揭秘中國耐力運動帝國

|

16年前,安德魯·梅西克是一位處于上升期的NBA高管,但也早早地出現了中年人的那些毛病。經常出差和長時間的工作讓他體重上升,容易疲勞而且總是背疼。 作為高中競賽運動員和加州大學戴維斯分校英式橄欖球隊員,梅西克此時重新回歸到了運動中。他開始在紐約中央公園進行短程自行車練習,然后逐步增加騎行長度。他自學了競賽性游泳。2005年,他遇到了自己的最愛——鐵人三項。“鐵人”是業余耐力運動員的最高標準,這項運動包括3.8公里游泳、180公里自行車和42.195公里跑步,中間沒有停歇。 隨著梅西克進行訓練,他的體重從最高時的210磅(94.5公斤)降至僅170磅(76.5公斤),長期以來的背疼也得到了緩解。現在,53歲的梅西克已經完成了三次全程鐵人三項,并經常參加短程鐵人三項比賽。最重要的是比賽讓他從情感上得到了滿足,他說:“它滿足了人們的一種基本需求,人們想知道‘我能做到嗎?’” 梅西克目前的工作是勸說另外數百萬人來回答這個問題。2011年,他成為世界鐵人公司首席執行官,這家公司在全球范圍內組織鐵人三項等體育賽事。2015年,中國大型綜合集團萬達傳媒收購了WTC。今年,萬達傳媒又收購了全球最大的馬拉松和半程馬拉松組織機構。作為這些業務的總負責人,梅西克如今面臨著一個巨大挑戰,讓中國不斷增多而且終日坐在辦公桌前的中產階層產生對這些體育項目的需求。 和其他趨于成熟的產業一樣,耐力體育也在中國尋找活力的源泉。咨詢機構IBISWorld的數據顯示,在美國,耐力體育市場的規模接近20億美元(133億元人民幣),但這個市場最大的一塊兒,也就是馬拉松和半程馬拉松已經停止增長。中國的耐力體育市場較小,但已經出現實現初步繁榮的跡象。2015年,在中國田徑協會注冊的馬拉松賽事有134項,去年這個數字增至328項(美國約為1200項)。此外,中國政府也把重心放在了體育和健身產業上,并將此舉作為以消費品和服務為導向的經濟轉型的一部分。同時,所有主要體育項目中的商業機構都希望參與到這股潮流之中。 |

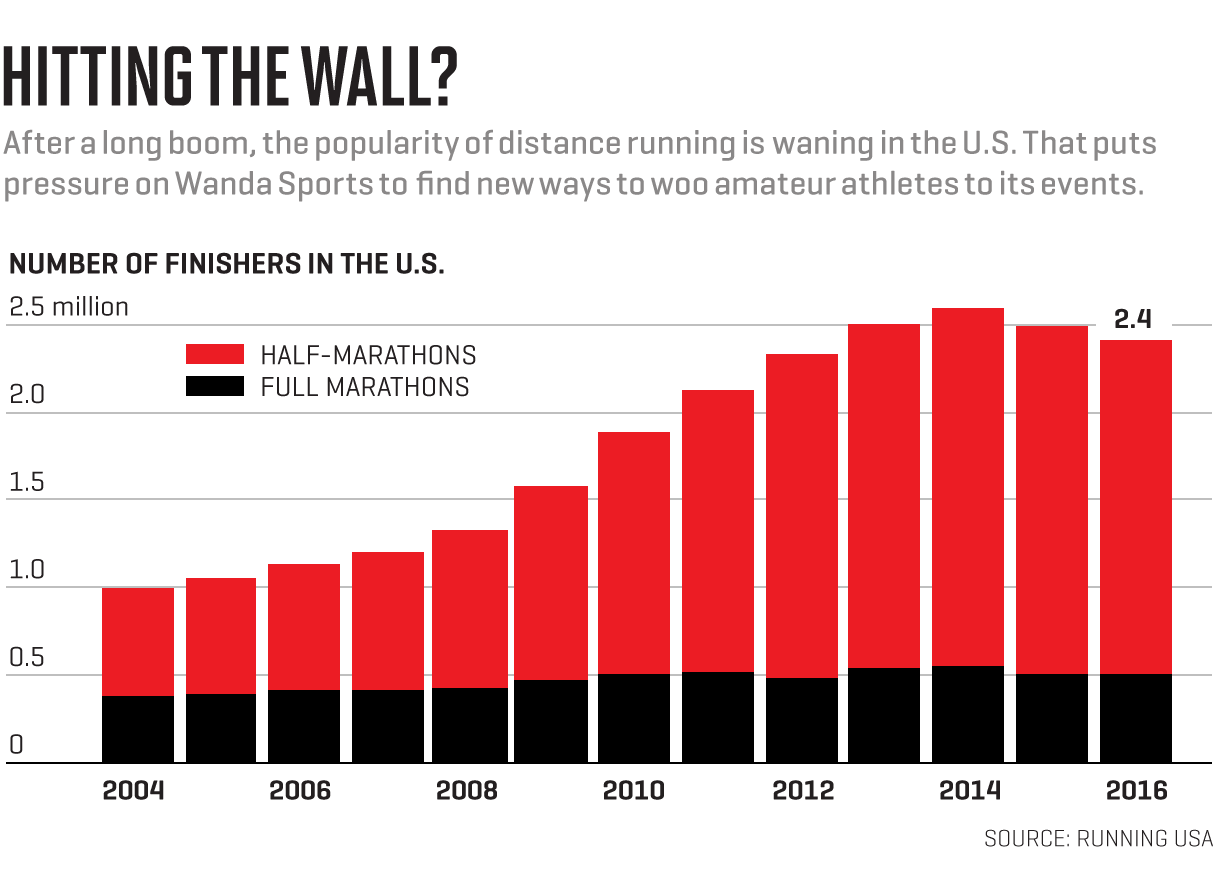

Sixteen years ago, Andrew Messick was an executive on the rise at the National Basketball Association—and suffering from early-onset middle-aged blahs. Constant travel and long hours had led him to pack on the pounds, leaving him easily tired and plagued with back problems. That’s when the former high school track athlete and UC–Davis rugby player rediscovered exercise. He started with short bike rides in New York City’s Central Park, then graduated to longer excursions. He taught himself to swim competitively. And by 2005 he had found his obsession: Ironman triathlons. “Ironmans” are the gold standard for amateur endurance athletes: Each consists of a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride, and a 26.2-mile marathon—with no breaks. As Messick trained, his weight fell as low as 170 pounds from a peak of 210, relieving his long-suffering back. Messick, 53, has now done three full-length Ironmans and competes frequently in shorter triathlons. Above all, he says, competing satisfies him emotionally: “It fills an elemental need in people, which is to know, ‘Can I do it?’?” Today it’s Messick’s job to persuade millions more people to answer that question. In 2011 he became CEO of World Triathlon Corp. (WTC), which organizes Ironman and other sporting events worldwide. In 2015, WTC was acquired by Chinese mega-conglomerate Dalian Wanda, and this year, Wanda bought the world’s largest organizer of marathons and half-marathons. Messick, who oversees the combined operation, now faces an Olympian challenge: generating demand for such events among China’s rising cohort of middle-class, deskbound consumers. Like other maturing industries, endurance sports are looking to China for invigoration. Endurance events are a nearly $2 billion market in the U.S., according to IBISWorld, but its biggest category—marathons and half-marathons—has stopped growing in the States. In China the market is relatively tiny, but there are signs of an incipient boom. In 2015 there were 134 marathon events registered by the China Athletics Association; last year there were 328. (There are about 1,200 in the U.S.) What’s more, China’s government has thrown its weight behind the sports and fitness industries, as part of an effort to reorient its economy around consumer goods and services—a trend that business interests in just about every major sport hope to tap. |

|

億萬富翁王健林的大連萬達集團也希望在這個領域覓得一席之地。萬達斥資約6.50億美元(43.2億元人民幣)從私募股權公司Providence Equity Partners手中收購了WTC。在鐵人三項以外,萬達還將其他幾十種耐力體育項目收入囊中。其中最引人注目的是今年6月對Competitor Group Inc.的收購,后者是搖滾馬拉松的母公司。這項賽事已經進入29個市場,參賽人數達60萬。得益于這些收購,萬達已經悄悄成為全球耐力體育領域的主導企業,它收購的這些公司都成了萬達體育控股的一部分。 萬達體育正開始在中國一試身手。今年中國將舉辦五次鐵人三項比賽,明年將舉辦六次。中國的首屆搖滾馬拉松將于今年10月28日在成都這個有700萬人口的城市舉行,美國聯合航空將成為這次賽事的主贊助商。 |

Dalian Wanda, owned by billionaire Wang ?Jianlin, wants to get in on the ground floor. Wanda bought Ironman for about $650 million from private equity firm Providence Equity Partners. Wanda has also assembled a portfolio of dozens of endurance races outside the Ironman universe. Most notably, in June it scooped up Competitor Group Inc. (CGI), parent company of the Rock ‘n’ Roll marathons, which fields races in 29 markets, with 600,000 participants. Thanks to these acquisitions, now part of Wanda Sports Holding, Wanda has quietly become the dominant global company in endurance sports. The new entity is blazing a trail in China. The country will host five Ironman events this year, and six in 2018. And China’s inaugural Rock ‘n’ Roll marathon and half-marathon will take place Oct. 28 in Chengdu, a city of 7 million, with United Airlines as its major sponsor. |

|

但萬達希望不斷擴張,讓自身業務遠涉海外。萬達體育在全球擁有250多項賽事的主辦權,其收入來自報名費、公司贊助、商品銷售和轉播權。梅西克的設想是讓搖滾馬拉松和鐵人三項相互促進——搖滾馬拉松可以把參賽者導向精英型、成本更高的鐵人三項賽事;WTC則可以和搖滾馬拉松分享其專業能力,后者在資金和組織方面都有困難。信用評級公司穆迪預計,WTC和搖滾馬拉松今年將實現收入3億美元(19.95億元人民幣),并將受益于“明顯的成本協同效應”。如果中國市場的潛力確實像萬達相信的那樣,這個收入數字就有望在10年時間里輕松增長一倍。 但就像馬拉松比賽一樣,個頭大小并不能保證成功。耐力競賽領域正變得越來越擁擠,“最強泥人”等短距離障礙賽一直在奪取市場份額;在資金充裕的理查德·布蘭森資助下,市場新星Virgin Sport也參與到了競爭中,該公司打算推出一系列“節日型”賽事,把瑜伽課和音樂會跟耐力賽事融合在一起。梅西克需要創新,以便讓萬達推出的賽事脫穎而出。他問道:“你怎么才能抓住參賽者的想象力,讓他們有理由在早上4點半起床并參加訓練呢?”回答這個問題需要體力。 |

But Wanda wants to keep expanding far beyond its home country. The combined entity has a roster of more than 250 events globally, from which it earns revenue via entry fees, ?corporate sponsorships, merchandise, and broadcast licenses. Messick envisions Rock ‘n’ Roll and Ironman boosting each other: Rock ‘n’ Roll races can funnel athletes toward the more elite, -expensive Ironmans; WTC, meanwhile, can share expertise with Rock ‘n’ Roll, which has struggled financially and organizationally. ?Credit rating firm Moody’s says it expects WTC and Rock ‘n’ Roll to rake in $300 million this year thanks to “meaningful cost synergies.” If China’s potential is as great as Wanda believes, revenue could easily double in a decade. But just as in marathon running, size doesn’t guarantee success. The endurance-race field has grown increasingly crowded: Shorter obstacle-course events like Tough Mudder have been stealing market share; Virgin Sport, an upstart financed by deep-pocketed Richard Branson, has leaped onto the track with a slate of “festivals” that add yoga classes and concerts to the endurance-race mix. Messick will need to innovate to make Wanda’s offerings stand out. “How do you continue to capture the imagination of athletes and give them a reason to get up at 4:30 in the morning and train?” he asks. Answering that question will take stamina. |

|

作為一項要做出很大個人犧牲的運動,值得注意的一點是搖滾馬拉松的成功源于讓馬拉松變得不那么孤單的努力。這項賽事的靈感出現在1997年,參賽者蒂姆·墨菲在圣迭戈之心馬拉松比賽中突然覺得跑不動了,并且希望能有音樂來推動自己完成最后的幾公里賽程。第二年,他在圣迭戈舉行了首屆搖滾馬拉松。墨菲的想法是把賽跑變成大規模社區聚會,在比賽沿線安排幾十支樂隊,從而給跑者帶來動力,也讓觀賽者得到享受。 跑步愛好者很快就接受了這個概念。舉例來說,每年都有數百人打扮成貓王來參加拉斯維加斯馬拉松。隨著搖滾馬拉松流行起來,組織團隊很快就獲得了幾乎沒有其他舉辦方可以比肩的優勢,那就是用統一的品牌來鼓勵大眾在多個城市參加多項比賽。實際情況證明,這樣的思路對投資公司Falconhead Capital來說不可抗拒。這家公司在2008年收購了搖滾馬拉松所有者Elite Racing,隨后將它和自己的其他業務合并,從而建立了CGI。 |

In a sport associated with intense self-sacrifice, it’s noteworthy that the Rock ‘n’ Roll series’ success sprang from an effort to make marathons less lonely. The theme was inspired in 1997, when runner Tim Murphy found himself hitting the wall during the Heart of San Diego marathon and wishing he had a musical pick-me-up to power him through the final miles. The next year he organized the first Rock ‘n’ Roll race, in San Diego. The idea was to turn races into extended block parties, with a few dozen bands along the route to energize runners and keep onlookers entertained. Runners quickly warmed to the concept: Every year, for example, hundreds dress as Elvis Presley for the Las Vegas marathon. As it caught on, the Rock ‘n’ Roll team soon had an edge few organizers could match: a uniform brand that encouraged large groups to participate in multiple races in multiple cities. That math proved irresistible to investment firm Falconhead Capital, which bought Rock ‘n’ Roll owner Elite Racing in 2008 and merged it with other properties to create CGI. |

|

在新資金支持下,CGI開始大舉收購。它在2008年買下了拉斯維加斯現有馬拉松賽事的主辦權,2009年進入丹佛,隨后涉足國際市場,將業務擴展到了馬德里、愛丁堡、蒙特利爾和里斯本。新的賽事都很成功,CGI也迅速成為這個高度分散、高度本地化的產業中第一家真正的全球性組織機構。同時,贊助商得到了誘人的目標受眾。據CGI介紹,60%的參賽者為女性,家庭收入至少達10萬美元(66.5萬元人民幣)的參賽者占一半。更多大公司加入了贊助行列。據報道,2012年CGI實現收入1.26億美元(8.38億元人民幣),過去五年的銷售額年增幅為26%。 但CGI的核心市場即將遭遇瓶頸。該公司的成長和美國馬拉松賽事的飛速增長同步——2014年完賽人數為55.06萬,比1998年增加63%。但實際情況證明這是個很高的水平,原因是嬰兒潮一代隨著年齡的增長而退出比賽,年輕的運動愛好者則被CrossFit健身和SoulCycle動感單車等存在競爭關系的運動所吸引。行業協會Running USA的數據顯示,2016年參加馬拉松賽事的美國人降至50.76萬(半程馬拉松賽參賽人數也在下降,CGI則是幾項半程馬拉松賽事的舉辦方。)Running USA首席執行官里奇·哈什巴杰說:“繁榮期的增長速度不會持久,[賽事]供給已經超過了需求。” 此前穩健的CGI甚至在這之前就已經變得步履蹣跚。2012年CGI的所有權發生了變更,私募股權公司Calera通過杠桿融資對其實施了收購,導致CGI負債累累。CGI是如此渴望增長,以至于它在首次舉辦比賽時就會召集大量參賽者,而不是以小規模開始,然后逐步成長。2015年,CGI的首屆布魯克林半程馬拉松就吸引了1.75萬名參賽者,但陷入混亂的安檢點和過于擁擠的賽道毀了這次比賽。CGI也變得貪婪起來,甚至在拉斯維加斯的馬拉松賽上出售過移動廁所VIP使用權。梅西克的解讀是,管理層變得更關注投資者的預期,而不是參賽者。 作為一家碰上了市場萎縮而自己又過度擴張的公司,麻煩迎面而來。由于報名人數驟減,CGI不得不砍掉很多比賽,其中包括丹佛馬拉松和普羅維登斯以及圣彼得堡的半程馬拉松。這家資金匱乏的公司再次被貸款人所控制,后者把它轉讓給了萬達,但未披露交易金額。 2008年,Providence Equity以約8500萬美元(5.65億元人民幣)的價格收購了WTC和它的那些鐵人三項賽事,比Falconhead收購搖滾馬拉松晚了幾個月。在兩家被收購的公司中,WTC似乎一直處于落后位置,直到它聘請了梅西克。 在糕點公司Sara Lee和麥肯錫咨詢公司干了一段時間后,梅西克從2000年開始進入了體育行業。作為NBA International高級副總裁,他把NBA的業務擴展到了包括中國在內的海外市場(梅西克隨后進入了賽事推廣機構AEG,后者和NBA在中國建立了合資公司)。梅西克說,他記得最牢的教導來自NBA前總裁大衛·斯特恩和現任總裁蕭華,他們讓梅西克認識到了不偏離品牌內涵的重要性,甚至是在面對擴張壓力的時候。蕭華告訴《財富》雜志:“安德魯覺得如果我們不能按一定的標準來做某件事,那就不應該去做它。” 品牌自律成為梅西克在鐵人三項領域中的核心。2011年,他成為WTC首席執行官。當時WTC授權了幾十項賽事但不負責指導,從而使這項賽事的執行出現了不一致的情況。梅西克收回了這些授權。同時,他迅速進行擴張,通過舉辦更多的70.3鐵人三項賽(也就是半程賽,傳統鐵人三項賽的長度為140.6英里)來擴大這項運動的影響力。他還抓住了銷售商品的機會,比如說,鐵人品牌的天美時手表目前已經成為銷量最大的運動手表。梅西克上任三年后,WTC的收入增長了六倍,達到1.50億美元(9.975億元人民幣)。 梅西克還建立了完善的消費者關系管理數據庫,用于提高消費者的忠誠度。鐵人三項賽事平均參賽人數約為2500人,報名費約700美元(4655元人民幣,而馬拉松比賽報名費接近125美元,也就是831元人民幣)。許多參賽者把鐵人三項視為“比賽一次足矣”的項目,梅西克卻想讓更多愛好者多次參賽。由于愿意參賽的人數較少,這個目標至關重要。梅西克說,消費者關系管理數據庫留住了更多人——在2016年參加過鐵人三項賽的選手中,約41%的人今年還會再參賽一次。 同時,梅西克的職業倫理得到了好評。Providence Equity負責鐵人三項業務的董事總經理戴維斯·諾埃爾說:“他是一位讓部下士氣高漲的領導者,而且熱愛這項運動。”參賽者回報了梅西克的這份熱愛——今年將有約26萬人參加全程和半程鐵人三項賽,幾乎是2011年參賽人數的兩倍。 萬達顯然也很喜歡梅西克。梅西克說,收購WTC以來,萬達基本上讓他自行管理(除了梅西克,萬達未讓其他高層接受采訪)。在萬達集團宏大而又可能讓人困惑的擴張計劃中,萬達體育顯然是一個關鍵組成部分。 萬達集團曾以商業地產為重點,現在則收購了許多完全不同的業務。除了WTC以及馬德里競技足球俱樂部的股份,萬達還擁有傳奇影業和AMC院線的多數股權。在中國,有一批萬達這樣的綜合型集團,有些人認為它們的負債水平已經給中國經濟帶來了系統性風險。今年夏天,萬達迫于政府壓力出售了一些資產。不過,王健林的目標一直都很明確,那就是讓萬達的收入從2016年380億美元(2527億元人民幣)升至2020年的1000億美元(6650億元人民幣),同時到2018年讓娛樂、零售和體育等消費類業務占銷售額的三分之二。 被萬達收購前,CGI就一直在擴展自己的馬拉松版圖。世界馬拉松大滿貫聯盟由六項賽事組成,舉辦地分別為紐約、芝加哥、波士頓、倫敦、柏林和東京,它們吸引著頂尖專業馬拉松選手。今年4月,萬達宣布將和WMM進行為期10年的合作。按照合作協議,萬達將在三年內為WMM增添一項亞洲賽事,而且有可能把WMM帶到非洲。 WMM的賽事標準嚴格而明確,而且無所不包,比如賽道上的水站數量,再比如到機場的距離。但在冠名贊助商制藥公司雅培資助下,WMM希望把參賽者范圍延伸到精英運動員以外。紐約路跑協會主席、紐約馬拉松賽事總監彼得·西亞克西亞說:“雅培兩年前加入進來時,他們就希望更注重大眾參與。” 大眾參與對萬達的收入來說很重要。美式橄欖球或足球等熱門運動的贊助商支付溢價是為了接觸到廣大電視觀眾,和它們的不同點在于,馬拉松贊助商的付費目的是和參賽者及其家庭和朋友這個精英圈子建立聯系。梅西克認為中國可以極大地拓寬這個圈子,他在中國業余選手身上看到了熱切的期盼。舉例來說,2015年參加鐵人三項賽事的中國選手有400名,2016年這個數字增至2800人。 讓西方品牌出現在中國的耐力體育賽事中有合理的商業邏輯。西方奢侈品牌對中國消費者有吸引力,特別是對不熟悉的產品。這是WTC和搖滾馬拉松一直用自己的名字進行運營的原因之一。俄亥俄大學體育管理專業教授、鐵人三項愛好者諾姆·奧賴利說:“萬達可不傻——這些都是投資。他們想要的是有用的品牌。”一個令人鼓舞的跡象是,阿迪達斯去年簽下了一份兩年期合同,將為中國的一些鐵人三項賽事提供贊助,同時正在商討2018年賽事的贊助事宜。 為保持這樣的發展勢頭,萬達需要通過聰明的營銷讓耐力體育更牢固地在中國文化土壤中扎根,同時避免出現萬達接手前搖滾馬拉松賽事的過度擴張問題。 此外,搖滾馬拉松系列賽事需要管理層傾注更多的心血。梅西克說,鑒于65%的參賽者現在都帶著耳機,聽不到沿途樂隊的聲音,舉辦方得重新考慮比賽的形式(一種可能性是向參賽者播放有品牌的曲目,從而獲得收入)。梅西克還需要跟上這項運動的科技競賽腳步。紐約馬拉松冠名贊助商印度的塔塔咨詢服務公司已經開發出一款成熟app,可以實時追蹤參賽者的精確位置。西亞克西亞指出,通過科技來實現社區建設是這項運動接下來要開拓的領域,“跑步的社交性已經遠高于以往任何時候”。 搖滾馬拉松最終可能要把精力集中到它最好的那幾項賽事上,梅西克也暗示,可能會把更多比賽列入“備砍”范圍。他說:“你必須熱愛長跑比賽,但也要為說‘我們救不了它’做好準備。”不過,他相信運動的神秘感會讓這些賽事保持蓬勃生機。在人們看來,馬拉松和鐵人三項都很神秘,幾乎從一開始就是這樣。鐵人三項完賽選手的排名是具有獨占性,以至于許多人都在身上紋了賽事標識。梅西克說:“這些比賽對許多人來說都意味著真正巨大的挑戰。”迎接這項挑戰的選手越多,他的工作就會變得越容易。(財富中文網) 本文將刊登在2017年10月1日出版的《財富》雜志上,題為《創建耐力運動帝國》。 譯者:Charlie 審校:夏林 |

Backed by new capital, CGI went on a shopping spree: It bought existing marathons in Las Vegas in 2008 and Denver in 2009, then went international with acquisitions in Madrid, Edinburgh, Montreal, and Lisbon. It generally turned its new races into successes, and CGI soon became the first truly global organizer in a highly fragmented, localized industry. Sponsors, meanwhile, got a tantalizing target audience: According to CGI, 60% of its runners are women, and half have household income of at least $100,000. More big companies joined its roster, and by 2012, CGI reportedly had revenue of $126 million, with sales up 26% annually over the preceding five years. But CGI’s core market was about to bonk. Its ascent coincided with a meteoric rise in U.S. marathon running: The number of finishers climbed 63% from 1998 to 2014, to 550,600. That proved to be a high-water mark, however, as baby boomers aged out and competing trends like CrossFit and SoulCycle attracted younger athletes. Participation tumbled to 507,600 in 2016, according to Running USA, an industry association. (Half-marathons, of which CGI operates several, also saw a decline.) “Growth during the boom was unsustainable, and supply [of races] was outpacing demand,” says Rich Harshbarger, Running USA’s CEO. Even before then, the formerly sure-footed CGI had begun to stumble. The company changed ownership in a 2012 leveraged buyout by private equity firm Calera that left it with substantial debt. So hungry was CGI for growth that it would drum up huge turnouts for inaugural races, rather than start small and work out the kinks. The company’s first Brooklyn Half Marathon, in 2015, drew 17,500 runners but was marred by logistical snafus such as bag-check chaos and an overcrowded course. The company also got greedy: At one point, CGI sold VIP access to porta-potties at the start area of the Vegas marathon. Messick’s take: Management had become more focused on the expectations of investors than on runners. As an overextended company collided with a contracting market, troubles came to a head. CGI had to ax a number of races, including the marathon in Denver and half-marathons in Providence and St. Petersburg, as registration plummeted. The cash-strapped company ultimately reverted to control of its lenders, who sold it, for an undisclosed sum, to Wanda. Providence Equity bought WTC and the Ironman races for some $85 million in 2008, a few months after Falconhead bought Rock ‘n’ Roll. WTC seemed like the laggard of the two—until it hired Messick. Messick began working in sports in 2000 after stints at Sara Lee and the McKinsey consulting firm. As senior vice president of NBA International, he spearheaded the league’s business expansion into overseas markets, including China. (He later worked for AEG, helping that event promoter build joint ventures with the NBA in China.) Messick says his most memorable mentorships came from former NBA commissioner David Stern and current commissioner Adam Silver; they taught him the importance of not straying from what a brand stands for, even when facing pressure to expand. “Andrew felt if we couldn’t do something to a certain standard, we shouldn’t do it,” Silver tells Fortune. Brand discipline became central to Messick’s approach at Ironman. In 2011, when he became CEO, there were dozens of races that WTC licensed but didn’t supervise, creating inconsistencies in how they were executed; Messick reclaimed those licenses. At the same time he expanded rapidly, widening the brand’s appeal by launching more “70.3” races (triathlons half the length of a traditional, 140.6-mile Ironman). He also pounced on merchandising opportunities; the Ironman-branded Timex, for example, is now a top-selling sports watch. In Messick’s first three years, Ironman’s revenue rose sevenfold, to $150 million. Messick also created a sophisticated customer relationship management (CRM) database to help build customer loyalty. Ironman events average about 2,500 racers, with entry fees around $700 (marathon fees are closer to $125). Many racers treat triathlons as “one and done” achievements, but Messick wanted more athletes to do multiple Ironmans—a crucial goal, given the small pool of people willing to compete. Messick says the CRM system has increased retention: Some 41% of 2016’s Ironman athletes will compete in another event this year. Messick’s work ethic, meanwhile, drew raves. “He’s a leader who inspires the troops and loves the sport,” says Davis Noell, the Providence Equity managing director who oversaw Ironman. And athletes reciprocated that love: About 260,000 people will race in full-length and “70.3” Ironmans this year, almost twice as many as in 2011. Wanda appears to love Messick too: Since it bought WTC, the executive says, the company has largely left him to his own devices. (Wanda declined to make executives other than Messick available for interviews.) But Wanda Sports is clearly a key component in its parent company’s ambitious, if puzzling, expansion. Once focused mostly on commercial real estate, Wanda has been on a buying spree of disparate businesses. In addition to WTC and a stake in soccer’s Club Atlético de Madrid, the company owns film studio Legendary and a majority interest in the AMC theater chain. Wanda is part of a group of Chinese conglomerates that have piled up debt to the point where some view them as posing systemic risk to China’s economy; this summer, under political pressure, Wanda sold off some assets. Still, Wang Jianlin has been clear about his ambitions: Wanda is gunning for $100 billion in revenue in 2020, up from $38 billion in 2016, and wants consumer-facing businesses like entertainment, retail, and sports to account for two-thirds of sales by 2018. Even before Wanda snagged CGI, it was expanding its marathon empire. The World Marathon Majors (WMM) is a grouping of six races that draw top professional racing talent—in New York City, Chicago, Boston, London, Berlin, and Tokyo. In April, Wanda announced a 10-year partnership with the group: The tie-up calls on Wanda to add another Asian race and possibly one in Africa to the roster of Majors within three years. The Majors race criteria are tough and specific: They encompass everything from the number of water stations on a course to the distance to the airport. But under its title sponsor, drugmaker Abbott, the WMM wants to expand its reach beyond elite athletes. “When Abbott joined two years ago, they wanted more focus on mass participation,” says Peter Ciaccia, president of New York Road Runners and race director of the New York City Marathon. Mass participation matters to Wanda’s bottom line: Unlike in major sports like football or soccer, where sponsors pay a premium to reach vast TV audiences, marathon sponsors pay to connect with an elite circle of participants, families, and friends. Messick thinks China can vastly expand that circle; he sees an enormous hunger among Chinese amateur athletes. In 2015, for example, there were 400 Chinese nationals competing in Ironman events. The following year, the number rose to 2,800. There’s also a sound business logic to having Western brands present endurance-sports events in China. Chinese consumers gravitate to Western luxury brands, especially when the product is unfamiliar. That’s one reason Ironman and Rock ‘n’ Roll continue to operate under their own names. “Wanda is not dumb—these are investments,” says Norm O’Reilly, a professor of sports administration at Ohio University and himself an Ironman. “They want brands that are going to work.” In one encouraging sign, Adidas last year signed a two-year deal to sponsor some Ironman races in China and is in talks about 2018 events. To keep that momentum going, Wanda will need savvy marketing to entrench endurance sports more firmly in China’s cultural landscape—while at the same time avoiding the kind of overextension that plagued the Rock ‘n’ Roll series before Wanda bought it. That series, meanwhile, is due for more managerial love. Given that 65% of runners now run with headphones, blocking out bands, Rock ‘n’ Roll has to rethink its approach, Messick says. (One possibility: streaming a branded, revenue-generating playlist to runners.) Messick will also need to keep pace in a tech arms race on the track. India’s Tata Consultancy Services, the title sponsor of the NYC Marathon, has developed a sophisticated app that tracks runners’ exact location in real time. And the use of tech to enable community building is the sport’s next frontier, says Ciaccia: “Running is much more social than it’s ever been.” Rock ‘n’ Roll may ultimately have to focus on its best events, and Messick has hinted that more races could be on the chopping block. “You have to love the races you love but also be prepared to say, we can’t salvage it,” he says. Still, he believes the mystique of exertion will keep the series strong. Marathons and Ironmans are mythical in people’s minds, almost primal. The ranks of Ironman finishers are so exclusive that many get themselves tattooed with the event’s logo. “These races represent a really meaningful challenge for lots of people,” says Messick. The more athletes embrace that challenge, the easier his job will be. A version of this article appears in the Oct. 1, 2017 issue of Fortune with the headline "Racing to Build an Endurance Sports Empire." |