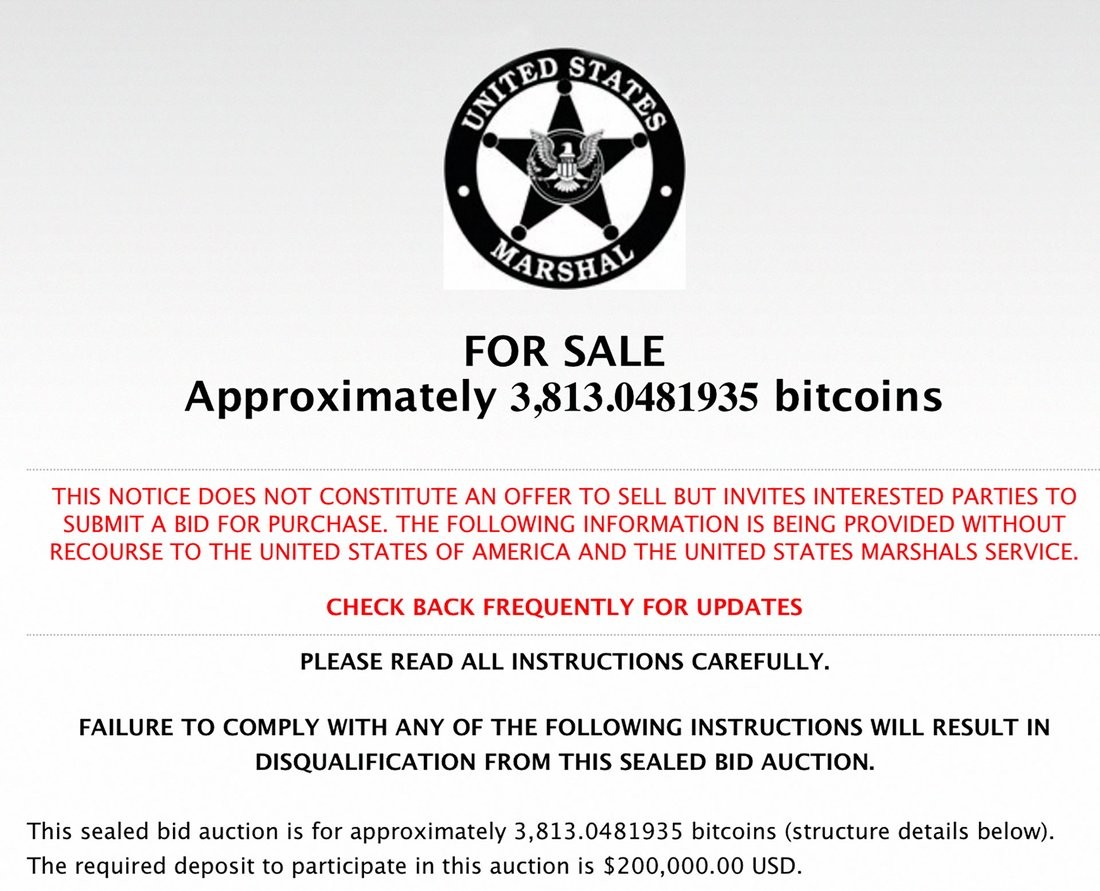

2013年聯(lián)邦政府查封絲綢之路網(wǎng)站時(shí),罪犯?jìng)円呀?jīng)精通比特幣,但執(zhí)法部門(mén)未及時(shí)跟上。參與該案的一位檢察官說(shuō):“對(duì)此沒(méi)有任何專(zhuān)業(yè)知識(shí),它實(shí)在是太新了。”恐怖海盜跟當(dāng)時(shí)(及現(xiàn)在的多數(shù)罪犯)大部分精明的比特幣用戶(hù)一樣,并不依賴(lài)于Coinbase這樣的中介來(lái)持有數(shù)字貨幣。烏布利希利用私人密鑰——一長(zhǎng)串幾乎不可能破解的字符——來(lái)控制他的電子錢(qián)包。執(zhí)法部門(mén)想要獲取設(shè)有私人密鑰的比特幣,唯一的方式就是嫌犯泄露密鑰信息。不甘放棄的特工們想出了在嫌犯貨幣未受保護(hù)時(shí)進(jìn)行繳獲的方法。為得到烏布利希的比特幣,他們?cè)谂f金山圖書(shū)館逮捕他時(shí),當(dāng)他的面奪走他開(kāi)著機(jī)且未上鎖的筆記本電腦。(卡茲一案中,特工們開(kāi)車(chē)迅速進(jìn)入他在泰國(guó)的住處時(shí),他正在使用阿爾法灣的管理員賬號(hào)登陸。)到抓捕恐怖海盜時(shí),法警局的效率已大幅提升。他們控制著至少兩個(gè)自己的電子錢(qián)包,用于存儲(chǔ)絲綢之路的貨幣,接收其他部門(mén)繳獲的比特幣。曾長(zhǎng)期擔(dān)任紐約南區(qū)聯(lián)邦檢察官辦公室資產(chǎn)沒(méi)收部主任,目前為威凱律師事務(wù)所(WilmerHale)合伙人的莎朗·科恩·萊文說(shuō):“這是一項(xiàng)前沿技術(shù),我們從未這樣做過(guò)。”繳獲數(shù)字貨幣之后,法警局回歸常規(guī)程序,將它與可卡因走私販的快艇以同樣方式處置:拍賣(mài)。這是一項(xiàng)挑戰(zhàn)巨大的任務(wù),因?yàn)槔U獲的貨幣數(shù)值巨大,大約有17.5萬(wàn)枚,占當(dāng)時(shí)所有流通比特幣的2%。根據(jù)熟悉案件的檢察官所言,法警局采取了交錯(cuò)拍賣(mài)的方式,以防比特幣價(jià)值暴跌。2014年6月至2015年11月期間舉行的四次拍賣(mài)中,法警局以每枚均價(jià)379美元售出了絲綢之路比特幣。比特幣價(jià)在此后一路飆升。今年1月的另一場(chǎng)拍賣(mài)中,法警局售出3,813枚比特幣,凈賺4,500萬(wàn)美元,每枚比特幣的價(jià)值高達(dá)約1,1800美元。按照這樣的價(jià)格,法警局出售囤積的絲綢之路數(shù)字貨幣本可賺取21億美元,足以支付法警局的年度預(yù)算,但在2014和2015年,它只凈賺了6600萬(wàn)美元。與此同時(shí),身價(jià)億萬(wàn)的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)投資家蒂姆·德雷珀以每枚約600美元的價(jià)格買(mǎi)下了3萬(wàn)枚絲綢之路網(wǎng)站的比特幣,這或許是他這十年來(lái)最佳的投資。德雷珀對(duì)《財(cái)富》雜志說(shuō),拍賣(mài)過(guò)程“十分順利”,而且他一枚也沒(méi)賣(mài)出。他補(bǔ)充道:“為什么我要用過(guò)去交換未來(lái)呢?” |

By 2013, as the feds closed in on Silk Road, criminals had become savvy about Bitcoin, but law enforcement lagged behind. “There was no expertise. It was too new,” says a prosecutor involved in the case. Like most sophisticated Bitcoin users at the time (and most criminals today) the Dread Pirate didn’t rely on a broker such as Coinbase to hold his digital funds. Instead, Ulbricht controlled an online wallet using a private key—a long, complex set of characters that’s basically impossible to guess. In private-key cases, the only way law enforcement can quickly obtain the Bitcoin is if the suspect reveals the key.Enterprising agents figured out ways to snag suspects’ currency when it wasn’t protected. To get Ulbricht’s Bitcoin, they snatched his open, unlocked laptop from under his nose while arresting him in a San Francisco library. (As for Cazes, he was logged in to an AlphaBay administrator’s account when agents rammed a car through the gate of his Thailand estate.) By the time they busted the Dread Pirate, the marshals had got up to speed: They controlled at least two digital wallets of their own, to hold the Silk Road currency and receive Bitcoins seized by other agencies. “This was cutting-edge stuff,” says Sharon Cohen Levin, a longtime chief of the asset-forfeiture unit in the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, and now a partner at WilmerHale. “We’d never done something like this.” Once they did, however, the marshals fell back on standard procedure, preparing to handle the Bitcoin the same way they would a coke smuggler’s speedboat: by auctioning it off. That posed challenges because of the sheer size of the seizure—about 175,000 Bitcoins, or 2% of all the Bitcoin in circulation at the time. According to a prosecutor familiar with the case, the marshals opted for a staggered series of auctions to avoid crashing Bitcoin’s price.In four auctions between June 2014 and November 2015, the marshals sold the Silk Road Bitcoins for an average price of $379. Bitcoin went on to enjoy a huge run-up; as a point of comparison, in an unrelated auction this January, the marshals sold off 3,813 Bitcoins and netted $45 million—or about $11,800 per coin.Sold at those prices, the Silk Road stash could have reaped $2.1 billion, enough to cover the Marshals Service’s annual budget; in 2014 and 2015, it netted just $66 million. Billionaire venture capitalist Tim Draper, meanwhile, made what might be the investment of the decade when he snapped up 30,000 of the Silk Road coins for about $600 each.Draper, who described the auction process to Fortune as “smooth,” says he hasn’t sold a single one, adding, “Why would I trade the future for the past?” |

|

法警局當(dāng)然無(wú)法預(yù)料到這點(diǎn)。前任檢察官、目前在高蓋茨律師事務(wù)所(K&L Gates)工作的克利福德·司特德說(shuō),聯(lián)邦特工出售資產(chǎn)時(shí),不太可能算準(zhǔn)市場(chǎng)時(shí)機(jī)。講及自己曾參與的沒(méi)收證券案件,司特德說(shuō):“我們發(fā)現(xiàn)政府無(wú)意預(yù)測(cè)股市行情。” 絲綢之路比特幣的低價(jià)拍賣(mài)使得聯(lián)邦政府受到加密貨幣愛(ài)好者的嘲諷,而在預(yù)算吃緊的背景下,高價(jià)出售貨幣的壓力驟增。去年11月中旬,比特幣的價(jià)格達(dá)到近2萬(wàn)美元,美國(guó)司法官員迅速找到猶他州的聯(lián)邦法庭,請(qǐng)求允許拍賣(mài)他們從仿冒藥品銷(xiāo)售商手中繳獲的513枚比特幣。法官批準(zhǔn)了該請(qǐng)求,但法警局直到1月末才進(jìn)行拍賣(mài),此時(shí)比特幣已跌至最高價(jià)的一半左右。 地方當(dāng)局也面臨類(lèi)似的棘手問(wèn)題。曼哈頓區(qū)檢察官辦公室網(wǎng)絡(luò)部門(mén)負(fù)責(zé)人布倫達(dá)·費(fèi)舍爾說(shuō):“我們這兒發(fā)生了一起傳統(tǒng)綁架和搶劫案件。罪犯把受害人引誘到他以為是優(yōu)步車(chē)的車(chē)內(nèi),用槍指著他,要他拿出價(jià)值180萬(wàn)美元的[數(shù)字貨幣]以太幣,最終迫使他給出私人密鑰。”地區(qū)檢察官辦公室成功追回資金,卻遇到一個(gè)難題:劫匪將以太幣轉(zhuǎn)換成了比特幣,比特幣的價(jià)值在盜竊案后大幅上漲,由此引發(fā)新的法律問(wèn)題:誰(shuí)該得到這部分盈余呢? 由司法部運(yùn)營(yíng)的網(wǎng)站Forfeiture.gov乍看之下對(duì)監(jiān)督部門(mén)而言可謂是天賜佳物。最近的某個(gè)星期一,主頁(yè)的一份文件詳細(xì)列舉了由多個(gè)部門(mén)沒(méi)收而來(lái)、價(jià)值至少200萬(wàn)美元的數(shù)字貨幣。從中可以看到,緝毒局從新罕布什爾州的一名毒販?zhǔn)种袥](méi)收140枚比特幣,從波士頓的一名毒販?zhǔn)掷餂](méi)收25枚比特幣;海關(guān)和邊境保護(hù)局則在鹽湖城繳獲99枚比特幣和99單位的比特幣現(xiàn)金(另一種貨幣)。 但這種信息透明轉(zhuǎn)瞬即逝。從物品被沒(méi)收直到它出現(xiàn)在報(bào)告里,中間往往有較長(zhǎng)的滯后,而且報(bào)告不會(huì)在線存檔。每天,新報(bào)告一出現(xiàn),舊報(bào)告便消失。紙質(zhì)副本確實(shí)存在,不過(guò)不管任何時(shí)候,無(wú)論在網(wǎng)上或是書(shū)面材料上,都無(wú)法查到聯(lián)邦政府保管加密貨幣的記錄。 曾為客戶(hù)提供沒(méi)收財(cái)物相關(guān)建議的美亞博律師事務(wù)所(Mayer Brown)律師亞歷克斯·拉卡托斯說(shuō):“美國(guó)有一點(diǎn)很奇怪,就是它缺少中央登記。”。他補(bǔ)充道:“不管是聯(lián)邦調(diào)查局還是地方當(dāng)局采取的行動(dòng),我們都不知道被沒(méi)收的財(cái)產(chǎn)有多少。”當(dāng)被問(wèn)及是否有沒(méi)收財(cái)產(chǎn)的公共登記處時(shí),法警局發(fā)言人明確回答說(shuō)沒(méi)有。而且,法律并未規(guī)定政府有義務(wù)創(chuàng)建這樣的登記處。司特德和其他執(zhí)法部門(mén)人員基本都支持這種不透明性,他們辯解道,提高透明度,可能會(huì)向罪犯泄露特工的工作方法,或正在進(jìn)行的調(diào)查。 從理論上來(lái)說(shuō),聯(lián)邦政府手中的任何比特幣都是可以追蹤的,因?yàn)榧用茇泿诺慕灰子谰糜涗浽诠矃^(qū)塊鏈分類(lèi)帳上。雖然司法部文件有時(shí)會(huì)公開(kāi)識(shí)別“安全的政府錢(qián)包”,但許多刑事案件并沒(méi)有,這使得比特幣的去向不明。即便在錢(qián)包可以識(shí)別的情況下,它的內(nèi)容在外行人眼中似乎只是無(wú)窮無(wú)盡的字符串——它們實(shí)際上代表著匿名的個(gè)人貨幣、交易和用戶(hù)。可以肯定的是,包括Elliptic和Chainalytic等取證公司在內(nèi)的行業(yè)正在不斷興起,幫助客戶(hù)將錢(qián)包與所有者聯(lián)系起來(lái),它們的客戶(hù)當(dāng)中許多是執(zhí)法機(jī)構(gòu)。不過(guò),公共信息披露不屬于這些公司的業(yè)務(wù)范圍。 這種狀況導(dǎo)致人們幾乎無(wú)法確定政府到底擁有多少加密貨幣,加之有權(quán)繳獲比特幣的機(jī)構(gòu)眾多(其中還有特勤局、酒精、煙草和火器管理局、郵局),政府本身也難以確定所沒(méi)收加密貨幣的規(guī)模。其實(shí),只要區(qū)塊鏈技術(shù)部署到位,很容易就能知道貨幣數(shù)額,這點(diǎn)令支持提高透明度的人尤為惱怒。沒(méi)收的批評(píng)者認(rèn)為,比特幣黑洞是以數(shù)字化方式展示了被濫用長(zhǎng)達(dá)數(shù)十年的系統(tǒng)。反對(duì)者認(rèn)為,州和地方機(jī)構(gòu)擁有強(qiáng)大的沒(méi)收權(quán)力,會(huì)帶來(lái)負(fù)面作用,甚至可能導(dǎo)致警察搶劫平民。司特德說(shuō):“我在執(zhí)法部門(mén)工作了23年,我相信,但凡警察沒(méi)收現(xiàn)金,總有人從中貪污,我不認(rèn)為這在比特幣身上會(huì)有任何不同。” 從這個(gè)角度看,公共記錄與實(shí)際的差距之大足以令人擔(dān)憂(yōu)。從法庭記錄和沒(méi)收通知中嘗試追蹤比特幣時(shí),《財(cái)富》雜志發(fā)現(xiàn),有幾筆比特幣的繳獲被記錄在案,其銷(xiāo)售卻沒(méi)有任何記錄。例如,2014年的法庭文件顯示,美國(guó)聯(lián)邦稅務(wù)局從德克薩斯州的一位大麻毒販?zhǔn)种欣U獲222枚比特幣,但沒(méi)有任何關(guān)于銷(xiāo)售的文字記錄。同樣,特勤局2014年從一對(duì)在“JumboMonkeyBiscuit”網(wǎng)站經(jīng)營(yíng)非法毒品和貨幣兌換的夫婦手中繳獲50.44枚比特幣,也沒(méi)有拍賣(mài)記錄。(其他一些案例中的貨幣估值也相當(dāng)古怪——例如,2月初鹽湖城繳獲99枚比特幣的沒(méi)收通知中,顯示其價(jià)值為0美元,而實(shí)際上它當(dāng)時(shí)價(jià)值約有80萬(wàn)美元)。這些貨幣中的一部分可能被正在進(jìn)行的案件占用,或還在沒(méi)收機(jī)構(gòu)手中。由于法警局拒絕就內(nèi)部程序發(fā)表評(píng)論,也就無(wú)從得知他們是否有正當(dāng)理由來(lái)解釋這些比特幣的去處。 到目前為止,沒(méi)有證據(jù)表明政府官員利用沒(méi)收程序漏洞來(lái)盜取比特幣,前檢察官(包括司特德)則強(qiáng)調(diào),腐敗是例外,而非全部。盡管如此,沒(méi)收和出售的長(zhǎng)時(shí)間間隔無(wú)疑增加了辯護(hù)律師和公民自由論者的懷疑。所有消息來(lái)源都認(rèn)為,不透明的監(jiān)督加上數(shù)字貨幣容易轉(zhuǎn)移的特點(diǎn),很容易就會(huì)讓執(zhí)法者誤入歧途,聯(lián)邦調(diào)查局的第一次大型比特幣抓捕行動(dòng)證實(shí)了這點(diǎn)。 賈羅德·庫(kù)普曼是美國(guó)稅務(wù)局刑事調(diào)查科的網(wǎng)絡(luò)犯罪主管。稅務(wù)局打擊犯罪部門(mén)有大約2,000名特工——持有徽章和槍支的會(huì)計(jì)師——屬于不斷壯大的加密貨幣專(zhuān)家隊(duì)伍的一部分。庫(kù)普曼說(shuō):“他們是百里挑一的精英。” 這支團(tuán)隊(duì)最著名的一次抓捕行動(dòng)也成為最飽受詬病的一次,原因在于發(fā)生了監(jiān)守自盜。對(duì)絲綢之路進(jìn)行調(diào)查期間,美國(guó)緝毒局的卡爾·福斯和特勤局的肖恩·布里奇斯瘋狂犯罪,就連阿爾·卡彭也會(huì)自愧不如。恐怖海盜羅伯茨被捕之前,他們從主犯和他的網(wǎng)站上偷取比特幣,并向他勒索財(cái)物。這對(duì)狡猾的家伙甚至冒充殺手,偽造殺死告密者的場(chǎng)景,企圖對(duì)烏布利希進(jìn)行再次欺詐。稅務(wù)局偵探成功誘捕福斯和布里奇斯,兩人都在2015年承認(rèn)與此案件有關(guān)的指控。兩位特工的欺詐發(fā)生在烏布利希的資產(chǎn)被沒(méi)收之前,從嚴(yán)格意義上來(lái)講,他們沒(méi)有影響到?jīng)]收程序。即便如此,從這起案件中可以看出,在數(shù)字貨幣符合沒(méi)收相關(guān)法律時(shí),也可能會(huì)滋生不法行為。 法警局是最適合提供沒(méi)收財(cái)產(chǎn)詳細(xì)賬目的機(jī)構(gòu),但它的運(yùn)行本身就不夠透明。去年9月,參議院司法委員會(huì)工作人員完成漫長(zhǎng)的調(diào)查之后,委員會(huì)主席、參議員查克·格拉斯利(來(lái)自愛(ài)荷華州)對(duì)法警局提出猛烈抨擊,指責(zé)他們?yōu)E用沒(méi)收的資金,購(gòu)買(mǎi)諸如“高檔花崗巖臺(tái)面和價(jià)格高昂的定制藝術(shù)品”等額外福利和奢侈品,其中大部分都地安在了休斯頓新建的資產(chǎn)沒(méi)收學(xué)院,這真是再合適不過(guò)了。上述并不算是特大盜竊案件,可它也無(wú)法平息沒(méi)收批評(píng)人士或比特幣擁護(hù)者的怒火。他們中許多人之所以接受比特幣,就是因?yàn)閷?duì)政府的誠(chéng)信缺乏信心。 據(jù)庫(kù)普曼估算,他的稅務(wù)局團(tuán)隊(duì)已經(jīng)幫助繳獲了價(jià)值數(shù)千萬(wàn)乃至數(shù)億美元的虛擬貨幣。這僅僅是來(lái)自一個(gè)機(jī)構(gòu)的數(shù)據(jù),美國(guó)還有十幾個(gè)機(jī)構(gòu)擁有沒(méi)收權(quán)。按照庫(kù)普曼的猜算,我們可以估計(jì)美國(guó)政府在數(shù)字貨幣市場(chǎng)上的影響力。隨著加密貨幣日趨普遍,這一影響勢(shì)必將不斷擴(kuò)大。 尋找非法貨幣的過(guò)程仍將挑戰(zhàn)重重。前網(wǎng)絡(luò)犯罪檢察官、現(xiàn)怡安集團(tuán)顧問(wèn)尤徳·韋勒表示,多年來(lái),壞人們一直在“轉(zhuǎn)向其他沒(méi)有留下同樣數(shù)字痕跡的貨幣。”許多人放棄比特幣,轉(zhuǎn)而使用門(mén)羅幣和零幣等,它們同樣能夠提供安全支付選擇,但幾乎無(wú)法追蹤。取證公司Elliptic首席執(zhí)行官詹姆斯·史密斯表示,越來(lái)越多的網(wǎng)絡(luò)黑市都在發(fā)展一項(xiàng)名為T(mén)umbler的技術(shù),它能將交易記錄打亂,加進(jìn)付款服務(wù)當(dāng)中。這等于是一場(chǎng)無(wú)窮無(wú)盡的虛擬貓和老鼠游戲。如果執(zhí)法人員自身犯罪,他們偷竊的貨幣能更容易地隱藏起來(lái)。 與此同時(shí),數(shù)字貨幣市場(chǎng)仍在繁榮發(fā)展。forfeiture.gov近期發(fā)布報(bào)告稱(chēng),緝毒局在新澤西州繳獲了6枚比特幣,檢察官辦公室在科羅拉多州一位名叫安東·派克的人身上沒(méi)收了27枚比特幣(價(jià)值約33萬(wàn)美元)。據(jù)報(bào)道,在今年2月初一場(chǎng)針對(duì)全球信用卡欺詐集團(tuán)的突擊行動(dòng)中,美國(guó)又凈賺超過(guò)10萬(wàn)枚比特幣。從理論上來(lái)說(shuō),山姆大叔總有一天會(huì)把這些比特幣全部拍賣(mài)。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng)) 本文的另一個(gè)版本刊登于2018年3月份的《財(cái)富》,標(biāo)題為“山姆大叔的比特幣小金庫(kù)”。 譯者:嚴(yán)匡正 |

The marshals couldn’t have anticipated this, of course. And federal agents shouldn’t be expected to time the market when they sell assets, says Clifford Histed, a former prosecutor who now practices at K&L Gates. In cases Histed worked in which securities were seized, he says, “we realized the government doesn’t want to be in the business of guessing the stock market.” Still, the Silk Road fire sale exposed the feds to ridicule from cryptocurrency devotees—and in an era of strained budgets, the pressure to sell high is great. In mid--December, as prices neared $20,000, U.S. attorneys rushed to federal court in Utah for permission to sell 513 Bitcoins they’d seized from a seller of counterfeit pharmaceuticals. The judge agreed, but the marshals didn’t make the sale until late January, by which point the price of Bitcoin had fallen nearly 50% off its high. Local authorities are dealing with comparable headaches. “We had a good, old-fashioned kidnapping and robbery where they put the guy into what he thought was an Uber and then held him at gunpoint for $1.8 million worth of [digital currency] Ethereum,” forcing him to give them his private key, says Brenda Fischer, who leads the cyber unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. The DA’s office recovered the funds but is now coping with a conundrum: The robber converted the Ethereum to Bitcoin, whose price rose significantly after the theft—raising novel legal questions over who should get the surplus windfall. Forfeiture.gov, a website run by the Justice Department, might seem at first like a godsend for watchdogs. On a recent Monday, a document on the home page detailed at least $2 million worth of digital coin forfeitures involving multiple agencies. You could learn that the Drug Enforcement Administration took 140 Bitcoins from a drug dealer in New Hampshire and 25 more from one in Boston, and that Customs and Border Protection seized 99 Bitcoins and 99 units of Bitcoin Cash (a separate currency) in Salt Lake City. But the transparency is fleeting. There are often long lag times between the date of a seizure and its appearance in a report. And reports aren’t archived online: Each day, when a new one appears, the old one goes away. Paper copies exist—but nowhere, online or on paper, is there a tally of the cryptocurrency in federal custody at any given time. “This country is weirdly lacking in central registries,” says Alex Lakatos, an attorney with Mayer Brown who has advised clients on forfeiture. Whether it’s the feds or local authorities doing the seizing, he adds, “we don’t know how much property has been seized.”Asked if there is any public registry of forfeited property, a spokesperson for the marshals replies with a flat no. And there is no law obliging the government to create one. Histed and others in law enforcement generally defend this opacity; more transparency, they argue, could tip off criminals about agents’ methods or ongoing investigations. In theory, any Bitcoin in federal hands can be traced, because cryptocurrency transactions are inscribed forever on a public blockchain ledger. But while Justice Department documents sometimes publicly identify “secure government wallets,” many criminal cases do not, making it unclear where the Bitcoin went. Even in cases in which the wallet is identifiable, its contents appear to a layperson as endless strings of alphabet-soup characters—anonymized representations of individual coins, transactions, and users. To be sure, a cottage industry of forensics firms, including Elliptic and Chainalysis, has sprung up to help clients—many of them law-enforcement agencies—connect wallets to their owners. But public disclosure is not part of their mission. This state of affairs makes it extremely difficult to figure out how much cryptocurrency the government owns—and it’s not clear, given the range of agencies grabbing Bitcoin (which also includes the Secret Service; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms; and the Post Office) that the government itself knows. For advocates of transparency, it’s particularly galling given that blockchain technology, if deployed well, could easily make this clear. And to critics of forfeiture, the Bitcoin black hole is a digital manifestation of a system that has been abused for decades. Foes say that sweeping forfeiture powers at the state and local level create perverse incentives that can lead, in effect, to cops robbing civilians. “I’ve spent 23 years in law enforcement and, unfortunately, I believe as long as police have been seizing cash, some have been skimming it,” says Histed. “I don’t think Bitcoin will prove any different.” Seen in that light, discrepancies and gaps in the public record take on troubling overtones. In tracing a sample of Bitcoins from court records and forfeiture notices, Fortune turned up several instances of coins whose seizure was documented but whose sale was not. Court filings from 2014, for instance, show the IRS seized 222 Bitcoins from a marijuana dealer in Texas, but there is no documentation of its sale.Likewise, there is no auction record for 50.44 Bitcoins seized by the Secret Service in 2014 from a couple who ran an illegal drug and money-changing site under the name “JumboMonkeyBiscuit.” (Other cases reflect odd valuations—for instance, the forfeiture notice for the 99 Bitcoins seized in Salt Lake—worth around $800,000 in early February—lists the value of the currency as $0). Some of these coins could still be tied up in active cases or in the hands of the agencies that seized them. But since the Marshals Service doesn’t comment on its internal processes, there’s no way to know whether there’s a valid reason why they’re in limbo. There is no evidence to date of government agents misusing the forfeiture process to steal Bitcoin, and former prosecutors, including Histed, stress that corruption is the exception, not the rule. Nonetheless, the long gaps between seizure and sale only amplify the suspicions of defense lawyers and civil libertarians. And sources across the spectrum agree that the combination of opaque oversight and easy-to-move digital currencies creates a powerful temptation to go astray. Indeed, the first major federal Bitcoin bust proved as much. Jarod Koopman is the director of Cyber Crime in the Criminal Investigation division of the IRS. The tax agency’s crime-fighting wing has about 2,000 agents—accountants with a badge and a gun—and counts a growing number of cryptocurrency experts in its ranks. “They’re the cream of the crop,” Koopman says. But one of the team’s best-known busts is also its most disturbing, because it involved an inside job. During the Silk Road investigation, two agents—Carl Force of the DEA and Shaun Bridges of the Secret Service—went on a crime spree that would make Al Capone blush. Before Dread Pirate Roberts was arrested, they stole Bitcoin from the kingpin and his website and tried to extort payment from him. The crooked pair even posed as hitmen, staging a fake execution of an informer as part of another scheme to defraud Ulbricht. The IRS sleuths eventually snared Force and Bridges; both pleaded guilty in 2015 to charges related to the case. The agents carried out their scam before Ulbricht’s assets were seized, so they didn’t technically game the forfeiture process. Still, the case points up the potential for murky doings when digital currency meets forfeiture law. The Marshals Service, which is in the best position to provide a detailed accounting of seized property, is operating under something of a cloud itself. In September, after a lengthy investigation by staffers at the Senate Judiciary Committee, chairman Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) blasted the service for using forfeiture funds to pay for perks and luxury items such as “high-end granite countertops and expensive custom artwork,” much of it installed, appropriately enough, at a new Asset Forfeiture Academy in Houston. It wasn’t exactly a superheist, but it does nothing to assuage forfeiture critics or Bitcoin adherents, many of whom embrace the currency precisely because they lack faith in the integrity of governments. Koopman estimates that his IRS squad has helped seize tens or hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of virtual currency. That’s just one agency: Given that nearly a dozen others have forfeiture power, Koopman’s guess offers a sense of how far the government’s reach could extend into the digital coin market. And that reach will only grow as cryptocurrency becomes more commonplace. Finding illicit currency won’t get any less challenging. For years, bad actors have been “moving to other currencies that didn’t leave the same digital bread crumbs,” says Jud Welle, a former cybercrime prosecutor who is now a consultant with Aon. Many have abandoned Bitcoin for coins like Monero and ZCash, which offer the same sort of secure payment options but are all but impossible to trace. And more online black markets now bake so-called tumblers, which scramble transaction records, right into their checkout services, says James Smith, the CEO of forensic firm Elliptic. It adds up to a potentially endless digital cat-and-mouse game. And if law-enforcement agents ever do go rogue, the currency they steal will be that much easier to hide. The digital money, meanwhile, keeps rolling in. Another recent forfeiture.gov list showed a DEA seizure of six Bitcoins in New Jersey, along with 27 Bitcoins (worth approximately $330,000) taken from one Anton Peck by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Colorado. And an early February sting against a global credit card fraud ring reportedly netted the U.S. 100,000 more Bitcoins. In theory, Uncle Sam will be putting all of it up for auction—someday. A version of this article appears in the March 2018 issue of Fortune with the headline “Uncle Sam’s Secret Bitcoin Landfall.” |

-

熱讀文章

-

熱門(mén)視頻